Philosopher Bernardo Kastrup believes that psychedelic experiences run free of the brain. And that’s because the trippers who have them are tapping into Cosmic Consciousness.

“There is something very wrong with this story that brain activity generates conscious experience.”

— Bernardo Kastrup’s last words in his video presentation.

The Dutch computer scientist and philosopher Bernardo Kastrup’s central thesis is that human consciousness (or experience) doesn’t require the physical and biological brain. Indeed that thesis is the backdrop to his scientific claim that during psychedelic experiences there is less brain activity than during (as it were) normal (or waking) conscious states. The conclusion being that such psychedelic experiences — and indeed all conscious experience — must ultimately run free of the brain.

So, in order to establish this radical position, doesn’t Kastrup need to establish zero brain activity during psychedelic experiences?

An important corollary to Kastrup’s ideas is that because the brains of the subjects of psychedelic experience are not relying on the brain for their experiences, then they must be relying on something else. And that something else is (to use Platonic capitals) Cosmic Consciousness (sometimes called Universal Consciousness). That is, Cosmic Consciousness is responsible for the (as Kastrup puts it) “richness” of psychedelic experience.

However, in the video which is the basis of this essay, Kastrup doesn’t put his position quite so simply and/or explicitly. Indeed, his presentation is replete with technical terms, images, graphs and much academic hedging. Yet he most certainly does put his broad philosophical position simply (i.e., as it relates to psychedelic experiences and much else) elsewhere.

(For example, see Kastrup’s blog post here in which he tells us that he has “cultivated psychedelic-containing organisms at home” and that the “experiences they provided me with years ago have been of tremendous learning value and considerably helped [his] personal development”.)

The Video Presentation

The featured video: ‘Dr. Bernardo Kastrup: what neuroscience actually shows about consciousness’.

Bernardo Kastrup isn’t a neuroscientist. Yet in the video featured in this essay he spends much time on the (as it were) hard data of neuroscience. Indeed, it’s obvious that Kastrup wants to make it crystal clear to everyone that he knows much neuroscience back-to-front and in great detail — hence his many uses of technical terms from neuroscience, his use of graphs, brain imagery and his almost — deliberately? — impenetrable academic detail.

In other words, is Kastrup fudging the philosophical issue with largely irrelevant and often trivial neuroscientific detail?

All this is the very-hard “data” on which Kastrup’s “analytic idealism” (or Cosmic Idealism) is supposedly based. And this is also how Kastrup hopes to differentiate his own brand of idealism from all the other brands on sale in the commercial marketplace (e.g., the book companies which publish philosophy). Indeed, Kastrup is explicit about his scientific idealism in various places.

For example, the following is an Essentia Foundation entry (probably written by Kastrup himself) for “analytic idealism”:

“[Analytic idealism] is a formulation that will appeal to intellectually hard-nosed, left-brained, science-oriented people [].”

In the video focussed upon in this essay, Kastrup particularly cites (what he calls the) “multiple papers” which he believes back up his position. Yet do these papers really back up Kastrup’s philosophical position? And do even their scientific claims perfectly square with Kastrup’s? Alternatively, is Kastrup simply interpreting the scientific data though the lens of his philosophical and spiritual idealism?.

(The words “spiritual” and “religious” have just been used. They aren’t rhetoric or whatever. They’re used because Kastrup himself frequently uses such words — see here, here, here and here - about his own position. Indeed, it’s difficult to interpret Kastrup’s overall philosophy in any other way.)

More particularly and as a result of the above, Kastrup spends more time in this particular video on what he calls the “abundant strong correlations” between brain states and experiences (which he doesn’t deny), than he does on his own philosophical conclusions about this hard data. Kastrup doesn’t explicitly state his philosophical position on all that hard data until 29 minutes into a 34 minute video. And that was in response to a question asking for an “alternative” take on the data.

It can easily be argued that all of Kastrup’s words on the neuroscientific data are but a prelude to his philosophical and spiritual gloss on that data. Alternatively, Kastrup’s philosophical and spiritual positions (or beliefs) might well have been the motivation for finding the scientific data to back them up in the first place. Thus, Kastrup’s spiritual philosophy might have been wagging the scientific dog all along.

(In one case Kastrup almost(?) admits as much in an interview with the science writer John Horgan in which he states that he took an immediate and intuitive position against the possibility of — strong? - artificial intelligence and only after that did he begin — what he calls - “refining” that position with actual scientific data.)

Finally, even if all of the neuroscientific data Kastrup relies on is partly — or or even entirely — true, it still doesn’t (automatically) lead to anything that would establish the existence of Cosmic Consciousness or the position of Cosmic Idealism. And that’s simply because Kastrup’s position is philosophical, not scientific. Moreover, using scientific data to back up a philosophical and spiritual position doesn’t thereby render that position scientific. It certainly won’t suddenly become a part of science. Indeed, this is just as true of materialism (as Kastrup himself often tells us) as it is of Kastrup’s Cosmic Idealism.

Now a few words on Kastrup’s video presentation itself, which is the basis on this essay.

Kastrup’s Video Presentation Itself

Kastrup’s video presentation is from a conference which has the surface appearance of being an event which included many different viewpoints. Yet it’s actually hosted by member of the Essentia Foundation (Professor Sarah Durston — who’s on the Academic Advisory Board of the Essentia Foundation), of which Kastrup is the executive director. Added to that fact is that the host doesn’t critically — or otherwise — question Kastrup on anything he says. And even the three speakers (Professor Henk Barendregt, Professor Heleen Slagter and Steve Taylor, PhD) all have strong affinities to Kastrup’s philosophical work.

More relevantly, the following words can be found directly under the YouTube video:

“In his opening presentation of the ‘Science of Consciousness’ conference 2021, Essentia Foundation’s executive director Bernardo Kastrup reviews the neuroscientific evidence and discusses what it actually tells about consciousness. He also discusses, in explicit and specific detail, what he perceives as widespread physicalist confirmation bias in both academia and mainstream media.”

Kastrup’s Response to a Guardian Article

Bernardo Kastrup focuses much on a Guardian article and severely criticises it. (The article: ‘LSD’s impact on the brain revealed in groundbreaking images’ | Science | The Guardian.) Kastrup’s position is summed up by the last words of the passage above:

“[Kastrup] also discusses, in explicit and specific detail, what he perceives as widespread physicalist confirmation bias in both academia and mainstream media.”

As can be seen above and elsewhere, many of Kastrup’s criticisms of other philosophical — and indeed scientific — positions are quite conspiratorial in nature, as well as being highly personalised, somewhat arrogant and rhetorical. (On videos and in interviews, Kastrup comes across as having a almost narcissistic belief in himself and in his own views.)

(Note: Kastrup has a go at the Washington Post, The Conversation and CNN. He uses the words “gratuitously misleading”, “Why don’t they just tell the truth?” and “in your face bias”. He also accuses these newspaper journalists of being “physicalists”. Added to all that are his strong words on Sabine Hossenfelder, Sam Harris and even on the mild-mannered Philip Goff - of whom he says: “I have lost a great deal of intellectual respect for Philip’s positions and arguments. Therefore, I have little motivation to continue the engagement with him.” Kastrup’s comments on Harris and Hossenfelder, however, are far worse than that.)

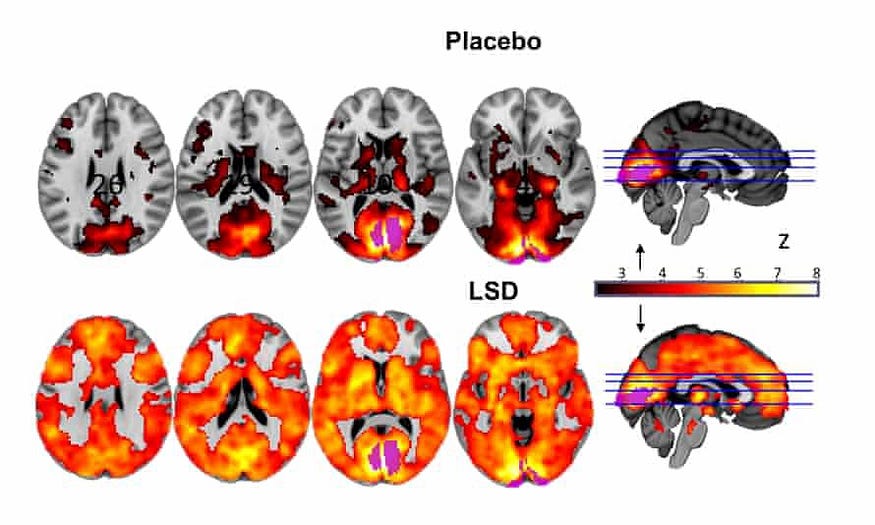

More relevantly to this essay, Kastrup sneers and literally laughs at much — or even all — of the Guardian article he focusses on. He specifically laughs at a Guardian image (see below) in which the journalist supposedly mistakes the parts of the brains which are coloured orange (in the mage) with increased activity, rather than decreased activity. (The image is accompanied with the words “lots of orange”.) This may well be a simple and honest mistake — that’s if it’s a mistake at all. Yet Kastrup gives the image and entire article an embarrassingly conspiratorial interpretation and boils in all down to a commitment to “physicalism”, which he claims is “a failing paradigm”.

The aforementioned image doesn’t matter that much anyway because the scientists quoted in the article — as we shall shortly see — make it very clear that there is much brain activity during psychedelic experiences.

In any case, Kastrup is definitely demanding that newspaper articles be written in the manner and style of academic papers… at least in the cases which he cares about.

Yet Kastrup himself isn’t a neuroscientist.

Indeed (as far as I can see) he’s never formerly studied neuroscience at a university. That said, the Guardian writer Kastrup tackles, Ian Sample, isn’t a neuroscientist either. However, he was a journalist at New Scientist and worked at the Institute of Physics as a journal editor. (He also has a PhD in biomedical materials.) Of course Kastrup has a strong scientific background too. So the fact that both Kastrup and Sample have such backgrounds doesn’t make either of them the last word on any scientific subject. And this is especially the case because, if we read Bernardo Kastrup right, the Guardian’s Ian Sample has got it all wrong when it comes to psychedelic experiences.

Kastrup’s Detail on the Guardian Article

Kastrup is emphasising (what he takes to be) the fact that there is less brain activity during a psychedelic “trip” than in normal states. The thing is that the Guardian article Kastrup laughs can be interpreted as not exactly stating the opposite of this. (That is, that there is more brain activity during a trip.) Instead, it simply highlights the different kinds of brain activity which occur during psychedelic trips.

Thus the central theme here are the distinctions which can be made between increased brain activity, decreased brain activity and what Kastrup calls “activity variability”.

The Guardian’s (or Ian Sample’s) position is summed up in this way:

“A dose of the psychedelic substance — injected rather than dropped — unleashed a wave of changes that altered activity and connectivity across the brain.”

The Guardian concludes with these words:

“This has led scientists to new theories of visual hallucinations and the sense of oneness with the universe some users report.”

So, according to the Guardian, this “oneness with the universe” is actually a result of the “wave of changes that altered activity and connectivity across the brain”. Kastrup, on the other hand, believes that this oneness with the universe — along with much else! — is down to the subjects’ actual (or real) oneness with the universe. That is, Kastrup believes that the minds of the subjects experiencing psychedelic experiences disengage from the physical brain and become one — or at least attempt to become one — with Cosmic Consciousness.

In fact Kastrup may be right (at least in a weak sense) about a “materialist bias” because the neuroscientist and professor Robin Carhart-Harris (as quoted in the Guardian article) states the following words:

“This experience is sometimes framed in a religious or spiritual way, and seems to be associated with improvements in wellbeing after the drug’s effects have subsided.”

To Kastrup, on the other hand, “[t]his experience” isn’t actually about these experiences being “framed in a religious or spiritual way” at all. It’s about this experience actually being religious or spiritual. That is, it’s about psychedelic subjects tapping into Cosmic Consciousness.

(In Kastrup’s general philosophy, this tapping into Cosmic Consciousness comes with a hell of a lot of extra spiritual and indeed political baggage. See, for example, here.)

Moreover, the Guardian spreads yet more of the (what Kastrup calls) “materialist paradigm” here:

“Further images showed that other brain regions that usually form a network became more separated in a change that accompanied users’ feelings of oneness with the world, a loss of personal identity called ‘ego dissolution’.”

More technically, the following is just one more example of brain activity (again, as cited by the Guardian) which occurs during a psychedelic trip:

“The brain scans revealed that trippers experienced images through information drawn from many parts of their brains, and not just the visual cortex at the back of the head that normally processes visual information. Under the drug, regions once segregated spoke to one another.”

Added to all that, Robin Carhart-Harris is quoted again stating the following:

“We saw many more areas of the brain than normal were contributing to visual processing under LSD, even though volunteers’ eyes were closed.”

So are all the words above (both from the Guardian and the neuroscientists cited in other newspaper articles) simply yet more examples of the (as the Essential Foundation puts Kastrup’s position)

“widespread physicalist confirmation bias in both academia and mainstream media”?

Ironically, both the Guardian and Kastrup may well be working from the same hard data… Or at least that is something that Kastrup would like to stress. And he does so, for example, when he judgmentally and sternly claims that the Guardian (or Ian Sample) has simply misinterpreted that data!

In any case, it’s unequivocal that, at least according to the Guardian and the scientists it quotes, there is much brain activity during psychedelic experiences!

Case Studies and Details

Bernardo Kastrup argues (or merely hints at in this particular video) that a decrease in brain activity in the brain (during a session of hallucinogenic drugs) means that the brain isn’t involved at all when it comes to such hallucinogenic experiences. (It will be explained why this extreme expression of Kastrup’s position is implicit in what he says.)

Yet a reduction in some areas of brain activity (during psychedelic experiences) doesn’t mean a reduction in all areas of brain activity. It certainly doesn’t mean that the brain isn’t involved in any way in such experiences.

What these (what Kastrup calls) “deactivations” of brain activity may simply mean, for example, is that the psychedelic subjects’ cognitive processes are less prevalent during their psychedelic experiences. Thus, the subjects allow themselves to be (as it’s sometimes put) “immersed” in their experiences. (This is how the advocates and takers of hallucinogenic substances themselves often put it.) Hence the lack of activity in certain parts of the brain.

At one point in the video Kastrup explicitly states that “not a single part of the brain becomes more [my italics] active” during a psychedelic trip. That may well be true. Yet the brain is still active at such a time. And there’s certainly no demonstration of any independence of psychedelic experiences from the brain.

Kastrup also compares what happens during a psychedelic trip to “the brain going to sleep”. Yet, as far as can be seen, no neuroscientist has claimed that dreams — or simply sleep — are independent of the brain or ever concluded such a thing. And neither do they claim that there is zero brain activity during sleep. (As earlier, this is a reference to zero activity when it comes to dreams and other states of sleep; not to the general functioning of the brain when subjects are asleep.)

Kastrup knows that that there is much brain activity even during deep sleep because he actually mentions it. ( See the scientific detail here. ) The words “much” was just used. So it can be conceded that even though there is much brain activity during sleep, there may still be less brain activity than when awake. And this may indeed parallel what happens during psychedelic experiences. That is, there is much brain activity during psychedelic experiences, but still less than there is during non-psychedelic states.

This means that Kastrup bringing up sleep doesn’t seem to do the job he wants it to do.

So what does all of the data show Kastrup?

It doesn’t show that experience or consciousness has any kind of independence from the brain or from brain activity. It simply shows that different things occur in the brain during hallucinogenic experiences than which occur at other times. And that fact has the air of the obvious about it.

This means that Kastrup’s “black swans” (his term for the cases which he believes show us that not all experiences are “correlated” with activity in the brain) are not black swans at all. They’re simply different types of white swan — that is, different things occur in the brain when under a hallucinogenic substance than which occur when not under such a substance.

So how does Kastrup draw his very broad philosophical conclusions from his supposed black swans?

All this is pretty obvious: (1) Different experiences will involve different parts of the brain and different levels of activity in the brain. (2) Some parts of the brain will be less active and other parts will be more active during different experiences. (3) It may indeed be the case that, overall, the brain is less active during a psychedelic trip.

Kastrup also focuses on the “rich experiences” which are had during psychedelic trips. In Kastrup’s own words:

“Psychedelic substances have been known to induce highly complex, intense, non-local, transpersonal experiences.”

To Kastrup, this demonstrates that there is something very weird or spooky about rich experiences running alongside decreased brain activity.

Yet Kastrup fails to say (or realise) what a psychedelic “rich experience” actually is. He conflates what the subject makes of his experiences under the influence of a hallucinogenic substance and the experiences themselves. Of course, those who take such substances make a lot of their experiences under their influence. (This is well documented.) But that doesn’t mean that the experiences actually are “richer” in anything other than a vague (or purely personal/psychological) sense. And it certainly doesn’t mean that the experiences are (as Kastrup puts it) “non-local” just because certain (i.e., not all) subjects take them to be non-local.

(Not that any of the psychedelic subjects would have used the highly-technical term “non-local” — unless, that is, they already had an interest in these areas of philosophy and science. See quantum non-locality.).

Conclusion

To repeat.

In order to establish his radical position, doesn’t Kastrup need to demonstrate that there is zero brain activity during psychedelic experiences? Note that this isn’t a demand that Kastrup should demonstrate zero brain activity simpliciter. It simply means that he should demonstrate zero brain activity in relation to the psychedelic experiences themselves..

More technically, what Kastrup calls “deactivation” doesn’t mean that there’s zero brain activity during psychedelic trips. Yet that’s precisely what Kastrup would need to establish both his scientific position and his philosophical conclusions (or speculations). Indeed, Kastrup even admits that brain “activity does remain” during psychedelic experiences (i.e., as that activity relates to those experiences). Kastrup also uses the words “reduced activity”, “less active”, “residual activity” and “activity variability” in reference to what occurs during psychedelic experiences. In other words, Kastrup’s “activity variability” (which Kastrup pits against what he believe are the many false claims about increased brain activity) obviously doesn’t equal zero brain activity.

In a strong sense, then, if Kastrup isn’t making these very radical claims about zero brain activity (which may be hidden beneath his very-academic and technical prose), then he simply can’t establish his radical philosophical position of Cosmic Idealism. Moreover, if he isn’t claiming that there’s zero brain activity during psychedelic experiences, then what, exactly, is he claiming?

In other words, simply arguing that the brain is slightly less active (or whichever technical wording Kastrup prefers to use) during psychedelic experiences clearly doesn’t establish Kastrup’s central philosophical thesis — i.e., that psychedelic trippers are tapping into Cosmic Consciousness and thereby freeing themselves from the biological and physical brain.

*) See my essay, ‘The Idealist Philosopher Bernardo Kastrup vs. Materialism’.

No comments:

Post a Comment