i) Introduction

ii) Brute Facts?

iii) David Chalmers and Christof Koch

iv) More Hard Questions?

v) Conclusion

The Australian philosopher David Chalmers is well-known for asking his “hard question”. It (sometimes) goes like this:

“Why should physical processing give rise to a rich inner life at all?”

Perhaps this question is similar to the following:

Why are the laws of physics (or the constants of nature) the way they are?

But what if these questions don’t have answers (or solutions)? What if the questions themselves are suspect? Despite stating that, even if a question may not have an answer; reasons or explanations still need to be given as to why that’s the case.

Compare the questions above to another possibly unanswerable (if ironic) question raised by the well-known theoretical physicist Richard Feynman. He recalled:

“You know, the most amazing thing happened to me tonight. I saw a car with the license plate ARW 357. Can you imagine? Of all the millions of license plates in the state, what was the chance that I would see that particular one tonight? Amazing!”

This passage from Feynman can be reformulated as this simple question:

Of all the millions of license plates in the state, why did I see that particular one tonight?

Of course this question isn’t in the same ballpark as the question “Why do physical states give rise to experience?” (or “Why are the laws of physics and constants of nature the way they are?”); though it may be on the borders of that question.

It’s not weird that Feynman should have seen that particular number plate. So it may not be such a deep mystery that a physical state (or states) should give rise to an experience or that the laws of physics (or the constants of nature) have some kind of nature (or the values that they do have).

Moreover, perhaps there’s no deep answer — other than mundane facts about probabilities — to the question as to why Feynman should have seen that number plate. Similarly with experience arising from the physical. That is, beyond the fact that these things are the way they are, there may be nothing more to say.

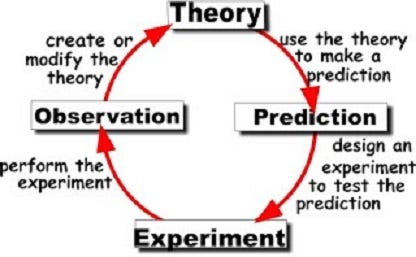

Yet David Chalmers himself does seem to be committed to the “principle of sufficient reason” in that he believes that his hard question about the physical/brain-consciousness relation can (or must) be answered — even if only “in principle” (or in the future). However, Chalmers doesn’t believe that this is the case with all questions.

For example, Chalmers seems to reject this question:

Why is there matter, space-time, gravity, etc. in the first place?

Or, in Chalmers’ own words, he tells us that

“(n)othing in physics tells us why there is matter in the first place, but we do not count this against theories of matter”.

That means that Chalmers himself may accept an end to questions (hard or soft) when it comes to what he calls “the fundamentals of physical theory”. That is, he argues that the question of “why there is matter in the first place” may well be illegitimate — at least from a position within physics (i.e., it may be — or is — a fit subject for philosophy or theology).

In the same vein, can’t we reject the need to see the laws of physics or the constants of nature (which underpin spacetime, matter, gravity, etc.) as having either a necessary or accidental (or contingent) nature? More importantly, can’t we question the assumption that these questions can be answered? In other words, the following question may be bogus:

Why are the laws of physics (or constants of nature) the way they are rather than another way?

Thus, just as physics “does not tell us why there is [matter] in the first place”, so it may not be able to tell us why the laws of physics are the way they are. (Or, alternatively, physics can’t — or doesn’t — tell us why the constants have the values which they do have.)

So David Chalmers’ position (which is the same as most physicists) is that we must begin with the fundamental laws and constants of nature. Such things are deemed primitive. That is, they can’t be “deduced from more basic principles”. This means that Chalmers has a position on physics that seems to go against his own hard question on the nature of consciousness (or experience).

Having said all that, Chalmers does indeed concede the possibly that an “epistemically primitive connection between physical states and consciousness” may be a “fundamental law”. So doesn’t that basically mean that we can’t (or simply may not) be able to explain that connection between the physical and consciousness? Perhaps there’s literally nothing to explain because of its very primitiveness.

Alternatively, is this ostensible lack of an explanation of the physical-consciousness relation a result of the fact that (according to the philosopher John Heil) “our mental and physical concepts are too far apart to be unified under a single theory”? Perhaps the mind-body (or body-mind) relation is just too simple, fundamental or basic to be explained by any theory — mental or physical. Perhaps there’s literally nothing to explain. Indeed isn’t this one of the definitions of the words ‘brute fact’?

Brute Facts?

John Heil goes on to say:

“Once you reach a basic level, however, explanation runs out: things behave as they do because they are as they are, and things with this nature just do behave in this way. Explanation works, not because all explanation is traceable to self-explaining explainers. Explanation works by reducing the complex to the less complex. At the basic level the behaviour of objects cannot be further explained.”

Indeed when physical explanations do come to an end, then we reach a point when

“things behave as they do because they are as they are, and things with this nature just do behave in this way”.

That is, we can’t explain or ask questions anymore. However, it’s of course the case that nothing can stop us from asking these questions — even if they are unanswerable.

In terms of brute facts again.

The acceptance of brute facts in physics may not help us when it comes to the nature of the brain-consciousness relation. The Australian philosopher J.J.C. Smart, for example, argued against the acceptability of this analogy. In his ‘Sensations and Brain Processes’ (1959), he wrote:

“It is sometimes asked, ‘Why can’t there be psycho-physical laws which are of a novel sort, just as the laws of electricity and magnetism were novelties from the standpoint of Newtonian mechanics?’ Certainly we are pretty sure in the future to come across ultimate laws of a novel type, but I expect them to relate simple constituents… I cannot believe that the ultimate laws of nature could relate simple constituents to configurations consisting of billions of neurons (and goodness knows how many billions of billions of ultimate particles) all put together for all the word as though their main purpose was to be a negative feedback mechanism of a complicated sort.”

In other words, the arrival (or emergence?) of consciousness would be required to be a relation not between the very simple and the (slightly) less simple; but between the hugely complex (i.e., the brain or its individual parts) and the simple (i.e., a conscious state).

Heil offers a similar argument about the possibility of brute fact(s) when it comes to the physical-consciousness relation. Though, whereas J.J.C. Smart states a relation between the brain’s complexity and a simple mental state/experience; Heil makes a connection between a complex brain state and a “complex qualitative experience”. Heil writes:

“This alleged brute fact differs from brute facts concerning electrons because it connects something complex — a qualitative experience — with something very complex — a brain process, for instance, involving millions (billions?) of particles.”

To conclude. Heil again questions the status of what we may call the Brute Fact Theory of Consciousness:

“Perhaps there are such brute facts, but if there are, they are very different from the kinds of brute fact we expect to find in mapping the nature of the material world.”

If they are different (let alone very different), then what right have we to make comparisons between the ostensible physical-consciousness brute fact and those found by particle (or quantum) physicists?

David Chalmers and Christof Koch

Chalmers, on the other hand, does reject any physical-to-consciousness brute fact. In other words, he believes that there are questions about this relation which need to be answered. More technically, Chalmers says that

“Crick and Koch’s theory gains its purchase by assuming a connection between binding and experience, and so can do nothing to explain that link”.

So let’s reformulate Chalmers’ words as a simple question:

What is the connection (or link) between binding and experience?

What does Chalmers mean by the word “explain” (as used in the quote above)? What kind of explanation would make him happy? Is there even a possible (or hypothetical) explanation which could be conjured up (care-of speculative philosophy or metaphysics) which would make him happy or satisfied? Let’s think about it. Think about any possible arguments (or data) which could explain the link between the physical and experience. What would they look like? What could they look like?

Chalmers — elsewhere — makes much of “conceivability” leading to “metaphysical possibility”. This means that if we can conceive of such a link between the physical and experience, then that link would be metaphysically possible. So, go ahead, conceive of such a link. What, precisely, have you conceived?

Does Chalmers (kind of) admit that such a link can’t be found because it can’t even be conceived of in the first place? It’s hard to say. However, he does quote Christof Koch when he said the following:

“‘Well, let’s first forget about the really difficult aspects, like subjective feelings, for they may not have a scientific solution.’”

It’s true here that Koch refers to a “scientific solution” — not a philosophical or metaphysical one. However, would a philosophical or metaphysical solution be any more forthcoming than a scientific one? What would it look like?

So is the question

Why do the oscillations give rise to experience?

even a good question? Is there an answer to this — even in principle? What kind of answer is Chalmers looking for? He isn’t asking the following question:

How do oscillations in the brain give rise to experience?

That question could be answered in physical or causal terms. Though this too is problematic in that, for a start, we’d need to be clear about the word ‘how’. In addition, don’t (at least some) how-answers presuppose (at least some) why-questions? Similarly, don’t (at least some) why-questions also presuppose (at least some) how-answers?

As for Chalmers’ own why-question (rather than his how-question), perhaps there isn’t an answer.

More Hard Questions?

To help matters here, let’s tackle some questions which can’t be answered. For example, take this question:

Why is water H₂0?

That is really the same as this question:

Why is H₂0 actually H₂O? (Or: Why is water actually water?)

However, that’s not true of this Chalmers-like question:

In terms of causality, we can’t ask

Why does a collection of H₂0 molecules cause (or bring about) water?

because they’re one and the same thing. However, a question can be asked about the physical bringing about — or causing — the mental. Then again, take this different kind of question about water:

Why is water H₂0 and not something else?

This question may be bogus. That is, we can now reply:

If water were something else (say, the fictional O₃Z), then it wouldn’t be water at all.

Then again, the phenomenal properties of O₃Z could be the same as water; though it wouldn’t be water as it’s scientifically known to us. (Though what if water’s phenomenal properties matter — or matter more — than molecular structure? Why is molecular structure always paramount?)

In addition, what if one is an identity theorist? Or what if one is a conceptual pluralist and ontological monist who believes that the mental and the physical are two aspects of the same substance? Then the question

Why does the physical bring about (or cause) the mental?

would be as nonsensical as asking

Why does H₂O bring about (or cause) water?

Conclusion

So, to summarize. When Chalmers asks,

“Why do the oscillations give rise to experience?”

we can reply:

Why does anything give rise to experience?

Indeed it can be said that whatever someone posits as an explanation or an answer, Chalmers could ask the very same question. Could a neuroscientist, physicist or philosopher cite any fact about the physical (or the brain) which would make Chalmers happy? In other words, Chalmers can ask his question no matter what anyone says about the brain or the physical and its relation to consciousness/experience.

Therefore the question

Why does physical x give rise to experience?

can always be asked. Indeed Chalmers may keep on asking his Hard Question.