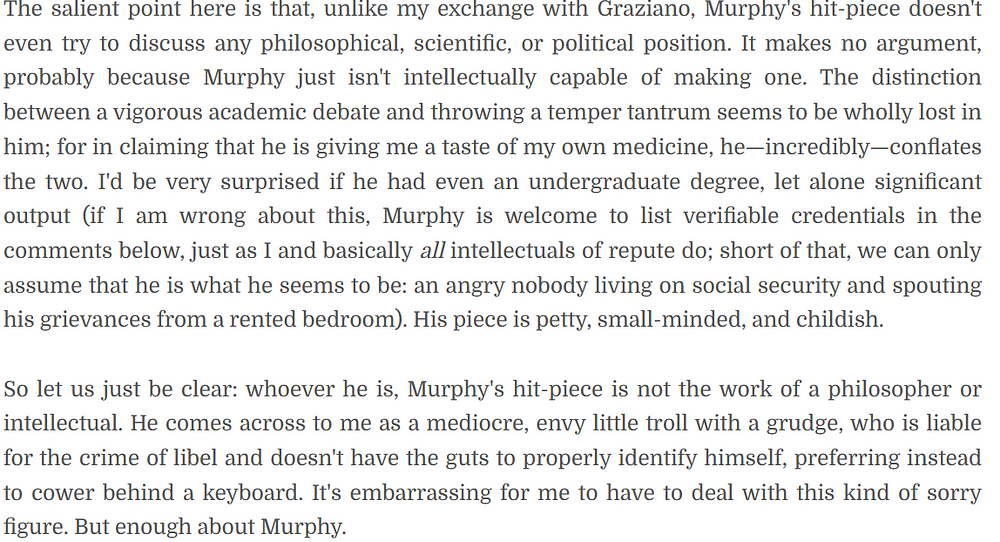

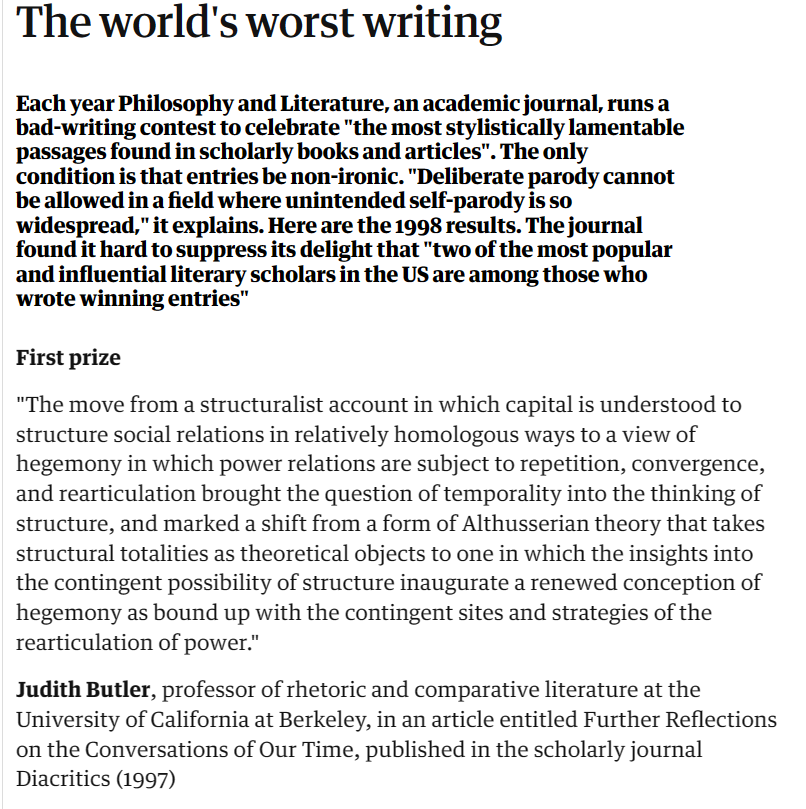

“The move from a structuralist account in which capital is understood to structure social relations in relatively homologous ways to a view of hegemony in which power relations are subject to repetition, convergence, and rearticulation brought the question of temporality into the thinking of structure, and marked a shift from a form of Althusserian theory that takes structural totalities as theoretical objects to one in which the insights into the contingent possibility of structure inaugurate a renewed conception of hegemony as bound up with the contingent sites and strategies of the rearticulation of power.”

— Judith Butler

The passage above was awarded first prize in the annual Bad Writing Contest in 1998. [This prize will be discussed in the essay which follows.]

“To the extent that the naming of the ‘girl’ is transitive, that is, initiates the process by which a certain ‘girling’ is compelled, the term or, rather, its symbolic power, govern the formation of a corporeally enacted femininity that never fully approximates the norm. This is a ‘girl,’ however, who is compelled to ‘cite’ the norm in order to qualify and remain a viable subject.”

— Judith Butler

That’s my own example from Judith Butler. This passage is from her paper ‘Critically Queer’ (1993). [See note 1.]

Introduction

In 1998, Judith Butler was awarded first prize in the annual Bad Writing Contest, which was established by the journal Philosophy and Literature. And one year later (in 1999), Butler’s prose was again lampooned in a Wall Street Journal editorial. (See ‘Language Crimes’.)

So why does the American gender theorist Judith Butler write in such a peculiar way?

It’s mainly because her writing style was adopted by certain (largely American) elite academics, in certain (largely American) elite universities, at a certain point in history…

These elite academics adopted this prose style primarily to hide and obscure their bad arguments (or even their total lack of arguments), their banal ideas, and their truisms.

Yet all this was also done — perhaps paradoxically — to advance various political causes.

It also needs to be said here that it’s all been a great means of advancing the careers of “elite and radical” academics at various elite and radical university departments.

More relevantly, the French philosopher Jacques Derrida may also provide a clue when it comes to Judith Butler’s pretentious and obscurantist writing style.

Judith Butler and Jacques Derrida

Judith Butler is very much influenced by Derrida. Indeed, in an obituary for the London Review of Books (‘Jacques Derrida’), she wrote that

“[i]t is surely uncontroversial to say that Jacques Derrida was one of the greatest philosophers of the 20th century”.

Oddly enough, this obituary piece is clear and (fairly) easy to read. And that fact raises the following question:

Why could Butler write clear and simple prose for the London Review of Books, but not for academic journals, and other publications?

Was it because Butler wasn’t preaching to the (academically) converted when she wrote her London Review of Books piece?

Similarly, was it because she was writing for readers outside her own tribe of elite academics?

Let’s get back to Jacques Derrida and his influence on Judith Butler.

Julian Baggini on Jacques Derrida’s Writing Style

In a Prospect article called ‘Think Jacques Derrida was a charlatan? Look again’, the English philosopher Julian Baggini argued that Derrida’s actual philosophy was embedded in his “complex and difficult” prose style…

That doesn’t mean that Derrida’s philosophy couldn’t help but be written in complex and difficult prose because his philosophy itself is difficult and complex. It means that the complex and difficult prose is actually part of the philosophy.

Perhaps Baggini is on safe ground here because Derrida himself once wrote the following line: “To risk meaning nothing is to start to play.”

So does Derrida’s own statement above mean nothing?…

Is it an act of play?

Of course, both could be true.

In other words, the statement “To risk meaning nothing is to start to play” could itself be an act of play, and it could also mean something.

Perhaps Baggini’s words about “fixed meanings” and “false precision” provides an answer to these questions. He stated this:

“You can see why Derrida’s writing could never have been clear and plain.”

Baggini’s argument here is that Derrida’s meanings were themselves never fixed or precise. And that’s precisely because his actual writing style displays the unfixed and imprecise nature of the meanings therein…

Yet who’s to say that this is an accurate explanation of Derrida’s writing style.

Indeed, there are many other ways to explain Derrida’s prose, including some offered by Derrida himself.

For example, Baggini himself quotes Derrida saying — of himself — that he is “an incorrigible hyperbolite” who “always exaggerated”.

In addition, what of Derrida’s “the play of the sign” (with an emphasis on the word “play”). (This play was given voice in the earlier statement, “To risk meaning nothing is to start to play”.)

Relevantly enough, Baggini puts what he takes to be Derrida’s positions in his own simple prose…

So why couldn’t Derrida have done the same?

More specifically, why couldn’t Derrida have said (if only once!) the following (to borrow from Baggini’s own words)? -

… So you can see why my writing could never be clear and plain.

Similarly, why didn’t Derrida ever write something like the following? -

If you accept my premise that meanings cannot be fixed, then I’ll take pains to avoid any suggestion of false precision in my own writings.

Derrida possibly did write such a thing, but in a writing style which itself avoided any suggestion of false precision!

In other words, perhaps Derrida did once tell his fans and readers that his writing could never have been clear and plain, but he did so in a writing style which was itself unclear and obscure.

So was all this yet another case of Derrida simply playing games?

In any case, Baggini rounded all this off by saying that

“Derrida’s difficult style, far from being an affectation, is an inevitable requirement of his philosophy”.

Of course, loyal fans and defenders of Derrida will have noted that my account of Derrida’s play of the sign is critical, negative, and offered by someone outside any tribe of elite academics. Thus, to them at least, my words simply must be a misreading.

More relevantly, is Judith Butler’s own (to requote Baggini) “difficult style” an “inevitable requirement of [her] philosophy” too?

Back to Judith Butler

It’s worth saying here that Butler has been accused of “bad writing” so many times that she’s had a couple of decades (or more) to come up with… pretentious and obscurantist rationalisations for her pretentious and obscurantist writing style. She’s a skilled elite academic, after all. So Butler can verbally worm her way out of her own self-designed hermetically-sealed coffin.

Yet of course the claim here isn’t that Butler’s writing is pretentious and obscurantist… full stop!

There must, after all, be padding around Butler’s pretentiousness and obscurantism. That’s obviously because (as it were) pure pretentiousness and pure obscurantism hardly make sense within the context of her overall academic career, fame and notoriety. Thus, we also have countless proper names, references, footnotes, examples of jargon, etc. in Butler’s writings too.

Now it’s worth bringing in the arguments of the lecturer Dr. Cathy Birkenstein here.

Cathy Birkenstein on Judith Butler’s Writing Style

According to Cathy Birkenstein (in her paper ‘We Got the Wrong Gal: Rethinking the “Bad” Academic Writing of Judith Butler’), even Judith Butler’s fans and defenders admit that her prose style is… well, different.

Birkenstein writes:

“Surprisingly, then, many who defend Butler’s writing and the type of theoretical discourse it represents agree with Butler’s critics that her writing is inaccessible when judged by normative standards of accessibility. While Dutton, Nussbaum, and others condemn Butler’s alleged inaccessibility to mainstream readers, Butler and many of her allies praise that alleged inaccessibility on the grounds that it has the subversive potential to liberate those very same readers.”

It’s odd, then, that even in a defence of Butler’s pretentiousness and obscurantism we have the phrase “judged by normative standards of accessibility”…

What on earth does that mean?

Is accessible writing automatically or necessarily reactionary?

And why can’t “subversive” prose also be accessible? [See my essay ‘Chomsky on the Pretentiousness and Political Impotence of Postmodern Philosophy’.]

And why must accessible prose be tied to the “normative”?…

Hold on a minute.

Didn’t Julian Baggini answer these questions earlier when he argued that Derrida’s “writing could never have been clear and plain”?

Again, why is that?

According to Baggini, it’s because Derrida was battling against the pernicious and illusory notions of “fixed meanings” and “false precision”.

Now if we return to Birkenstein’s words above.

Are the slogan-filled defences of Butler’s writing style themselves “subversive [of] normative standards of accessibility”?

In any case, if even defences and introductions to Butler’s writings are themselves liberatory and arcane, then how does anyone ever get even a toehold into her work in the first place?

Do the relevant laypeople do so through the testimony of elite academics?

Do many of Butler’s fans and defenders have a kind of ignorant and uneducated faith in her prestigious — yet obscurantist — prose?

Oddly enough, Cathy Birkenstein herself doesn’t believe that Butler’s writing is “inaccessible and unintelligible”. Indeed, she believes that it

“conforms to those standards in ways that are missed by both her detractors and most of her defenders”.

Why does Birkenstein believe that Butler’s writings conform to such standards of accessibility? Birkenstein continues:

“The author’s own view is that, far from breaking from recognized standards of intelligibility, Butler’s writing conforms to those standards []. Though Butler’s writing certainly does have unclear moments, it would not have had the wide impact it has had were it not for its ability to consistently make recognizable arguments that readers can identify, summarize, and debate. Butler’s writing has succeeded in circulating as widely as it has in academic circles and beyond not because it breaks with the traditional pattern of ‘trad[ing] arguments and counter-arguments,’ as Nussbaum insists, but precisely because it makes systematic use of this classic argumentative pattern, and does so in ways that all writers (and readers) can learn from.”

As can be seen, Birkenstein’s main argument above is that Butler’s ideas and theories have (to use my own words) spread like wildfire, and there must be a good reason for this.

It’s true that Butler’s ideas and theories were given birth to in elite academia. However, then they filtered down to (to give my own examples) student unions, council offices, the BBC, CNN, the New York Times, massive corporations, and even to people (as it were) on the street.

Of course, it’s perfectly possible that pretentious and obscurantist prose can filter down. So there’s no obvious contradiction here.

Relevantly, pretentious and obscurantist prose can filter down when lesser mortals (i.e., non-academics) translate that prose, or when they offer their own interpretations of it.

Indeed, pretentious and obscurantist prose can even filter down to (as it were) the plebs well outside elite academia. All the activist plebs need do is memorise Judith Butler Lite. Indeed, at its most basic, all they need to do is consume and then mimic all those Butleresque social-media slogans and soundbites which usually have a very weak and circuitous relation to Butler’s actual academic papers.

Note

(1) It’s of course possible that Judith Butler’s writing style has changed since 1998. However, the academic and other works I’ve checked don’t show that. In any case, Butler gained her academic and political fame when she was writing the most pretentious and obscurantist prose of her career.