Way back in 1979, controversial philosopher Richard Rorty discussed panpsychism at a time when it was completely ignored by virtually all analytic philosophers.

Way back in 1979 (i.e., before the “rise of panpsychism”), the controversial American philosopher Richard Rorty (1931- 2007) discussed neutral monism and panpsychism at a time when these particular philosophical isms were completely ignored by virtually all analytic philosophers. (Rorty discussed neutral monism and panpsychism in his well-known book, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature.)

Perhaps that general ignoring of neutral monism and panpsychism may explain why Rorty himself spent so little time on them. Yet, despite that, Rorty did still get to the heart of the problem in the very few words he did offer us.

[See the 20th-century history of panpsychism here and my own ‘The Recent Rise of Analytic Panpsychism: 1996 to 2022’.]

Rorty gets to the heart of the problem with the intrinsic properties which panpsychists posit:

Nothing can be said about them.

Indeed even if such a (in the singular) intrinsic property is deemed to be consciousness (or experience/phenomenal properties), once consciousness is completely divorced from human and animal subjects and their material constitutions, behaviours, etc., and indeed from all specific entities or things, then (again) nothing (much) can be said about it.

More relevantly, Rorty asked about the lack of (to use his own words) “powers or properties” (which is a kind of epiphenomenalist point) of the intrinsic properties of panpsychists. Indeed this is precisely the main problem which physicists and other scientists point out when they spare the time to discuss panpsychism.

It must now be said that Richard Rorty primarily discussed neutral monism, not panpsychism.

Russell’s Neutral Monism and Panpsychism

Of course neutral monism and panpsychism are very closely linked. Indeed, in the case of at least some philosophers, they’re almost identical.

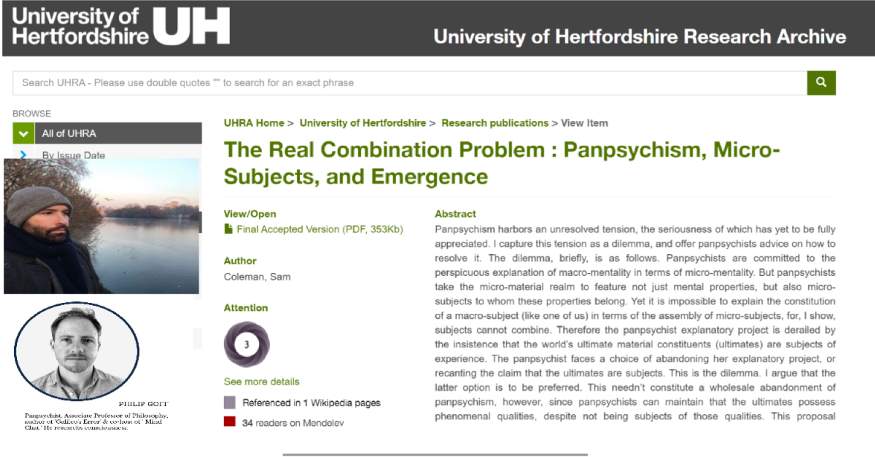

Take the the dispute between the philosophers Philip Goff and Sam Coleman.

The panpsychist Philip Goff is much beholden to neutral monism (as he has often freely admitted — see here and here). Yet, as ever with the shifting minutia of the technical terms of analytic philosophy, all this is complicated by the fact that Goff’s position can also be deemed to be a kind of Russellian monism. What’s more, Sam Coleman’s own position can be deemed to be a kind of panpsychism! (Coleman states that his position “needn’t constitute a wholesale abandonment of panpsychism”.)

This means that what will be deemed to be important and fundamental distinctions (by at least ten people) from deep inside this academic debate, won’t actually seem that way when looked at from the outside. As a consequence of this, it’s probably best to see Goff as being a (as it were) pure panpsychist and Coleman as being a Russellian monist — and that’s despite the many crossovers and grey areas between their positions. Indeed Goff is best seen as a panpsychist for the simple reason that his position squares very well with most accepted conceptions — if there even are such things! — of panpsychism. And that’s not to forget that Goff classes himself as a panpsychist.

[See Coleman’s ‘The Real Combination Problem : Panpsychism, Micro-Subjects, and Emergence’.]

In any case, one of the main points which unites contemporary panpsychists with Bertrand Russell isn’t only the latter’s commitment (at least at one point in his career) to a basic monistic stuff, but also his commitment to the “fundamentality” of experience — or, to use Russell’s own technical term, “percepts”.

To all these philosophers, nothing is more (as it were) Given than experience, consciousness or percepts. Thus these philosophers argue that experience is surely where we must start. (As David Chalmers put it: “Experience is a datum in its own right.”)

Of course the contemporary panpsychists who’ve been inspired by Russell’s neutral monism (or by Russellian monism) don’t argue that their own (in the plural) panpsychisms and neutral monism are identical in every detail.

Take Russell’s stress on “events” (i.e., rather than on consciousness, experience, etc.).

This stress on events puts Russell a little at odds with most contemporary panpsychists. For example, Russell said that his neutral monism is a monism

“in the sense that it regards the world as composed of only one kind of stuff, namely events”.

He then argued that “it is [a] pluralism in the sense that it admits the existence of a great multiplicity of events”.

And since the intrinsic-properties-cannot-be-described position is being discussed here, it’s now worth stating that Russell himself argued that we have no access — either observationally or otherwise — to the “intrinsic characteristics” of electrons, spacetime, rocks, etc. Instead, “[w]hat we know about them” is simply “their structure and their mathematical laws”.

In addition and on Russell’s reading, mathematical physics only deals with structures, behaviour and relations/interactions; not with intrinsic properties. Another way of putting that is to argue (as Russell himself argued) that whatever is stated in mathematical physics, none of it is about anything intrinsic (at least as the intrinsic is seen by panpsychist philosophers).

All that said, Russell did have a problem with the (mainly scientific) rejection of intrinsic properties.

In basic terms, Russell argued that it simply can’t be a question of (not his own words) “structures and relations all the way down”. Russell himself put it this way:

“There are many possible ways of turning some things hitherto regarded as ‘real’ into mere laws concerning the other things. Obviously there must be a limit to this process, or else all the things in the world will merely be each other’s washing.”

Despite the words above, Russell also expressed what can be called a Kantian stance on these issues when he stated that all we have is the “effects of a thing-in-itself”. Thus Russell came to the conclusion that if we only have access to effects (perhaps equivalent to Kant’s “phenomena”), then why not factor out the distinction between intrinsic properties and their effects (i.e., external properties) altogether? In other words, what’s left of intrinsic properties after all these qualifications?

Now let’s return to Richard Rorty.

Fundamentality?

Rorty began his discussion with the following words:

“[N]eutral monism, in which the mental and the physical are seen as two ‘aspects’ of some underlying reality which need not be described further.”

In both philosophy and physics, many different things have been described as being “fundamental”. (In logic too, modus ponens can be deemed to be fundamental — see here.) And precisely because of such fundamentality, any x which is deemed to be fundamental (to use Rorty’s words) “need not be described further”.

Take the Australian philosopher David Chalmers’ position on the fundamentality of consciousness. This is how Barbara McKenna tells Chalmers’ story:

“Over the millennia scientists have concluded that there are a handful of elemental, irreducible ingredients in the universe — space, time, and mass, among them. At a national conference in 1994, philosopher David Chalmers proposed that consciousness also belongs on the list.”

And, on behalf of the (as it were) ineffable nature of whichever x is taken to be fundamental at any given time in the history of philosophy, the philosopher John Heil (1943-) had this to say on fundamentality itself:

“Once you reach a basic level, however, explanation runs out: things behave as they do because they are as they are, and things with this nature just do behave in this way. Explanation works, not because all explanation is traceable to self-explaining explainers. Explanation works by reducing the complex to the less complex. At the basic level the behaviour of objects cannot be further explained.”

Indeed when physical explanations do come to an end, then we reach a point when

“things behave as they do because they are as they are, and things with this nature just do behave in this way”.

Depending on what any fundamental x is taken to be, philosophers will put these points in different ways. That is, they won’t be as open and explicit so as to say that x (to quote Rorty) “need not be described further”. That said, they often do state virtually the same thing as Rorty — just in different words.

Another important point is that all the things which have been taken to be fundamental (at many different times) are certainly not on a par. One obvious example of this is that the fundamental entities of physics are worlds apart from the fundamental entities of philosophy. Thus, to be even more specific, taking quarks or spacetime to be fundamental is very different to taking intrinsic properties (or, indeed, the World Soul, Love, monads, God, etc.) to be fundamental — and for many obvious reasons.

Different Reasons to Embrace Intrinsic Properties

Rorty continued:

“Sometimes we are told that this reality is intuited (Bergson) or is identical with the raw material of sensation (Russell, Ayer), but sometime it is simply postulated as the only means of avoiding epistemological skepticism (James, Dewey).”

The closest Rorty came to stating the position of contemporary panpsychists is when he expressed (again) Bertrand Russell’s position. In that position, the “raw material of sensation” constitutes the stuff of neutral monism.

The positions advanced by William James and John Dewey (at least as expressed by Rorty), on the other hand, immediately reminded me of Philip Goff’s and other contemporary panpsychists’ positions. Such philosophers also believe that intrinsic properties — and indeed panpsychism itself — are “postulated as the only means of avoiding epistemological skepticism” regarding consciousness and the relation between mind and matter. Thus panpsychism and its intrinsic properties are also deemed to be (as it’s often put) “elegant and parsimonious”. Another way of putting this is to say that panpsychism and its intrinsic properties are a neat and tidy possible solution to the problem of consciousness — particularly to the (with Germanic capitals) Hard Problem of Consciousness. Thus panpsychism and its intrinsic properties are a parsimonious and elegant way to avoid epistemological scepticism by virtue of their unification of matter and mind…

Yet all this is at a huge cost.

What’s more, it’s debatable whether or not anything is truly avoided by panpsychism.

Thomas Nagel on What It is Like

Richard Rorty doesn’t mention the American philosopher Thomas Nagel (1937-) explicitly when he uses the ironic phrase “we just know what it’s like”. However, elsewhere in Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature Rorty did write the following words about the aforementioned (near) merging of panpsychism and neutral monism:

“A panpsychist view is also suggested by Thomas Nagel’s for an ‘objective phenomenology’ which would ‘permit questions about the physical basis of experience to assume a more intelligible form’ (‘What Is It Like to Be a Bat?’) [] However, in both Hartsthorne and Nagel, panpsychism tends to merge with neutral monism.”

In any case, Rorty got to the heart of the problem in this passage:

“In no case are we told anything about it [“this reality”] save that ‘we just know what it’s like’ or that reason (i.e., the need to avoid philosophical dilemmas) requires it.”

In addition:

“But in fact the ‘neutral stuff’ which is neither mental nor physical is not found to have powers or properties of its own, but simply postulated and then forgotten about (or, what comes to the same thing, assigned the role of ineffable datum).”

Here Rorty ties neutral monism — or panpsychism — to Nagel’s “what it is like to be a bat” thesis.

So we may well know what these intrinsic properties are like in the case of our own mental states. However, the intrinsic properties of panpsychists are supposed to be instantiated by rocks, cells, electrons, spacetime, etc. too! Thus if there is something it is like for them, then how could we know that? In other words, what about the ineffable data of all other beings and entities?