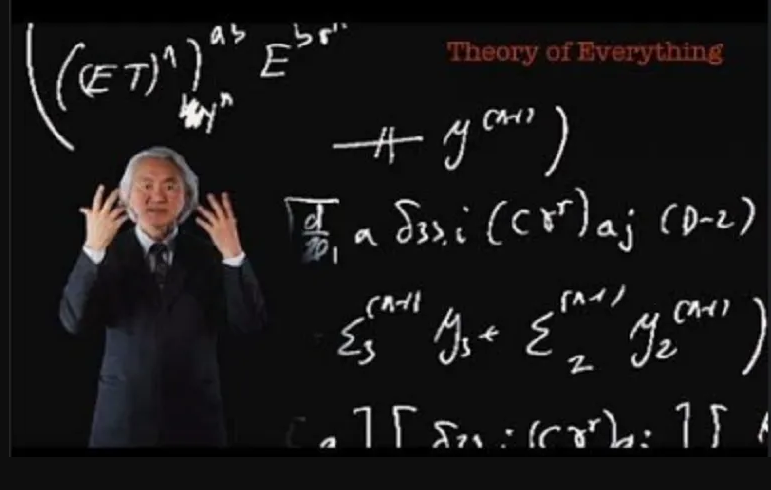

In the mid-1990s, the science journalist John Horgan interviewed various physicists (including Sheldon Glashow, Edward Witten and Steven Weinberg) who spoke both for and against the strongly speculative (or “nonempirical”) nature of much contemporary physics and cosmology. After Horgan wrote The End of Science, Roger Penrose, Lee Smolin, the writer David Berlinski and Michio Kaku also spoke both for and against (what’s rhetorically called) postmodern physics.

[In the following essay, the quotes from Edward Witten, Stephen Weinberg, Sheldon Glashow, Frank Tipler, David Schramm and Howard Georgi all come from John Horgan’s book The End of Science. The quotes from Lee Smolin, David Berlinski, Michio Kaku, Roger Penrose, Brian Greene, Martin Rees and Jim Holt come from various other books, papers and interviews.]

Firstly, the words “postmodern physics” are at least partly rhetorical in nature. Secondly, no physicist classifies his own physics as postmodern. Thirdly, even those physicists who see certain theories — i.e., those offered by other physicists — as being far too speculative (or “nonempirical”) in nature don’t classify them as postmodern.

Another problem with using the words “postmodern physics” is that they can be read in two different ways:

(1) As referring to the “critiques” of physics and science by postmodernist philosophers, sociologists, political activists, etc.

(2) As referring to physics that goes beyond observations, experiments, tests, predictions, etc.

(1) and (2) can be connected to each other. However, this essay will concentrate entirely on (2). The science journalist John Horgan, on the other hand, tackled both (1) and (2) in his book The End of Science.

In the case of (1) above, Horgan wrote:

“[O]ne of science’s dirty little secrets is that many prominent scientists harbor remarkably postmodern sentiments. My book provides ample evidence of this phenomenon. Recall Stephen Jay Gould confessing his fondness for the seminal postmodern text Structure of Scientific Revolutions [by Thomas Kuhn]; Lynn Margulis declaring, ‘I don’t think there’s absolute truth, and if there is, I don’t think any person has it’; Freeman Dyson predicting that modern physics will seem as primitive to future scientists as the physics of Aristotle seems to us.”

As it is, I don’t see all of these positions as being particularly postmodern in the sense of (1) above. (Unless, that is, one strictly adheres to Horgan’s particular take on “ironic science”.) However, a couple are postmodern in the sense of (2) above. This means that Horgan used the word “postmodern” both loosely and rhetorically. However, exactly the same can be said about the way the term “postmodern” is used in this essay.

As another example of (1) above, Horgan quoted physicist Robert Lee Park speaking about Horgan’s own book, The End of Science. Park is quoted as stating the following:

“Science has manned the battlements against the postmodern heresy that there is no objective truth, only to discover postmodernism inside the wall.”

So it may well be the case that Horgan’s “ironic science” is a better (or at least a more colourful) term than “postmodern physics”. That said, Horgan uses the word “postmodern” too.

Theoretical physicist Lee Smolin (1955-) also used the words “postmodern physics” in his 2006 book The Trouble With Physics. He wrote:

“The feeling was that there could be only one consistent theory that unified all of physics, and since string theory appeared to do that, it had to be right. No more reliance on experiment to check our theories. That was the stuff of Galileo. Mathematics [alone] now sufficed to explore the laws of nature. We had entered the period of postmodern physics.”

The science writer and author Jim Holt put a fairly similar point in this way:

“For the first time in its history, theory has caught up with experiment. In the absence of new data, physicists must steer by something other than hard empirical evidence in their quest for a final theory.”

Smolin’s description of string theory, and his use of the words “postmodern physics”, aren’t really (or even at all) references to philosophical postmodernism in the sense practised by philosophers like Jean Baudrillard, Jean-François Lyotard, etc. Smolin simply meant after modern physics. (Of course, Smolin must have been aware of the philosophical associations of this term.) More specifically, Smolin believed that this is how physics — at least as carried out by certain physicists — came to be done when string theory arrived on the scene.

In terms of ironic science, this is what Horgan himself had to say about it:

“[I]ronic science, science that is not experimentally testable or resolvable even in principle and therefore is not science in the strict sense at all. Its primary function is to keep us awestruck before the mystery of the cosmos.”

Keeping to his literary theme, Horgan also used the term “strong scientists”, which is his variation on “Bloom’s ‘strong poets’”.

[See Horgan’s ‘How Harold Bloom, the Late Literary Critic, Helped Me Write The End of Science’ for Scientific American. See also detail on Harold Bloom’s notion of “strong poets” here.]

Strong scientists are

“those who are seeking to misread and therefore transcend quantum mechanics or the big bang theory or Darwinian evolution”.

Horgan then offered us an example of a strong scientist: Roger Penrose. He wrote:

“Roger Penrose is a strong scientist. For the most part, he and others of his ilk have only one option: to pursue science in a speculative, postempirical mode that I call ironic science.”

It’s ironic, then, that Penrose himself has criticised this “speculative, postempirical” and, therefore, ironic science. (Of course, Penrose himself doesn’t use the words “ironic science”.) That is, Penrose, like Smolin, mainly — or even exclusively — had string theory in mind. (See final section.)

It’s also surprising how widespread Horgan believes ironic science to be. He cites

“such ironic hypotheses as the anthropic principle, inflation, multi-universe theories, punctuated equilibrium, and Gaia”

as examples of ironic science.

Elsewhere, Horgan adds A.I. futurologists (not his term) to this list when he tells us that such people “are not practicing science, of course, but ironic science, or wishful thinking”. He also has qualms about evolutionary psychology (i.e., in these “postempirical” respects).

It’s not only odd that so many scientific theories are deemed to be part of ironic science by Horgan: it’s also odd that some of the upholders of these scientific theories deem other scientific theories (i.e., not their own) to be ironic (or postmodern).

For example, Steven Jay Gould didn’t have any time for Gaia (“a metaphor, not a mechanism”). Many who accept inflation and the multiverse are also critical of the anthropic principle. And, who knows, perhaps Gaia theorists are critical of the human-centred nature of the anthropic principle. (This is often denied by those scientists and philosophers who endorse it.)

Of course, Horgan isn’t on his own when it comes to his account of ironic science. Many religious critics of science, philosophers, sceptical commentators, etc. have noted the speculative nature of contemporary physics and cosmology.

Take the case of David Berlinski.

David Berlinski Against Postmodern Physics

David Berlinski (1942-) is a controversial writer and polemicist. Indeed, some commentators see him as being a mere “contrarian”. (See ‘Ode to the Contrarian’, which features Berlinski.) Berlinski classes himself as a “counter-puncher”.

It’s a little ironic that Berlinski has a position on postmodern physics and cosmology which is very similar to Horgan’s own. However, it can be assumed that Horgan wouldn’t like to be associated with Berlinski because they’re at odds politically, as well as (I believe) on the nature and role of religion. Thus, Berlinski’s and Horgan’s criticisms of postmodern physics and cosmology come from different angles (or starting points).

In more detail. Berlinski comes at postmodern physics and cosmology from a mainly political (as well as contrarian?) angle. He also approaches it from a position which is very defensive of religion. (Berlinski is against “the attack on religious thought”.) However, Berlinski categorically denies being religious himself (see here.) In that sense, then, Berlinski is not that unlike — shock, horror! — Stephen Jay Gould. (See my ‘Stephen Jay Gould on Science and Religion: The Politics of Non-Overlapping Magisteria’.)

Berlinski’s broader perspective on science is best expressed in his book The Devil’s Delusion: Atheism and its Scientific Pretensions (2008). Berlinski is also a signatory to A Scientific Dissent from Darwinism, which was a statement issued by the (“politically conservative”) Discovery Institute in 2001.

Berlinski’s targets are also as wide as Horgan’s own.

In detail. Berlinski rejects — or, perhaps, simply questions — the big bang theory, the theory of evolution, and inflationary theory. He also rejects (or simply questions) the existence of black holes, the multiverse, etc.

In his essay ‘Was There a Big Bang?’ (1998), Berlinski wrote:

“What are discovering is that many areas of the universe are apparently protected from our scrutiny, like sensitive files sealed from view by powerful encryption codes.”

Now the passage above — i.e., at least taken on its own — could actually be about the multiverse theory, the extra dimensions and branes of string/M- theory, and God knows what else…

Yet it must be said here that such critical and sceptical words have also been uttered (as will be shown) by some well-known and high-ranking physicists themselves — even if their prose styles are very unlike Berlinski’s own.

Reading Berlinski’s words, then, it seems that he targets all these scientific theories because none of them adhere to his strict Machian or positivist (or logical empiricist) position on science. The ironic thing here, however, is that Berlinski most certainly wouldn’t see himself as being either a Machian or a positivist, primarily because positivism is strongly associated with scientism and many other (retrospective) sins.

It must also be said that Berlinski does actually cite various examples from contemporary physics and cosmology. He also offers us some technical detail.

For example, Berlinski wrote:

“Unhappy examples are everywhere; absurd schemes to model time on the basis of the complex numbers, as in Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time, bizarre and ugly contraptions for cosmic inflation; universes multiplying beyond the reach of observation; white holes, black holes, worm holes, and naked singularities; theories of every strip and variety, all of them uncorrected by any criticism beyond the trivial.”

Berlinski takes the extreme and (to use a word he often uses) absurd position that all speculation — and indeed all hypothesising — in physics and cosmology is beyond the pail — or, to use the word of this essay, postmodern. Yet if such a position on speculation had ever been (as it were) made law, then that would have destroyed almost all physics from day one.

Berlinski also seems to be ignorant of the history of science (or simply one aspect thereof) when he uses phrases such as “there is no evidence whatsoever in favour of” various contemporary theories in theoretical physics and cosmology. Yet he should — and probably does — know that all sorts of theories which began life as hypotheses — or even straight speculations — were later backed up by observations, tests, experiments, data/evidence, etc.

All this was true of Maxwell’s kinetic theory, Paul Dirac’s postulation of an “anti-electron”, Murray Gell-Mann’s “quark model”, etc. There are, of course, many other examples. Indeed, it can be assumed that physicists themselves could provide a list that’s as long as their collective arm…

Unless, that is, Berlinski rejects all these theories and entities too.

To ask a simple question:

Is Berlinski ruling out — a priori — all future observational and experimental backup for literally all the speculations of theoretical physicists and cosmologists?

So what does Berlinski himself believe?

He believes the following:

“This scrupulousness has been compromised. The result has been the calculated or careless erasure of the line separating disciplined physical inquiry from speculative metaphysics. Contemporary cosmologists feel free to say anything that pops into their heads.”

Are such speculations (i.e., from theoretical physicists and cosmologists) automatically (to use Berlinski’s word) “metaphysics” simply because there’s no observational and/or experimental evidence for them at the present time? Indeed, would the metaphysical status of such speculations automatically be a bad thing if, at least in principle, future findings, tests, observations, experiments, etc. would turn them (as it were) non-metaphysical?

It’s worth stressing here that Berlinski isn’t a scientist. However, Brian Greene, Martin Rees, Sheldon Glashow, David Schramm and Howard Georgi are - and they too recognise the problems with postmodern physics and postmodern cosmology. (Arguably, cosmology actually began life as a postmodern discipline, as Michio Kaku argues later.)

Physicists Against Postmodern Physics

Take as an example theoretical physicist Brian Greene’s words of warning on the idea of a multiverse. He states:

“The danger, if the multiverse idea takes root, is that researchers may too quickly give up the search for such underlying explanations. When faced with seemingly inexplicable observations, researchers may invoke the framework of the multiverse prematurely — proclaiming some phenomenon or other to merely reflect conditions in our own bubble universe and thereby failing to discover the deeper understanding that awaits us.”

In addition, the cosmologist and astrophysicist Martin Rees also said more or less the same thing as Brian Greene in the following:

“If people believed that some features of the universe were not fundamental but just accidents, resulting from the particular way our domain in the meta-universe cooled down, then they’d be less motivated to try to explain them.”

Of course, string theory has been deemed to be the prime — sometimes only — example of postmodern physics. So this is a good place to bring in the American theoretical physicist Sheldon Glashow (1932-).

Glashow argued that string theorists have (as it were) jumped the gun. He said:

“Now, are we so arrogant as to believe we have all the experimental information we need right now to construct that holy grail of theoretical physics, a unified theory? I think not. I think certainly there are surprises that natural phenomena have in store for us, and we’re not going to find them unless we look.”

Thus, in the process of jumping the gun, string theorists were basically indulging in postmodern physics.

Sheldon Glashow and Paul Ginsparg also wrote the following:

“Contemplation of superstrings may evolve into an activity as remote from conventional particle physics as particle physics is from chemistry, to be conducted at schools of divinity by future equivalents of medieval theologians.”

As with Horgan earlier, it can be argued that there may be nothing specifically postmodern about the situation highlighted by Glashow. After all, even though there’s a very large distance between particles physics and the “contemplation of superstrings”, superstring theorists still (as it were) stand upon (even though they believe they supersede) particle physics and the standard model. However, Glashow’s interpretation of this situation paints it as being postmodern. That is, his last clause (i.e., “to be conducted at schools of divinity by future equivalents of medieval theologians”) is clearly putting a interpretation of this situation as being one of postmodern physics… Or, in Glashow’s own terms, theological physics.

Glashow’s next words seal his interpretation of postmodern physics. He continued:

“[F]or the first time since the Dark Ages, we can see how our noble search may end, with faith replacing science once again.”

Now for the American astrophysicist David Schramm (1945–1997) on inflation.

Schramm gave a technical explanation as to why inflation is postmodern. He said:

“I like inflation, but it can never be thoroughly verified because it does not generate any unique predictions that cannot be explained in some other way.”

He then compared inflation to the Big Bang:

“You won’t see that for inflation, whereas for the big bang itself you do see that. The beautiful, cosmic microwave background and the light-element abundances tell you, ‘This is it.’ There’s no other way of getting these observations.”

Schramm then moved on to superstring theory with these words:

“Even if somebody comes up with a really beautiful theory, like superstring theory, there’s not any way it can be tested. So you’re not really doing the scientific method, where you make predictions and then check it. There’s not that experimental check going on. It’s more mathematical consistency.”

Now for the American physicist Howard Georgi (1947-) on quantum cosmology.

Firstly, Georgi stated his position in relation to his own discipline:

“A simple particle physicist like myself has trouble in those uncharted waters.”

Georgi’s specific target is quantum cosmology.

After reading various papers on quantum cosmology, Georgi found all the talk about wormholes, time travel and baby universes “quite amusing”. Indeed, he believed it was “like reading Genesis”.

Georgi’s way of putting things is very much like David Berlinski’s.

(Perhaps Berlinski has been strongly dependent — and reliant — upon what these physicist critics of postmodern physics have written and said.)

What about Georgi on inflation (also sneered at by Berlinski)?

Georgi believes that it’s a

“wonderful sort of scientific myth, which is at least as good as any other myth I’ve ever heard”.

Again, Georgi’s words almost exactly chime in with Berlinski’s own. Indeed, Berlinski also uses the word “myth” in his writings.

Now, despite everything that’s just been written, some of the proponents of postmodern physics know exactly what’s going on here.

Physicists Defend Postmodern Physics

Take Michio Kaku talking about cosmology in the 1960s.

In his 2004 book Parallel Worlds, Kaku wrote:

“[Cosmology] was not an experimental science at all, where one can test hypotheses with precise instrument, but rather a collection of loose, highly speculative theories.”

Kaku also told us how physics used to be before string theory:

“In the past, physics was usually based on making painfully detailed observations of nature, formulating some partial hypothesis, carefully testing the idea against the data, and then tediously repeating the process, over and over again.”

Despite the above being a simplified picture (which Kaku wouldn’t deny) of modern physics, Kaku pits all this against the approach employed by string theorists. He continued:

“String theory was a seat-of-your-pants method based on simply guessing the answer. Such breathtaking shortcuts were not supposed to be possible.”

It’s clear that Kaku and many other string theorists are well aware that string theory has been seen as being postmodern (i.e., even if that precise word isn’t used). So it seems odd (at least prima facie) that a string theorist would admit that string theory was based on “simply guessing”. Then again, guessing (or at least speculation) has always been a part of physics. Thus, string theory isn’t entirely unique in this respect.

Again, even according to a string theorist himself (i.e., Kaku), whereas modern physics involved observations, tests and experiments, postmodern string theory is (to be rhetorical?) all about mathematics… and guessing.

String theory is certainly (to put it mildly) very mathematical.

Indeed, not only is string theory seemingly more dependent on maths than most other areas of physics, it seems that many physicists actually see it as being a branch of mathematics.

Kaku himself doesn’t hide from all this. He quotes a “Harvard physicist” saying as much. In Kaku’s own words:

“One Harvard physicist has sneered that string theory is not really a branch of physics at all, but actually a branch of pure mathematics, or philosophy, if not religion.”

That Harvard physicist was none other than (to use Kaku’s words) “Nobel Laureate Sheldon Glashow”.

Now for the postmodern physicist Edward Witten.

Edward Witten

The American mathematical physicist Edward Witten (1951-) defended the postmodern nature of superstring theory in exactly the same way in which all (or at least most) other superstring theorists had done. He said:

“Even though it is, properly speaking, a postprediction, in the sense that the experiment was made before the theory, the fact that gravity is a consequence of string theory, to me, is one of the greatest theoretical insights ever.”

The upshot here is that although string theory didn’t actually predict gravity, in nonetheless necessarily includes it. To laypersons at least, this may not seem like much of a claim. After all, this isn’t about string theorists doing experimental work on gravity or discovering any new or odd phenomena. Yet string theory still accounts for gravity, as well as its relation to all the forces and particles. More importantly, string theory brings quantum theory and relativity together.

In any case, there must be very good reasons as to why postmodern physicists accept and propagate theories beyond the observational, evidential and experimental.

In response to John Horgan’s doubts, Edward Witten put it this way:

“I don’t think I’ve succeeded in conveying to you its wonder, its incredible consistency, remarkable elegance, and beauty.”

[Perhaps Witten was really talking about his own M-theory here. Witten had first “conjectured” such a theory in 1995, a year before The End of Science was published.]

So what, exactly, displays “incredible consistency, remarkable elegance, and beauty”?

It’s the mathematics embedded in superstring theory.

Witten then elaborates:

“Good wrong ideas are extremely scarce, and good wrong ideas that even remotely rival the majesty of string theory have never been seen.”

Interestingly enough, Michio Kaku quoted the physicist and astrophysicist Joel Primack saying pretty much the same thing about inflation (i.e., not string theory). Primack said:

“No theory as beautiful as this has ever been wrong before.”

Now meet our last postmodern physicist.

Steven Weinberg

Weinberg too defends postmodern physics (without, of course, using those last two words).

In terms specifically of string theory, Weinberg said:

“I agree strings are much farther away from direct perception than atoms, and atoms are much farther away from direct perception than chairs, but I don’t see any philosophical discontinuity there.”

In that sense, then, string theory isn’t (particularly) postmodern at all.

Prima facie, one way string theory isn’t postmodern (at least according to Weinberg) is that if a string theorist posted “the final, correct version of superstring theory on the Internet [and] she got results that agreed with experiment”, then all of us should simply say, “That’s it.”

Thus, at least experiment provides the final word here.

Finally, when critics of postmodern physics and cosmology say that it’s all (purely) speculative in nature, then a postmodern physicist or cosmologist can always respond in the way that the American mathematical physicist and cosmologist Frank Tipler (1947-) responded. He said:

“Secretly, I think of myself as standing in the same position as Copernicus.”

Indeed, this is the kind of response you actually find in the writings of many postmodern physicists.

Now take the case of Roger Penrose, who can be interpreted as offering a midway position between modern physics and postmodern physics.

Penrose’s Modern Physics and Postmodern Twistor Theory?

Despite Roger Penrose’s stress on the fundamental importance of mathematics in physics (which is almost like stressing the obvious), Penrose has still been highly suspicious of string theory.

Although Penrose doesn’t name any names, he warns his readers that if physics is not

“able to be guided in detail by experiment, [it] must rely more and more heavily on an ability to appreciate the physical relevance and depth of the mathematics, and to ‘sniff out’ the appropriate ideas by use of a profoundly sensitive aesthetic mathematical appreciation”.

This squares fairly well with what British science writer and astrophysicist John Gribbin had to say.

Gribbin talked in terms of what he called a “physical model” of “mathematical concepts”. He wrote (in his Schrodinger’s Kittens and the Search for Reality) that a “strong operational axiom” tells us that

“literally every version of mathematical concepts has a physical model somewhere, and the clever physicist should be advised to deliberately and routinely seek out, as part of his activity, physical models of already discovered mathematical structures”.

Yet even in Gribbin’s case, it’s still clear that a “mathematical concept” comes first, and only then is a “physical model” found to square with it.

Penrose’s words on his twistor theory are also relevant here.

Interestingly, just after criticising string theorists for divorcing their mathematics from experiment, prediction, observation, etc, Penrose then freely confesses that he’s — at least partly — guilty of exactly the same sin!

Firstly, Penrose tells us about the “pure mathematics” of his own twistor theory. He writes:

“Yet twistor theory, like string theory, has had a significant influence on pure mathematics, and this has been regarded as one of its greatest strengths.”

After that, there’s this confession from Penrose:

“That is all very well, the candid reader might be inclined to remark with some justification, but did I not complain [] that a weakness of string theory was that it was largely mathematically driven, with too little guidance coming from the nature of the physical world? In some respects this is a valid criticism of twistor theory also. There is certainly no hard reason, coming from modern observational data, to force us into a belief that twistor theory provides the route that modern physics should follow. [] The main criticism that can be levelled at twistor theory, as of now, is that it is not really a physical theory. It certainly makes no unambiguous physical predictions.”

String theory particularly has also often been criticised for not making “unambiguous physical predictions”. Yet here’s Penrose saying exactly the same thing about his very own twistor theory.

So how does Penrose extract himself from all this?

The obvious question to ask here is the following:

What is twistor theory doing right that string theory is doing wrong?

Is the answer to that question entirely determined by which theory is closer to “the nature of the physical world”?

Surely it must be.

However, don’t we only (as it were) get to the physical world through a mathematical theory? Or as Stephen Hawking once put it:

“If what we regards as real depends on our theory, how can we make reality the basis of our philosophy? But we cannot distinguish what is real about the universe without a theory. [] Beyond that it makes no sense to ask if it corresponds to reality, because we do not know what reality is independent of theory.”

So perhaps it’s the case that (as Penrose may believe) the mathematics of twistor theory is superior to the mathematics of string theory.

Finally, there probably never is (to use Penrose’s words) “a hard reason to force” us to believe any physical theory — at least not in the early days of such a theory. This obliquely brings on board the largely philosophical idea of the underdetermination of theory by data. That is, the “modern observational data” which Penrose mentions will never be enough to force the issue as to which theory to accept. This basically means that whatever observational data there is can be interpreted (or theorised about) in many different ways. Alternatively, the same observational data can produce — or be explained by — numerous (often rival) physical theories.

My flickr account and Twitter account.