Keith Campbell stated that “continuity shows that men and one-celled organisms have the same basic nature”.

The Australian philosopher Keith Campbell (who was born in 1938) is one of the founders of what came to be called Australian materialism. He was a professor in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Sydney.

This essay is primarily based on Campbell’s chapter ‘Dualisms’, from his 1970 (second edition, 1985) book, Body and Mind.

This chapter has been chosen because it’s a (relatively) early reference to panpsychism by an analytic philosopher. That is, it occurred some time before the recent interest in — or fashion for — panpsychism.

This new interest in panpsychism can be said to have begun around in 1996, with David Chalmers’ book The Conscious Mind. That said, “analytic panpsychism” partly gained inspiration from Thomas Nagel’s 1979 chapter ‘Panpsychism’ (in his book Mortal Questions). This interest in panpsychism didn’t fully kick in until around 2006, with Galen Strawson’s paper ‘Realistic Monism: Why Physicalism Entails Panpsychism’.

It must now be said that although the word “fashion” was used a few moments ago, it can of course be argued that being against panpsychism was also fashionable for a long period of time (at least within analytic philosophy).

When Did Consciousness Arise?

Even though Keith Campbell didn’t begin with the word “panpsychism”, the following passage expresses the broad gist of what has been called the Panpsychist Argument For Continuity. Campbell wrote:

“If minds are spirits they must have arrived as quite novel objects in the universe, some time between then and now [man and his remote descendants]. But when? We see only a smooth development in the fossil record. Any choice of time as the moment at which spirit first emerged seems hopelessly arbitrary. ”

This seems like an argument that a panpsychist would be happy with.

Of course it’s usually stated that consciousness didn’t just “arrive[]”. It arrived as a gradual process — a result of evolutionary processes and the increased complexity of brains and central nervous systems (among many other things).

In a sense, then, this evolutionary view also parallels the panpsychist argument that not all levels of consciousness are the same. That is, a simple “system” needn’t have the same level of consciousness as a complex system. Nonetheless, that simple system still instantiates consciousness (or, as it’s called by some panpsychists, “proto-consciousness”).

Yet, unlike evolutionists, it’s not only biological systems that panpsychists have in mind: it’s any or every system. Thus if a rock — or even a particle — has (proto)consciousness, then the evolutionary argument (about increasing biological complexity, genetic mutations, environments, etc.) simply doesn’t apply.

In any case, Campbell then applies the same argument not to homo sapiens (or to “man”) as whole, but to an individual human person. He wrote:

“The initial fertilised cell shows no more mentality than an amoeba. By a smooth process of division and specialization the embryo grows into an infant. The infant has a mind, but at what point in its development are we to locate the acquisition of a spirit? As before, any choice is dauntingly arbitrary.”

[It must also be assumed that Campbell’s word “spirit” isn’t really meant in the strictly religious sense. His word “spirit”, therefore, must simply a synonym or cognate for “mind” or “consciousness”.]

The panpsychist will — or must — argue that the “initial fertilised cell” — as well as “an amoeba”! — does indeed instantiate at least a rudimentary level of consciousness. Sure, that fertilised cell (or amoeba) won’t instantiate self-consciousness, cognition or any other higher levels of consciousness (whatever we take them to be). More importantly, it will not think. (Hence the common anti-panpsychism position in which it’s stated that panpsychists believe that, for example, electrons think — see here and here.) In that case, then, there simply is no single “point” at which there’s an “acquisition of a spirit”. Thus, there is no “dauntingly arbitrary” choice we (or at least the panpsychist) need to make either.

Campbell then concluded by putting the somewhat obvious panpsychist conclusion (though without using the word “panpsychism”) to all the above. He wrote:

“Continuity shows that men and one-celled organisms have the same basic nature [].”

Of course we need to know what exactly this “basic nature” is. That is, Campbell merely saying that “all matter shares with man his more-than-material nature” doesn’t tell us much. And it can also be supposed that because this more-than-material is deemed by most (or even all) panpsychists to be basic and fundamental (as well as “intrinsic”), then that’s not a surprise.

Thus because most (or all) panpsychists deem consciousness (or experience) to be fundamental, then, in a strong sense, they don’t need to explain or describe what it is. After all, any description or explanation would be an admission that consciousness isn’t fundamental after all. (To quote the idealist Bernardo Kastrup: “Mind is an irreducible aspect of nature which itself cannot be explained in terms of anything else.”)

So both panpsychists and evolutionists believe in continuity.

So who doesn’t believe in such a thing?

What about dualists?

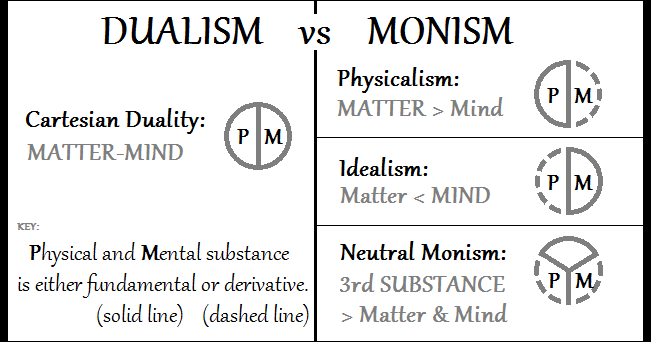

Dualism

Campbell spots the “scientific difficulty for any form of dualism”. It’s that “the continuity of nature leads a dualist inexorably on to panpsychism”.

To dualists, the “soul” (or perhaps Campbell’s “spirit”) isn’t a result of complexity (as with some forms of materialism and evolutionary theory). And, as already stated, dualists also reject continuity (which panpsychists and evolutionists stress).

Thus Campbell picked up on the fact that panpsychists find dualism just as problematic as they find materialism when he wrote the following:

“The scientific difficulty for any form of dualism is therefore this; the continuity of nature leads inexorably on to panpsychism [].”

So one thing we can’t class panpsychists — as well as idealists — as is dualists.

In any case, René Descartes (1596–1660) himself certainly rejected any continuity from animals to human persons. (This isn’t that surprising in Descartes’ pre-Darwinian age.) That said, it can be argued that not all dualists need to be Cartesian dualists. (David Chalmers classes himself as a “naturalist dualist”; and, to take just one more example, see E. J. Lowe’s paper ‘Non-Cartesian Substance Dualism’.)

Again, panpsychists have no problem with such continuity. That is, if stones — and even particles and spacetime — are deemed to instantiate consciousness in the panpsychist picture, then (as it were) allowing mice and birds — and most most certainly cats and dogs — consciousness is no problem at all.

Campbell Against Panpsychism?

Keith Campbell does put a position against panpsychism when he mentions the lack of “direct evidence of mentality” in, say, particles or even cells. Of course there’s no “direct evidence” that non-human animals are conscious either. Indeed, so the arguments go, there is no direct evidence that our fellow human beings instantiate consciousness! (Hence the possibility of zombies, the “problem of other minds”, behaviourism, etc.)

Campbell also argued that panpsychism

“is a speculation which extends the field of the mental far beyond anything warranted”.

That’s okay. Not many (or at least not all) panpsychists would deny panpsychism’s speculative nature.

No comments:

Post a Comment