In the last twenty years (or even longer), philosophical zombies have been very popular in philosophy. The exotic and sexy appeal of “p-zombies” has even spread to those people who don’t usually care about philosophy or (particularly) consciousness. So has far too much time been spent on entities which are, after all, only meant to be (even by their adherents) logical possibilities?

So what is a philosophical zombie? This is one account:

“A philosophical zombie or p-zombie is a hypothetical being that is physically identical to and indistinguishable from a normal person but does not have conscious experience, qualia, or sentience. [] Proponents of philosophical zombie arguments, such as the philosopher David Chalmers argue that since a philosophical zombie is by definition physically identical to a conscious person, even its logical possibility would refute physicalism, because it would establish the existence of conscious experience as a further fact.”

The Australian philosopher David Chalmers (1966-) argues that it’s logically possible that philosophical zombies could exist.

So what does this claim amount to?

Does it amount to much and should we spend much (or even any) time on it?

Essentially, much (or all) zombie-talk involves philosophical thought experiments. Such thought experiments can irritate people — even some philosophers. That said, thought experiments certainly serve some purpose.

Thought experiments have certainly been very important in theoretical physics. However, many historical thought experiments in physics later came to be backed up by experiments/tests, confirmed predictions and/or actual observations. Yet this certainly hasn’t been the case when it comes to most (or even all) philosophical thought experiments. Such experiments, almost by definition, can never be confirmed or disconfirmed. Indeed, they seem to be designed to have no (ironically) experimental, testable or observational element to them.

And all that is certainly true of thought experiments about philosophical zombies.

In that respect, then, perhaps the well-known and ironic question

“How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?”

is just as acceptable as — at least some — philosophical thought experiments.

So, as just stated, many people are bemused — and sometimes annoyed — by the various zombie scenarios. Perhaps that’s because they believe that such scenarios involve natural or metaphysical claims; whereas, in fact, they’re often only about logical possibility.

That basically means that they’re only about possibilities — not actualities or realities. That said, most people already know that there are no zombies in this world. Thus, the purely logical nature of these thought experiments should already be apparent…

Yet these zombie scenarios are about much more than mere logical possibility. They’re also about logical possibility leading in all sorts of other non-logical and (apparently) important directions.

Almost Everything is Possible

The English philosopher Bertrand Russell (1872–1970), in his The Problems of Philosophy, wrote the following words about another well-known logical possibility:

“No logical absurdity results from the hypothesis that the world consists of nothing but myself [] and that everything else is mere fancy. But although this is not logically impossible, there is no reason whatever to suppose that it is true; and it is, in fact, a less simple hypothesis, viewed as a means of accounting for the facts of our own life, than the commonsense hypothesis that there really are objects independent of us, whose action on us causes our sensations.”

When I woke up this morning, it was logically possible that I was still asleep. And when I moved over to the tap, it was logically possible that poison (not water) could have come out of the tap. (If it were only water, then it was still logically possible that I might have choked on it.) Then I looked out of the window, and it was logically possible that the town I saw in front of me was a projected simulation of what I’d seen the day before. And so on and so on and so on.

Despite these over-the-top (or simply silly) scenarios, David Chalmers believes that p-zombies are worth discussing because (to use his own words) “there seems to be no a priori contradiction in the idea” of them. Yet there’s also no a priori contradiction in a human being having 107 legs. However, such a possibility won’t really tell us much — at least not outside human biology and anatomy.

Well, Chalmers believes that it’s not just about the bare possibility that philosophical zombies could exist. It’s that this possibility can tell us something about consciousness, and, perhaps, much else too.

In more detail. Chalmers argues that we can conceive of a physical system that’s note-for-note identical to a normal human being, but which doesn’t instantiate consciousness. Such as system would therefore be a philosophical zombie.

Alternatively, it may be a “zombie-invert” in that some of its experiences (usually those of colour) could be inversions of those of a normal human being. Yet the invert-zombie still has the same nuts and bolts as a normal human being. However, it/she/he has different experiences.

So the zombie-invert is still allowed his/her/its experiences.

There’s also a partial zombie who/which also instantiates experiences. However, it/she/he doesn’t have as many experiences as normal human beings. (Perhaps he/she/it can only feel pain or experience orgasms.)

The point is that all these zombies are physically identical to normal human beings from the third-person point of view. That is, the behaviour and physical constitution of p-zombies is indistinguishable from that of normal human beings.

So what about the first-person point of view of such zombies?

In other words, “what is it like” to be a philosophical zombie?

Well, there’s nothing it’s like to be such a zombie! (Except, of course, in the partial and inverted zombie cases.)

On a larger scale. What about a physically identical universe which doesn’t give rise to consciousness, though which does give rise to p-zombies? Can we therefore argue that such zombies are (to use Chalmers’ words) “naturally possible” (see here)? That said, the usual argument against this particular scenario is that according to our own laws of nature, such p-zombies (probably?) couldn’t exist. That is, given identical physical, bodily and environmental facts, then such a universe couldn’t help but give rise to consciousness. (All these subjects have been debated to death by analytic philosophers, so I won’t even attempt to add anything here.)

So what is the actual link between possibility and actuality?

Chalmers — for one — never really discusses coming across real (or actual) p-zombies because the whole point of his thesis hinges on the importance of simply and purely conceiving of them. He’s also keen to show us how that very conceiving establishes certain other(!) philosophical positions. In the main case, then, one other philosophical position is that consciousness (or experience) is over and above everything physical and functional. In other words, even though this conceived of (or even real) p-zombie behaves and looks just like a normal human being, it still may not (or does not) instantiate consciousness at all. This means that, for all intents and purposes, a p-zombie is a (as it were) robot or machine in human clothing.

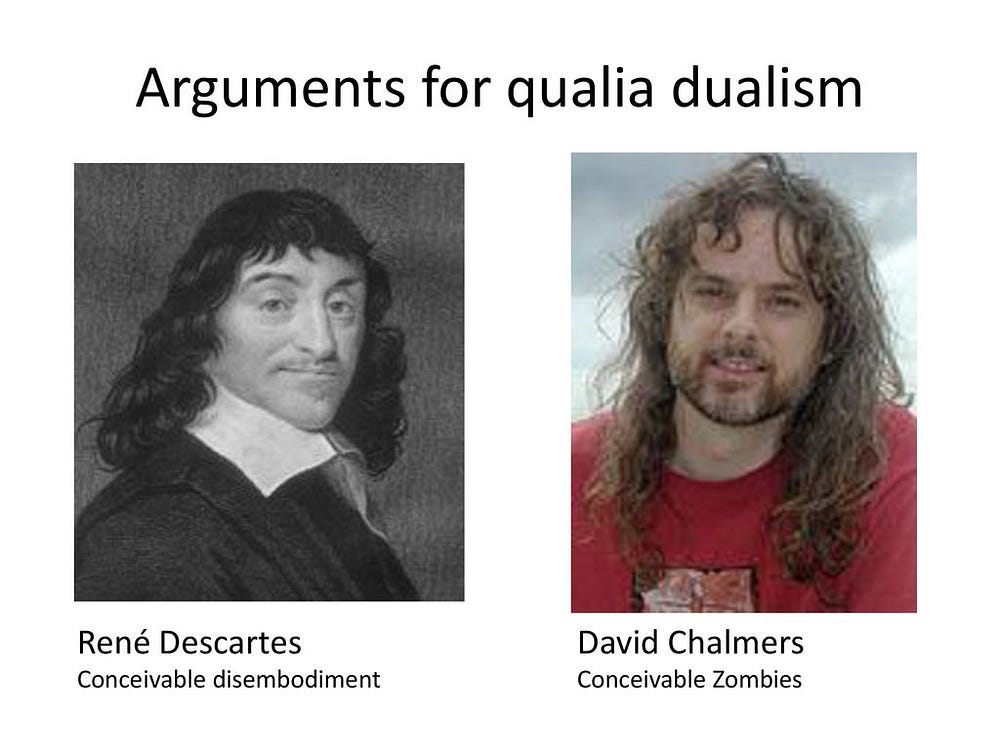

In broader terms, thought experiments about philosophical zombies stem from the philosophical, logical and psychological move from conceivability to possibility (as with Descartes’ reliance on his own conceivings — see here). So these notions shall now be tackled.

The Arguments

Clearly, possibilities can be a thousand miles away from actualities. Indeed, the zombie scenario appears to be a good example of this. However, Chalmers believes (as already stated) that p-zombies tell us something about the limits of physicalism.

In more detail, p-zombies are (in Chalmers’ own words) “microphysically identical to us without consciousness”. Thus:

(i) If zombies are physically and behaviourally identical to normal human beings,

(ii) then consciousness must be something over and above the physical.

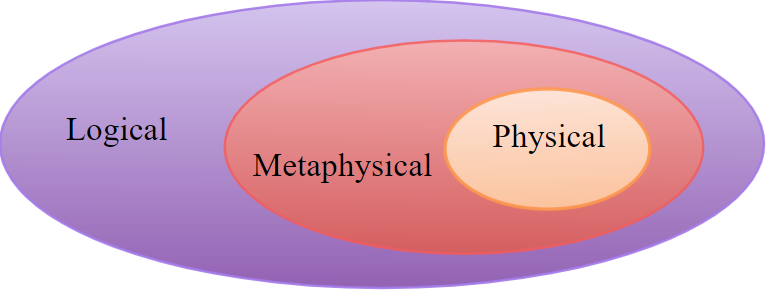

In addition, Chalmers explains this disjunction between logical possibility and actuality (in relation to qualia) in the following ways.

Firstly, Chalmers argues that absent qualia and inverted qualia are “logically possible”. However, they’re still “empirically and nomologically impossible”. In terms of science and the problem of consciousness, it can be intuitively said that if any given x is both empirically and nomologically impossible, then why should we care that it’s still also logically possible? What do we gain (scientifically, and, perhaps, philosophically) from thinking about scenarios which involve logical possibility, yet, at the very same time, also involve empirical and nomological impossibility?

In any case, if there could be an identical universe to our own which didn’t give birth to consciousness, then, Chalmers concludes, consciousness must be something above and beyond the physical.

So this is where conceivability and metaphysical possibility will be discussed in detail.

Zombies and Conceivability

Conceivability and possibility are central to David Chalmers’ work on zombies, panpsychism, physicalism, and all sorts of other stuff too. More relevantly, conceivability-leading-to-metaphysical-possibility is central to much of Chalmers’ work.

Chalmers states that “a claim is conceivable when it is not ruled out a priori”.

However, there are an indefinite (even infinite?) number of states of affairs (or claims) which can’t be ruled out a priori. Even the existence of sharks with legs or mushrooms with a sense of humour can’t be ruled out a priori. In other words, the only things which can be ruled out a priori are claims or states of affairs which break known logical laws or which contain contradictions. Thus, the (as it were) conceivable universe is highly populated with strange and bizarre entities, conditions, events, etc.

To put some meat on all this. Chalmers offers his own example of the conceivable. He tells us that it’s “conceivable that there are mile-high unicycles”. So what are we supposed to conclude (or philosophically achieve) by saying that mile-high unicycles are conceivable and therefore possible? Where does it take us?

In detail, Chalmers argues:

(i) If we can conceive of zombies in our world (or at other worlds),

(ii) then zombies are metaphysically possible.

Chalmers (in his own words) supports his conceivability argument by arguing thus:

“If P & -Q is conceivable, [then] P & -Q is metaphysically possible [as well as being] supported by general reasoning.”

Is there such a link between conceivability and possibility? If there is, then what kind of link is it?

Is that link itself grounded in conceivability, possibility or both?

Chalmers codifies all this with a logical argument:

i) It is conceivable that P & not-Q.

ii) If it is conceivable that P & not-Q, then it is metaphysically possible that P and not-Q.

iii) If it is metaphysically possible that P & not-Q, then materialism is false.

iv) So materialism is false.

In the above, Chalmers’ slide here from conceivability to metaphysical possibility can easily be seen.

The argument above can be made even clearer (as well as more blatant or obvious) in the following way:

i) Can we conceive of a round square? No.

ii) Then a round square isn’t metaphysically possible.

iii) Can we conceive of a man with 105 legs? Yes.

iv) Then a man with 105 legs is metaphysically possible.

Yet, again, what are we supposed to philosophically gain (or achieve) by saying that x or y are conceivable and therefore possible? Where does it take us?

In any case, logical possibility excites philosophers like Chalmers. So should readers conclude in the same way as Bertrand Russell above? That is, should readers state the following? -

Even though x (or a zombie) is not logically impossible, then there is still no reason to suppose that claims about x are true or that x is real or can be instantiated.

Put simply: something that’s logically possible may not be actual (or the case). Indeed, what’s logically possible is often not the case. So why contemplate the logically possible at all — even in philosophy? Where will it get us?

***********************

Part Two: The Psychology of Conceiving

How could a philosopher or anyone else (in a strict sense) know that he’d conceived of a philosophical zombie? What if some readers of these words can’t conceive of a phil-zombie — even if other people can do so? And even if some readers of these words can (seemingly) conceive of a p-zombie, then how could other people know that they’d done so? Indeed wouldn’t the best philosophical policy be to accept (or believe) that such people hadn’t actually conceived of a p-zombie?

Moreover, isn’t the very notion of conceiving of any given x far too psychologistic (or mentalistic) an idea to be sustaining metaphysical theses? What’s more, if other minds are a philosophical “problem”, then other minds conceiving of p-zombies (or anything else for that matter) is a problem within an already-existing problem.

More concretely, if any readers of these words actually came across an entity which acted and looked — in every single detail — like an ordinary human being (which is the whole point of the p-zombie thought experiment), then how could they extract from all this that it may, in fact, be a p-zombie? In addition, if such readers ever did come across a p-zombie which acted and looked just like them, then surely the obvious conclusion would be that it instantiated consciousness (or experiences) just like them. In other words, wouldn’t these people simply assume that this “zombie” (or x) felt pain, sometimes gets angry, could smell garlic, etc?

It can also be asked if when Mary supposedly conceives of a p-zombie, then how does it differ from her conceiving of her mother, father or her best friend? After all, when she conceives of any of the latter three, she can’t literally conceive of his/her consciousness or of his/her actually being conscious. Instead, all she’s got to go on is the physical and verbal behaviour of her mother, father or best friend. And that’s also true of p-zombies.

So perhaps that’s Chalmers’ point!

If it is Chalmers’ point, then let’s spell it out again.

Conceiving of a p-zombie is no different from conceiving of your mother, father or best friend.

Again, perhaps that’s partly why Chalmers believes conceiving of a p-zombie is possible. And if conceiving of p-zombie is possible, then its actual existence must also be (metaphysically) possible.

But does all that actually work?

When people conceive of a p-zombie (just as when people conceive of their mothers, fathers or best friends), perhaps they don’t conceive of an entity (or being) actually lacking consciousness. Perhaps that’s because such a thing can’t be conceived of in the first place. Yet the argument is that a person is supposed to be capable of conceiving of a being (or entity) behaving like his mother, father or best friend — though which doesn’t instantiate consciousness. However, how is that different to that very same person conceiving of his mother, father or best friend? And perhaps it’s no different because he can neither conceive of the consciousness of a fellow human being nor of a p-zombie.

Basically, then, consciousness is (as it were) known because it’s behaviourally or physically expressed. Unexpressed consciousness, on the other hand, is not conceivable. This means that it’s just as hard to conceive of another being’s consciousness as it is to conceive of its lack of consciousness (or vice versa).

Despite all the above, can the contrary ever be categorically stated?

That is, can it really be argued that no one could ever conceive of a p-zombie (or a “p-zombie world”)? In other words, if Chalmers, etc. can’t categorically claim that they have conceived of a p-zombie, then perhaps we can’t categorically claim that they haven’t done so. How could you, I or anyone else know that Chalmers hasn’t conceived of a p-zombie or anything else? Consequently, this may mean that all the sceptical questions aimed at such conceivings can now be aimed at the sceptics about such conceivings.

Yet that last conclusion surely demonstrates the central point of this issue.

That point being that since we’re talking about mentalistic (or psychological) conceivings, then whether or not subject S has truly conceived of a p-zombie can never be established. And if it can never be established, then how can such conceivings provide the basis of a philosophical thesis?

So, again, what is it to conceive of a philosophical zombie? What is the mental or abstract (mental) content of such an act of conceiving?

The American philosopher Daniel Dennett has also discussed all of this.

Daniel Dennett’s Zimbo

Dennett (1942-) has a big problem with David Chalmers’ philosophical zombies.

Specifically, Dennett, too, focusses on the notion of conceiving. (He does so in the ‘Zombies and Zimboes’ chapter of his book, Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking.)

For Dennett, the main point of what he calls a ‘zimbo’ is that there’s no way of knowing if it/she/he instantiates — or doesn’t instantiate — experiences or consciousness. And if there’s no way of knowing that (at least according to Dennett’s behaviourist and verificationist position), then why deny less to the zimbo than one would do so to a normal human being?

There’s a problem here.

If Dennett’s zimbo were literally identical — in every respect — to a normal human being, then how could we say that there’s either something less — or, indeed, something more — to it/him/her? And that’s because we could never know that we were actually confronting a zimbo. That said, this is part of the very point of Dennett’s thought experiment: a thought experiment which is itself a response to other philosophers’ thought experiments.

Dennett puts it this way:

“When people say they can conceive of (philosophical) zombies, we are entitled to ask them how they know. Conceiving is not easy!”

More particularly, how does a dualist, anti-physicalist or anyone else know that he’s conceived of a philosophical zombie? How do the readers of these words know that such a person has conceived of a philosophical zombie? In addition, how does any conceiver-of-a-zombie (to use Michael Dummett’s term) “manifest” his act of conceiving to others? What if it’s a thoroughly private act? And, if it is private, then what status could it possibly have when it comes to establishing a metaphysical position or thesis?

We can get even more fundamental here:

What is it to conceive of… anything?

This isn’t to argue that people don’t conceive of things. (They obviously do.) It’s just a demand for some kind of account of the act of conceiving-of-a-zombie.

In any case, Dennett gave some examples of things which he believes are difficult to conceive. He writes:

“Can you conceive of more than three dimensions? The curvature of space? Quantum entanglement?”

The least that can be said here is that Dennett’s examples are all very different.

So perhaps we can’t actually imagine (or, more literally, picture) more than three dimensions, the curvature of space and quantum entanglement. However, can we conceive of them?

Dennett continues:

“Just imagining something is not enough — and, in fact, Descartes tells us, it is not conceiving at all.”

The thing is that the existence of more than three dimensions, the curvature of space and quantum entanglement surely must have been conceived of — many times — because they’re accepted notions in physics. Indeed they’re even accepted aspects of the physical world (or at least two of them are). That is, no one has ever seen or observed these things. And, depending on definitions, not one has ever imagined these things either. So all we have left is to conceive of more than three dimensions, the curvature of space and quantum entanglement.

Thus, Descartes and Chalmers may be onto something here!

Yet even here conceiving of these things may be in a different logical space to conceiving of a philosophical zombie. After all, there are a lot of equations, natural laws, theories, indirect/direct observations, experiments, tests, etc. to account for the curvature of space and quantum entanglement (if not extra dimensions).

So are there a lot of equations, natural laws, theories, experiments, tests, indirect/direct observations, etc. to account for philosophical zombies? It can be supposed, however, that someone like David Chalmers wouldn’t claim that there are…

After all, philosophical zombies are only a possibility.

No comments:

Post a Comment