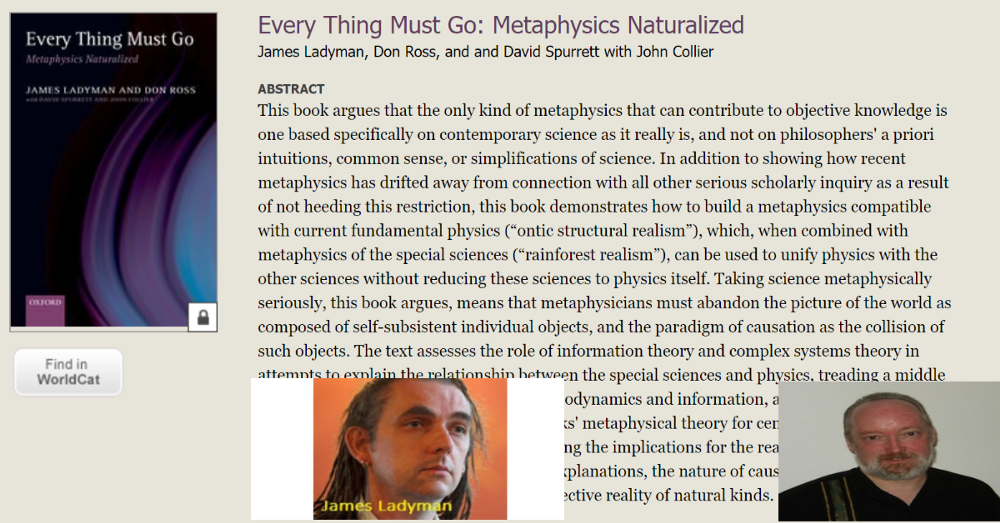

One Pythagorean position on physics is summed up by the ontic structural realists James Ladyman and Don Ross: “Mathematical entities such as sets and other structures are part of the physical world and not therefore mysterious abstract objects.”

This essay is primarily a commentary on the ‘Ontic Structural Realism and the Philosophy of Physics’ chapter of James Ladyman and Don Ross’s book Every Thing Must Go: Metaphysics Naturalized.

********************************

The ontic structural realist philosophers James Ladyman and Don Ross have been classed — variously — as “neo-Pythagoreans” and “Platonists”.

If a philosopher were a neo-Pythagorean (i.e., rather than a Platonist), then such a philosopher may think that (to use Ladyman and Ross’s words)

“mathematical entities such as sets and other structures are part of the physical world and not therefore mysterious abstract objects”.

At least this position “suggest[s] a kind of Pythagoreanism” to Ladyman and Ross.

It must be said here that — on my reading at least — the fusing of mathematical entities with the physical world isn’t really Platonist. It’s not Platonist because Plato’s prime concern was the abstract and atemporal realm of numbers and other abstract objects (such as Forms, Ideas or universals); not abstract objects as they’re instantiated in the physical world.

What does sound very much like Ladyman and Ross’s position (as well as being partially Pythagorean) is the suggestion of

“abandoning the distinction between the abstract structures employed in models and the concrete structures that are the objects of physics”.

Ladyman and Ross go on to say that such “abstract structures employed in models” actually are the “objects of physics” (i.e., if such a distinction is indeed abandoned). In Ladyman and Ross’s case, we can say that abstract structures are the things of physics. In other words, the argument is that if we erase abstract structures from the picture of physics, then we have nothing left…

However, does it follow that abstract structures are literally everything in physics?

Ladyman and Ross quote the Dutch philosopher Bas van Fraassen who stated that

“it is often not at all obvious whether a theoretical term refers to a concrete entity or a mathematical entity”.

Bas van Fraassen’s position would be agreed upon by many actual physicists — or at least by many quantum physicists. (One can read many physicists stating more or less the same thing as Bas van Fraassen.)

Ladyman and Ross then express a position which one would imagine critics have aimed at their own position. They argue that

“the fact that we only know the entities of physics in mathematical terms need not mean that they are actually mathematical entities”.

Now are Ladyman and Ross endorsing that position or simply stating that, as a matter of logic, the following argument is invalid? -

i) If we only know the entities of physics in mathematical terms,

ii) then the entities of physics must themselves be mathematical entities.

Ladyman and Ross go on to explain their position in terms of rejecting what they call the “abstract/concrete distinction”. They argue that

“the dependence of physics on ideal entities (such as point masses and frictionless planes) and models also offers another argument against attaching any significance to the abstract/concrete distinction”.

We still need an answer to whether or not (in Ladyman and Ross’s words) “the fact that we only know the entities of physics in mathematical terms” leads to the conclusion that such entities “actually [are] mathematical entities”. Yes, it needn’t lead to that conclusion. However, to Ladyman and Ross, it does lead to that conclusion.

Isn’t it the case that if there were only mathematical models or mathematical structures, then we couldn’t call them “mathematical models” or “mathematical structures” in the first place? Surely such words exist precisely because of the abstract/concrete distinction. This isn’t necessarily to say that we should attach too much significance to that distinction; or even that we can know the entities of physics without abstract mathematical structures and models. Nonetheless, none of this (in itself) is a reason to reject the abstract/concrete distinction or even to refuse to (in Ladyman and Ross’s words) “attach any significance to” it.

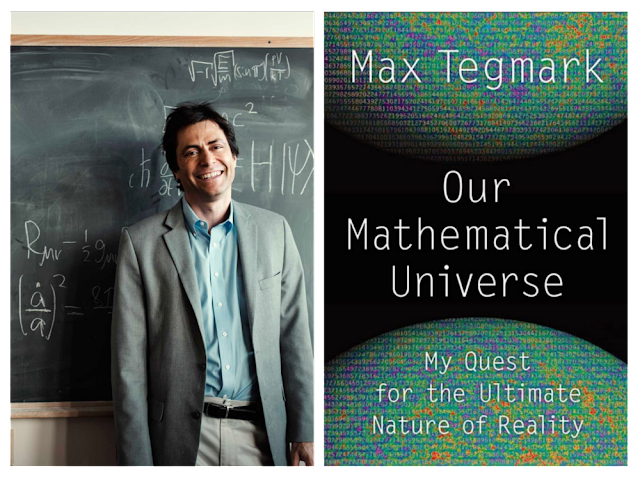

Take the case of a very-explicit Pythagorean: Max Tegmark.

Max Tegmark

To sum up Max Tegmark's position:

i) Because the models of causal processes are identical to those processes,

ii) then they must be one and the same thing.

More precisely, Tegmark’s argument is as follows:

i) If a mathematical structure is identical (or “equivalent”) to the physical structure it “models”,

ii) then the mathematical structure and the physical structure must be one and the same thing.

So, if that’s the case (i.e., that structure x and structure y are identical), then it makes little sense to say that x “models” (or is “isomorphic with”) y. That is, x can’t model y if x and y are one and the same thing in the first place.

Tegmark also applies what he deems to be true about the identity of two mathematical structures to the identity of a mathematical structure and a physical structure. He offers us an explicit example of this:

electric-field strength = a mathematical structure

In Tegmark’s own words:

“‘ [If] [t]his electricity-field strength here in physical space corresponds to this number in the mathematical structure for example, then our external physical reality meets the definition of being a mathematical structure — indeed, that same mathematical structure.”

But here’s an argument and a question:

i) If x (a mathematical structure) and y (a physical structure) are one and the same thing,

ii) then one needs to know how they can have any kind of relation at all to one another. [Gottlob Frege’s “Evening Star” and “Morning Star” story may work here.]

In terms of Leibniz’s law, everything true of x must also be true of y.

But can we observe, taste, kick, etc. mathematical structures?…

Yes we can! But only if we deem physical things to be identical to mathematical structures!

In addition, can’t two structures be identical and yet somehow separate (i.e., not numerically identical)? Well, not according to Leibniz.

All this is perhaps easier to accept when it comes to mathematical structures being compared to other mathematical structures (rather than to something physical): not when it comes to mathematical structures being compared to things. Yet if things are mathematical structures, then even that qualification won’t be accepted by either Pythagoreans or by ontic structural realists.

All this is also expressed (at least as it is applicable at the quantum scale) in the following passage written by the science writer John Horgan (1953-):

“[M]athematics helps physicists define what is otherwise undefinable. A quark is a purely mathematical construct. It has no meaning apart from its mathematical definition. The properties of quarks — charm, colour, strangeness — are mathematical properties that have no analogue in the macroscopic world we inhabit.”

This means that if mathematics is all we’ve got, then it’s not really a surprise that many physicists (i.e., the more philosophical ones) argue that everything important — or even relevant — that’s said about the quantum world is said by the maths.

Structures: Relations and Relata

A realist about things can happily accept that mathematical structures are

“used for the representation of physical structure and relations, and this kind of representation is ineliminable and irreducible in science”

and still be a realist about things (or events/conditions/states/etc.). However, it’s precisely because of the ineliminable nature of mathematical structures in physics that has led ontic structural realists to become eliminativists about things (i.e., they see things as structures too — see here); just as it led Plato and Pythagoras to similar conclusions.

Indeed we can even accept that it’s an important fact that the (as mathematical structuralists put it) “world instantiat[es] mathematical structure” and still believe that the abstract/concrete distinction is important.

For example, the coffee cup and carrot in front of me instantiate mathematical structure. However, they also exist qua coffee cup and qua carrot. There’s also the fact that all objects, events — all things! — exhibit (or instantiate) mathematical structure. That, however, is (in a strong sense) a banal fact because all it amounts to is the fact that every thing can be given a mathematical description and also be mathematically — or otherwise — modelled (i.e., even a coffee cup or a carrot).

Ladyman and Ross also provide a useful set of four positions which focuses on the nature of relations and relata (or things). Thus:

(1) There are only relations and no relata.

(2) There are structures in which things are primary, and relations are secondary.

(3) There are structures in which relations are primary, while things are secondary.

(4) There are things such that any relations between them are only apparent.

At first glance one would take ontic structural realism to endorse (1) or (3). However, since things are themselves structures (according to Ladyman and Ross), then we must settle for (1) above (i.e., “There are only relations and no relata”).

Looking at (1) to (4) again, can’t it be said that (2) and (3) amount to the same thing? In other words, can we distinguish

(2) There are structures in which the things are primary, and relations are secondary.

from

(3) There are structures in which relations are primary, while things are secondary.

at all? Isn’t that a difference which doesn’t make a difference?

So one can still ask — in the metaphysical pictures of (2) and (3) — the following question:

Can things exist without relations and can relations exist without things?

That’s a question of existence.

Now what about natures?

One can now ask:

Can things have their natures without their relations and can relations have their natures without things?

As already stated, Ladyman and Ross adopt option (1) above: There are only relations and no relata.

Universals

Ladyman and Ross give a very interesting Platonist reason as to why they adopt (1) above. They cite as an example this assertion:

“The Earth is bigger than the moon.”

In terms of relata, it’s certainly true that the Earth and the moon exist. It’s also true that the Earth is bigger than the moon.

So what about the relation bigger than?

Here (just as in Bertrand Russell’s ‘The World of Universals’) the metaphysical (well) things called universals come to the rescue. Ladyman and Ross state that the

“best sense that can be made of the idea of a relation without relata is the idea of a universal”.

Thus the relation BIGGER THAN is a universal. (Ladyman and Ross also see it as being “formal”.) That is,

“when we refer to the relation referred to by ‘larger than’, it is because we have an interest in its formal properties that are independent of the contingencies of their instantiation”.

In other words, the universal BIGGER THAN doesn’t need the moon, Earth or anything else concrete to have being. Indeed the universal BIGGER THAN need never be instantiated between any two concrete objects.

This is the classic position of Plato.

Aristotle, on the other hand, believed that universals must be instantiated.

Ladyman and Ross round this off by making their Platonist position (at least in this specific respect) explicit. They write:

“To say that all that there is are relations and no relata, is therefore to follow Plato and say that the world of appearances is illusory.”

Let’s be explicit here.

The “world of appearances” includes carrots, cups and other human persons. (It certainly doesn’t include subatomic particles.) Yet in order to get to the Platonic truth, we must cut through such appearances (which are “illusory”) and discover the mathematical structures of what it is we’re examining. Alternatively, we must discover the universals and mathematical structures which underpin appearances.