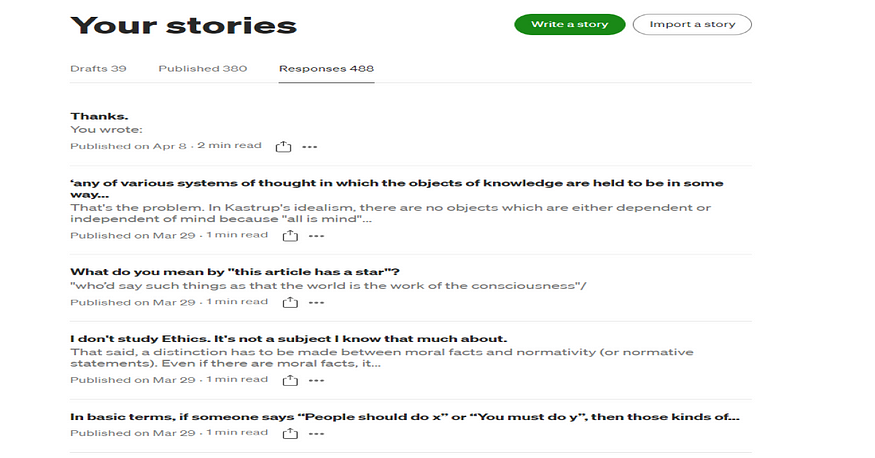

Selected (mainly critical) responses to my essays on Medium - and my replies to them. (1)

Quantum Weirdness

Mirco Milletarì Ph.D.’s response:

“Your main point is that quantum particles are neither particles or waves, but a ‘bit of both’, that is indeed the standard point of view.”

My reply:

“It isn’t really my own point of view — I’m not a physicist. I was putting (as you put it) ‘the standard view’. After all, (as it were) fusing two modes of classical description (i.e., waves and particles) won’t really be any better that using a single mode of classical description (i.e., a wave or a particle).”

Mirco Milletari continued:

“A quantum object is really neither of them (this is what I was taught in QM 01) but some of their properties can be described within one of the two frameworks. The quantum object is something else, it is not weird as much as a wave is not weird for not behaving like a particle.”

My reply:

“I believe that’s largely we’re I’m coming from. To be finicky, even the word ‘object’ is problematic because classical objects are seen to be what philosophers call individuals (which has nothing to do with how that word is used in everyday life, politics, sociology, psychology, etc.). You can conceive of a classical individual/object existing in many different environments and still being that self-same object. Yet you can’t really do the same when it comes to most quantum xs. In other words, quantum xs are parts of systems, fields and/or states and have no real identity separate from them. That said, some philosophers and theorists argue the same about classical objects/individuals too!”

More Quantum Weirdness

Frank Front’s response:

“But Micro, quantum effects are very weird from a lay reference frame life experience based intuition…. those who understand the why and to some extent the how — in this case those with some pretty deep exposure to quantum physics theory. And that is not most people. So for most people, yeah this stuff is weird. Very weird.”

My reply:

“I can see your point. However, it’s often physicists themselves — and, of course, popular science writers — who stress the ‘weirdness’ of quantum mechanics, not laypersons. (I suspect that many of them do so to entice laypersons in to physics because they’re so desperate to create an interest in the subject.) So some of those who understand the theory also thought that things are weird — Richard Feynman is a good example. Yet since Feynman completely dismissed any philosophical — or any — account of the quantum formalism, then he had no right to say that. Feynman strongly believed in the “shut up and calculate” mantra. So why did he also say that QM is ‘weird’? The calculations and mathematical formalisms aren’t at all weird. Only the (rival and/or conflicting) interpretations are weird. And Feynman largely rejected such things.”

*************************************

Roger Penrose on Gödelian Truth

Chuan Hiang Teng’s response:

“This is profound. I would add that in order to ‘see’ mathematical truth, one must have the ability ‘invent’, reconfigure, reason from the material to an abstract state with a superstate posited in the mind. If we train our minds to think objectively and with agility and flexibility being able to combine different knowledge and theories, our neurons in the physical sense will follow suit in its reconfiguration accordingly. The spiritual self must drive the physical self. In this sense, computers will never have this ability sense I cannot envisage how human beings can create consciousness. It is far more superior.”

My reply:

“The problem is that, as far as I can see, Roger Penrose is mainly — or even exclusively — talking about Gödel sentences (or truths) here. And the problem is that not many people can ‘see’ them — not even some mathematicians. In addition, some reject Gödelian ‘truth’ entirely. (The word ‘truth’ isn’t apt when it comes to mathematical systems.) What’s more, if seeing Gödelian truth is fundamental for mathematical truth and indeed consciousness itself, then where does that leave 99.9% of the population? Unless Penrose simply means that human subjects merely have the potential to see Gödelian truths.”

******************************

Does the Brain “Produce” Consciousness?

Lawrence Bloom’s response:

“The brain produces consciousness and thoughts like the urinary system produces urine.”

My reply:

“That’s also the philosopher John Searle’s position. As you can see in the essay, Daniel Dennett ridicules it. One can observe someone’s urinary system and someone’s urine. Yet you can’t observe someone else’s consciousness or the relation between the the brain and consciousness. You can also observe a person’s behaviour — both bodily and vocal. And some philosophers take that to be — at least partly — constitutive of consciousness. But many other philosophers don’t.“The urinary system is well understood, both from an evolutionary and a physiological perspective. That can’t really be said about consciousness… Or can it? Also, surely you can’t have a urinary system without urine. Though many philosophers have argued that you can have a brain without consciousness… or at least without consciousness as it’s understood by those who defend qualia, etc… As it is, I sorta see myself as a physicalist. That said, I have serious problems with your position.”

More on the Brain Producing Consciousness

Johnny wrote:

“We could go so far as to say that, ‘all facts are physical processes,’ rather than ‘all facts are causally dependent upon physical processes’…”

My reply:

“I don’t accept that. Then again, the word ‘fact’ is interpreted in many ways. Many definitions amount to mere stipulations. (Perhaps all are!) Some see facts as ‘ways of dividing up the world’. Or as ‘the content of true statements’… Or as… I’ve never seen all — or any — facts as actually being physical processes. Some facts are about — or refer to — physical process. But facts surely can’t be physical processes themselves. I can hardly make sense of that.”

Johnny’s response:

“If we understand ‘awareness’ to be awareness of physical change…”

My reply:

“I’m not sure that awareness needs to be of ‘physical change’. Though that may be useful for a philosophical project. Can’t someone be ‘aware’ of an abstract mathematical equation and its solution? Can’t someone be aware of a blank white wall on which nothing happens? Etc."

Johnny’s response:

“and if we understand that ‘process’ need not be defined in terms of ‘this causing that’ but rather as ‘this has become that,’ then we could say that ‘to be aware’ is to be aware of the continual ‘becoming’ of our physical world.”

My reply:

“Yes; but can’t ‘this has become that’ mean that this causes that? That is, if x becomes y, then that can be because x causes y. Then again, can x become something it isn’t? I suppose so. Thus, in that case, if x becomes y, then x ceases to exist when y comes on the scene. But that wouldn’t work in the brain-to-consciousness case because the brain states and events necessary for consciousness don’t cease to exist when we become conscious of something. So, in this case, it can’t be a case of brain states (or brain events) becoming something else. This can work in other cases. A lava becomes a butterfly. Yet, arguably, there is still a temporal and causal (which you reject) identity over time. Again, that doesn’t work for the brain’s relation to consciousness.

“Your replies are interesting; though I don’t think I agree with them.”

*****************************

Define Your Terms

Alex Shkotin’s response:

“Any definition is an element of a theory (theoretical knowledge). Taken alone it’s useless. What is a theory? What kind of theories do we have? What is a system of definitions of this or that theory? Axioms are a kind of definition. And the main question: theory of what?”

My reply:

“I’m not expecting anything deep, heavy or technical when I ask for a definition in a debate or discussion. I just want to know what someone means by the terms he or she is using. If I don’t know what a person means (or can’t even guess what it means(, then the exchange becomes literally pointless — at least to me.“Also, you can’t overplay the ‘theory’ behind all the terms people use. If you did, then I wouldn’t understand your response either. I’d need to know the theory behind the terms you’ve used and the theory behind your entire response. As it is, I know what you’re saying. So, in this case at least, the background theory isn’t required.”

***********************

Michael Williams Doesn’t Reject Truth and Knowledge

Paul Fiery’s response:

“My plain point is this: When Michael Williams makes a statement such as ‘There are no such things as knowledge and truth,’ that’s it. This is the end of the line. His further utterances can be disregarded, for he has declared them empty.”

My reply:

“That’s why you should read the articles you respond to. Firstly, Michael Williams doesn’t say exactly that. I do. If you note the title (‘Michael Williams: There are No Such Things as Knowledge and Truth’), the words after his name aren’t in quotation marks. If they were his precise words, then I’d have put them in quotes. Not only that, the article begins this way:

‘Despite the provocative title of this piece, the British philosopher Michael Williams (1947-) does accept that “[w]e can have an account of the use and utility of [the word] ‘know’ without supposing that there is such a thing as human knowledge’”.

“And, moments later, there are the following words:

“Williams (again) happily concedes that ‘[a] deflationary account of ‘know’ may show how the word is embedded in a teachable and useful linguistic practice’.’

“So you should have taken on board two aspects of the title itself. 1) The words aren’t in quotation marks. 2) There are No Such Things as Knowledge and Truth. The article is explicit and repetitive on that subject — Michael Williams has a problem with seeing knowledge and truth as things. That is, as entities which are also natural kinds or even platonic universals. This seems to show that you either didn’t read the article or you simply didn’t understand it.“Do you really believe that Michael Williams — or anyone else knowledgeable about philosophy — wouldn’t be aware of your possible self-referential trap? It isn’t, however, a self-referential trap because Williams believes that we can use and accept the word ‘know’ and even teach it. In other words, we can defend our claims without also believing that knowledge and truth are fixed and determinate things — abstract or otherwise. But, sure, perhaps Williams qualifications and take on ‘practices’, ‘use’, etc. doesn’t work. But at least take on board what his actual position is...“So, all in all, it seems that you only responded to the title alone and that explains why you haven’t mentioned any detail from the actual essay. (This time you even misread the title precisely because you didn’t read the essay itself.) This time you kind of admit that because of the title, you didn’t read the article — not even out of curiosity. But this may be what you do with all other articles too — respond to titles and perhaps a few other words glanced at during speed-reading….. The rest of your response is about other subjects too. You even say I should have something to say on ‘nonsense’ — which I have! But this essay isn’t about nonsense or what is taught in universities. Ironically, these subjects were vaguely touched upon in my last essay!”

[I can be found on Twitter here.]

No comments:

Post a Comment