And also waste our time? More accurately, is it logically possible that a fixation on logical possibilities could mislead us and/or waste our time?

The following essay will mainly be considering David Chalmers’ paper ‘Absent Qualia, Fading Qualia, Dancing Qualia’. However, absent, fading and dancing qualia won’t actually be tackled in detail. Instead, the subject of logical possibility will be discussed (as it were) in the abstract.

There is one bizarre passage (at least when taken out of context) in Chalmers’ aforesaid paper which summarises everything that will be tackled here. (It’s broken up into three parts.) It goes as follows:

“[W]e have established that if absent qualia are possible, then fading qualia are possible; if inverted qualia are possible, then dancing qualia are possible.”

However:

“But it is implausible that fading qualia are possible, and it is extremely implausible that dancing qualia are possible. It is therefore extremely implausible that absent qualia and inverted qualia are possible.”

Chalmers concludes:

“It follows that we have good reason to believe that the principle of organizational invariance is true, and that functional organization fully determines conscious experience.”

That passage has it all!

It displays a (as it were) fixation with logical possibility, along with the strong belief that considering (or analysing) such possibilities leads to very real and important philosophical conclusions. Indeed, perhaps, non-philosophical conclusions too!

Why Fixate on Logical Possibilities?

It’s not only the paper ‘Absent Qualia, Fading Qualia, Dancing Qualia’ which focuses so much on logical possibility. David Chalmers’ well-known and brilliant book The Conscious Mind also seems to introduce one logical possibility or another on almost every page. Specifically, in that book Chalmers discusses “an angel world”, “flying telephones”, “ectoplasm”, and a monkey who writes Hamlet. Admittedly, most of these logical possibilities are of little (philosophical) interest to Chalmers.

So why is that?

It’s only partly because such logical possibilities are hugely improbable. However, the main reason why Chalmers has no deep interest in them is that they don’t help him philosophically.

The logical possibilities of an angel world, flying telephones, ectoplasm, and a monkey who writes Hamlet have just been mentioned. However, and as many readers will know, it’s primarily (philosophical) zombies which Chalmers (as it were) specialises in. And it’s these logically-possible beings who (or is it which?) help him philosophically.

So despite all the logical possibilities which Chalmers does discuss, almost his entire philosophical project is motivated by it being (to use his own words)

“logically possible that a *physical* replica of a conscious system might lack conscious experience”.

Thus, all the other logical possibilities Chalmers discusses are but a means to add meat to that specific logical possibility. And that specific logical possibility, in turn, serves the purpose of showing readers that (to use Chalmers’ own words) “materialism is false”. In other words, if it’s “logically possible that a physical replica of a conscious system might lack conscious experience”, then materialism can’t be true…

Or so the argument goes.

[See note 1 for the full argument.]

To quote Chalmers himself:

“I am not the first to use the argument from logical possibility against materialism. Indeed, I think that in one form or another it is the fundamental anti-materialist argument in the philosophy of mind.”

So citing logical possibilities isn’t just another philosophical tool — it is (arguably) the philosophical tool to fight materialism. (Perhaps much more too.) Yet Chalmers also suggests that we shouldn’t get “too worried about odd things that happen in logically possible worlds”. That said, he then immediately takes that back by adding that “there is room to be perturbed by what is going on”.

In more detail.

Chalmers and certain other philosophers require logical possibilities in order to advance their case against materialism. What’s more, their arguments only work if one deeply considers all sorts of strange logical possibilities. Of course, this isn’t to say that materialists (as well as other kinds of philosopher) don’t themselves rely on (or simply use) logical possibilities in various ways. [See Joseph Levine’s words quoted in note 2.] However, they don’t do so nearly so often as philosophers like David Chalmers.

Now let’s forget anti-materialism and speak in broader terms.

When a philosopher cites various logical possibilities, all sorts of philosophical positions become available… or become possible. That’s primarily because once a given philosopher sets a particular logical possibility among the pigeons, then it’s surely the duty of other philosophers to tackle that logical possibility. However, if they don’t do so, then surely (some philosophers may argue) they’re philosophical (as it were) philistines.

To repeat. Chalmers’ main use of logical possibilities is to argue against materialism. That said, in the paper ‘Absent Qualia, Fading Qualia, Dancing Qualia’, Chalmers’ main purpose it to show his readers that (as already quoted) “functional organization fully determines conscious experience”.

[On the surface at least, that last quoted claim seems to work against Chalmers’ anti-materialism. However, that issue can’t be tackled in this essay either. See note 3.]

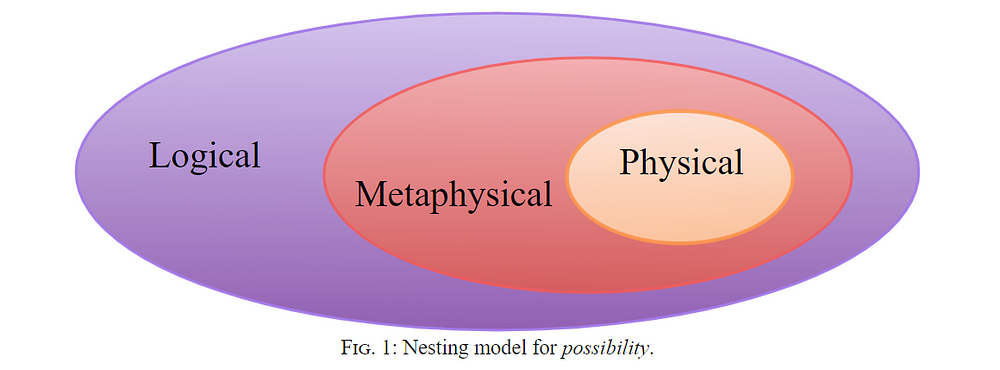

Not All Logical Possibilities Are Equal

David Chalmers argues that all the logical possibilities he discusses are “intelligible”. However, he also believes that some of them are “implausible”. In more detail, Chalmers states the following:

“Mere intelligibility does not bear on this, any more than the intelligibility of a world without relativity can falsify Einstein’s theory.”

Chalmers doesn’t believe that such logical possibilities are implausible because they’re merely… logical possibilities. Instead, it’s only specific logical possibilities which Chalmers finds implausible.

Chalmers also states (in one place) that the “hypotheses here are coherent, but there is little reason to embrace them”. In other words, coherency alone won’t force his readers to embrace such hypotheses. Yet elsewhere Chalmers also says that

“the question is not whether it is plausible that zombies could exist in our world, or even whether the idea of a zombie is a natural one; the question is whether the notion of a zombie is conceptually coherent”.

To Chalmers, “the notion of a zombie” is indeed “conceptually coherent”.

What’s more, the notion of a philosophical zombie has many other philosophical things going for it.

So Chalmers does argue that a lot can be derived from something’s “intelligibility”. This means that Chalmers stance on these “scenarios” (or logical possibilities) doesn’t entirely depend on mere intelligibility — it also depends on where these scenarios lead.

Basically, then, Chalmers isn’t questioning all modal speculations (or the use of thought-experiments) — clearly not! To Chalmers, it depends on which precise logical possibility he’s discussing.

Chalmers goes further on the subject of logical possibility.

He also believes that some of possibilities he discusses could (which is another modal term) also be “actual”. Yet this isn’t entirely clear because — as already stated — Chalmers does admit that some (even many) of the logical possibilities he discusses are “implausible”. That said, Chalmers must believe that such logical possibilities still need to be philosophically analysed (or dissected) in order to justifiably conclude that they’re implausible.

What’s more, even when logical possibilities can’t (or don’t) lead to actualities, then they may still be worth discussing — at least from a philosophical point of view.

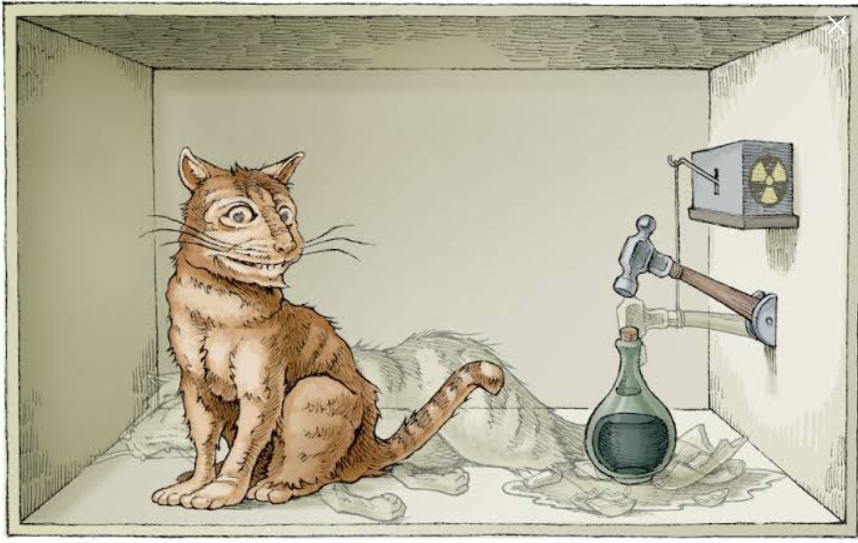

Schrödinger’s Cat

David Chalmers discusses Erwin Schrödinger's famous thought-experiment about a cat in a box (i.e., Schrödinger’s cat). He does so in order to compare what he’s doing to what Schrödinger did way back in 1935.

Chalmers writes:

“Perhaps it is useful to see these thought-experiments as playing a role analogous to that played by the ‘Schrodinger’s cat’ thought-experiment in the interpretation of quantum mechanics.”

Chalmers then explains this analogous role in the following way:

“Schrödinger’s thought-experiment does not deliver a decisive verdict in favour of one interpretation or another, but it brings out various plausibilities and implausibilities in the interpretations, and it is something that every interpretation must ultimately come to grips with.”

Chalmers finally concludes:

“In a similar way, any theory of consciousness must ultimately come to grips with the fading and dancing qualia scenarios, and some will handle them better than others. In this way, the virtues and drawbacks of various theories are clarified.”

Schrödinger’s thought-experiment never became an actual experiment. That is, it has never been carried out… on a cat. In addition, Schrödinger himself never believed that a cat could be both alive and dead at one and the same time. On the other hand, other physicists — such as the theorists of many worlds — do believe that. (Such physicists believe that the possible alive-and-dead-cat superposition would be actual if the experiment were ever successfully carried out.)

In basic terms, Schrödinger intended his thought-experiment to illustrate the bizarre nature of the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics. Indeed, Schrödinger took it to be a reductio ad absurdum.

So Schrödinger was categorically against the Copenhagen interpretation, whereas Chalmers sees himself as considering various logical possibilities, and (as it’s often put) seeing where they all lead.

Oddly enough, Schrödinger can be seen as actually arguing against taking outlandish possibilities (in this case, quantum superpositions) seriously. Yet, ironically, he concocted a though-experiment (which includes the logical possibility of a cat being both alive and dead) to advance his case.

All that said, it can now be acknowledged that both Schrödinger’s thought-experiment and Chalmers’ many logical possibilities do indeed (as Chalmers puts it) “bring out various plausibilities and implausibilities”.

Philosophically Necessary Logical Possibilities?

It’s also odd that Chalmers states that

“any theory of consciousness must ultimately come to grips with the fading and dancing qualia scenarios”

when the vast majority of theories of consciousness haven’t done so. Indeed, many theorists and philosophers of consciousness have hardly considered these “scenarios” at all. That’s primarily because the interest in fading, inverted and dancing qualia has been an obsession of (only certain) analytic philosophers for only a limited period of philosophical history. (Roughly, since 1982 and onward. See here.)

So can we now also conclude that many theorists and philosophers of consciousness don’t consider inverted, dancing and fading qualia because they don’t place such a high premium on the status of (mere) logical possibilities?

Alternatively, perhaps it’s just these logical possibilities (i.e., inverted, dancing and fading qualia) which they don’t care too much about.

Finally, it does seem a little over the top when David Chalmers states that “any theory of consciousness must ultimately come to grips with the fading and dancing qualia scenarios”. Indeed, is that even the case when it comes to Chalmers’ famous and endlessly-discussed phil-zombies?

Notes:

(1) David Chalmers’ precise argument is the following:

“ 1. In our world, there are conscious experiences.

2. There is a logically possible world physically identical to ours, in which the positive facts about consciousness in our world do not hold.

3. Therefore, facts about consciousness are further facts about our world, over and above the physical facts.

4. So materialism is false.”

2) Is there no escape from logical possibility? The American philosopher Joseph Levine believes so — at least in the case of qualia. He wrote:

“Would could just deny that what is conceivable is possible. [] But now we have an answer as well to the multiple realizability argument. After all, what makes us so confident that QR [a particular “property of experience”] could be realized in a variety of different ways? Isn’t it just the same conceivability we appealed to in the conceivability argument?”

(3) David Chalmers’ mitigated functionalism is well summed up by the German philosopher Thomas Metzinger:

“Although the appropriate functional states are *nomologically sufficient* for conscious experience, they need not be *constitutive* of conscious experience. This leads to an interesting position which Chalmers calls non-reductive functionalism*, which is compatible both with property dualism and with some forms of physicalism.”

No comments:

Post a Comment