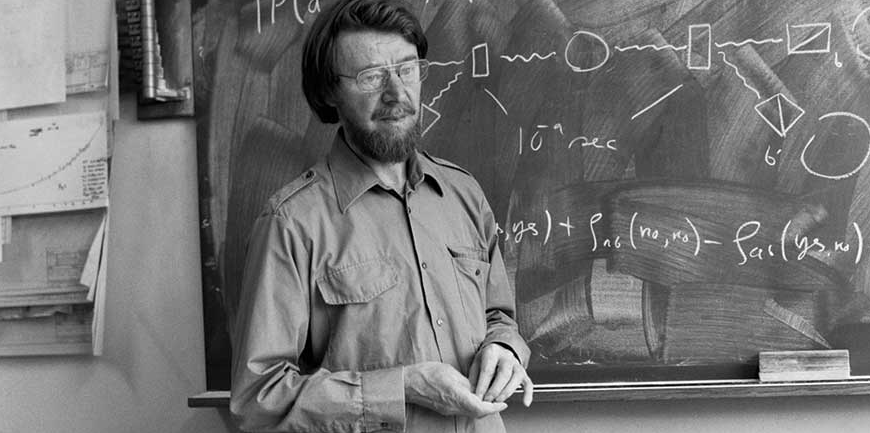

In certain respects at least, it’s odd that the physicist David Bohm (1917–1992) has often been recruited to various New Age, spiritual philosophy, and spiritual idealist camps. Why odd? It’s because Bohm was both a determinist and a scientific realist. Indeed, Bohm played down the importance of the “subjective” when it came to quantum mechanics (or quantum theory). Relatedly, Bohm was strongly against the positions of the Copenhagen school. Yet Copenhagenist positions are precisely those positions which New Agers, spiritual philosophers and spiritual idealists often positively quote and mention.

[Both the title and the content of the following essay are related to my previous piece, ‘The Weird Case of Wolfgang Pauli: Hardcore Positivist and ‘Mystic’’. See also the numerous publications, memes, etc. on “David Bohm the mystic” here, and on “David Bohm the spiritual scientist” here.]

Even some spiritual and religious fans of David Bohm’s ideas acknowledge that he was a determinist. Take, for example, Medium’s Gerald Baron, who states the following:

“[Bohm] didn’t like [] indeterminism — the uncertainty principle and other features of quantum behavior undermined physical determinism and opened the door to free will.”

Baron, on the other hand, wants to open the door to free will and the spirit (or soul). He wrote:

“[] I don’t agree that free will has nothing to do with good and evil. It seems central to the question. Even those strongly defending reductionism, physicalism and determinism point out that these accounts pose a great challenge to the idea of human agency and accountability.”

However, some of the earlier statements about Bohm should be qualified a little.

Perhaps Bohm only held that determinism and scientific realism reigned supreme… at the quantum level.

It must also be said here that there are some academics who state that Bohm wasn’t a determinist at all. [See here, and a paper called ‘Why Bohm was never a determinist’.] However, after reading some of these writings, the main two arguments are basically the following:

(1) Bohm wasn’t exclusively a determinist

(2) Bohm moved way beyond “old-style determinism” into other (more original and speculative) philosophical and scientific directions.

All that is true.

And, to get these points across again, let’s quote Wikipedia.

Wiki firstly states that Bohm was a determinist:

“Among his many contributions to physics is his causal and deterministic interpretation of quantum theory known as De Broglie–Bohm theory.”

Yet Wiki too stresses the Bohm-wasn’t-an-old-style-determinist idea when it continues with these words:

“Bohm’s aim was not to set out a deterministic, mechanical viewpoint, but to show that it was possible to attribute properties to an underlying reality, in contrast to the conventional approach.”

Although this isn’t a place to go into detail, Bohm clearly wasn’t against determinism. However, he did offer us his very own brand of determinism. That is, in Bohm’s new cosmic reductionism, we don’t have “the reduction of everything to hard particles” (or to whatever). Instead, we have a reduction of everything to a holistic “underlying [cosmic] reality”.

Thus, paradoxically, Bohmian holism can itself be seen as a spiritual kind of reductionism. So it’s worth saying here (i.e., for explanatory purposes) that Bohm’s spiritual reductionism is much like the Donald Hoffman’s reduction of literally everything down to what he calls “conscious agents” — or to the cosmic consciousness of “the One”. [See note 1, and my ‘What Is a ‘Conscious Agent’? Donald Hoffman, Please Tell Me’.]

Anyway, what’s important here (at least in the context of this essay) is that there seems to be a clash between Bohm’s determinism and scientific realism, and the “spiritual” and consciousness-first aspects of his work which many of his fans focus upon.

David Bohm as Mystic

There are elements of both Bohm’s science and his philosophy which spiritual idealists, New Agers and spiritual philosophers can — and have — taken hold of. Indeed, there are many reasons to recruit Bohm into the spiritual camp. (Bohm’s collaboration with the “spiritual figure” Jiddu Krishnamurti is just one single example.) However, this isn’t also to say that Bohm’s take on things is identical to anything advanced by any of the aforementioned individuals.

For a start, hardly any of these spiritual fans of Bohm are actual scientists. What’s more, it’s clear that they tend to know very little physics. Indeed, the physics they do know is used almost exclusively to advance their spiritual views.

This means that ideas and passages within Bohm’s writings can indeed be stressed by spiritual idealists, spiritual philosophers and New Agers. Yet, in terms of this essay at least, Bohm was still a determinist, and he was still a scientific realist. This can be seen as meaning that the aforementioned commentators are cherry picking positions from Bohm. Alternatively, perhaps they can argue that there’s some kind of harmony between Bohm’s determinism/realism, and his “spiritual ideas”.

It’s also worth stating here then when Bohm did discuss these extra-scientific (or spiritual) elements, he did so in a prose style that’s very hard to understand. (Perhaps I should simply say that I personally find it very hard to understand.)

There may be a very good and convincing reason for this opacity in Bohm’s prose.

For example, Bohm once stated the following:

“[M]etaphysics is an expression of a world view [] thus to be regarded as an art form, resembling poetry in some ways and mathematics in others, rather than as an attempt to say something true about reality as a whole.”

So can’t we immediately respond by stating the following? -

Bohm’s metaphysics, and perhaps even parts of his physics, are an expression of a world view and thus an art form, resembling poetry [or a spiritual religion] in some ways and mathematics in others.

More generally:

Bohm’s metaphysics, and perhaps even parts of his physics, are not true about reality as a whole.

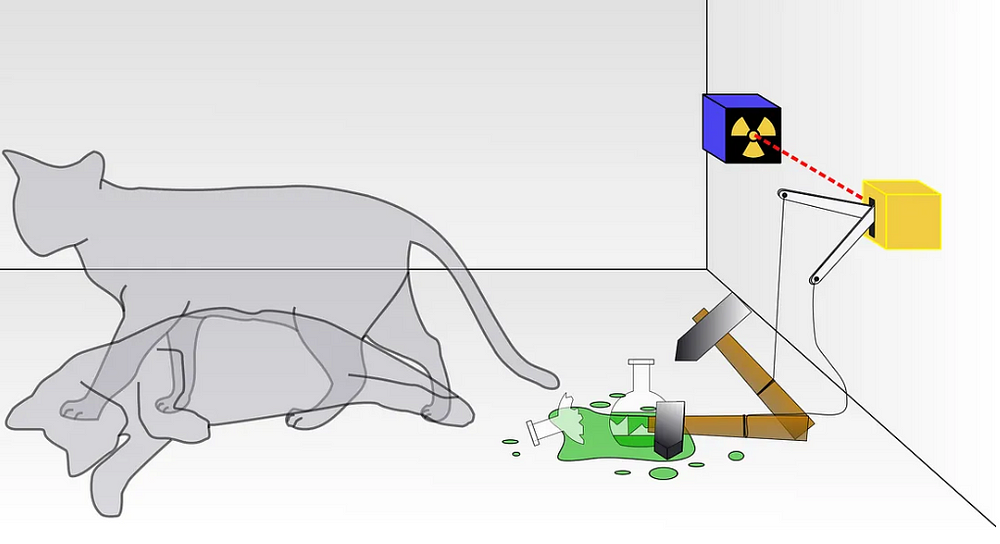

Relevantly, all this stuff about (as it were) artistic metaphysics seems to work in favour of Bohm being a “mystic”. However, like Schrödinger [see note 2], Bohm made a point of separating and distinguishing his actual physics from his philosophical and spiritual views. So, in simple terms, you won’t find much philosophy or spirituality in Bohm’s early (technical) papers on physics. However, you will find such things in the books which Bohm wrote in his later years (i.e., from 1976 onward).

Bohmian Holism

More particularly, New Agers, idealists and spiritual philosophers focus (or even fixate) on Bohm’s holism, as well as his parallel stress on non-locality. (It’s worth noting that Bohm’s non-locality goes way beyond quantum non-locality.) Yet, in a sense, these positions seem to clash with Bohm’s scientific realism and determinism. Perhaps, more accurately, they may not clash with anything Bohm himself actually held in his philosophy and his science. However, they most certainly do clash with what many New Agers, spiritual philosophers, etc. believe. And that fact partly explains why such people cherry pick Bohm’s positions and statements, and artfully ignore his realism, determinism, and his strong belief in scientific “objectivity” (i.e., against “subjectivism”).

In terms of holism, take this passage from Bohm’s book Wholeness and the Implicate Order:

“[T]he world is assumed [by most physicists?] to be constituted of a set of separately existent, indivisible, and unchangeable ‘elementary particles’, which are the fundamental ‘building blocks’ of the entire universe [].”

And here’s Bohm writing in 1980 about his very own alternative:

“The new form of insight can perhaps best be called Undivided Wholeness in Flowing Movement. This view implies that flow is in some sense prior to that of the ‘things’ that can be seen to form and dissolve in this flow.”

[Recall Bohm’s earlier words: “[M]etaphysics is an expression of a world view [] thus to be regarded as an art form, resembling poetry in some ways [].]

Although these aspects of Bohm’s philosophy and science won’t be discussed in this essay, it’s worth noting that nothing in the first passage above (i.e., not the passage about the “Undivided Wholeness in Flowing Movement”) needs to be tied to anything spiritual, supernatural, “transcendent” and/or “mystical”. In fact, most physicists accept non-locality, the importance of fields, etc. without feeling the need to endorse all the many additional spiritual ideas and commitments — all of which go way, way beyond the physics.

In terms specifically of the philosophical position of relationalism.

Bohm’s idea that that phenomena aren’t reducible to fundamental particles (or even to single determinate and circumscribed states or events) isn’t that different to the philosophical relationalism of Carlo Rovelli or the ontic structural realism of James Ladyman. [See note 3.]

However, let’s now move onto Bohm’s determinism and his rejection of what many physicists have called “subjectivism”. [See note 4.]

David Bohm’s Determinism

The Northern Irish physicist John Stewart Bell gave a historically interesting and clear account of David Bohm’s determinism in the following passage:

“[I]n 1952 I saw the impossible done. It was by David Bohm. Bohm showed explicitly how parameters could indeed be introduced, into nonrelativistic wave mechanics, with the help of which the indeterministic description could be transformed into a deterministic one.”

Elsewhere, Bell wrote:

“Bohm’s 1952 papers on quantum mechanics were for me a revelation. The elimination of indeterminism was very striking.”

Of course, I now need to quote Bohm himself.

Oddly, it’s hard to find any explicit passages on this subject in Bohm’s own works. Instead, it seems that it was nearly all said with his early mathematics. However, he did write the following words (as found in his paper ‘A Suggested Interpretation of the Quantum Theory in Terms of ‘Hidden’ Variables’) in 1952:

“The usual interpretation of the quantum theory is based on an assumption having very far-reaching implications, ~i.e., that the physical state of an individual system is completely specified by a wave function that determines only the probabilities of actual results that can be obtained in a statistical ensemble of similar experiments. This assumption has been the object of severe criticisms, notably on the part of Einstein, who has always believed that, even at the quantum level, there must exist precisely definable elements or dynamical variables determining (as in classical physics) the actual behavior of each individual system, and not merely its probable behavior. Since these elements or variables are not now included in the quantum theory and have not yet been detected experimentally, Einstein has always regarded the present form of the quantum theory as incomplete, although he admits its internal consistency.”

As is almost too obvious to state: spiritual idealists, New Agers and spiritual philosophers tend to stress indeterminism. [See here.] Indeed, they stress indeterminism not only at the quantum level, but at the “classical” level too. Yet here is Bohm — at least according to Bell — not only offering an alternative to indeterminism at the quantum level, but actually attempting to eliminate it…

Talk about “the clockwork universe” so often criticised by New Agers and spiritual philosophers. [See note 5.]

That’s Bohm (if partly via Bell) on determinism.

So what about Bohm’s stance against (as it’s often been called) “Copenhagenist subjectivism”?

The Observer and Scientific Subjectivism

John Bell continued:

“More importantly, in my opinion, the subjectivity of the orthodox version, the necessary reference to the ‘observer,’ could be eliminated.”

In more detail, Bell wrote:

“But more important, it seemed to me, was the elimination of any need for a vague division of the world into ‘system’ on the one hand, and ‘apparatus’ or ‘observer’ on the other."

It’s precisely the “observer” which New Agers, spiritual idealists and spiritual philosophers have stressed. Yet Bohm attempted to eliminate the need to even mention the observer.

However, and as before with determinism, I now need to quote Bohm himself on realism. So here’s a passage from a letter to Karl Popper, which goes as follows:

“I certainly think that a realistic interpretation of physics is essential. […]”

That sentence just quoted, Bohm does then go on to play down (if only a little) his determinism:

“Firstly I am not wedded to determinism. It is true that I first used a determinist version of […] quantum theory. But later […] a paper was written in which we assumed that the movement of the particle was a stochastic process. Clearly that is not determinism. […] The key question at issue is therefore not that of determinism vs. indeterminism [it’s one of realism vs. subjectivism]. I personally do not feel addicted to determinism, but I am ready to consider deterministic proposals […] if they offer some useful insights.”

This isn’t a case of Bohm rejecting determinism.

Instead, it’s a case of Bohm (as stated earlier) going beyond old-style determinism, but also accepting determinism if it “offer[s] some useful insights”. Again, this isn’t a case of determinism vs indeterminism. It’s a case of determinisms-in-the-plural vs One Determinism.

All that said, it must be admitted that Bell’s earlier way of putting things can be read as working on behalf of some of the ideas of New Agers, spiritual philosophers and spiritual idealists. That’s because it seems to be an argument for the joint importance of “observer” and “system” — or even the philosophical fusion of observer and system.

However, that wasn’t what Bell was getting at.

Instead, Bell was stressing that the elimination of the observer was possible (i.e., at least in principle). Bell wasn’t arguing that the observer (or, as idealists put it, “consciousness”) and the (studied) system have a joint importance - let alone that they must be fused. In other words, Bohm was a realist (see here) who believed that the observer could be eliminated (or factored out) completely. Thus, the real quantum world could — at least in principle — be described in itself.

Consequently, this is a position that’s the exact antithesis of that of spiritual idealists, New Agers, and spiritual philosophers , all of whom stress the observer — or at least the consciousness of the observer.

Again, Bohm was a scientific realist, not an idealist. That said, it’s of course the case that in other areas Bohm did indeed stress consciousness. [See here.]

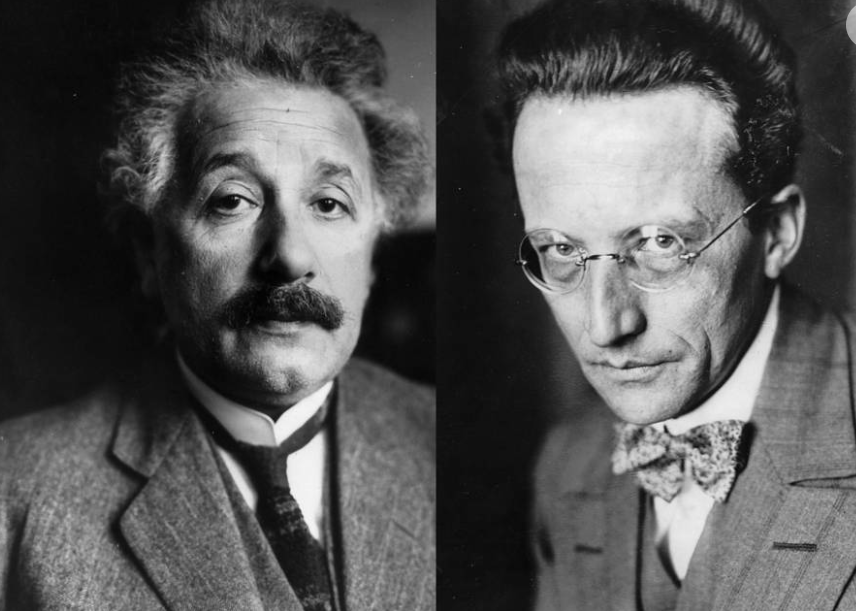

Einstein, Schrödinger and Bell on Determinism and Subjectivism

Albert Einstein is another physicist who’s often conscripted into the spiritual idealism, New Age and spiritual philosophy camps. Yet it’s well known that Einstein had problems with the Copenhagen interpretation, which is also often conscripted into the aforementioned camps!

Specifically, Einstein’s very own rejection of indeterminism and embrace of scientific realism is relevant here.

In 1949, Einstein wrote this often-quoted passage:

“I am, in fact, rather firmly convinced that the essentially statistical character of contemporary quantum theory is solely to be ascribed to the fact that this (theory) operates with an incomplete description of physical systems . [] [In] a complete physical description, the statistical quantum theory would [] take an approximately analogous position to the statistical mechanics within the framework of classical mechanics .”

Albert Einstein was at one with Erwin Schrödinger on many of these issues. That is, Schrödinger was also against “subjectivism in physics”, which is precisely what New Agers, spiritual philosophers, etc. stress and propagate.

Schrödinger (in 1926), for example, stated that Bohr’s “approach to atomic problems [] is really remarkable”.

Why did Schrödinger state that?

He continued:

“He is completely convinced that any understanding in the usual sense of the word is impossible.”

This is Schrödinger stressing scientific realism. In other words, he was arguing against the subjectivism and even (as some had it) idealism of the Copenhagenists.

In detail.

The “understanding” which Schrödinger demanded, could be had without stressing the observer or consciousness. In other words, what physicists had achieved at the “classical” level, Schrödinger believed physicists could achieve at the quantum level too.

In addition, New Agers, spiritual idealists and spiritual philosophers are also very keen on Niels Bohr’s notion of complementarity. Indeed, such people (just like postmodernists) apply it to almost everything under the sun. (This is much in the way that Gödel incompleteness theorem is applied to every under the sun. [See the non-ironic ‘Incompleteness explains everything. Kurt Gödel’s legacy’.])

New Agers, spiritual idealists and spiritual philosophers are keen to mention and quote Schrödinger too.

Yet here’s Schrödinger rejecting complementarity. He wrote:

“Old-age dotage closes my eyes towards the marvelous discovery of ‘complementarity’. So unable is the good average theoretical physicist to believe that any sound person could refuse to accept the Kopenhagen oracle [i.e., Niels Bohr].”

Schrödinger then went into detail with the following words:

“[M]ost of my friendly (truly friendly) nearer colleagues [] have formed the opinion that I am — naturally enough — in love with ‘my’ great success in life (viz., wave mechanics) reaped at the time I still had all my wits at my command and therefore, so they say, I insist upon the view that ‘all is waves’.”

If we now move forward in time to John Bell again.

Bell argued against the stress on the the split between what he called “the observer” and “the system”. He wrote:

“[T]he words ‘quantum mechanical system’, which can have an unfortunate effect on the discussion.”

On one contextless reading at least, Bell’s way of putting things can be seen to actually work on behalf of a consciousness-first position. In other words, that passage seems to imply the joint importance of the observer and the system.

However, that wasn’t what Bell was getting at.

Bell was actually advocating for the elimination of the observer. He wasn’t arguing that the observer (or, as idealists put it, “consciousness”) and the system have a joint importance either — let alone that they can be philosophically fused. Instead, Bell believed [see here] that the observer could be eliminated (or factored out) completely. Thus, the quantum world could — at least in principle — be described in itself…

And that is scientific realism.

Conclusion

All the physicists which New Agers, spiritual philosophers and spiritual idealists quote and mention (such as Einstein, Schrödinger, Heisenberg, Pauli and even Bohm) don’t neatly (or even at all) fit into their own spiritual worldviews. Still, artfully-selected lines (i.e., rarely full passages) from these supposedly “religious” or “spiritual” physicists are still quoted in out-of-context… contexts. What’s more, the same lines are quoted very many times, and they regularly appear as memes on social media. [See note 6.]

Notes:

(1) Take this comment on Donald Hoffman’s own brand of reductionism:

“You pointed out [Donald Hoffman’s] strawmanning of reductionism [] [W]hat is his theory of conscious agents purportedly explaining space time, particles, and scattering amplitudes if it isn’t reductionist?) [].”

This passage can be found after a YouTube video interview called ‘What is Reality’, in which the philosophers Keith Frankish and Philip Goff interview Donald Hoffman.

(2) According to one biographer (i.e., Walter Moore, in his Schrödinger: Life and Thought),

“the philosophy of Schrödinger at this time does not appear to have been influenced by his physics”.

In addition, Schrödinger

“often said that one cannot derive philosophical conclusions from physics”.

(3) See my ‘Carlo Rovelli’s Relationalism — as Defended in His Book, Helgoland’, ‘Carlo Rovelli’s Relational Quantum Mechanics’, and my ‘Every Subatomic Particle Must Go’ (which is on James Ladyman’s ontic structural realism).

(4) The term “subjectivism” isn’t actually a synonym of “idealism”, but it’s often been used in such a way.

(5)

Spiritual philosophers and New Agers play down determinism at the physical or scientific level. Yet, at the very same time, some of them also play up God’s — or “the One’s” — power over every aspect of our lives and the universe. Indeed, such “spiritual” and religious people can even be deemed to be fatalists.

(6) Many spiritual philosophers, New Agers and spiritual idealists seem to have learned a lot from political activists on social media. That is, in the way in which they rely heavily on memes, titillating images (often psychedelic images of people looking up at the stars), catchy slogans, copied-and-pasted quotes from selected physicists, etc.

No comments:

Post a Comment