The philosopher Michael Dummett called Ludwig Wittgenstein a “full-blooded conventionalist” and even an “anarchist” when it came to his philosophy of mathematics. Other philosophers — mainly Wittgensteinians — strongly reject these accusations. Nonetheless, convention — obviously! - plays a part in mathematics.

Firstly, it must be said that that it’s hard to tie all of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s positions and comments on mathematics together into a single ism. (Not that putting a philosopher in a neat and tidy box is of supreme importance.) And that may not simply be because Wittgenstein’s views are “so deep”. It may partly (or even largely) be because Wittgenstein’s prose style makes things very difficult. And it may also be because Wittgenstein is believed to have contradicted himself at various places — even during the same “period”.

Of course, it would be up to me to demonstrate all this with mountains of textual exegesis, which many Wittgenstein-obsessed writers and philosophers have indeed endlessly done over the decades (i.e., in order to advance their own hermeneutics of Wittgenstein). (See ‘Taking Wittgenstein at His Word: A Textual Study’ by Robert Fogelin.)

Conventionalism

The word “conventionalist” will be used in this essay. This is how many philosophers — and others — have seen Wittgenstein’s (“late”) philosophy of mathematics. (See ‘Convention’.) That’s certainly how the philosopher Michael Dummett (1925–2011) saw Wittgenstein’s philosophy of maths. Indeed, Dummett used the rhetorical words “full-blooded conventionalist” and even “anarchist” about Wittgenstein’s philosophy.

Dummett expressed Wittgenstein’s position in this way:

“What makes a [mathematical] answer correct is that we are able to agree in acknowledging it as correct.”

Yet Dummett’s very own verificationism seems (at least to some extent) conventionalist in nature. (See ‘Verificationism’ and ‘Dummett’s Verificationism’.) So perhaps all this is largely a dispute regarding the semantics of the term “conventionalism”.

That said, Dummett’s words (directly above) about Wittgenstein’s philosophy of mathematics may not be entirely about (mere) convention. After all, there also needs to be some kind of agreement about (what are taken to be) mathematical truths — otherwise we’d be in the situation in which an individual mathematician could have his own truths about his own mathematical statements, and even his own individual ways of establishing such truths.

So there must be some form of intersubjectivity involved here.

And in order to achieve that, conventions will be at least part of the story.

Of course, many Wittgenstein experts dispute the categorisation of “conventionalist”. (The Wittgenstein acolyte P.M.S Hacker regards it as blasphemy — see here.) That’s partly because disputes on “what Wittgenstein really meant” are legion.

Yet such experts can cite Wittgenstein’s own words to back up their positions.

For example, in Wittgenstein’s Remarks on the Foundations of Mathematics (which is largely made up of posthumously-published lectures, etc.), we have this:

“Mathematical truth isn’t established by their all agreeing that it’s true.”

As well as the following from the same book:

“[I]t has often been put in the form of an assertion that the truths of logic are determined by a consensus of opinions. Is this what I am saying? No.”

So Wittgenstein-was-not-a-conventionalist philosophers may well have a point — as we shall soon see.

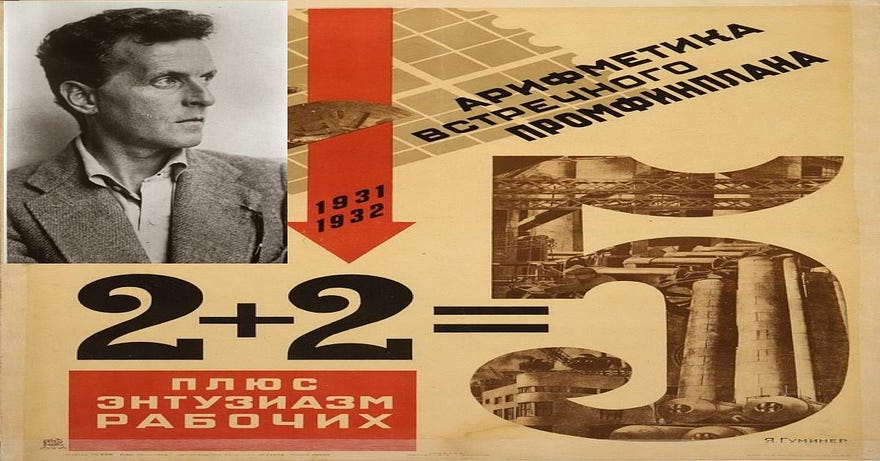

The Arithmetical Statement “2 + 2 = 4”

What does Wittgenstein’s general position on mathematics amount to?

To make things simpler: what about Wittgenstein’s take on a single arithmetical statement - say, “2 + 2 = 4”?

Firstly, Wittgenstein makes a distinction between a reading of a mathematical statement in terms of the (simply put) conventions it abides by, and what that statement actually means.

So is it the case that the statement “2 + 2 = 4” is taken to be true entirely because of the conventions we use?

It certainly the case that the symbols in that arithmetical statement are conventional. That is, we needn’t have used the symbols “2”, “+”, “4” and “=”. (Other cultures have different numerals and symbols for numbers.) We could just as easily have used the symbols and words “flip”, “flop”, “@” and “Kripke”.

So what about the meaning of the statement “2 + 2 = 4”?

On a simplistic, naive or even political reading, someone may say that the meaning of the statement “2 + 2 = 4” is the following:

Our society, at one point in history, decided that ‘4’ is the sum of ‘2 + 2’.

Of course this must mean that “our society” must also have decided what the word “sum” means and also what the symbols “+”, “=” and “2” mean. (That’s only if individual symbols can have a meaning outside of their statemental/sentential — and larger — contexts.)

In any case, Wittgenstein himself expressed a very simple argument against this position.

In his Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein wrote the following:

“Certainly, the propositions ‘Human beings believe that twice two is four’ and ‘Twice two is four’ do not mean the same.”

The meaning of the statement “2 + 2 = 4” can’t literally be, “Our society, at one point in history, decided that ‘4’ is the sum of ‘2 + 2’” (or anything similar to that).

Those words are, after all, a description of symbol-use, historical and sociological facts, etc. And such descriptions may also include facts and views about why, when and how Western culture made these decisions about these symbols.

In any case, the statement “Our society, at one point in history, decided that ‘4’ is the sum of ‘2 + 2’” could be applied to any arithmetical or mathematical statement. Or, more accurately, the clause “Our society, at one point in history, decided that […]” could be applied to any statement.

So those words (or facts) can’t be the meaning of this particular mathematical statement. That is, talk of symbols, conventions, history, etc. won’t tell us about a particular mathematical statement.

Platonism and the Techniques of Mathematics

Wittgenstein offered a position on mathematical statements which may (repeat: may) seem conventionalist. Indeed, Wittgenstein’s anti-Platonism can appear to go in a conventionalist direction.

Wittgenstein’s philosophy of mathematics can also be seen as going in a sociological, psychological and even (as some have argued) “anthropocentric” direction. (None of these things automatically contradict conventionalism.)

Yet Wittgenstein himself went way beyond mere talk of convention.

For example, Wittgenstein wrote:

“The proposition is grounded in a technique. And, if you like, also in the physical and psychological facts that make the technique possible.”

Technique?

Well, Wittgenstein himself provided an everyday example of this. He wrote:

“I say to, ‘You know what you’ve done so far. Now do the same sort of thing for these two numbers.’ [] Now everybody is taught to do it — and now there is a right and wrong. Before there was not.”

If Wittgenstein was arguing exclusively against mathematical Platonists, then surely it can’t be said that such people would have disagreed with his words directly above. (As ever with Wittgenstein, that depends on how his words are read or interpreted.)

Few mathematical Platonists — or few people — would deny that mathematics is “grounded in a technique” (or in techniques in the plural) — even if that technique is itself grounded in an abstract Platonic realm. That is, even if a Platonic realm does exist, then mathematicians and laypersons will still require techniques, skills, symbols, conventions, particular psychological states, etc. in order to (as it were) access that realm.

Moreover, who’d argue that these facts about mathematical technique/s would constitute the “sense” (or the meaning) of the statement “2 + 2 = 4” — or the meaning of anything else in mathematics for that matter?

Again, few mathematical Platonists or anti-conventionalists would deny that conventions — and what Wittgenstein called “practices” — are required when it comes to communities of mathematicians or even the many laypersons who use mathematics. And, again, it’s hard to believe that anyone believes that the facts about techniques, psychological states, symbol-use, etc. constitute the meaning (or sense) of “2 + 2 = 4”.

Of course, all this will depend on what, precisely, Wittgenstein meant by the word “sense”. Indeed, it will also depend on what Wittgenstein took other philosophers to have meant by that word.

Yet it’s clear here that Wittgenstein did believe that at least some philosophers did take the technique (as it were) behind the statement “2 + 2 = 4” to be the sense.

So all this must also mean that, on a Wittgensteinian reading, the statement “2 + 2 = 4” must also be grounded in a technique.

And that technique will also be grounded on the adder’s knowledge of the symbols, how he was taught arithmetic, etc. It will also depend on his or her psychology, psychological states, etc…

But so what?

Again, why would a mathematical Platonist — or anyone else — deny all that?

So who was Wittgenstein arguing against?

Perhaps Wittgenstein’s conclusion to the passage above answers that question. He continued:

“But it doesn’t follow that its sense is to express these conditions.”

These words seem to go against any purely conventionalist reading of Wittgenstein’s position. That is, obviously mathematical conventions exist. However, there is — or must be — more to the story of mathematics than that.

More particularly, the sense of the statement “2 + 2 = 4” isn’t merely about conventions, symbols, techniques, psychological sates, “rules”, historical facts, etc.

Yet strangely enough, Wittgenstein himself used the word “proposition” in the third-to-last passage above.

So what is a (mathematical) proposition?

Mathematical Platonists — and others — will make a distinction between the (abstract) proposition itself (say, 2 + 2 = 4) and everything else. Indeed, even Wittgenstein himself said that the proposition “is grounded in a technique”. That too hints at a separation between the proposition itself and the (later?) technique (plus everything that’s part of that technique).

Yet Wittgenstein didn’t actually believe that the statement “2 + 2 = 4” is about a proposition (or that it “states a proposition”). That is, the symbolic statement “2 + 2 = 4” doesn’t tell us about (or refer to) the abstract reality that is (supposed to be) 2 + 2 = 4 (or 2 plus 2 equalling 4).

Conclusion

In general terms, Wittgenstein appeared to conflate (or perhaps simply distinguish) convention and intersubjectivity with (mere) “opinions” and “convictions”. In Remarks on the Foundations of Mathematics, for example, he wrote:

“The agreement of people in calculation is not an agreement in opinions or convictions.”

So, instead, Wittgenstein focused on psychological habits, empirical regularities (i.e., the objects we count, things generally, etc.) and, indeed, on a “form of life”. In other words, Wittgenstein characteristically believed that mathematics isn’t about “agreement in opinions or convictions”: it’s about a form of life.

************************************

Note: What is a Statement?

The word “statement” was used many times in the essay above. That word was used instead of “proposition”. Yet some philosophers use the word “statement” as a synonym of “proposition”. That is, they argue that “different sentences can express the same statement”. Other philosophers say: “Different sentences can express the same proposition.” Thus, in that sense, a statement is taken to be as abstract as a proposition.

In the essay above, however, statements are taken to be natural-language sentences — or grammatical “strings” of symbols — which are either true or false. That is, statements aren’t taken to be abstract objects or entities in the mind or brain.

Of course all this is complicated by the fact that three (not two) distinctions have been made in philosophical literature. That is, distinctions have been made between sentences, statements and propositions.

A statement has been taken to be a sentence that’s either true or false. This conception of a statement is roughly identical to the position on a proposition. However, a statement has also been seen as the “semantic content of a meaningful declarative or descriptive sentence”. And so on and so on.