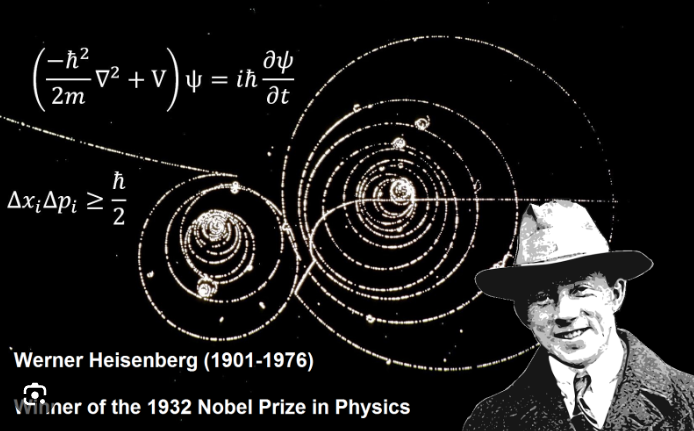

“Browse through any bookshop’s new-age section [] and you’ll find wild claims confidently asserted about the uncertainty principle [or observer effect], such as that its implications are ‘psychedelic’ and that it heralds ‘cultural revolution.’ [] Consider the following conversation, published in *American Theatre*, between the well-known theatre director Anne Bogart and Kristin Linklater, the noted vocal coach:

Linklater: ‘Some thinker has said that the greatest spiritual level is insecurity.’

Bogart: ‘Heisenberg proved that. Mathematically.’

Linklater: ‘There you are.’

[] The uncertainty principle sprang from a purely mathematical approach to atomic physics, where it has a well-defined and highly restricted scope of applicability.”

— — Robert P. Crease [See source here.]

Many idealists, New Agers and spiritual commentators (at least those who mention the subjects which will follow) have often focused on the “observer effect” in quantum mechanics. (This is the case even when they don’t actually use that precise technical term.) They do so because they believe that it strongly ties consciousness to reality (or reality to consciousness). Indeed, such people also believe that the observer effect makes reality a product (or an effect) of consciousness.

When the observer effect is discussed, the word “mysticism” is often used too.

The word “mysticism” is, admittedly, vague.

The Copenhagenists, for one, were often accused of “mysticism” in an entirely negative manner. However, New Agers and spiritual commentators use this term positively about the very same physicists.

So why was the word “mysticism” used?

It was primarily for “introducing consciousness into physics”. [See here.]

The other main sense of “mysticism” (i.e., in this context) refers to physicists being influenced (or inspired) by mystical literature of by Eastern religions.

New Agers, spiritual commentators and idealists believe that such physicists noted the observer effect (as well as the uncertainty principle, entanglement, complementarity, etc.) precisely because of their prior knowledge of mystical or eastern literature. The New-Age idea is that such physicists also believed that Eastern ideas provided a good philosophical explanation of such issues within physics.

Yet the vast majority of the physicists who’ve accepted and endorsed the observer effect, entanglement, etc. have done so without ever having read a single word of mystical and/or Eastern literature. Of course, New Agers, spiritual commentators and idealists will (or simply might) respond with the following words:

That doesn’t matter. Non-mystical physicists are still tapping into phenomena which ancient religions have known about for millennia.

What ancient religions understood can only tangentially, analogically and with a very-large amount of artistic license be tied to the theories and ideas of quantum mechanics. After all, anything can be tied to anything if you try hard enough. (This was certainly the case when, for example, Carl Jung’s notion of synchronicity was tied to quantum-mechanical theories.)

In any case, it can be argued that this mysticism best manifested itself in the way in which a very-small number of physicists attempted to “unify mind and physics” in the first half of the 20th century.

Mystical Physics… or Simply Mystical Physicists?

“[W]hen a scientist says that he/she believes in god, believers take it to mean that god must be true — because it’s coming from the seekers of objective truth. Not that the believers really needed this validation (they were believers already), but belief is all about post-rationalization and confirmation bias. Hence, ‘validation’ from a few scientists goes a long way. [] They conveniently forget that a majority of scientists do not believe in god.”

— — — The Other Millennial [Source here.]

In his paper ‘Mysticism in quantum mechanics: the forgotten controversy’, the academic Juan Miguel Marin tells us that Hermann Weyl and Wolfgang Pauli

“were both immersed in mysticism, searching for a way to unify mind and physics”.

Some readers may ask why the project of unifying mind and physics is automatically deemed to be a case of “mysticism”. So perhaps this isn’t an automatic thing at all. Yet when it comes to New Agers, spiritual commentators and idealists, it often does seem as if they believe that there’s some kind of automatic link here.

In any case, when Hermann Weyl and Wolfgang Pauli attempted to unify the mystical (if not the mind) with physics, they weren’t doing neuroscience — or, indeed, any kind of science. They had nothing to say about the brain itself. What’s more, physics was only tangentially and analogically linked to this attempted unification of the mind (seen mystically) with physics.

Basically, then, Weyl and Pauli were essentially doing philosophy when they attempted to unify mind and physics.

Juan Miguel Marin also asks us the following question about Arthur Eddington and Erwin Schrödinger:

“Did their shared mysticism have a role to play in whatever insights they gained or mistakes they made? [].”

The answer to that question may well be “Yes”. After all, this is nothing less than the context of discovery. And contexts of discovery are real things.

By way of a comic illustration.

In ‘The Relationship Diremption’ episode of The Big Bang Theory sitcom, the “nerd” character Sheldon Cooper admitted that he “didn’t seek out string theory”. Instead, string theory “just hit [him] over the head one day”.

So what did Mr Cooper mean by that? The following:

“A bully chased me through the school library and hit me over the head with the biggest book he could find.”

That book was on string theory. And Sheldon Cooper was hooked on string theory from that day on.

This fictional account is obviously a joke. However, it has an element of sociological and psychological truth. Indeed, it’s part of the context of discovery. Of course, the context of discovery-context of justification distinction may well be a little too neat and tidy for some people. Yet it still has its large degree of truth, its value, and its uses.

So if we return to the non-fictional physicists Eddington and Schrödinger.

It’s certainly possible that Eddington and Schrödinger might not have had their “insights” had they not also been influenced by mystical literature.

That said, questions can still be asked about this.

At the very least, mystical literature would have had a very minimal role to play on these physicists’ actual theories in physics (i.e., the technical stuff they had published in physics journals).

Take the specific case of Schrödinger.

According to the writer Walter Moore (in his Schrödinger: Life and Thought),

“the philosophy of Schrödinger at this time does not appear to have been influenced by his physics”.

In parallel, Schrödinger also

“often said that one cannot derive philosophical conclusions from physics”.

Yet even when biographical information is included (Marin relies heavily on much context-of-discovery stuff, and Walter Moore obviously mentions it too), it’s still very difficult to establish any concrete, important and relevant links between actual theories in physics and any “eastern” religious texts these named physicists might have read (i.e., at some point in their lives).

In any case, does it matter?

That is, are their genuinely and purely mystical elements embedded within the actual scientific theories of, say, Eddington and Schrödinger?

Alternatively, is all this stuff about physics-and-the-mystical made up of analogy, metaphor, biography, scientifically irrelevant contexts-of-discovery, wishful thinking, wild interpretations, tangential links and circuitous reasoning?

What’s more, the vast majority of New Agers and spiritual commentators who mention these ideas from quantum mechanics, and who also frequently drop the names of famous physicists, do so exclusively to advance their religious (or spiritual) ideas, causes and goals…

In other words, such New Agers and spiritual commentators have almost zero interest in physics qua physics.

[There’s a sizable number of writers here on Medium to whom all this applies. Deepak Chopra is one of that number.]

Does Consciousness Affect Reality?

Juan Miguel Marin also states the following:

“[I]n quantum mechanics, physicists’ observations can sometimes affect what they’re observing on a quantum scale.”

To put it strongly: that is simply false…

Or, rather, it’s only false if Marin’s words are read in a certain way. More particularly, it depends on how the word “observations” is read.

The way the general idea above is usually expressed (i.e., by New Agers, spiritual commentators, etc.) makes it seem as if consciousness alone literally affects physical reality.

At an extreme level, this would simply be a form of telekinesis.

The definition of the word “telekinesis” perfectly fits some of the things New Agers, spiritual commentators, and some idealists say about the observer effect. Thus:

“Telekinesis [], also known as Psychokinesis, is a hypothetical psychic ability allowing an individual to influence a physical system without physical interaction.”

Yet consciousness alone does not affect physical reality.

However, observations as they occur in physics can affect reality.

So now let’s tackle the notion of observation.

What Is a Scientific Observation?

One factor which may well seem idealist to some occurs when one scientist’s observation-based interpretation of an experiment (or experimental space) conflicts with another scientist’s observation-based interpretation of the very same experiment. However, there is no actual causal, telekinetic or otherwise affect on the physical world here. It’s simply a case of different scientists coming to different conclusions, formulating different theories (or interpretations), and even “seeing” different things. [See note 1 on Norwood Russell Hanson.]

The paragraph above can also be deemed to be an indirect reference to Niels Bohr’s notion of complementarity. For example, in one experiment (or observation), a particle is “observed” (or at least posited), and in another experiment, a wave is observed (or posited). That said, it’s usually the different experimental setups which generate the complementary results in these cases.

Again, there’s no literal (or purely) “mental impact” on the world here either.

Of course, observations and experiments (or measuring devices) can and do change what is observed. Yet that’s not what New Agers, idealists and Juan Miguel Marin are attempting to tell us.

To be crude.

If a physicist is fumbling around with a given experimental space, then that will affect that space. However, that has little to do with his consciousness — free of all physical manipulations — affecting the world.

Of course, some believers in the Copenhagen interpretation may argue that we have no right at all to say anything about the world as it is free of minds, experiments, manipulations, etc. There may be no problem with that position. However, such people don’t also state that the consciousnesses of physicists alone affect what they’re observing.

So what about the observer effect itself?

Idealism and Scientific Observation

Almost every time the word “observer” (or “observation”) is used in physics, some level of physical manipulation of the experimental setup is meant.

Take the following basic introduction to the observer effect:

“In physics, the observer effect is the disturbance of an observed system by the act of observation.”

The cat is let out of the bag when this account continues in this way:

“This is often the result of utilizing instruments that, by necessity, alter the state of what they measure in some manner.”

None of the above even hints at idealism or anything mystical.

To repeat. In physics, there is never any (as it were) pure act of observation.

Thus, all this isn’t just a question of a mind observing an experiment and/or thinking about it. That act of observation includes “utilizing instruments”, and the physical manipulations of the experimental apparatus.

[In idealism, how can any separation at all be made between consciousness and an experiment? See note 2 on Bernardo Kastrup’s position.]

All this means that the word “observation” can be very misleading.

There are indeed conscious observations (carried out by persons) involved in experiments. However, there are physical elements to all these observations too.

Here again readers should note the words “the disturbance of an observed system”. Taken at face value at least, this clearly has nothing to do with (Carl Jung’s) “acausality”, “consciousness affecting reality”, mysticism, etc. It’s to do with the physical disturbances of an experimental setup (or physical arrangement) by the experimenters and their instruments.

Indeed, physicists also encounter the problem of making a separation between the behavior of a system, and that system’s interaction with measuring instruments and human experimenters. And that, in turn, leads to the problem of knowing what a quantum state is in the first place.

More specifically, in any double-slit experiment, it’s fairly uncontroversial to state that the observation of quantum phenomena by an instrument (or detector) can (or will) change the measured results.

To repeat. Here it’s said that the an instrument or electronic detector changes the results of the experiment. The very fact that we’re talking about an instrument shows that this isn’t only about consciousness, or even only about (purely mental) observations.

However, it’s worth mentioning the idea that the quantum realm is often deemed to be “weird” regardless of measurements, experiments and conscious observations.

An Heisenbergian Interlude: Intrinsic Weirdness

The philosopher and historian of science Robert P. Crease (quoted at the beginning) writes:

“The strangeness of the uncertainty principle is not due to the measurement process disturbing the object measured, which would be a feature of any Newtonian theory involving exchange of particles. Nor is it due to the presence of statistics. Rather, the strangeness of quantum mechanics is that quantum formulations are not ‘about’ a real or ideal object in the conventional sense.”

This position doesn’t help the mystical or idealist position either.

For a start, this essentially Heisenbergian passage doesn’t even mention “consciousness” or “the observer”. Instead, it can be taken to advance the position that the quantum realm is (as it were) intrinsically weird. That is, it is weird regardless of consciousness or the minds of physicists. Thus, this is hard position to directly (or even indirectly) connect to either idealism or to mysticism.

Despite all that, a double-slit experiment’s results have indeed been interpreted (with a stress on the word “interpreted”) as telling us that “consciousness can affect reality”.

Consciousness, Making a Mark and Observation

Many physicists are keen to stress that an “observer” needn’t be a conscious being — it simply needs to be a scientific instrument of some kind. Of course, minds need to read (or interpret) the instrument’s readings or “marks”. However, that alone hardly seems like a strong argument for idealism and/or for mysticism.

In any case, a mark is made before it is (further) registered by (the consciousness of) a physicist. In addition, the, say, “clicks of a detector” can only be noted by a conscious experimental physicist.

So it still seems obvious that a physicist (or consciousness) would be required to make sense of, say, a thermometer’s registration.

Erwin Schrödinger (who’s often pressganged into the idealist and mystical school) conveniently discussed both measurement and consciousness.

For example, in Schrödinger’s published lectures Mind and Matter (1956/58), he argued that

“there is a difference between measuring instruments and human observation: a thermometer’s registration cannot be considered an act of observation, as it contains no meaning in itself. Thus, consciousness is needed to make physical reality meaningful”.

So even if Schrödinger was influenced by mystical literature (though not when it came to his actual theories in physics), nothing in the passage above is (or need be) necessarily tied to anything mystical or idealist — not even his introduction of the word “consciousness”. In other words, the logical or philosophical point being made above is entirely free of any mystical and/or idealist connotations.

In any case, the thermometer still registered something regardless of any “consciousness” that later (as it were) made sense of that registration. More precisely, the thermometer must have gone through a certain physical process which ended up with a particular physical change. What’s more, all this must have happened before any mind gave it a (to use Schrödinger’s word again) “meaning”.

Sure, the thermostat’s state as it was before it was read or interpreted is of little (or even no) use to the physicist. However, it must still have had a physical state before it was read. [See note 3 on the Copenhagenist position on this matter.] In other words, the thermostat must have been in state x even before it was read or interpreted, and it was still in that state when it was read or interpreted.

Notes

(1) The latter issue was first extensively discussed by Norwood Russell Hanson in his well-known paper ‘Seeing and Seeing As’, which was published in 1969. See here too.

(2) In terms of idealism (or at least a certain brand of idealism), it simply can’t be said consciousness affects reality. That’s because reality itself is already supposed to be “universal consciousness”. So, on an idealist reading, consciousness affecting reality would actually be an example of consciousness affecting consciousness.

Interestingly, the idealist Bernardo Kastrup makes this point against other people who also deem themselves to be idealists. Specifically, Kastrup argues against those who say that “the brain is a conduit of universal consciousness”. (The “filter theory” of the brain.) He corrects them by saying that the brain too is an “image” or “representation” of consciousness. In Kastrup’s own words:

“The idea that the brain does not generate consciousness, but instead limits and filters it down, seems to require dualism and contradict idealism. After all, if all reality exists in consciousness, how can the brain — which is a part of reality — filter down that which gives it its very existence? A water filter is not made of water; a coffee filter is not made of coffee; how can a consciousness filter be made of consciousness? It sounds like a self-referential contradiction.”

Thus, consciousness can’t be “a conduit” of consciousness.

3) It can be supposed that idealists and perhaps some anti-realists can ask the following question:

How do you know the both states of the thermometer — both before and after any registration or interpretation — fully coincide?

This is a question that’s hard to take seriously in physics. However, it does have at least some philosophical substance.

No comments:

Post a Comment