The following passage offers us a short account of the Liar Paradox:

“[T]he classical liar paradox [] is the statement of a liar that they are lying: for instance, declaring that ‘I am lying’. If the liar is indeed lying, then the liar is telling the truth, which means the liar just lied. In ‘this sentence is a lie’ the paradox is strengthened in order to make it amenable to more rigorous logical analysis. [] Trying to assign to this statement, the strengthened liar, a classical binary truth value leads to a contradiction.

“If ‘this sentence is false’ is true, then it is false, but the sentence states that it is false, and if it is false, then it must be true, and so on.”

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once confronted this well-known paradox. In a discussion with Alan Turing, he said:

“Think of the case of the Liar: It is very queer in a way that this should have puzzled anyone — much more extraordinary than you might think. Because the thing works like this: if a man says ‘I am lying’ we say that it follows that he is not lying, from which it follows that he is lying and so on.”

Wittgenstein continued:

“Well, so what? You can go on like that until you are black in the face. Why not? It doesn’t matter. [I]t is just a useless language-game, and why should anyone be excited?”

There is a paradox (or contradiction) here… but so what!

In broader terms, Wittgenstein stressed two things:

1) The strong distinction which must be made between accepting contradictions within mathematics (actually, metamathematics), and accepting contradictions outside mathematics.

2) The supposed applications and consequences of these mathematical contradictions and paradoxes outside mathematics. [See note 1.]

So at least some people should “be excited” by the Liar Paradox — logicians and metamathematicians...

As for 1), Wittgenstein said (as quoted by Andrew Hodges):

“Why are people afraid of contradictions? It is easy to understand why they should be afraid of contradictions in orders, descriptions, etc. outside mathematics. The question is: Why should they be afraid of contradictions inside mathematics?”

Thus, Wittgenstein can be read as not actually questioning the logical validity or status of these paradoxes. Instead, he was making a purely philosophical point about their supposed — and many — applications and consequences outside of metamathematics. [See note 1 again.]

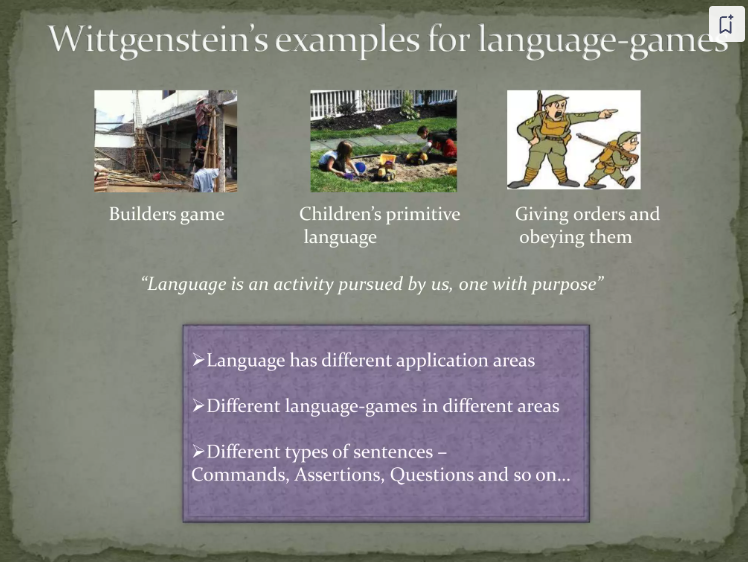

But what about Wittgenstein’s use of the term “language-game”?

On the Liar Paradox as a Language Game

At first glance, Wittgenstein was perfectly correct to use the philosophical term (his own) “language-game” to refer to the Liar Paradox (as well as to refer to many of the other paradoxes thrown up in what’s often called the foundations of mathematics). More correctly, these paradoxes were seen to arise within various language games.

To add to Wittgenstein himself. The Liar Paradox is internal to a language game which allows a very specific kind of self-reference…

But — again — why use the term “language game”?

Well, in which other language (or language game) would you ever find the statement, “This sentence is false”? (Even it’s supposed everyday translation — “I am a liar” — seems somewhat contrived.)

Thus, these kinds of sentence simply don’t belong to everyday languages at all. Thus, they must all belong to specific technical language games. (As do, for example, Gödel sentences.) [See note 2.]

So Kurt Gödel (for one) didn’t have any problems at all with self-reference. Indeed, he once wrote the following:

“Contrary to appearances, such a proposition involves no faulty circularity, for it only asserts that a certain well-defined formula [] is unprovable. Only subsequently (and so to speak by chance) does it turn out that this formula is precisely the one by which the proposition itself was expressed.”

On the surface, Wittgenstein would have had no problems with the impeccable logic of that passage from Gödel.

However, he might have argued that it’s not a question of what Gödel called “faulty circularity”. Perhaps, instead, it’s also about whether anything at all can be affixed to (or said of ) such sentences as “This statement is not provable” (or even “This statement”). More specifically, if these statements are semantically (as well as scientifically, empirically, and even metaphysically) empty, then perhaps we really don’t need to worry about even the possibility of Gödel’s faulty circularity.

Of course, logicians can — and do — use weirder statements such as “Bricks have a sense of humour” or “The number 2 is blue” logically. That is, they can assign a truth value to such statements, and then treat them as pure syntactic strings (from which they can derive further statements and conclusions). Similarly, we can programme the words “The number 2 is blue” into a computer, and then that computer can grind out further statements (i.e., if it’s programmed in the right way).

To repeat. Wittgenstein didn’t argue that such cases of self-reference were bogus, or even that they have no value. Instead, he simply saw them as being part of particular (technical) language games. And from that, many things followed.

The Liar Paradox Was Created, Not Found

Wittgenstein’s position can be summed up by saying that the Liar Paradox (or the Liar Language Game) doesn’t display (or uncover) a contradiction or paradox — it actually creates one.

So Wittgenstein was stressing the artificiality of the Liar paradox.

However, that artificiality doesn’t automatically mean that the Liar Paradox has nothing to offer us. In other words, the word “artificiality” needn’t be used negatively. It may simply a reference to something which is artificial…

As it is, though, Wittgenstein did mean it in a (fairly) negative way. After all, he did say that the Liar Paradox “is just a useless language-game”.

Alan Turing, on the other hand, seemed to be interested in the Liar Paradox for purely logical and intellectual reasons. He replied to Wittgenstein in the following manner:

“What puzzles one is that one usually uses a contradiction as a criterion for having done something wrong. But in this case one cannot find anything done wrong.”

To repeat. Wittgenstein wasn’t denying that there is a contradiction here. Instead, he was simply asking questions — and making points — about the Liar and other paradoxes.

In basic terms, then, Turing was arguing that, unlike many other cases of contradiction, the Lair Paradox doesn’t simply uncover a contradiction: it makes it the case that x and not-x must both be accepted. That is, when the (Cretan) liar utters “I am lying”, and it leads to it being interpreted as making him both a liar and not a liar (i.e., at one and the same time), then “in this case one cannot find anything done wrong”.

One can almost guess Wittgenstein’s reply to Turing. He said:

“Yes — and more: nothing has been done wrong [].”

So when it comes to the Liar Paradox, “one cannot find anything done wrong”!

In other words, nothing has been done wrong in that particular language game. However, outside that particular language game, much has been done wrong. Or, at the very least, much of this language game is semantically — and otherwise — very weird.

Finally. Wittgenstein’s argument is that the Liar Paradox does indeed lead to a bizarre conclusion. However, that’s because — in a strong sense — it was designed to do so. In other words, the Paradox is part of a language game which was specifically created to bring about a contradiction. What’s more, because it’s a self-enclosed and artificial language game, Wittgenstein ended by asking the following question:

Where will the harm come from allowing such a contradiction or paradox?

Notes

(1) These consequences — if not always applications — of the Liar and other paradoxes usually include stuff about consciousness, God, human intuition, the universe, human uniqueness, religion, arguments against artificial intelligence, meaning, purpose, etc.

(2) Of course, everyday language does allow other kinds of self-reference which don’t generate contradictions or paradoxes, such as merely referring to oneself when one says “I am happy”.

No comments:

Post a Comment