The point is not to interpret the world, but to sell more books.

- A paraphrase (well, rewriting) of a well-known passage from Karl Marx.

i) Introduction

ii) Sexy Philosophy

iii) Markus Gabriel: The World Does Not Exist

iv) Graham Priest: Setting Contradictions Together

v) Rudy Rucker: Rocks Have Minds

vi) Donald Hoffman: The Case Against Reality

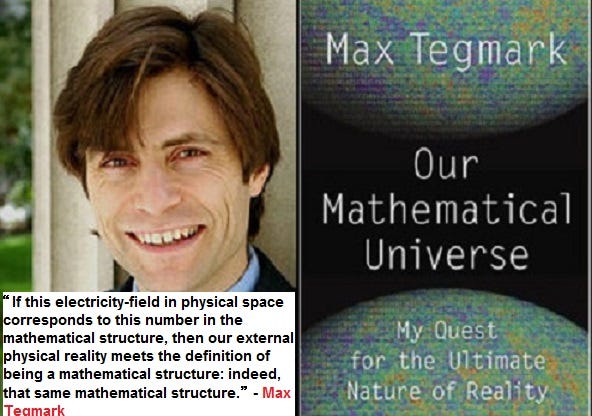

vii) Max Tegmark: The World is Mathematics

**********************************

Let’s begin with just a few words on the title of this piece.

The German philosopher Markus Gabriel (1980-) had a book called Why the World Does Not Exist published in 2015. And, despite appearances, the words “the world does not exist” certainly aren’t as radical, extreme and/or sexy as they may first appear.

Gabriel’s position isn’t that there are no people, chairs, cats, etc. around us. It isn’t even that there are no elves, gods, numbers, etc. And Gabriel’s position certainly isn’t some new-fangled type of solipsism either. Instead, the phrase “the world does not exist” is essentially Gabriel’s reaction to past philosophical uses of the word “world”!

Of course the words “the world does not exist” may not be meant to be taken literally or in any everyday sense (that is, if there is such a sense). And then there’s the fact that Gabriel means something very specific by the word “world”. Having said all that, if these and other facts were made clear to most of Gabriel’s potential readers, then the words “the world does not exist” would no longer retain their sexiness and therefore saleability.

I’ll get back to Markus Gabriel later.

So, sure, partly because of the above, it can be happily acknowledged that this piece will include some ad hominems. Or, more charitably (to myself at least), this piece will include what may be called (amateur) sociological and psychological speculations. That said, such ad hominems and speculations may still be interesting, useful, relevant and even true. In other words, the (analytic) philosophers who blanch at all ad homs (if any ever do genuinely free themselves from this vice) need to advance arguments as to why such things are always irrelevant or pointless in each and every respect. Of course such philosophers may simply argue that “it’s not philosophy”, rather than take an absolute position on this.

I’m also willing to accept that I may be wrong about some of my choices and no doubt readers will choose their own targets when it comes to sexy (or saleable) philosophy. Indeed some of my own philosophical positions may be deemed — by other people — to be extreme, radical and/or sexy. For example, I’m fairly sympathetic to Ontic Structural Realism with its “every thing must go” motto. Yet even here those words in quotation marks are not what they seem. That is, they’re mainly —in some cases only — applicable to the things in the quantum realm. (That said, Ontic Structural Realism has indeed been applied to the “classical” world — or to classical things — too. It therefore bears a resemblance to the philosophical position relationism.)

In any case, I’d like to believe that I’m doing something similar to what the science writer Philip Ball (1962-) is doing when he writes about those who constantly sex-up quantum mechanics. (In that sense, Ball is a real party pooper.)

Take, for example, all the sexy memes of quantum mechanics: 1) That “quantum objects can be both waves and particles”. 2) That such objects “can be in more that one state at once: they can be both here and there”. 3) That quantum objects “can affect one another instantaneously over huge distances”. 4) That “you can’t measure anything without disturbing it”. (Thus making QM “unavoidably subjective”.) Finally: 5) That “everything that can possibly happen does happen”.

Now that really is a sexy bag of tricks.

So what does Philip Ball think about it? He concludes:

“Yet quantum mechanics says none of these things. In fact, quantum mechanics doesn’t say anything about ‘how things are’. It tells us what to expect when we conduct particular experiments. All of the claims above are nothing but interpretations laid on top of the theory.”

So let’s return to philosophy.

Sexy Philosophy

Philosophers really should write something that is extreme, radical and/or sexy. That way they’ll gain more readers and, perhaps, make more cash. And that’s why some of them do write things that are self-consciously extreme, radical and/or sexy. That effectively means that it doesn’t matter how shallow the positions of these philosophers are: if their philosophies are extreme, radical and/or sexy, then lots of (or at least more) people will buy their books.

So just to take three example. You’ve got panpsychism — which is very fashionable today. You’ve still got loads of stuff about zombies. And then dialethism: a position that happily accepts that contradictions — apparently — exist (or at least can exist) together.

(Zombies are of course very useful in terms of philosophical thought-experiments. However, that’s not their main appeal — even in philosophy.)

As hinted at in the introductory words about Marcus Gabriel, some of the positions tackled in this piece — and those elsewhere — aren’t as extreme, radical and/or sexy as they first appear. That is, once you tackle what’s actually being argued, then what some of these philosophers claim isn’t as outré as they’d like people (or their publishers) to think. And, when they actually are as radical, sexy and/or extreme as they appear, then they often don’t hold much philosophical water anyway. (In terms of this piece alone, the positions which aren’t as radical or sexy as they first appear are Markus Gabriel’s philosophy and Graham Priest’s dialetheism. And Rudy Rucker’s own brand of panpsychism doesn’t hold any philosophical water — but most certainly is sexy!)

Of course these sexy philosophers — and all philosophers — are human.

Many want to be famous. They want to sell as much of their product as possible. (Philosophers need to pay their mortgages, look after their families, buy another car, etc.) And if philosophical sexiness, radicalness and/or extremity sells better that “pedantic irrelevance”, etc, then such philosophers will sell such things. Thus, for example, there’s a Radical Philosophical Theory in the market place almost every day. And there’s even a New Theory of Consciousness on sale seemingly every week.

It must be also said here that perhaps my very own radical, sexy or extreme position is to point out the market-place mentality of such philosophers. And perhaps I want this piece to make me lots of money and make me famous too. (This is the classic self-referential problem with ad hominems and psychologising.) Yet even if that were the case, then what I write about these contrarian writers would still hold. It would simply now be the case that it may apply to myself too.

Finally, it must also be admitted that some of these sexy, radical and/or extreme philosophers have done much (technical) hard work. That is, even if they’re keen to use sexiness, extremity and/or radicality to sell their philosophical products, they may still have done much (technical) work in order to produce such a saleable product. And it may even be the case that these sceptical — or simply cynical — positions on sexy philosophy may not apply to all the philosophers and all the positions mentioned in this piece. That said, I’m very sure that they apply to at least some of them.

So now for a few examples.

Markus Gabriel: The World Does Not Exist

The philosopher Markus Gabriel once stated that “most contemporary metaphysicians are [sloppy] when it comes to characterizing their subject matter”. More specifically, he said that they used the words “the world” and “reality” in very imprecise ways. Such philosophers also use them “interchangeably and without further clarifications”.

In terms of Gabriel’s own position on the words “the world”, he writes:

“The idea that there is a big thing comprising absolutely everything is an illusion, albeit neither a natural one nor an inevitable feature of reason as such.”

Oddly, all the above makes Gabriel sound like a ordinary language philosopher from the 1940/50s. (Who knows, perhaps he wouldn’t deny this.) More specifically, Gabriel argues:

“In my view, those totality of words do not refer to anything which is capable of having the property of existence.”

So regardless of the intricacies of Gabriel’s philosophical position and whether it is true (or right) or false (or wrong), his problem is that the word “world” — as used by philosophers at least — is problematic. Sure, he also has a philosophical take on the world — yet it is the use of the word “world” that caused him to concoct the sexy phrase “the world does not exist”.

In more detail, Gabriel states:

“I call metametaphysical nihilism the view that there is no such thing as the world such that questions regarding its ultimate nature, essence, structure, composition, categorical outlines etc. are devoid of the intended conceptual content.”

So Gabriel appears to happily accept that there are things/objects, events, conditions, states, etc. in…well, the world — it’s just that there “is no such thing as the world”. In very basic terms, then, the word “world” is an abstract noun — at least as used by philosophers. Therefore it can’t help but be — almost by definition - philosophically problematic. (Perhaps we can step out of semantics and make the ontological point that the nature of the world itself is problematic.) This basically means that Gabriel has the same critical position on the words “the world” and “reality” as philosophers have traditionally had on words such as “truth”, “universal”, “mind”, “right”, “self”, etc. In fact many philosophers have indeed already scrutinised the words “the world” and “reality” too. (Gabriel admits his debt to Rudolf Carnap on this issue when he says, for example, that “existence is always relative to one of more fields of sense”.)

And it’s precisely because Gabriel has a critical position on the words “the world” that certain of his other philosophical positions follow on from that.

For example, Gabriel’s positions seem to owe much to modal realism — as well as to fictionalism. So, according to a Guardian article, Gabriel’s

“world is bigger than the universe, and includes not just humans but elves, fairies, Prime Minister Ed Miliband and unicorns on the far side of the moon — everything that exists, even if only in the imagination”.

In fact nearly all Gabriel’s positions have already been advanced by previous philosophers.

Sure; it’s not being said here that Gabriel’s positions are identical to his philosophical forbears. So, for example, I don’t know of any previous philosopher who used the precise phrase “the world does not exist”. Indeed Gabriel makes a strenuous effort to argue that, say, he’s not a fictionalist or an ontological pluralist. Yet it turns out that he is influenced by these positions and has certainly bounced off them. The fact that he has tweaked them a little to make sure that he’s not seen as a philosophical parasite may not amount to much when taking a view on his broader philosophy.

More specifically, the reason for Gabriel’s phrase “the world does not exist” can be traced back to Kant’s position that “existence is not a property”. And, indeed, Gabriel acknowledges this. Yet, again, Gabriel is also at pains to stress that his position isn’t identical to Kant’s. (Of course it isn’t!) In Gabriel’s own words:

“Yet, what is right about his view is that to exist is a property of a field or a domain and not an ordinary discriminatory property of objects we encounter within the domain. As I read him, Kant distinguished between questions concerning the existence of individuals (which he takes to be a function mapping individuals onto the field of possible experience) and questions concerning the world itself. The latter, metaphysical questions, for him, are famously unanswerable.”

There’s also a lot of anti-science stuff — or at least strong criticisms of physics — in Gabriel’s book. And that’s been done to death by numerous philosophers over the last 100 years or longer too. Thus views similar to Gabriel’s can also be found in Edmund Husserl, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Martin Heidegger, Paul Feyerabend, Thomas Nagel, etc. (Perhaps Gabriel wouldn’t deny his debt — and he does mention Heidegger on this subject.)

And, of course, all this — at least partly — ties in with the words “the world doesn’t exist”. That is, Gabriel argues that physics doesn’t supply us with the only (to use Gabriel’s technical term) “field of sense”. In fact he believes that there are infinite fields of sense. Thus, because physics can never know “the infinite”, then it must never speak of “the world” or even of “reality”.

Now for Graham Priest’s dialetheism in which “contradictions are embraced”.

Graham Priest: Setting Contradictions Together

Does Graham Priest (1948-) genuinely “set contradictories together” in the world? (Of course Markus Gabriel wouldn’t be very happy with the words “the world”.) For example, can a specific cat both have and not have a tail? Or is this example too crude or simplistic? Though if it is, then what, exactly, is Priest’s position? Indeed are even the “paradoxes” of quantum mechanics what they seem? (Priest sometimes uses quantum mechanics as grist to his mill.)

So is Graham Priest’s dialetheism about the world (i.e., an ontological position) or is it about what we can — or even should — say about the world?

Clearly, if it’s about the world, then it’s far sexier than merely being about our epistemic or logical take on the world.

These questions are asked because there’s virtually nothing in Priest’s work where he explicitly states that contradictions exist in the world. In basic terms, it’s all about how “contradictions can be embraced” in logic, epistemology and the philosophy of science (as well as in science itself).

It may seem, then, that Professor Bryson Brown is accepting my view in the following. Or, at the least, firstly he writes:

“Of course a defender of [David] Lewis’s position might argue that we never really accept inconsistent premises.”

However, Brown then concludes:

“But this seems untenable. After all, we are finite thinkers who do not always see the consequences of everything we accept. In particular, as we saw above, we may well not know our premises are inconsistent.”

Yet even Brown’s conclusion doesn’t commit anyone to inconsistencies or contradictions actually existing (or having being) in the world. His words too are a question of what we know — or rather, in this case, what we don’t know. That is, because we

“do not always see the consequences of everything we accept [and] may well not know our premises are inconsistent”

then that has nothing to do with the world itself. It’s to do with human beings and our cognitive limitations.

Of course, if there are abstract mathematical and logical worlds, then these paradoxes, contradictions and inconsistencies may exist (or have being) there instead.

Yet Priest does argue that dialetheism isn’t (purely) a formal logic. He states that it’s “a thesis about truth”. (At the least, truth as it’s thrown up primarily by various paradoxes in set theory and elsewhere.)

Bryson Brown (in his paper ‘On Paraconsistency’) again stresses the importance of inconsistency for dialetheism and also states that dialetheists are “radical paraconsistentists”. He writes:

“[Dialetheists] hold that the world is inconsistent, and aim at a general logic that goes beyond all the consistency constraints of classical logic.”

Yet deriving the notion of an inconsistent world (or a world which contains contradictions) from our psychological and/or epistemic limitations (as well as from accepted notions in the philosophy of science and mathematics) is problematic. In other words, the epistemological position that we have inconsistent (or even contradictory) positions (or systems) can’t also be applied to the world itself.

Another way to put this is in terms of set-theoretic paradoxes, as also mentioned by Bryson Brown.

Brown says that “the dialetheists take paradoxes such as the liar and the paradoxes of naïve set theory at face value”. That is, it may be the case that dialetheists choose — for logical and/or philosophical reasons — to accept paradoxes even though they also believe that, ultimately, they aren’t true of the actual world. (As already stated, if there are abstract mathematical and logical worlds, then these paradoxes, contradictions and inconsistencies may well exist there.) That said, Brown continues by saying that dialetheists “view these paradoxes as proofs that certain inconsistencies are true”…

These inconsistencies are true of what?

True only of the paradoxes (as it were) in themselves?

Or true of the (physical) world itself?

This stress on the world may betray a naïve, crude and, perhaps, an old-fashioned view of logic. Nonetheless, Priest himself does mention “reality” on a few occasions. When discussing the virtue of simplicity, for example, he asks the following question:

“If there is some reason for supposing that reality is, quite generally, very consistent — say some sort of transcendental argument — then inconsistency is clearly a negative criterion. If not, then perhaps not.”

Here is more of Priest’s own position on consistency. He writes:

“[W]e all, from time to time, discover that our views are, unwittingly, inconsistent.”

And, when discussing the virtue of simplicity, Priest also asks the following question:

“If there is some reason for supposing that reality is, quite generally, very consistent — say some sort of transcendental argument — then inconsistency is clearly a negative criterion. If not, then perhaps not.”

As dialethic logicians have stated, we can accept inconsistent scientific theories if they still prove to be useful and have predictive consequences. In fact scientists (especially physicists) have been fine with this situation for a long time. Priest puts it this way:

“Inconsistent theories may have physical importance too. An inconsistent theory, if the inconsistencies are quarantined, may yet have accurate empirical consequences in some domain. That is, its predictions in some observable realm may be highly accurate. If one is an instrumentalist, one needs no other justification for using the theory.”

Bryson Brown also says that

“our best theory of the structure of space-time, Einstein’s general theory of relativity, is inconsistent with our quantum-mechanical view of microphysics”.

Brown also mentions the Danish quantum physicist Niels Bohr within this context.

Did Bohr believe that there were inconsistencies — let alone contradictions — actually in the world? Philosophers have disagreed on this. However, it can be argued that Bohr might have found it difficult to grasp what an inconsistent world (or any aspect of the world) would — or could — be like. This is at least the case when it comes to worldly contradictions. That is, it is hard to see how A & not-A can be the case at one and the same time.

This means that we need to decide if embracing theoretical inconsistencies (in science, logic, etc.) also means embracing worldly contradictions.

Bryson Brown also acknowledge the fact that, in general, we “accept non-trivial but inconsistent obligations and/or beliefs”. Here again this is an epistemic and moral matter. More explicitly, it isn’t the case that we believe that “Cats have tails” and “Cats don’t have tails” at one and the same time. No one believes that an individual cat both has a tail and doesn’t have a tail. So, in that case, A works in one context; and ¬A works in another context. In other words, “cats have tails” (which, grammatically, doesn’t entail “All cats have tails”) is about cats in the plural; whereas any statement about an individual cat won’t be about all cats. Yet an individual cat both having and not having a tail means that the statements “Cats have tails” and “Cats don’t have tails” are both true. (This, admittedly, is also about cats in the plural.)

In Priest’s terms, this truth-value indeterminacy (though p’s being indeterminate is itself be seen as a truth value) results in a scientific theory (or logical system) being inconsistent. And that inconsistency is a result of the logician or scientist being unable (at least at a given point in time) to erase certain inconsistencies from his system or theory. (This is something that’s often been said about Bohr’s well-known model of the atom.)

As it is, it’s difficult to see how the world can be either inconsistent or consistent (or contradictory or contradiction-free). This position is similar — or parallel — to Baruch Spinoza’s philosophical point that the world can only… well, be. Thus:

“I would warn you that I do not attribute to nature either beauty or deformity, order or confusion. Only in relation to our imagination can things be called beautiful or ugly, well-ordered or confused.”

What we say about the world (whether in science, philosophy, mathematics, logic or everyday life) may well be consistent or inconsistent. However, the world itself can neither be consistent nor inconsistent. Thus, it seems to follow, that inconsistency is neither a “negative criterion” nor a positive criterion.

Yet if dialethism is about the world, then Priest (to use his own example — see here) could indeed be both in New York and not in New York at one and the same time! If it’s about what we can say, on the other hand, then it’s simply a logic that can helpfully capture and formulate such things as the inconsistencies in scientific theories. Alternatively, dialetheic logic can advance the pragmatic option of seeing two contradictory positions as true (or simply usable) — at least for the time being!

Thus nearly all Priest’s examples of dialetheic contradictions are really about human perceptions of — or attitudes towards — the world, not the world itself. They also concern inconsistencies in scientific and (another area mentioned by Priest himself) legal theories about the world. This makes dialetheism either a position in epistemology or one in the philosophy of science. So, if all that is the case, then surely dialetheism isn’t a “robust ontology” which happily embraces contradictions-in-the-world after all.

Of course Priest’s next move may be to question this possibly bogus distinction between the world and our statements about — and knowledge of — the world. Actually, he does question this distinction and he even uses the term “social constructionism” about his own position.

All in all, then, it can be said that Priest uses positions in epistemology and the philosophy of science as means to back up (or defend) his (seemingly) very-radical logical dialetheism.

Ruder Rucker’s panpsychism is very radical and sexy too.

Rudy Rucker: Rocks Have Minds

In his short essay, ‘Mind is a universally distributed quality’ (which can be found in the book What is Your Dangerous Idea?), Rudy Rucker (1946-) states that “[e]ach object has a mind”. That is, “[s]tars, hills, chairs, rocks, scraps of paper, flakes of skin, molecules” all have minds.

Rucker isn’t simply arguing that all these objects have “experiences” or embody what some philosophers call “phenomenal properties”. And he certainly isn’t arguing that they only embody “proto-experience” (as some philosophers have it). No; Rucker uses the word “mind”; as well as the words “experiences” and “sensations”.

So now it must be said that when (some) philosophers talk about “experience” (or “phenomenal properties”), they aren’t necessarily also talking about minds. Take the Australian philosopher David Chalmers (1966-) and his words on this subject in the following:

“[E]xperiences may fall well short of what we usually think of as having a mind… because protophenomenal properties may be even further away from the usual concept of ‘mind’…”

However, it can of course be argued that experiences and phenomenal properties must surely come (as it were) attached to minds. The problem is, if Rucker were to be clear about all this, then his positions would be far less sexy. And, as a consequence of that, he’d almost certainly sell less books.

Yet perhaps many of Rudy Rucker’s claims aren’t meant to be taken literally. Perhaps they’re meant to be taken poetically, metaphorically or even spiritually. Indeed we do have the oft-used phrase “there are many ways of knowing” — so perhaps Rucker’s way of knowing is different to my own way of knowing and also to yours. In addition, it’s of course the case that some people will be keen to point out (if not in these precise words) that one person’s absurd position is another person’s commonsensical position.

In any case, it can be argued that Rucker doesn’t do his fellow panpsychists (see panpsychism) any favours. Or, at the very least, he doesn’t do the more philosophically rigorous and less flamboyant panpsychists any favours.

In my view, then, “romantic factors”, spiritualism, sexiness and even politics constitute the primary appeal of panpsychism when it comes to most panpsychists and their followers. The hard analytical work — if it comes at all — may well arrive (as it were) after the fact . Well, that’s my own ad hominem anyway.

Now for Donald Hoffman.

Donald Hoffman: The Case Against Reality

From the many things which Professor Donald Hoffman himself has written on spirituality, mysticism and religion (as well as the time he has given to people like Deepak Chopra, etc.), it seems that there are many non-philosophical and non-scientific factors behind Hoffman’s philosophical and even scientific positions — or at least behind his conscious realism. And these non-philosophical areas must surely increase the sexiness of Hoffman’s overall positions.

Spirituality and Stuff

The words directly above, of course, aren’t a claim that Hoffman doesn’t provide arguments and scientific data for his speculative philosophy. Nonetheless, this context may help us understand what it is Hoffman is attempting to do.

The bottom line is that there’s much that Hoffman states which seems to be tailormade for those who have religious, spiritual and/or mystical (i.e., non-scientific and non-philosophical) views of what “reality” truly is.

For example, take these words from Hoffman:

“According to conscious realism, you are not just one conscious agent, but a complex heterarchy of interacting conscious agents, which can be called your instantiation...”

Clearly Hoffman is advancing some kind of “holistic” (for want of a more suitable word) vibe here.

It can be said that much of what Hoffman says is also closely connected to “mysticism”. That’s not my own word, Hoffman himself uses it a few times. (He does so usually in interviews and seminars, rather than in his academic papers.) Despite that, Hoffman does (at least at times) distance himself from such things. He does so primary by saying that his position

“give[s] a mathematically precise theory of conscious experiences, conscious agents, and their dynamics, and then make empirically testable predictions”.

Having said all that, the fact that New Agers, etc. are now gobbling up Hoffman’s words and theories doesn’t automatically make them false or unscientific. This would be an example of relying on guilt by association. However, it does give people grounds for varying degrees of suspicion or scepticism.

Hoffman’s rejoinder may be that he’s certainly not doing religion, spiritualism or mysticism because of the scientific nature of his theories. Yet it can still be argued that the very least Hoffman should say is that he’s not only doing religion, spiritualism or mysticism.

Now let’s ignore whether or not there are genuinely scientific aspects to Hoffman’s specific position of conscious realism (there obviously are!) and put forward the fact that Hoffman’s science is used to advance positions (at least in part) which already existed long before — and independently of — all science. (He concedes as much here.) That, of course, doesn’t mean that the two independent magisteria of science and religion/spirituality/mysticism can’t be squared. Indeed I believe that Hoffman himself is attempting to do precisely that.

Finally, the term “magisteria” has just been used. This is Stephen Jay Gould’s term and it has been quoted by Hoffman himself. However, it can be argued that since Hoffman is attempting to literally fuse (or unite) these two magisteria (i.e., science and religion), then that must surely go against what Gould himself had in mind. That is, Gould stressed the mutual independence of science and religion — not their unity.

In this video Hoffman even presents himself as offering a midway position between theism/deism and atheism. And, later in the same video, Hoffman also concedes that he’s “giving religious people something that will be positive to them”. (Here Hoffman argues that all the scientific cases against the existence of God fail.) Finally, in this interview Hoffman says that the relationship between science and spirituality is “very deep”. More specifically, Hoffman states that

“many of the spiritual traditions have been telling us for centuries, even millennia, that spacetime is not fundamental but there’s a deeper reality outside of spacetime”.

Of course Hoffman will be keen to stress than none of these positions make him either a religious person or a theist/deist. So does Hoffman have his cake and eat it too?

In any case, the sexiest part of Hoffman’s overall position is his Zero Reality Theorem. That is, the thesis that we know or experience zero of reality.

Now that’s a very sexy, radical and extreme position.

The Zero Reality Theorem

Hoffman also calls this position The Fitness Beats Truth Theorem (the FBT Theorem). And that usage needs to be quickly commented upon.

There’s much more than mathematics to Hoffman’s various theorems (actually, theories): there’s also the philosophical speculations and the (physical) science.

Hoffman makes another mistake when he states the following:

“It’s very clear. If our senses evolved and were shaped by natural selection, the probability that we see reality as it is is zero.”

The final clause

“the probability that we see reality as it is is zero”

doesn’t follow from the first clause:

“If our senses evolved and were shaped by natural selection…”

That is, the final clause doesn’t follow unless one already accepts Hoffman’s various philosophical assumptions and arguments.

For a start, not seeing reality completely as it is isn’t the same thing as seeing “zero” (Hoffman’s word) of reality. Evolution might have designed us to see only limited aspects of reality. And that’s a very-old argument.

Many philosophers, for example, have argued that a (as it were) “Kantian manifold” couldn’t possibly be registered by a human brain or by human consciousness. And that’s because there’s simply too much information or data to take in. However, that doesn’t mean that we have zero knowledge of reality or the world. That is, we can’t quickly move from our not getting reality in toto to not getting anything at all of reality. And it’s that possibility of not getting anything at all which has led to Hoffman to embrace his own conscious realism. Yet that’s like stopping eating food simply because one became sick after eating a single mouldy apple.

Mathematics and Idealism

Professor Donald Hoffman endless references (as can be seen in the quotes above) to “the mathematics”, “mathematical models” and “mathematical theorems” seem like a cheap attempt to give his speculative metaphysical position kudos. Hoffman is desperate to show his physics/mathematical credentials — despite holding what many would regard as various wacky or sexy positions. Yet I can’t help feeling that the term “mathematical models” specifically is being used vaguely in Hoffman’s contexts and that such models don’t do the work he claims they do. (The word “model” is often overused and misused outside of physics.)

So it’s as if Hoffman is implicitly saying this:

This can’t be speculative, spiritual and/or sexy because I keep on mentioning mathematics.

In addition, the mathematical models or “formulations” used in conscious realism may indeed be scientific (or mathematical). However, all the additions to that are examples of speculative philosophy. So this isn’t that unlike people using mathematics and scientific terminology to defend — or back up — astrology, astral travelling, ley lines, Creationism, etc. (This aspect of Hoffman’s conscious realism can’t be tackled now. I’ve tackled it here.)

Now for Hoffman’s idealism.

Donald Hoffman’s conscious realism can also be seen as a new-fangled take on idealism — idealism with mathematical and scientific knobs on it.

Hoffman will deny this and he’ll do so for various reasons.

Primarily, Hoffman will do so because he does indeed believe that there is a “reality” out there. (He often uses the word “reality” positively in that he believes that there is a reality; despite the fact that he’s just written a book called The Case Against Reality.) Nonetheless, Hoffman also argues that we haven’t got direct (or even indirect) access to that reality. Instead, we’ve only got access to the contents of consciousness. And that’s still the case even if those contents belong to some kind of collective of consciousnesses (i.e., that of a collective of what Hoffman calls conscious agents).

So Hoffman seems to take a very strong idealist position when he says that “brains and neurons do not exist unperceived”. (This is exactly what Bishop Berkeley argued; thought not, of course, about brains and neurons.) Now this isn’t an expression of anti-realism because an anti-realist wouldn’t argue that any given x doesn’t exist “when unperceived”. He’d simply argue that our perceptions, theories, concepts, languages, etc. “colour” what it is we take to be that x. And there’s no way around that.

Hoffman also has a problem with Immanuel Kant’s position on noumena: he believes that it’s not scientific. Or, less strongly, he believes that Kant’s position doesn’t look promising from a scientific perspective.

As Hoffman puts it about one “interpretation” of Kant:

“This interpretation of Kant precludes any science of the noumenal, for if we cannot describe the noumenal then we cannot build scientific theories of it.”

Yet Hoffman’s own conscious realism isn’t a scientific theory either! (It’s clearly the case that Hoffman believes that it is.) He then says that

“[c]onscious realism, by contrast, offers a scientific theory of the noumenal, viz., a mathematical formulation of conscious agents and their dynamical interactions”.

So if conscious realism really “offers a scientific theory of the noumenal”, then it’s not the noumenal that it’s offering a scientific theory of. Of course this may be terminological pedantry in that, to Hoffman, the noumenal isn’t in fact noumenal at all. Thus he may believe that he can offer a scientific theory of it. Kant, on the other hand, created a theory in which noumena were — almost by definition — not only beyond science, but also beyond Hoffman’s cognitive agents.

Hoffman then expresses a position that isn’t at odds with either anti-realism or Kant’s transcendental idealism. He writes:

“Many interpretations of Kant have him claiming that the sun and planets, tables and chairs, are not mind-independent, but depend for their existence on our perception. With this claim of Kant, conscious realism and MUI theory agree. Of course many current theorists disagree.”

The wording in the above isn’t quite right. Hoffman says that Kant believed that

“the sun and planets, tables and chairs, are not mind-independent, but depend for their existence on our perception”.

Surely it’s best to say that some things (whatever they are) exist mind-independently. The problem is that they don’t exist as the sun, planets, tables and chairs. That is, the fact that we see these things this way is a result of our contingent modes of “perception”; as well as our concepts, theories, languages, etc. However, this is still not idealism because Kantian noumena exist. In addition, they aren’t (at least on most readings) the contents of consciousness. So this is transcendental idealism; not immaterialism or subjective idealism.

Finally, Hoffman has also mentioned Niels Bohr and the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics on a couple of occasions.

It can be argued that Niels Bohr (1885–1962) didn’t really embrace (subjective) idealism. Of course others have strongly argued that he did.

To put it simply: there’s a big difference between Bohr’s stress on how we gain access to (as it were) reality (i.e., through epistemology) and the idealist position that it’s all about what goes on in one’s head. (Or within what Hoffman deems to be a Collective Head.) Most/all anti-realists happily accept that there’s a mind-independent world. However, human beings only gain access to that world through their (contingent) brains, consciousnesses, concepts, languages, etc. Idealists, on the other hand, seems to have it that literally everything is in the minds of subjects (or agents). And, if that’s correct, then that puts idealism and anti-realism in radically different places. Yet, as is the case on so many occasions, anti-realism is basically seen as idealism (or, at the least, as a variety of idealism). Having said all that, Hoffman himself doesn’t make this distinction clear. And, because of that, it can be argued that Hoffman’s position is idealist rather than anti-realist.

Now for Max Tegmark’s (Pythagorean) position that “the universe is mathematical”.

Max Tegmark: The World is Mathematics

The first thing to say is that Max Tegmark’s claim that “the universe really is mathematics” hardly make sense at a prima facie level. It’s not even that it’s true or false. So this must surely mean that it’s all about how we interpret such a claim.

Despite saying that, sometimes it’s hard to express (or even understand) precisely what Max Tegmark’s actual position is. Can we say that reality (or the world) is mathematics or mathematical (as in the “is of identity”)? That reality is made up of numbers or equations? That reality instantiates maths, numbers or equations? Or should we settle for Tegmark’s own very radical words? -

“The Mathematical Universe Hypothesis… at the bottom level, reality is a mathematical structure, so its parts have no intrinsic properties at all! In other words, the Mathematical Universe Hypothesis implies that we live in a relational reality, in the sense that the properties of the world around us stem not from properties of its ultimate building blocks, but from the relations between these building blocks.”

To put the case formally and as clearly as possible: Tegmark believes that physical “existence” and mathematical existence are “one and the same” (which is a phrase he often uses) — i.e., they equal one another. More specifically, Tegmark stresses “structures”. Thus if we have a mathematical structure, it must exist physically as well. Or, more strongly, all mathematical structures exist physically.

The drift of Tegmark’s central position is that the only way we can justify our belief in a mind-independent reality is to accept that it is mathematical. As it stands, of course, that almost seems like a non sequitur. Tegmark does provide some argument for this position; though very little. Indeed only a small part of his Our Mathematical Universe: My Quest For the Ultimate Nature of Reality is devoted to this central thesis.

Tegmark’s position on the mind-independence of reality is different to most positions advanced by metaphysical realists. Reality is not mind-independent in the sense which most metaphysical realists mean. It’s independent of human beings (or minds) simply because it’s an abstract mathematical structure. Thus this has little to do with whether reality is observed; the way it’s observed; its verification; etc. Reality is independent of human beings even if (or when) humans observe it.

So let’s sum that basic argument up:

i) Mathematics is mind-independent.

ii) All non-mathematical descriptions of reality are mind-dependent.

iii) Therefore in order to achieve a true mind-independent description of reality, one must use only mathematics (or mathematical structures) to do so.

One part of Tegmark’s argument (as already hinted at) is that if a mathematical structure is identical (or “equivalent”) to the physical structure it “models”, then they’re one and the same thing. Thus if that’s the case (i.e., that structure x and structure y are identical), then it makes little sense to say that x “models” — or is “isomorphic” with — y. That is, x can’t model y if x and y are one and the same thing.

Tegmark applies what he deems to be true about the isomorphism of two mathematical structures to the isomorphism between a mathematical structure and a physical structure. He gives an explicit example:

electric-field strength = a mathematical structure

Or in Tegmark’s words:

“‘[If] [t]his electricity-field strength here in physical space corresponds to this number in the mathematical structure for example, then our external physical reality meets the definition of being a mathematical structure — indeed, that same mathematical structure.”

In any case, if x (a mathematical structure) and y (a physical structure) are one and the same thing, then one needs to know how they can have any kind of relation to one another. This truism displays this problem:

(x = y) ⊃ (x = x) & (y = y)

In terms of Leibniz’s law, that must also mean that everything true of x must also be true of y. But can we observe, taste, kick, etc. mathematical structures? Yes, I suppose — if physical structures are mathematical structures.

In addition, can’t two structures be identical (i.e., not numerically identical) and yet separate?

All this is perhaps not the case when it comes to mathematical structures being compared to other mathematical structures (rather than to something physical). Yet if the physical structure is a mathematical structure, then that qualification doesn’t seem to work either.

All this is also problematic in the sense that if we use mathematics to describe the world, and that maths and the world are the same, then we’re essentially either using maths to describe maths or the world to describe the world.

In any case, Tegmark’s Mathematical Universe Hypothesis (MUH) is certainly played down by Israel Gelfand, who is quoted saying the following:

“There is only one thing which is more unreasonable than the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics in physics, and this is the unreasonable ineffectiveness of mathematics in biology.”

In the end, then, Tegmark is telling us what physicists have always believed about the importance of mathematics when it comes to describing the world. However, he’s adding the unjustified (Pythagorean) conclusion that both “structures” are one and the same thing.