Hilary Putnam claimed that analytic philosophers “still suffer from the idea that formalising a sentence tells you what it ‘really’ says”; and that “philosophy stands almost entirely apart [] giving much too much significance to an ideal language”. What’s more: “Wittgenstein and J.L. Austin would argue that sentences do not normally have context-independent truth conditions.”

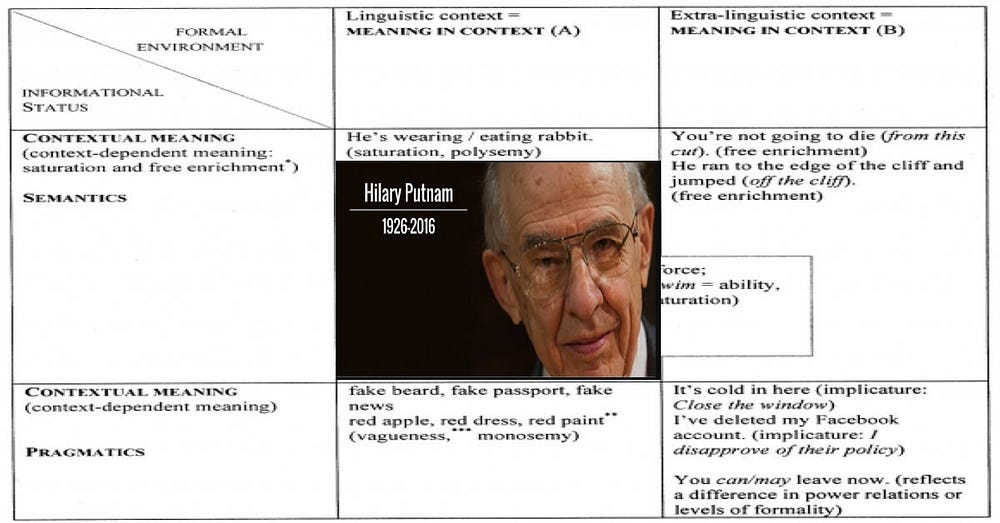

The American philosopher Hilary Putnam (1926–2016) once discussed the various (analytic) philosophers who’d defended the notion of context-independence when it came not only to the meanings of words and expressions; but also to the truth conditions of statements (or sentences). Indeed Putnam argued that if we have one, then we must also have the other. That is, the contextuality of meaning determines the fact that truth conditions must also be contextual in nature.

[Think here of Putnam’s well-known “cherry on the tree” example.]

Putnam argued:

“[] Wittgenstein and [J.L.] Austin well before us, would argue that sentences do not normally have context-independent truth conditions. It’s the meaning of the sentence or the words plus the context that fixes the truth conditions.”

Putnam meant that we can’t even begin to “fix the truth conditions” of words or sentences if we haven’t already fixed the meanings of those words or sentences. And that fixing of meaning will be a contextual matter.

So we must move from the

context-dependent meaning of the word “cat” and the whole sentence “The cat is on the mat”

to the

context-dependent truth conditions of the sentence “The cat is on the mat”.

Indeed we can’t even have a meaning (or Fregean sense) of the word “cat” unless we also have the intension of the sentence “The cat is on the mat” (at least according to Gottlob Frege’s context principle).

As with salient or relevant causal facts, we must also determine which truth conditions to focus upon. (Think again of Putnam’s “cherry on the tree” example.)

Not only that: according to Alfred Tarski’s Convention T, truth conditions are simply the named sentences once disquoted. Thus:

(T) S is true iff p.

Or:

(T) The sentence “Snow is white” is true iff snow is white.

All this can be summed up in the following way:

(i) If the truth conditions are the disquotation of the former named sentence, and that sentence requires a meaning that is context-dependent,

(ii) then it follows that the truth conditions (or simply the disquoted sentence) will also be context-dependent.

So truth conditions are not only dependent on the context of the meaning of the sentence “Snow is white”; but also on the context of the truth condition snow being white (or white snow).

(This isn’t, however, a choice we can make with Convention T.)

The Philosophical Formalisers

Hilary Putnam believed that one of the main reasons for the denial of context-dependence (or context-sensitivity) was the desire to make philosophy (or at least its semantics) more scientific and logical in nature. The Formalisers wanted to secure the “determinacy of sense or meaning” and the objectivity of language as a whole (see here). As Putnam put it:

“[P]hilosophy stands almost entirely apart from [linguistics, semantics, and lexicography], giving much too much significance to ideal language, mathematical logic and all that.”

In the first half of the 20th century many philosophers in the analytic tradition (at least, roughly, from 1905 to 1940 — see ‘Ideal Language’) virtually ignored work in linguistics, semantics and, most definitely, in lexicography. Even P.F. Strawson (1909–2006) — who was one of the first to reject the ideal of an ideal language and even its possibility (see here) — didn’t spend much time on linguistics and semantics.

These formalising philosophers were dealing primarily with what they believed to be abstract entities (such as senses, meanings and propositions). They did so with the tools of logic. Thus it’s hardly surprising that such philosophers had no time at all for linguistics and semantics. To think that a linguist could have told them the sense or proposition (as it were) behind a word or sentence would have seemed outrageous (or ludicrous) to them. Linguistics and semantics are largely empirical disciplines (or so it seemed to such philosophers); whereas philosophy of language and logic were a priori disciplines which dealt with what must be taken as a Platonic realm (or Frege’s Third Realm). This was even the case when such philosophers weren’t Platonists in general terms — i.e., when it came to ethics, other areas of metaphysics, etc.

The antipathy towards the ideal of an ideal language, on the other hand, was neatly expressed by Putnam himself in the following passage:

“I think that we still suffer from the idea that formalising a sentence tells you what it ‘really’ says. Perhaps we are now doing something similar with Chomskian linguistics.”

More broadly, it’s not just arrogant when a philosopher tells us “what we really mean”: it’s also wrong. It can’t be done. What such philosophers really told us (if they told us anything about our actual meanings) is what they believed we should have said or meant. And that hidden normativity (i.e., within their pronouncements) would have depended on the prior ontological and logical commitments of the philosophers concerned.

All that said, it’s now worth stating that poststructuralists, structuralists, postmodernists, literary theorists (as well as other kinds of “theorist”) etc. were — and still are — just as guilty of all this as any early-20th-century analytic philosopher. Such (as it were) non-analytics might have gone about it in different ways (i.e., they didn’t and don’t employ logic or the technical terms/devices of analytic philosophy) but they were — and still are — interpreting (sometimes very freely) what laypersons say and believe.

Still, let’s stick to analytic philosophy.

Now take the case of Bertrand Russell’s well-known ‘On Denoting’, which was first published in 1905.

Bertrand Russell is still widely known for once telling us what we (or at least philosophers) really mean when we use the words “The king of France is bald”. Yet, arguably, what Russell really meant when he attempted to (as it were) improve that sentence is simply tell us that we’re making philosophical and logical mistakes when we use it. Alternatively, Russell believed that philosophers and laypersons (when uttering “The king of France is bald”) were committed to things which they didn’t realise they were committed to. Thus Russell was telling us what we should say and also what we should be logically and/or philosophically committed to.

That said, Russell wasn’t telling folk that they actually are (i.e., consciously) committed to the existence of bald French kings, etc. And, the argument here is, Russell certainly wasn’t telling folk what they really meant.

In most cases (though not all), if people had wanted to say something else by what they said, then they would have said something else.

Would we say, for example, that when a young child states that “4 + 2 = 7” that he really meant to say “4 + 2 = 6”? No — the child was simply doing faulty arithmetic. Similarly, what if an adult says that “Jim is a shit” and a philosopher says that he really meant to say “Jim is a bad person”? Perhaps he should have said “Jim is a bad person”. Yet the adult who said “Jim is a shit” still didn’t really mean Jim is a bad person; otherwise he would have said that and meant that.

The formalising of a sentence (whether by Russell or by anyone else) is thus a little like psychoanalysis. In my stereotype, the psychoanalyst tells us what our dreams (or our locutions) really mean; even though we don’t ourselves know what they really mean. Indeed, almost by definition, the psychoanalyst (in these cases at least) believes that we mustn’t (or can’t) really know what we mean by what we say (or what our dreams really mean).

This means that the psychoanalyst has skills (or so he/she believes) that we don’t have and is thus automatically entitled to tell us what we really mean by something or other.

So, who knows, perhaps the psychoanalyst is being normative too in that he’s not really telling us what we really mean.

Similarly, the formalising philosopher also tells people that (almost by definition) they can’t know what they really mean because laypersons haven’t got the philosophical and logical skills to fully know (or know at all) what they really mean.

It’s strange, then, that on this interpretation of what the formalising philosophers did, they were essentially being normative when it came to formalising our sentences. That is, they were telling what we should mean given the ontological and logical implications of what we do actually say. Not only that: the Formalisers believed that we should be ontologically and logically committed to things that we aren’t actually committed to.

This means that instead of discovering the deep truths about propositions and meanings, the Formalisers were really offering deep truths about themselves — or about what it was they were logically and ontologically committed to.

And, if that was indeed the case, then perhaps the Formalisers should have come clean and told everyone that this was what they were doing.

Another way to put all this is to agree with Wittgenstein and say that there are no deep — logical or otherwise — truths about what we say.

Wittgenstein

So is everything really on the surface when it comes to what we say and what we mean? (As Wittgenstein put it: “Nothing is hidden.”)

This meant (at least to Wittgenstein and others) that any depths there actually are belong to the minds of the philosophers who create those depths. Yet if they’re only illusory depths (“cast by the shadows of our language”), then we have good reasons to ignore what the philosophers tell us about what it is we really mean.

In that case, then, perhaps the aforementioned psychoanalysts should have cast their nets into the depths of the minds of these formalising philosophers and told us what they, not us, really mean.

Putnam then offered us an interesting and ironic take on these philosophical formalisers. Putnam said:

“I think part of the appeal of mathematical logic is that the formulas look mysterious — you write backward Es!”

[These formalising philosophers might have argued — if they were still around when Putnam stated these words — that Putnam’s analysis of what they do is psychologistic or even one large ad hominem.]

To add detail to Putnam’s remarks; as well as to include some off-road Wittgensteinian forays.

Can’t it be argued that the Formalisers believed that the use of mathematical logic automatically took them nearer to the truth about such matters? Yet just because mathematical logic is arcane and an extra-special specialism (indeed just because it’s also “mysterious” — with its “backward Es”), then does that automatically mean that it will be of value when it comes to discovering anything about the non-formal matters of philosophy?

[It’s worth mentioning an appositely titled book by Bertrand Russell - ‘Mysticism and Logic’ (1914).]

That said, logic may well help us in certain — or indeed many — ways. (It will help us formalise our problems for a start.) However, wouldn’t we reach a point at which it would be of no help whatsoever?

So was mathematical logic seen by such Formalisers as the strange and arcane symbols of ancient myths and religions were seen by people in ancient cultures? Indeed did the Formalisers see their logical symbols as the sacred keys required to take them into an otherwise impenetrable (though deeper) world?

No comments:

Post a Comment