Does naturalistic dualism lead to panpsychism?

Introduction: What Hard Problem of Consciousness?

It’s worth stating — at the onset — what the Australian philosopher David Chalmers (1966-) hopes to achieve by advancing (his) naturalistic dualism.

Chalmers believes that panpsychism (or, more specifically, panprotopsychism) could be a solution to the “hard problem of consciousness”. (Chalmers himself coined that phrase.) That is, if everything (including the brain and all its parts) has — or instantiates — phenomenal properties, then perhaps there’s no (deep) problem with the link between the brain and the phenomenal. That’s primarily because every physical thing is — or instantiates — the phenomenal from the very start.

This also means that in panpsychism there may be no (strong) emergence either. That is, surely the phenomenal can’t emerge from what is already (at least party) phenomenal. Indeed the phenomenal can’t be reduced to the phenomenal either — for the same reason. And, finally, the phenomenal can’t supervene on the phenomenal. (All that said, see the short discussion of the Combination Problem in the last section of this essay.)

Property Dualism is Dualism

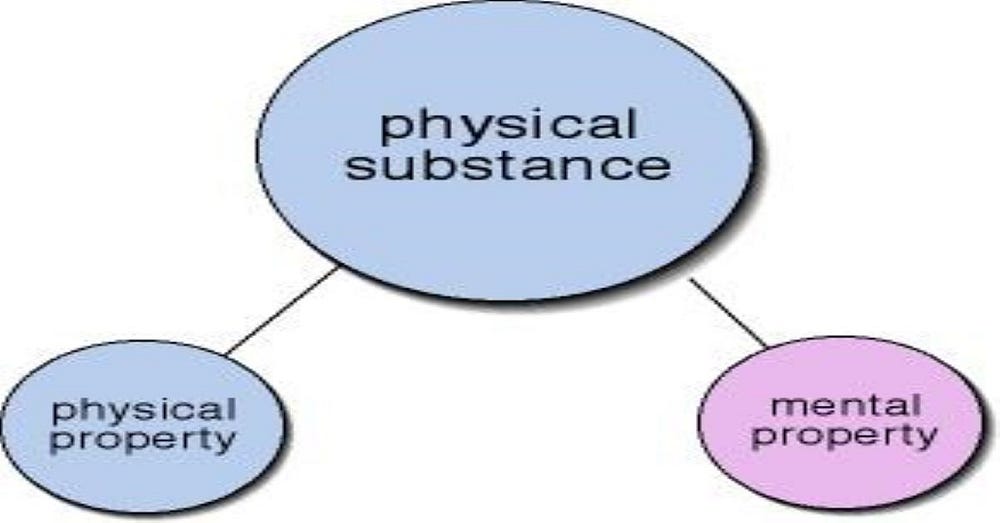

David Chalmers’ philosophical position is one of property dualism.

This position has it that the world is composed of just one kind of substance. However, that (physical?) substance has two distinct kinds of property: physical properties and phenomenal (or mental) properties.

Yet there often seems to be various kinds of complication (or plain conflation) on this subject. What’s meant by that statement is that some property dualists argue (or simply imply) that firstly we have (a) substance, and only then do we have the two kinds of property of that substance. Other property dualists, on the other hand, argue that it’s the physical itself (i.e., without any talk of substance) which has two kinds of property.

This means that we’d need to know what substance is regardless of its “properties”. That said, substance is a philosophical term of art which tends to take us very far from anything known or accepted in physics or in any other science.

[It’s true that historically the term “substance” has been used in science — or at least in premodern science. Indeed the term is still used in chemistry. However, chemical substances bear little resemblance to the various and many substances of philosophy.]

More relevantly to this essay, we now need to know how two distinct kinds of property can exist (or can be instantiated) together in the same substance (or in the same x) and why they are so.

So is this joint existence (i.e., of two very-different properties) in the same substance (or x) any less problematic than the joint existence of “body and mind” (i.e., two other completely different substances) in substance dualism or, perhaps less accurately, in Cartesian dualism?

In addition, this position basically boils down to the very philosophical (or ontological) division of a given x into its having two other kinds of property: the intrinsic and the extrinsic. In this case, the intrinsic is taken to be phenomenal and the extrinsic is taken to be physical.

All this means that we have a singular (or even monistic) x which is (to use Wittgenstein’s phrase) “the substance of the world”. Yet that x still has two very different kinds of property.

This position, therefore, gives up on substance dualism in order to embrace a dualism of properties.

In substance dualism, the mind and body are (rhetorically) ripped apart. In property (or, as we shall see, panpsychist) dualism, on the other hand, we have a given x which just happens to have two very different types of property.

But why is property dualism any better than substance dualism?

It is different, sure; but why is it better or less problematic?

What’s more, why on earth should we buy this neat, tidy and — perhaps also — artificial philosophical (as it were) binarism of a given x and its having both physical and phenomenal properties? And, in parallel to that, why should we also buy the equally neat and tidy intrinsic-extrinsic binarism to which that former binarism is very tightly (or even essentially) linked?

It must now be said that David Chalmers himself sees his own position as dualist.

[See David Chalmers’ video presentation ‘What is Property Dualism?’. This puts the case for — or at least explains — property dualism. This position is also very much like the more strictly ontological dual-aspect theory.]

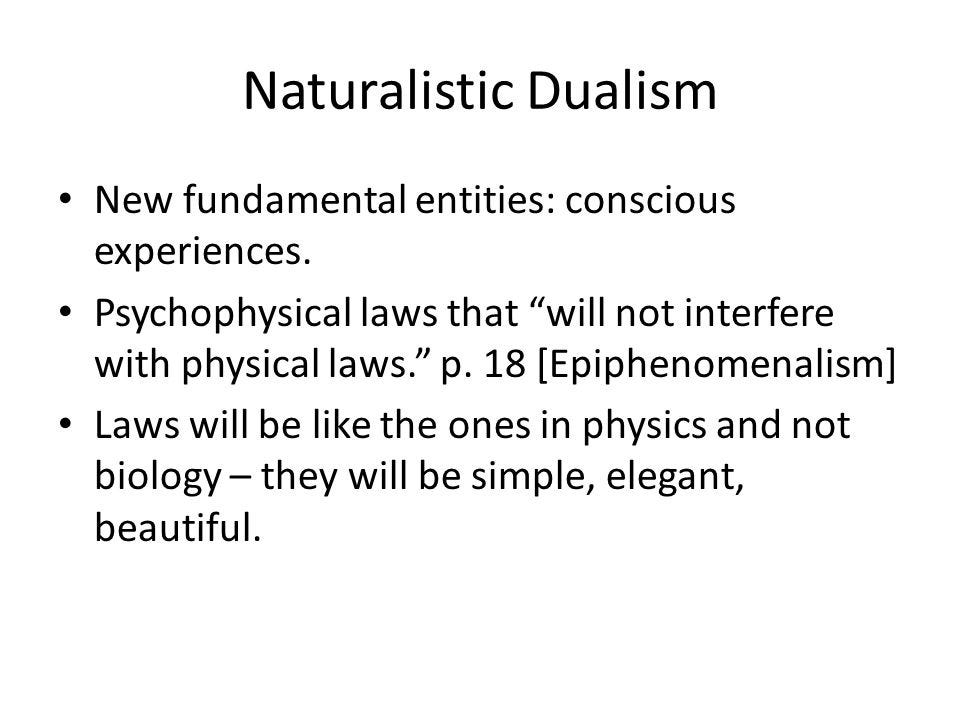

Naturalistic Dualism

Why does Chalmers see his own position as being a type of dualism?

Take Chalmers’ own words on this. He writes:

“[T]he fact that consciousness accompanies a given physical process is a further fact, not explainable simply by telling the story about the physical facts.”

The problem with saying (as Chalmers does elsewhere) that naturalistic dualism is “compatible with all the results of contemporary science” is that this is exactly what idealists (from Bishop Berkeley to Donald Hoffman and Bernardo Kastrup) have also argued about their own (in the plural) idealisms. What’s more, panpsychists have argued the same about panpsychism. Indeed theists and many others — and even some of those who make specific religious claims (which are clearly not naturalistic) — have argued that their own positions/claims don’t (to use another phrase) “contradict science”.

Moreover, religious or spiritual people can argue that their views are examples in which (to use Chalmers’ words) “our picture of nature has [simply been] expanded” — i.e., not contradicted. (Deepak Chopra makes these kinds of claim all the time — see here.)

So perhaps the situation with all the philosophical and religious isms above jointly (as it were) owning the same (to use Chalmers’ words) “results of contemporary science” is a very direct consequence of the fact that theory is underdetermined by the data or evidence.

Now let’s move on and provide a little detail on Chalmers’ phenomenal properties and intrinsic properties.

Phenomenal Properties are Intrinsic Properties

In David Chalmers’ philosophical scheme, there’s a very tight (or even necessary) link set up between phenomenal properties and intrinsic properties. That is, Chalmers deems phenomenal properties to be intrinsic properties.

Chalmers accepts what he also calls “the physical”. (He’s not an idealist.) However, he believes that the physical has phenomenal properties. In his own words:

“If one allows that intrinsic properties exist, a natural speculation given the above is that the intrinsic properties of the physical — the properties that causation ultimately relates — are themselves phenomenal properties.”

It’s clear that Chalmers is being speculative about intrinsic properties here, not speculative about phenomenal properties. This seems to be an acceptance — or even assumption — on Chalmers’ part that such properties exist… and only then do we need to speculate about their nature.

So here we need to note the importance of the intrinsic-extrinsic binary in Chalmers’ philosophy.

The physical obviously isn’t being factored out of Chalmers’ philosophy (i.e., as it would be if he were an idealist). And neither is the phenomenal (or consciousness/experience). Instead, we have one thing (i.e., the physical — Chalmers doesn’t use the term “substance”) with two kinds of property: the physical and the phenomenal.

Of course that grammatical formulation doesn’t work in that it can hardly be said that the physical is a property of the physical. On the other hand, it’s fine to say — at least grammatically - that the phenomenal is a property of the physical.

So instead of saying that both the physical and the phenomenal are properties of the physical, we can say that the physical and the phenomenal are properties of x — where x is a symbol for some kind of noumenon, substance or simply something before it’s described or accounted for in ontological (or in any) terms.

Does the physical have any other properties other than the phenomenal? Yes; but none of them is intrinsic.

This means that Chalmers is arguing that the physical property of x is extrinsic; whereas the phenomenal property (of the very same) x is intrinsic.

Now just as property dualism can be tied to panpsychism, so it can also be tied to (or be an example of) non-reductive physicalism.

Non-Reductive Physicalism

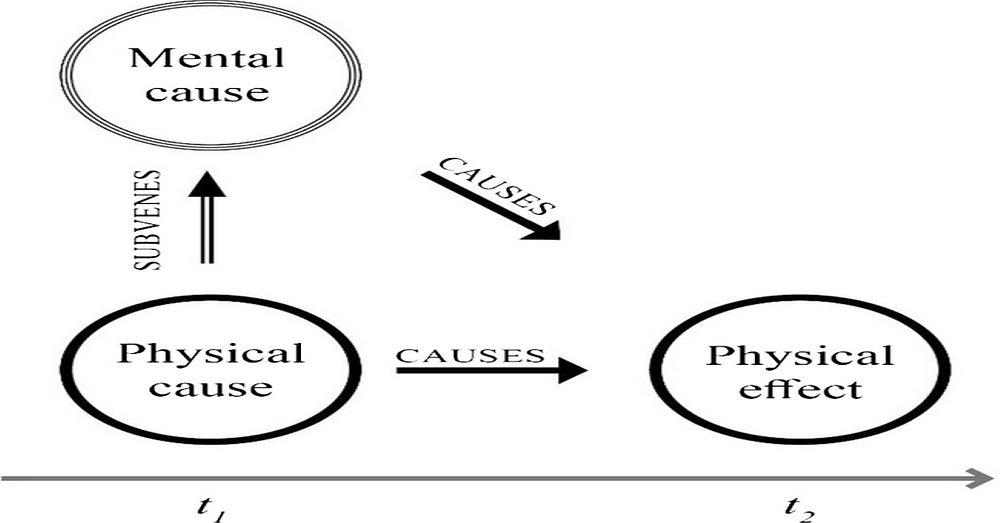

Non-reductive physicalism has it that “the mental” (or a phenomenal property, in Chalmers’ case) isn’t ontologically reducible to the physical (or to the brain).

Yet non-reductive physicalism also has it that mental states (or phenomenal properties) are physical in that they’re caused by physical states. However, on this non-reductive picture that doesn’t mean that mental states (or phenomenal properties) are also ontologically reducible to such physical states.

Yet if mental states (or phenomenal properties) literally are physical states, then why aren’t they ontologically reducible to physical states?

That said, if any given x (literally) is y, then surely that x can’t also be reduced to y. That’s because x is y. So x can’t be reduced to x.

[Loosely, one “mode of presentation” or “sense” of a given x can be reduced to another mode of presentation of that very same x. This issue can’t be tackled here.]

Now let’s concentrate on Chalmers’ phenomenal properties — rather than the “mental states” usually referred to in this debate.

To repeat. If phenomenal properties are physical states, then phenomenal properties can’t be reduced to physical states because phenomenal properties are physical states.

There is a similar problem here.

As already stated, in the non-reductive picture it’s argued that mental states are physical in that they are caused by physical states. However, mental states aren’t ontologically reducible to such physical states. Yet here again if Chalmers’ phenomenal properties literally are physical, then how can they also be caused by physical states? Does this mean that such physical states are causing themselves? Alternatively, is this a case of one set of physical states causing another set of physical states?

To repeat. On the non-reductive physicalism picture, we have a seeming contradiction. Firstly, we have this position:

mental states (or phenomenal properties) are physical

Yet we have the following position too:

a mental state (or phenomenal property) isn’t the same thing as some physical state

This means that although a mental state (or phenomenal property) is physical, it’s not the same thing as a physical state. Yet how can it be physical if it’s not the same thing as something physical? Unless, as just stated, we have the mental state (or phenomenal property) which is physical, and then we have another physical state which is something else. In that case, why is the mental state (or phenomenal property) physical at all?…

… Of course the panpsychist and/or property dualist (if not all non-reductive physicalists) attempts to get around this by arguing that the physical has two “aspects” — the physical and the phenomenal.

Thus a phenomenal property is only one aspect of something physical. And, because it’s only one aspect of a given physical x, then it can’t also be identical to that physical x. That is, something which is more-than-x can’t be entirely identical — or reduced — to that x. That’s mainly because that more-than remainder (whatever it is) will be left out of the identity or the reduction.

Now David Chalmers’ position is somewhat complicated by his introduction of a term which is (in his case at least) essentially borrowed from contemporary physics: information. (This isn’t, of course, to say that the word hasn’t been used in many other contexts.)

Information is Physical

Panpsychism offers us a necessary and vital link between the physical and the phenomenal. Chalmers writes:

“This informational view allows us to understand how experience might have a subtle kind of causal relevance in virtue of its status as the intrinsic aspect of the physical.”

Here Chalmers talks about an “intrinsic aspect of the physical”, rather than the earlier phenomenal aspect (or property) of the physical. And this is Chalmers doing so again in the following passage:

“[A] natural hypothesis: that information (or at least some information) has two basic aspects, a physical aspect and a phenomenal aspect.”

And elsewhere he writes:

“We might say that phenomenal properties are the internal aspect of information.”

Put simply, then, Chalmers links the phenomenal to the informational.

So instead of talking about any given x (or the physical) having “two basic aspects”, it’s now being argued that it’s “information” which does so.

Importantly, the two passages above must now be related to Chalmers’ earlier highly-relevant comment that “[w]here there is [] information processing, there is [] experience”.

Thus we now need to tie information to the physical (or the physical to information).

Chalmers fully accepts that information needs to be implemented — that is, to be physically (to use a term analytic philosophers seem to prefer) “realised”. And because information is physically realised, then we now also have “properties that causation [can] ultimately relate[]”.

Again, Chalmers concedes that such information is — or even must be — “embodied in physical processing”. That is, information is physically implemented, embodied or realised. (In this case, in the human brain.) In this picture, then, information never runs free of the physical.

[Many — perhaps almost most — theorists in artificial intelligence believe that the right algorithms can bring about not only intelligence and mind, but also consciousness. See my ‘Roger Penrose on Algorithms and Consciousness’.]

Thus, if information processing is physically realised, embodied or implemented, and the physical also instantiates phenomenal properties, then we “could answer a concern about the causal relevance of experience”. On the other hand, if the phenomenal has no strong tie to the physical (as well as “the physical domain [being] causally closed”), then what role can the phenomenal play if it’s merely “supplementary to the physical”?

To recap. Chalmers firstly tied the phenomenal to the physical, and then he tied the phenomenal to the informational. Added to that is the idea that information itself is tied to the physical.

Now take the notion (or reality) of emergence.

Chalmers’ Broader Take on the Phenomenal-Informational Link

All the above helps us tackle the issue of emergence.

Arguably, in panpsychism emergence is no longer (as) problematic as it is for many other philosophical theories.

Chalmers himself continues with some grander conclusions in the following passage:

“This [informational view] has the status of a basic principle that might underlie and explain the emergence of experience from the physical. Experience arises by virtue of its status as one aspect of information, when the other aspect is found embodied in physical processing.”

It’s certainly true that if we have the problem of “the emergence of experience from the physical”, then that experience (or phenomenal property) actually being an “aspect” of the physical — i.e., in the first place — is certainly neat and tidy. In what sense, then, can it even be said that experience emerges at all if it’s already an aspect of the physical?

To repeat. In panpsychism (at least at first glance) there doesn’t seem to be any emergence…

… Except when it it comes to what’s called the Combination Problem. In that case, panpsychists argue (if sometimes implicitly and without always using the word “emergence”) that there can be different kinds of phenomenal properties or entities which emerge from prior phenomenal properties or entities…

… But that’s a big issue which can’t be tackled here.

No comments:

Post a Comment