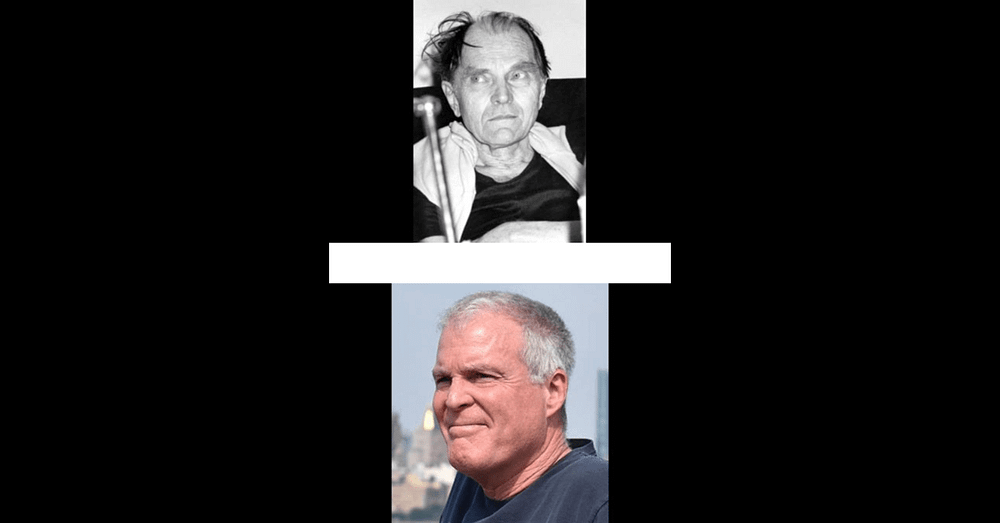

Way back in 1992, the science journalist John Horgan (who writes for Scientific American) interviewed the anarchist philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend. (A full account of this interview can be found in Horgan’s 1996 book, The End of Science.) In that interview, Feyerabend asked Horgan, “What’s so great about knowledge?” He also stated: “‘Truth’ is a rhetorical term.” Horgan himself argued that Feyerabend “objected to scientific certainty for moral and political, rather than epistemological, reasons”.

There are various stories floating around the place about the Austrian philosopher of science Paul Karl Feyerabend (1924–1994). The most popular one was mentioned by the science journalist John Horgan (1953-), who informed his readers that Feyerabend “likened science to voodoo, witchcraft, and astrology”. [See many other references to Feyerabend on voodoo, etc. here.]

In broad and very simple terms (as well as to indulge in Feyerabendian rhetoric), Paul Feyerabend was against truth, knowledge and what people deem to be right… Or, at the very least, he took a political — and perhaps also moral — stance against the people who use these words.

In terms of the word “truth”, Feyerabend believed that it is used in a “rhetorical” way by those people who want to grandstand. As for the thing (rather than the word) knowledge, Feyerabend asked Horgan this question, “What’s so great about knowledge?” Finally, when asked (by John Horgan) if creationism should be taught alongside the theory of evolution in schools, Feyerabend replied, “I think that ‘right’ business is a tricky business.”

Feyerabend’s position on creationism didn’t seem to have much to do with free speech in American schools or diversity of opinion. It was more a way of expressing his position against science. What’s more, it also seems that, just like Steven Jay Gould, Feyerabend had developed a soft spot for religion in his old age… and perhaps before that too. [See my ‘Stephen Jay Gould on Science and Religion: The Politics of Non-Overlapping Magisteria’.] Of course, Feyerabend did tell John Horgan that when he was young he was a “vigorous atheist”. Thus, Feyerabend followed a rather predictable pattern. However, in this interview, he also said that “God is emanations”. He added that he was “not sure [if he was] religious”. Then Feyerabend also stated a theological and cosmological position:

“It can’t be that the universe — Boom! — you know, and develops. It just doesn’t make any sense.”

Now can all this be connected to Feyerabend’s defence of creationism being taught in American schools? It’s hard to say. As it is, John Horgan himself didn’t make this connection in his book.

How to Take Feyerabend’s Words

There are, of course, problems with how to read Feyerabend’s words — especially those statements which can be found outside his technical papers and books. That said, even the titles of his books — such as Against Method (1975) and Farewell to Reason (1987) — seem to have been designed to shock and titillate.

So how should readers take Feyerabend’s words?

As what John Horgan called “Dadaesque rhetoric”? As exhibitionistic contrarianism? As fake scepticism? As being motived entirely by anarchist politics?… Probably, all these descriptions are at least partially correct.

Added to Feyerabend’s rhetoric was the problem that when he was asked to defend his more outrageous statements, he often simply indulged in yet more rhetoric, played word games, or even got bored by the questions. Thus, in these instances at least (i.e., not when it came to his early technical work), Feyerabend was hermetically sealing himself from all criticism with his rhetoric and gameplaying. All that said, he was also honest at times, as when he admitted to Horgan that “[o]f course I go to extremes”, and then explained why he did so.

Some readers may also wonder how Feyerabend’s anarchist politics and rhetoric were influenced by his (to put it bluntly) Nazi upbringing and childhood. That is, did he come to feel guilty about his Nazi past?

After all, anarchistic contrarianism is the exact opposite of Nazism… isn’t it?

Feyerabend’s Nazi past?

Feyerabend’s parents were committed Nazis. Feyerabend himself was in the Hitler Youth (although this was compulsory for most young Austrians), and, later, he served as an officer on the Eastern Front. Indeed, Feyerabend was decorated with the Iron Cross, and he also became a lieutenant.

Of course, many Austrians were Nazis from 1938 to 1945 — so it’s unwise to indulge in smug presentism. However, it is Feyerabend’s retrospective words about this period in his life which are odd and surprising.

For example, Feyerabend stated that he wasn’t concerned with the Anschluss or with World War II, except in the sense that both got in the way of his studies. (They were — to use his own word — “inconveniences”.) Feyerabend also admitted (in his autobiography Killing Time) that, even at a young age (i.e., when a member of Hitler Youth and later) he’d developed a penchant for “contrariness”… although not, apparently, against Nazism.

So, sure, Feyerabend was always a contradictory character. Or as the philosopher of science Ian Hacking put it: “He was fun.”

Now take just one example of Feyerabend’s contradictory character and views.

Is it contradictory that a self-described “epistemological anarchist” spent so much time as an academic who taught at various elite universities? (You can bet that Feyerabend’s fans — as well as some fellow anarchists — would say that there’s no contradiction here at all.) In fact, Feyerabend was a professor for 35 years. (Feyerabend retired in 1992.) However, perhaps he taught his anarchism — if sometimes obliquely — when he taught his philosophy of science.

Alternatively, perhaps an epistemological anarchist (rather than a political anarchist) simply (as it were) practices his anarchism in a university setting, as well as in his papers and books. (Feyerabend did arrange for various leftleaning political activists — not only anarchists — to speak at the universities he taught at, as he stated in his autobiography.)

In any case, John Horgan himself picked up on the various contradictions in both Feyerabend’s actions and in his words (as will be shown). Yet, I suppose, the usual riposte here will be: “We’re all contradictory creatures!”

Feyerabend on the Scientific Method

There’s much to agree on when it comes to Paul Feyerabend’s philosophy of science.

For example, there are indeed reasons to be “against method”, at least when that rhetorical phrase is qualified.

In detail. It’s very easy to find talk of “the scientific method” as being odd and even downright false. More clearly, it’s the use of the definite article “the” that’s jarring.

Specifically, one can agree with Feyerabend when he said the following:

“You need a toolbox full of different kinds of tools. Not only a hammer and pins and nothing else.”

It can be assumed, perhaps ironically, that many scientists would actually agree with Feyerabend on this. Indeed, talk of “the scientific method” seems like a typical example of philosophers foisting their views (or least attempting to do so) on what science is on both scientists themselves and on the general public.

[John Horgan had noted the normative — or even stipulative — nature of Karl Popper’s philosophy of science in a proceeding section of his book. That section is called ‘Karl Popper finally answers the question: Is falsifiability falsifiable?’.]

The problem here is that from the argument that there’s no single scientific method, Feyerabend concluded that “anything goes”.

Now that simply doesn’t follow.

So was this yet another rhetorical and exhibitionistic phrase from Feyerabend?

If Feyerabend had simply — and only — meant that there are many tools in science’s toolbox, then that’s (obviously) true. However, Feyerabend went much further than that. Indeed, he went further in an almost exclusively political direction.

For example, does it follow from the fact that because there is no (as it were) Platonic Scientific Method, that science isn’t (to use Horgan’s words) “superior to other modes of knowledge”? And does it also follow from this that science only (to use Feyerabend’s words) “provides [] stories” on a par with those of historical “mythmakers”?

Was Feyerabend Against Truth and Knowledge?

There are good reasons to ask if Feyerabend was an early example of a poststructuralist or postmodernist player of games (say, in the manner of Jean Baudrillard or Jacques Derrida).

Take John Horgan’s words:

“His talent for advancing absurd positions through sheer cleverness led to a growing suspicion that rhetoric rather than truth is crucial for carrying an argument. ‘Truth itself is a rhetorical term,’ Feyerabend asserted. Jutting out his chin he intoned, ‘I am searching for the truth.’ Oh boy, what a great person.’”

Would Feyerabend have said (or simply believed) that his statement “Truth’ itself is a rhetorical term” is true? Or is it simply and purely a rhetorical statement? However, if it’s neither of these, then what, exactly, is it?

Similarly, was Feyerabend (just like Socrates’s “I know that I know nothing”) trying to show what “a great person” he was by being so deeply committed to truth that he would even dare to question it, and then say that the word truth itself is a “rhetorical term”?

Of course, Feyerabend may have been partially right.

Some people do indeed used the word “truth” rhetorically, just as many people use the word “scientism”, “materialism” and “reductionism” rhetorically.

So was Feyerabend’s statement about the word “truth” at all philosophical?

What’s more, not all people do use the word “truth” in that way.

Actually, how did Feyerabend know who did — and who didn’t — use the word “truth” rhetorically?… Unless, that is, he believed that everybody did!

So this is where we see the problem with Feyerabend’s rhetoric and crude generalisations.

Now what about Feyerabend on knowledge?

In this interview with John Horgan, Feyerabend also indulged in some positive (Jean-Jacques Rousseau-like) Orientalism in relation to knowledge. Horgan wrote:

“Feyerabend noted that many non-industrialized people had done fine without science. The !Kung bushmen in Africa ‘survive in surroundings where any Western person would come in and die after a few days’, he said.”

Sure… and many non-industrialized people have starved to death on mass (i.e., in pre-colonial times), died of terrible diseases, waged continuous war with their neighbours, committed genocide, indulged in mass ritual sacrifice, etc.

In response to John Horgan’s statement about ignorance, Feyerabend replied:

“‘What’s so great about knowledge. They are good to each other. They don’t beat each other down.’”

So did Feyerabend have knowledge that the !Kung bushmen were “good to each other”, and that they didn’t “beat each other down”? Or did he simply believe or even feel this? What’s more, was his belief or feeling (i.e., if it wasn’t knowledge) simply a useful weapon of his anarchist politics?

Horgan picked up on this too. He wrote:

“Wasn’t there something contradictory about the way he used all the techniques of Western rationalism to attack Western rationalism?”

According to Horgan, Feyerabend “refused to take the bait”. Instead, Feyerabend replied by saying,

“‘Well, they are just tools, and tools can be used in any way you see fit.’”

What on earth does that mean?

Perhaps it doesn’t really mean anything.

However, even if it does mean something, then it still doesn’t get rid of the contradiction which Horgan noted. Thus, perhaps that explains why Feyerabend “seemed bored [and] distracted” by Horgan’s questions.

So where do Feyerabend’s points about the !Kung bushmen take us?

Are they entirely political?

Moreover, would anyone even deny that “non-industrialised people” have indeed survived without cars, electricity, the Internet, a National Health Service, modern medicine, democracy, reading Feyerabend’s Against Method, etc.

Science and its Political Uses and Applications

Above it has already been argued — as well as hinted at — that politics was in the driving seat when it came to Feyerabend’s philosophy of science.

John Horgan seems to have taken this position too when he wrote that Feyerabend

“objected to scientific certainty for moral and political, rather than epistemological, reasons”.

In more detail, Feyerabend

“attacked science because he recognised — and was horrified by — its power, its potential to stamp out the diversity of human thought and culture”.

To sum this situation up.

It can be argued that Feyerabend used his “epistemological reasons” against science as weapons to legitimise his political positions against science. In other words, the technical stuff (which readers can find in Feyerabend’s early academic papers) was but a means to a political end.

However, despite Feyerabend using philosophical analysis to give some technical and academic meat to his political problems with science, he still had a point. Or, more accurately, he had a point about the political uses and technological applications of science.

That said, all this seems to be a clear — and very common — conflation of science with the political uses and technological applications of science. Unless, that is, Feyerabend believed that his (to use the word loosely) deconstructions of science itself (if with tools from Anglo-American analytic philosophy) were the best way to do the political job he had in mind. In other words, perhaps Feyerabend believed that it would be much harder to politically misuse and misapply science if science itself (or at least the scientific method) had already been thoroughly deconstructed, if not outrightly (though only intellectually) destroyed.

As already mentioned, Horgan stated that Feyerabend “objected to scientific certainty”.

Yet if the notion of scientific certainty can be objected to for political reasons, then so too can actual scientific theories, scientific data, scientific research projects, etc…

Indeed, they have been!

Thus, if politics is in the driving seat when it comes to the various “critiques” of science, then (to Feyerabend’s words again) “anything goes” if the (righteous) political project, cause or goal demands it. (Of course, anything does go in many areas of politics outside this limited debate about Feyerabend’s philosophy of science.)

So think here of the politicisation of science by the Nazis, the Soviet communists, the Radical Science Movement, etc. Think also of the endless and obvious politics (from all sides!) surrounding “climate science”.

Of course, it must now be acknowledged that many poststructuralist, postmodernist, Marxist, etc. theorists have rejected — and even laughed at — any attempt to argue that there’s a genuine distinction to be made between science itself and its political uses and its technological applications.

More relevantly, then, it’s clear that Feyerabend had a political problem not only with the political uses and applications of science, but also with science itself.

Yet Feyerabend wasn’t averse to many of the applications of science.

John Horgan noted that Feyerabend consulted a doctor when he developed a brain tumour. Feyerabend also lived in a (as Horgan put it) “luxurious Fifth Avenue apartment”, drove a car, earned much more money than the average American, etc. (At the University of Berlin, Feyerabend had two secretaries, fourteen assistants, and an office with an anteroom and antique furniture.)

Still, it can be supposed that someone can hold a strong and principled position against science, and not do a thing about it (i.e., in practice or in his daily life). Perhaps Feyerabend believed that it was enough that he made these political — and rhetorical — statements. Indeed, perhaps Feyerabend believed that it’s up to his followers — or simply those people who believe similar things — to put his anarchist philosophy of science into practice (i.e., outside academic papers and books).

A Note on Feyerabend’s Technical Papers

Feyerabend's technical papers, and how they differ from his rhetorical books and statements, were mentioned earlier in this essay. However, it now needs to be said that even though his technical papers were written in a different prose style, they still cover many of the same philosophical — and sometimes political — issues.

Take the single example of his paper ‘Explanation, Reduction, and Empiricism’, published in 1962. (This was published in the same year as Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.)

I personally discovered this paper in the anthology Philosophy of Science: Contemporary Readings. Out of the many papers included in this anthology, Feyerabend’s own is almost the most technical of all. It’s also one of hardest to read. (It’s a perfect display of academese.) Yet, as already stated, it covers many issues which Feyerabend expressed in much more political and rhetorical ways elsewhere.

In detail.

Feyerabend’s paper is (rather obviously) about “reduction”. (Feyerabend had a serious problem with what he took to be Western reductionism.) This paper also argues against “meaning invariance” and in favour of (Kuhnian?) incommensurability. Feyerabend also stressed the underdetermination of theory by the data, the theory-laden nature of our “perceptions”, and he also argued against what he called “the objective”. More tellingly, Feyerabend even focussed on Aristotle’s philosophy of motion, which was exactly what Thomas Kuhn had done before him (i.e., since 1947).

Of course, many of the ideas found in both Feyerabend's paper, as well as in Kuhn’s work, strongly influenced the mainly political and sociological interpretations (at various later dates) of science which came from various Marxist, postmodernist and poststructuralist theorists. (Remember that Kuhn’s “epiphany” was in 1947, and Feyerabend’s paper was published in 1962.) However, it can be argued — in Feyerabend’s case at least — that these philosophical ideas were actually political from the very beginning. That is, the politics was there even when expressed in the dry analytic prose of Feyerabend’s ‘Explanation, Reduction, and Empiricism’.

The editor of Philosophy of Science: Contemporary Readings, Alex Rosenberg, seems to (at least partially) agree with me on this. He introduced Feyerabend’s paper with the following words:

“Although his earlier (and nowadays largely neglected) works can be viewed as preparing the ground for this attack [i.e., on the very idea that science has a distinctive methodology], they are more moderate and still valuable.”

So are these earlier works by Feyerabend “more moderate” simply because they’re academic papers written for academic journals? In other words, isn’t there a danger here of conflating a certain academic prose style with moderation? After all, isn’t it the case that very many immoderate views have been expressed in a dry academic style?

********************************************

Note:

(1) Since John Horgan writes for Scientific American, it’s worth reading its articles ‘Yes, Science Is Political’ and ‘Science Has Always Been Inseparable from Politics’.

Scientific American took its own overtly political turn when its new editor-in-chief, Laura Helmuth, took over in April 2020. This isn’t to say that there weren’t isolated political articles before that. However, since 2020, entire editions of Scientific American have been explicitly political.

The obvious point to make here is that if any other scientific journal “got” anti-Woke, rightwing, Nazi, conservative, “neoliberal”, libertarian, etc., then those activists (who happen to have degrees in scientific journalism) who want to make Scientific American much more (as the phrase has it) politically committed would be outraged. That said, my bet is that these activists would simply say that these other journals are already political.

Of course, all this is like declaring that science is politics by other means, and that each (as it were) side is simply vying for “hegemony”.

[See Jerry Coyne’s own ‘Scientific American dedicates itself to politics, not science’ and ‘Michael Shermer: How Scientific American Got Woke’.]

My flickr account and Twitter account.