Many 20th century philosophers set themselves the task of defining (or redefining) the words “true” and “truth”. They wanted to see how these words were actually used in their many and varied contexts. This meant that such philosophers didn’t want to embark on the ancient — and perhaps fruitless — philosophical journey of discovering “the nature of truth” — as if truth were a pre-existing entity (or property) which has a determinate and circumscribed nature regardless of how individuals, groups and societies use the words “truth” and “true”…

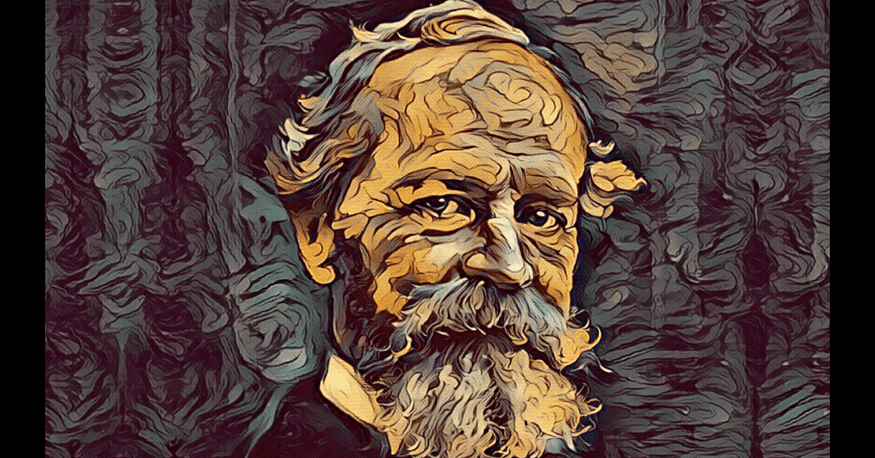

However, let’s go back in time to the 19th century here and start with the American philosopher and psychologist William James (1842–1910).

The American philosopher Richard Rorty (who died in 2007) put James’s position in the following way:

“If we have the notion of ‘justified’, [then] we don’t need that of ‘truth’.”

Rorty went on to claim that James believed that the word

“‘[t]rue’ must mean something like ‘justifiable’”.

On this reading, then, it seems that we could (or should) literally erase the word “true” from our language, and simply substitute it with the word “justifiable”. Yet if “true” actually means “justifiable”, then there’s simply no need to erase the word “true” at all.

What’s more, as a pragmatist, James wouldn’t have deemed the erasure of the word “true” as a viable or sensible option. In other words, the everyday uses of the words “true” and “truth” have pragmatic utility. However, just don’t reify (or Platonise) them.

William James wasn’t really setting up a literal identity between truth and justification. In other words, it didn’t make sense to view these terms in the abstract.

Let’s now spell out James’s (possible) position:

A true statement is a statement which has been justified (or whose utterance is justifiable).

As can be seen, the statement above is about other statements: it’s not a statement about the physical or metaphysical world.

So what about the the thing (or the property) truth?

Well, we can bite the bullet and argue that truth is indeed an abstract property. It’s only a property of certain statements… However, even this isn’t really the case because the predicate “is true” (or the word “true”) is applied to certain statements — it’s not an actual property of those statements themselves. (This is vaguely equivalent to putting a dress on a mannequin: the mannequin and the particular dress aren’t the same thing.) Thus, outside the context of those statements we deem to be true (or which have been justified), perhaps there is no property that is truth.

Despite all the above, Rorty still believed that James was in “error”. He continued:

“The error is to assume that ‘true’ needs a definition [ ].”

Rorty wasn’t taking truth to be a thing or even a property. Instead, “truth” (or “true”) is a word which human beings use about certain statements. So beyond what human beings say about these particular statements, there is no thing (or property) which is truth.

More precisely, when we say that statement S “is true”, this is simply an affirmation of that statement. That said, we may still believe (to get back to James’s position) that statement S is justified (or justifiable), and therefore we’ll go straight ahead and affirm it…

Of course, we needn’t necessarily be committed to James’s particular stress on justification, let alone be committed to believing that the word “true” can be substituted with the word “justified”.

Rorty then went on to claim that idealists too made a similar (or the same) error about the word “truth” (or the property truth). He wrote:

“This was a form of the idealist error of inferring from

‘We can make no sense of the notion of truth as correspondence’

to

‘Truth must consist in ideal coherence.’ [ ].”

So the notion of “truth as correspondence” (which idealists had a problem with) fails because, again, if there’s no thing (or property) truth in the first place, then truth can’t be “ideal coherence” either. [There are, surprisingly, many other problems with the intuitively plausible truth-as-correspondence idea. See here.]

So there are two things which should be noted here:

(1) It is certain statements (i.e., not facts, properties, things, states of affair, etc.) that are true. (Truth isn’t a thing or a property separate from certain statements.)

(2) By which criteria do we decide that statements are true — even if we accept that truth is not a thing or a property?

No comments:

Post a Comment