(i) Introduction

Many readers will have noticed the numerous social-media memes which have Albert Einstein’s words embedded within them. Relevantly, most of these memes aren’t actually about his scientific theories and views, or even about science itself. Instead, most of them are posted to defend the view that Einstein was religious, or spiritual, or a socialist, or this, or that, or the other. Other memes concentrate on Einstein's private life.

More particularly, the users of Facebook and social media generally might also have also noted how often spiritual idealists (see here) and New Agers quote a handful of passages from German and Austrian physicists which were mainly spoken (or written) in the first three decades of the 20th century. The relevant point is that these much-quoted scientists rarely made an effort to tie their non-scientific views to their actual physical (i.e., technical) theories. What’s more, these physicists hardy referred to “Eastern thought” and spiritual stuff in the first place. Hence, the very-few passages which spiritual commentators, New Agers, etc. quote and embed in their memes.

Erwin Schrödinger is a good example of all this.

He actually went out of his way to disconnect his interest in (loosely called) Eastern religion from his actual technical physics. [See note 1.]

New Agers, on the other hand, do the opposite of this.

Such people go out of their way to connect — specifically — quantum physics to their prior spiritual beliefs.

So are all these (as it’s put in philosophy) contexts of discovery important to the scientific theories of particular scientists?

Indeed, are they contexts of discovery at all?

Sokal’s Sex Life and Kripke’s Schooldays

In extreme terms, it doesn’t matter if the scientist discussed (or memed) was also, say, a serial killer, a Nazi, a neoliberal, a narcissist, etc. In Einstein’s particular case, it doesn’t matter that he was (according to Metro newspaper) a “misogynist” and “neanderthal”.

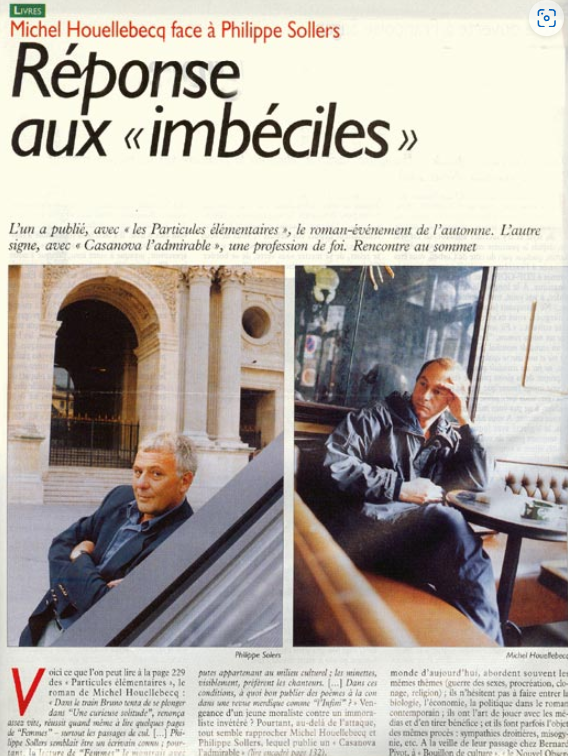

Yet, to take just one example, the French critic and writer Philippe Sollers was very interested in contexts of discovery. Or at least he was interested in in the sex life and personal psychology of a mathematician and physicist.

So now take American mathematician and physicist Alan Sokal and the physicist and philosopher Jean Bricmont and their words (from the book Intellectual Impostures) on Philippe Sollers’ words (see image above) on… well, Sokal and Bricmont themselves:

“[] Philippe Sollers asserts [] that our private lives ‘merit investigation’: ‘What do they like? What paintings do they have on their walls? What are their wives like? How are those beautiful abstract statements translated in their daily and sexual lives?’

“Well! Let’s concede once and for all that we are arrogant, mediocre, sexually frustrated scientists, ignorant in philosophy and enslaved by a scientistic ideology (neoconservative or hard-line Marxist, take your pick).”

In any case, how did Alan Sokal react to Philippe Sollers’ words?

In the following way:

“But please tell us what this implies concerning the validity or invalidity of our arguments."

All that said, popular-science writers often become very fixated on biographical detail. Perhaps they do so for two related — as well as obvious - reasons:

(1) To popularise science and scientists

(2) To help sell their books.

Let’s now take a rather less sexy context of discovery.

The American philosopher and logician Saul Kripke was once honest enough to admit (in this video) that his initial interest in Ludwig Wittgenstein was solely down to who taught him at university when he was a student. (He mentions “three faculty members” particularly.) Of course, alongside the fact that his teachers had an interest in Wittgenstein (specifically the “late Wittgenstein” of the Philosophical Investigations) would have been the fact that Kripke actually developed an independent interest in what Wittgenstein wrote. Having said that, Kripke also confesses that he didn’t at first see the importance of Wittgenstein or his Philosophical Investigations. Indeed, he didn’t “develop [his] own take on what [Wittgenstein] was doing until 1962 and 1963”…

Then again, Kripke was still only 22 in 1962…

But who cares about all this biographical detail!

Well, a lot of people do.

Indeed, there’s nothing wrong with that.

The question is what relevance does it have to Kripke’s actual philosophical ideas in, say, logic, metaphysics, philosophy of mind, etc?

The context of Kripke’s discovery of Wittgenstein, in this case, will have no interest at all to those strict philosophers who’re solely interested in the context of justifying Kripke’s analysis of Wittgenstein.

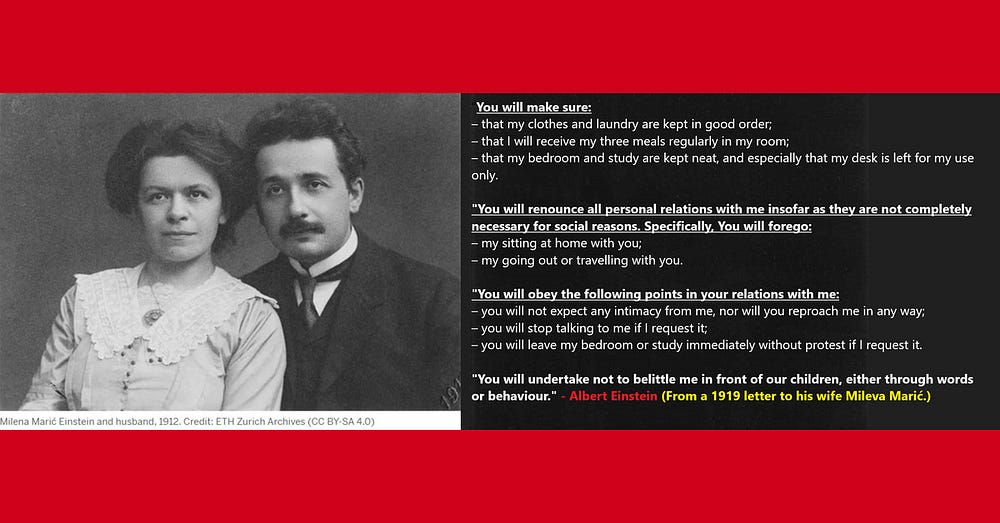

Thus, if biography and context are really so important when it comes to Sokal’s arguments (or to the scientific theories of scientists), then take the following letter (see here) which Einstein wrote to his wife in 1919? —

“You will make sure:

– that my clothes and laundry are kept in good order;

– that I will receive my three meals regularly in my room;

– that my bedroom and study are kept neat, and especially that my desk is left for my use only.

“You will renounce all personal relations with me insofar as they are not completely necessary for social reasons. Specifically, You will forego:

– my sitting at home with you;

– my going out or travelling with you.

“You will obey the following points in your relations with me:

– you will not expect any intimacy from me, nor will you reproach me in any way;

– you will stop talking to me if I request it;

– you will leave my bedroom or study immediately without protest if I request it.

“You will undertake not to belittle me in front of our children, either through words or behaviour.”

Have these words ever appeared in any social-media memes?

That said, Einstein’s letter to his wife (of the time) has indeed been tackled by journalists, and by some science writers too.

The point here is that if contexts of discovery can be used in positive ways, then they can be used in negative ways too.

More relevantly, if positive contexts of discovery can be tied to actual scientific theories and ideas, then so too can negative ones.

So can we pick and choose contexts of discovery according to taste?

Now let’s just pretend that Einstein was a serial killer, or a neanderthal, or a misogynist — or perhaps all three at once.

How would, say, the historian of science and philosopher Robert P. Crease deal with these possibilities?

Robert P. Crease on the Envy, Rivalry and Anger of Scientists

Robert Crease isn’t just interested in contexts of discovery: he actually ties the scientific theories of physicists to their (as it were) extra-curricular activities and beliefs…

Or at least he seems to!

Crease believes such that such scientific theories actually embody aspects of the (as it were) biographical detail of the scientists who created them.

So take this passage from Crease:

“[I]n Einstein [] we can see glimpses of what lies beyond the standard model: an account of science in which character and personal feeling are not marginal to the scientific process, not a prelude to a person’s scientific labours, but what sustains them and carried them forward.”

Of course it can still be asked if Crease is actually arguing that all this “character and personal feeling” is somehow embodied in scientists’ scientific theories.

So if it is, then how is it so?

What’s more, what is Crease actually pitting himself against?

Crease is pitting himself against what he (ironically) calls “the standard model [of] [m]ost histories of science”. Crease writes:

“It emphasises the collective and impersonal dimension, and downplays the experiences of specific individuals. The principle structural ingredients are discoveries, instruments, measurements, and theories.”

Is this true?

Do historians really “downplay[] the experiences of specific individuals”?

Not in the cases I’ve read.

Indeed, if we move away from historians of science, popular-science writers certainly don’t!

So perhaps that’s the very distinction Crease is making: the distinction between historians of science and popular-science writers. (Crease has himself written such a popular-science book — the one these quotes come from.)

Moreover, even if what Crease says about historians of science is true, then what are we to make of all these experiences of specific individuals from a scientific point of view?

Of course, much — very much ! — has been made of them from all sorts of other points of view.

However, what relevance do the specific experiences of specific scientists have to their specific scientific theories and ideas?

In more detail, Crease also tells us that

“[e]nvy, rivalry, anger, disbelief, conviction, stress, hope, despair, dejection — all can be found in the documents”.

Has any historian of science argued that scientists don’t experience envy, rivalry, anger, disbelief, conviction, stress, hope, despair, rejection? Has any scientist himself ever argued this about his fellow scientists?

Like the physicist and popular-science writer Paul Davies (to be discussed in a moment), Robert Crease believes that all of this experience becomes embodied in the actual scientific theories of scientists…

Or at least I think that’s what he believes.

As already stated, it’s hard to see what Crease is getting at otherwise.

In any case, Paul Davies certainly does believe this.

Paul Davies on Newton’s Religious Contexts of Discovery

The popular-science writer and physicist Paul Davies goes much further too.

For example, Davies is keen to stress Isaac Newton’s religious beliefs, and how they influenced (or even determined) his actual physics. (See Davies’s ‘Taking Science on Faith’ for the New York Times.)

Thus, if this is true (in this case at least), then the context of discovery can’t be separated from from the context of justification at all. That’s because Davies is making a direct link between Newton’s scientific theories and his religious beliefs.

On the other hand, if that link between contexts of discovery and actual scientific theories isn’t there, then (at its crudest) it wouldn’t make the slightest bit of difference to Newton’s scientific theories and ideas whether he too was a serial killer, or believed in pink goblins, or was a Christian fundamentalist, or that he stole all his ideas from Leibniz.

Of course, much has also been made of Newton’s (as it were) religious credentials by other people.

For example, spiritual-but-not-religious people and New-Agers have made much of Newton’s alchemy, Biblical prophesies, chronologies, fixation with numbers, interpretations of the Bible, and his takes on the philosopher’s stone and sacred geometry.

What’s more, their biographical and historical detail about Newton may well be largely correct!

Rupert Sheldrake Against the Distinction

Say that Einstein was a serial killer or a misogynist.

Many scientists (as it were) get around all this with the distinction they make between science itself and (flesh and blood) scientists.

Philosophers attempt a similar job with their own distinction between the context of discovery and the context of justification.

However, some critics of science (e.g., postmodernists, poststructuralists, religious and spiritual people, some Marxists, psychoanalysts, Jungians, etc.) have argued that this distinction is a phoney. And it’s phoney largely because they see it as an idealisation and a simplification.

Take the related case of the scientist, writer and parapsychology researcher Rupert Sheldrake.

It can be assumed that Sheldrake will be aware of this context-of-discovery/context-of-justification distinction. However, it can also be assumed that he doesn’t really buy it — at least not unquestioningly. (I doubt that anyone accepts it unquestioningly. I don’t.)

Take the following passage:

“To this day, scientists pretend that they are rather like disembodied minds. Unlike other human activities, science is supposed to be uniquely objective. Scientific papers are conventionally written in an impersonal style, seemingly devoid of emotions. Conclusions are meant to follow from facts by a logical process of reasoning, such as that which might be followed by a computer, if machines with sufficient artificial intelligence could ever be constructed. Nobody is ever seen doing anything, methods are followed, phenomena observed, and measurements are made, preferably with instruments. Everything is reported in the passive voice. Even schoolchildren learn this style, and practise it in their laboratory notebooks: ‘a test tube was taken…’

“All research scientists know that this process is artificial; they are not disembodied minds, uninfluenced by emotion.”

So what if scientists did believe that they have “disembodied minds”? Where would that lead us? Would it impact on the attitude we have to their actual scientific theories, and to science generally?

Moreover, do any of Sheldrake’s psychological analyses of scientists (even if genuinely insightful) matter? (Readers may now ask: Matter to whom? Matter in which respects?)

In any case, isn’t this simply Sheldrake’s biased interpretation of what scientists believe? Indeed, even if (most? many? some?) scientists do believe that they have a monopoly on what people call “the objective facts”, then that still wouldn’t entail a commitment to believing that their minds need to be disembodied in order to access those objective facts.

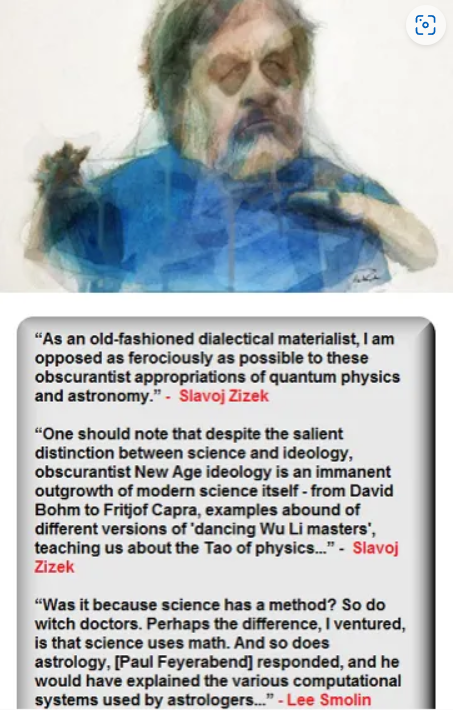

The philosopher Zizek (who uses the words “objective truth-values”) is also against the distinction. However, he never actually uses the technical terms “context of discovery” and “context of justification”.

Slavoj Žižek Against the Distinction

Firstly, Žižek tells us that the “standard distinction” is between

“the social or psychological conditions of a scientific invention and its objective truth-value”.

Žižek has a problem with this division (or distinction).

He continues:

“The least one can say about it is that the very distinction between the (empirical, contingent sociopsychological) genesis of a certain scientific formation and its objective truth-value, independent of the conditions of this genesis, already presupposes a set of distinctions (between genesis and truth-value, etc.) which are by no means self-evident.”

Let’s firstly comment on certain terms which Žižek uses, and which are questionable.

Take his words “objective truth-value”.

Surely one can make a distinction between the context of discovery (or Žižek’s “genesis”) and the context of justification, and still not have a strong (or even any) commitment to objective truth-values.

For one, what does “objective” even mean in this context?

The words “scientific invention” also (to use Žižek’s own words) “presuppose[] a set of distinctions” which Žižek himself is making. In this case, he appears to believe that scientific theories (or even experimental findings) are little (or even nothing) more than inventions.

Of course, “invention” is a loaded term. Nonetheless, Žižek is on fairly strong ground here because some quantum theorists (who’re also physicists) stress this.

Take “quantum Bayesianism” (Qbism) and the position of Christopher Fuchs.

Fuchs believes that “quantum states represent observers’ personal information, expectations and degrees of belief”. More relevantly, Fuchs believes that this

“allows one to see all quantum measurements events as little ‘moments of creation’, rather than as revealing anything pre-existent”.

Now what could be more (as it were) constructionist, and, more relevantly, biographical than stressing (scientific) “moments of creation”?

Note:

(1) See Walter Moore’s excellent biography: Schrödinger: Life and Thought. Moore goes into much detail on Schrödinger’s interest in Schopenhauer, Vedanta, etc.

No comments:

Post a Comment