“But there is one thing that I do believe in relation to this problem [of consciousness], and that is that it is a scientific question that eventually should become answerable, no matter how far from being about to answer it we may be at present.” — Roger Penrose

The title above asks if the British mathematical physicist and philosopher of science Roger Penrose (1931-) is a (tacit) panpsychist. Well, he’s certainly not an open panpsychist. Added to that is the fact that he’s rarely — if ever — used the word “panpsychism”. And he certainly hasn’t used that word to describe any of his own theories.

Just to give a quick hint of the main reason why Penrose can’t really be an out-and-out panpsychist.

It’s basically down to his exclusive focus on biological entities. That is, although Penrose offers us the possibility than a single neuron, liver cell or even a paramecium may instantiate some basic form (or level) of consciousness, he never stretches that possibility beyond the biological realm. Indeed his strong scientific, mathematical and philosophical position against the possibility of artificial intelligence makes that crystal clear.

So this essay will conclude that it’s perhaps a little too strong to claim that Penrose’s theories are panpsychist in nature. That said, this issue is complicated; as will be shown later.

In any case, NBC News did once state the following:

“Three decades ago [this was written in 2017], Penrose introduced a key element of panpsychism with his theory that consciousness is rooted in the statistical rules of quantum physics as they apply in the microscopic spaces between neurons in the brain.”

Yet this particular journalist continued by saying that Penrose “does not overtly identify himself as a panpsychist”.

And just as Penrose doesn’t use the word “panpsychism”, so he’s never used (as far as I know) the word “cosmopsychism”. Yet here again is Space.com tying Penrose to this philosophical position:

“Importantly, however, ‘Orch OR suggests there is a connection between the brain’s biomolecular processes and the basic structure of the universe’, according to a statement published in the March 2014 paper ‘Consciousness In The Universe: A Review of the Orch OR Theory’, written by Penrose and Hameroff in the journal Physics of Life Reviews.”

So whatever the case is, Penrose is certainly doing panpsychists at least some favours when he shows them (even if that’s not his aim) that panpsychism can be grounded in at least some kind of science (see opening quote). And that’s even though Penrose’s own science of consciousness is hugely controversial!

Is Roger Penrose a Panpsychist?

Roger Penrose most explicit raising of the possibility of panpsychism (though, again, he never actually uses the word “panpsychism”) can be found in the following passage:

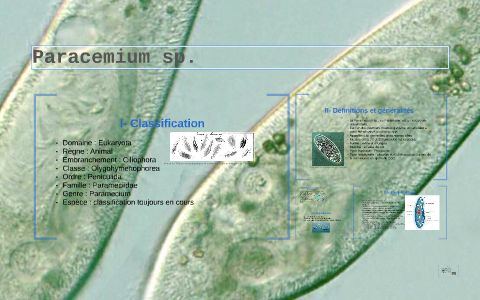

“The question is significantly raised, of course, as to whether a paramecium — or, indeed, an individual human liver cell — might actually possess some rudimentary form of consciousness [].”

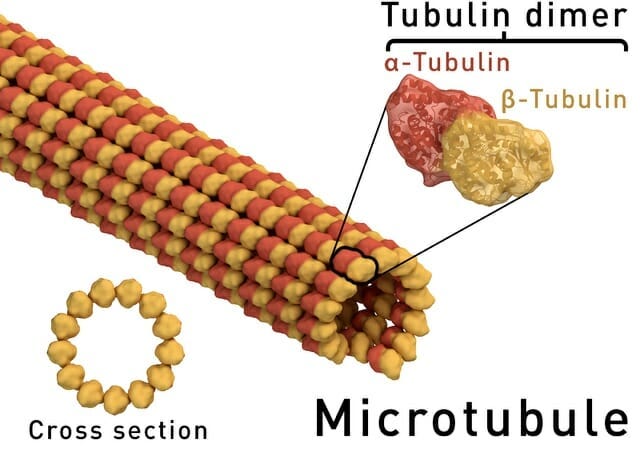

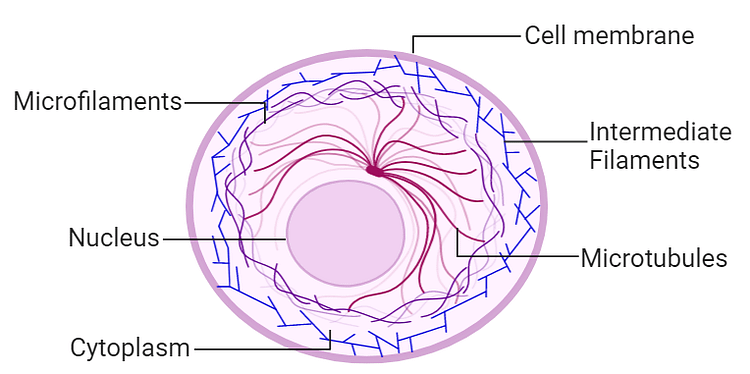

This question is significantly raised because it’s the logical result of Penrose’s own position on consciousness. This position, in basic terms, has it that cytoskeletons and their microtubules are vital when it comes to the “bringing about” (or instantiation) of consciousness. And a paramecium and a human liver cell contain both of these things! In Penrose’s own words:

“I have been making the case that it is to the microtubules in the cytoskeleton, rather than to neurons, that we must look for the place where collective (coherent) quantum effects are most likely to be found.”

And yet

“cytoskeletons are ubiquitous amongst eukaryiotic cells — the kind of cells that constitutes plants and animals”.

Penrose specifically waxes lyrically about the single-celled paramecium when he writes:

“If we are to believe that neurons are the only things that control the sophisticated actions of animals, then the humble paramecium presents us with a profound problem.”

So what is the nature of that problem? Penrose continues:

“For she [a paramecium] swims about her pod with her numerous tiny hairlike legs — the cilia — darting in the direction of bacterial food which she senses using a variety of mechanisms, or retreating at the prospect of danger, ready to swim off in another direction. She can also negotiate obstructions by swimming around them. Moreover, she can apparently even learn from her past experiences [].”

Finally:

“How is all this achieved by an animal without a single neuron or synapse? Indeed, being but a single cell, and not being a neuron herself, she has no place to accommodate such accessories.”

But forget these other creatures! What about the neurons in human brains?

Penrose writes:

“It is the cytoskeleton's role as the cell’s ‘nervous system’ that will have the main importance for us here. For our own neurons are themselves single cells, and each neuron has its own cytoskeleton!”

More relevantly:

“Does this mean that there is a sense in which each individual neuron might itself have something akin to is own ‘personal nervous system’?”

What About Organisation and Complexity?

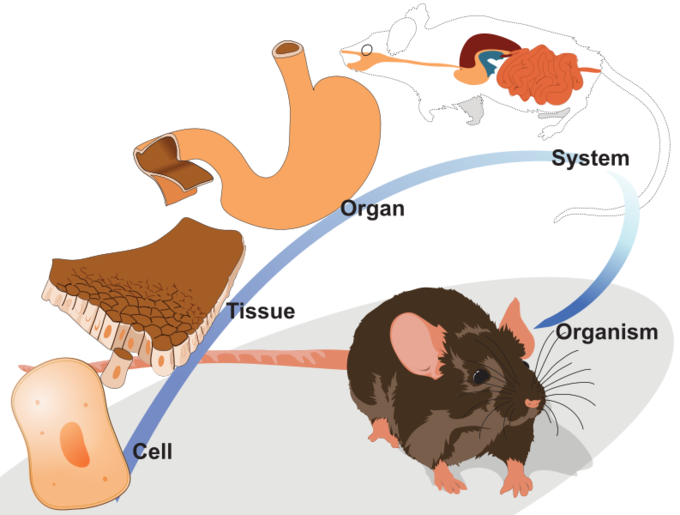

It may — at least at first — seem like a bizarre possibility that a paramecium, liver cell or individual neuron may instantiate a “rudimentary form of consciousness”. However, Penrose does go on to qualify his position when he states the following:

“[I]t must also be the case that the detailed neural organization of the brain is fundamentally involved in governing what form that consciousness must take. Moreover, if that organization were not important, then our livers would evoke as much consciousness as do our brains.”

So Penrose’s basic (if implicit) point is that we should firstly establish what “form” (or level) of consciousness any given entity has (i.e., whether that’s a paramecium, a human liver cell, a single neuron, or an entire human brain). And clearly Penrose is raising the possibility of an extremely basic form of consciousness for a paramecium, liver cell and an individual neuron. Indeed one can even use the technical terms of philosophers here and say that a paramecium, liver cell and an individual neuron may instantiate “proto-experience”, “protophenomenal properties” or “panprotophenomenal properties”.

Yet even though Penrose makes it clear that he’s only talking about extremely basic levels of consciousness here — and even then he’s only raising the possibility of such things — he still concludes with the following words:

“Nevertheless [] what the preceding arguments strongly suggest is that it is not just the neuronal organization of our brains that is important. The cytoskeletal underpinnings of those neurons seem to be essential for consciousness to be present.”

The obvious point to make here is that even if (or even though) the “cytoskeletal underpinnings of those neurons seem to be essential for consciousness to be present”, these underpinnings alone may not bring about consciousness.

So, in basic terms, the following is a simplification of Penrose’s position:

the cytoskeletal underpinnings of neurons + neuronal organisation = consciousness

Indeed we can invert Penrose’s earlier words

“it is not just the neuronal organization of our brains that is important”

with the following statement:

It is not just the cytoskeletal underpinnings of neurons that are important when it comes to consciousness.

Physics and Biology

It will be seen that all Penrose’s examples of the possibility of consciousness (i.e., other than human beings and higher animals) are biological in nature. So that, in itself, won’t be of much help to those panpsychists who believe that consciousness exists all the way down the line from human beings to apes to mice to ants to rocks to particles… and even to spacetime itself. That said and despite the tenor of this essay, Penrose doesn’t see any “essential” reason why non-biological entities can’t be conscious too— at least in principle. Indeed he even argues that

“such (putative) non-computational processes [i.e., in the brain and which Penrose believes are vital for both consciousness and what he calls 'understanding'] would also have to be inherent in the action of inanimate matter, since living human brains are ultimately composed of the same material, satisfying the same physical laws, as are the inanimate objects of the universe”.

Penrose also tells us that he doesn’t “perceive any necessity that such a device [one that instantiates or merely simulates consciousness] be biological in nature”. He goes on:

“I perceive no essential dividing line between biology and physics (or between biology, chemistry, and physics).”

Yet it doesn’t follow that because Penrose doesn’t perceive an “essential” distinction, difference or “dividing line” between biology and physics that he that doesn’t perceive any dividing line at all. And that’s precisely why Penrose immediately carries on with the following words:

“Biological systems indeed tend to have a subtlety of organization that far outstrips even the most sophisticated of our (often very sophisticated) physical creations.”

It must now be stated that Penrose stated all the above in reference to his earlier discussions of artificial intelligence. Yet his words equally apply to the issue of panpsychism too.

Now strictly in terms of AI.

Are Ants Conscious?

Roger Penrose believes that ants are one step ahead of all AI entities. And here again his stress on biology inevitably enters the picture. Penrose claims that the

“actual capabilities of an ant seem to outstrip by far, anything that has been achieved by the standard procedures of AI”.

It’s not clear if Penrose was being careful or if I’m being pedantic here. That is, when Penrose stated the above did he ignore (or dismiss) the ability of AI entities (or even basic computers) to do advanced mathematical calculations, win people at chess, read fingerprints, etc? As far as I know, there aren’t many ants that are good at chess, mathematical calculations, etc. It can be supposed, then, that this may boil down to what Penrose means firstly by the the words “actual capabilities” (i.e., of an ant) and by the the words “standard procedures” (i.e., of AI).

In any case, many AI theorists and champions of AI have pointed out that most of the critics of AI tend to artfully select those things which humans and other animals can do and which AI entities or computers can’t do. Yet of course this approach can be turned on its head by stressing the things that AI entities can do but which humans and other animals can’t do. So, in both these cases, this approach may not be very helpful and may simply amount to mindless point-scoring.

But let’s move on.

Penrose also implicitly ties his ants-vs-AI argument to panpsychism — at least via the issue (again) of microtubules. Penrose continues:

“One might well wonder how much an ant gains from its enormous array of nano-level ‘microtubular information processors’, as opposed to what it could do if it had only ‘neuron-type switches’. As for a paramecium, there is no case to answer.”

So, on a (partly) sarcastic note, this question can now be asked:

How much microtubular quantum stuff must an ant — or anything else — have (or instantiate) in order to actually be conscious?

Now it can be wondered if the supposed “measure” of consciousness (i.e., phi or Φ) in integrated information theory (IIT) may be of help here. Indeed, as Penrose himself hints, even a humble single-celled paramecium may have enough microtubular quantum stuff to bring about — or instantiate — its own consciousness.

Having said all that, Penrose then deflates his tacit panpsychism when he says that he has “always had difficulties in believing that insects have much or any of this quality [of consciousness]”.

To complicate matters even more, Penrose goes straight ahead and qualifies these “difficulties” by tying ants yet closer to a possible panpsychist position — at least at it must be tied to microtubules, etc. Penrose writes:

“Nevertheless [] the behaviour pattern of an ant is enormously complex and subtle. Need we believe that their wonderfully effective control systems are unaided by whatever principle it is that give us our own qualities of understanding?”

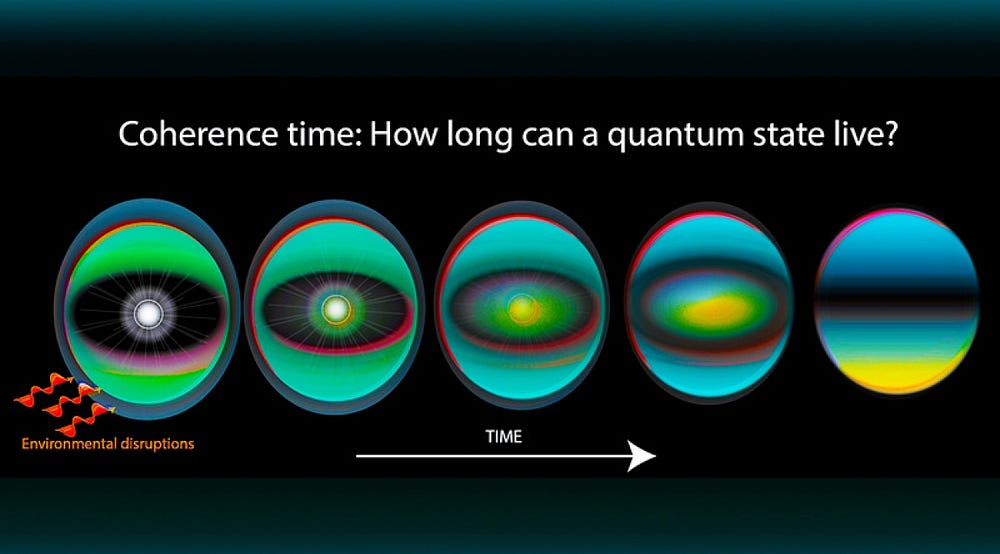

Quantum Stuff (e.g., Coherence)

Penrose expresses his prime motivation for stressing the importance of cytoskeletons and microtubules when he states that

“without such quantum coherence we shall not find a sufficient role for the new OR [Orchestrated objective reduction] physics that must provide the noncomputational prerequisite for the encompassing of the phenomenon of consciousness within scientific terms”.

Penrose then cites the biological and technical reasons why he takes this position. He continues:

“Their controlling neuronal cells have their own cytoskeletons, and if these cytoskeletons contain microtubules that are capable of sustaining the quantum-coherent states that I am suggesting are, at root, necessary for our own awareness, then might they not also be beneficiaries of this elusive quality?”

Moreover:

“If the microtubules in our brains do posses the enormous sophistication needed for the maintaining of collective quantum-coherent activity, then it is difficult to see how natural selection could have evolved this facility just for us and (some of) our multicellular cousins.”

Then, almost like a good panpsychist, Penrose goes all the way down the line by finishing off with the claim that these

“quantum-coherent states must also have been valuable structures to the early eukaryotic one-celled animals, although it is quite possible that the value to them may have been very different from what it is to us”.

Conclusion

In the end, then, it may be unclear if Penrose is a panpsychist — even a tacit panpsychist. His stress on biology certainly puts him at odds with most — or even all — panpsychists. Indeed one can argue that the whole point of panpsychism is that it downplays biology; and, in the process, seemingly gets rid of such problems as strong emergence.

The other thing is that Penrose only discusses the possibility of consciousness in these rudimentary biological entities. This isn’t odd because, as a theoretical physicist, he’s always discussing all sorts of other possibilities too. (Usually possibilities which are worlds away from the issue of panpsychism.) In fact he’s doing what all good philosophers should do — give (most/some of!) these possibilities the benefit of the doubt… at least at first.

On the other hand, it seems that most panpsychists have somewhat smoothly and easily moved from the possibility of consciousness in rudimentary entities to their actually being conscious. (There are various philosophers — such as David Lewis, David Chalmers, Philip Goff, etc. — whose entire philosophies seem to be based on the reality of possibilities.) And most panpsychists have found it easy to move from possibility to actuality because they’ve almost completely divorced their panpsychism from science. (Scientific terms and issues are — of course — brought up by panpsychists; though often in a very superficial way and usually to give panpsychism a little scientific kudos.) Thus the move from the possibility to the actual truth of panpsychism has been easy for such panpsychists.

All this (as it were) turning-the-(merely)possible-concrete is something Penrose himself would have a serious problem with.

And that’s why I believe he probably isn’t a panpsychist.