In 2020, Julian Baggini wrote a piece on Jacques Derrida for the magazine Prospect. It’s called ‘Think Jacques Derrida was a charlatan? Look again’. He starts off with a retrospective account of what came to be called “the Cambridge Affair”. In Baggini’s own words: “In May 1992, academics at the University of Cambridge reacted with outrage to a proposed honorary degree from their venerable institution to Jacques Derrida.” Baggini then spends some time on that affair, and has strong words to say against members of what he calls “the Anglo-Saxon academy”. This is my own response to Baggini’s words.

“A certain sort of analytic philosopher who dismisses as meaningless what does not instantly make sense to his shallow pate. [] I coined a name for people like him: ‘philosophistine.’ A philistine out of his depth among real philosophers.”

— Bill Vallicella [See source of quote here.]

Julian Baggini is a British philosopher, writer and journalist. His Prospect article on Jacques Derrida (‘Think Jacques Derrida was a charlatan? Look again’) is relentlessly positive — even deferential. Indeed, even when various criticisms of Derrida are broached, they’re summarily dismissed.

Baggini offers his readers two (if implicit) alternatives:

(1) If readers have made “a serious attempt to read” Derrida, then they’ll realise that he was a (to use Baggini's words) "true philosopher".

(2) If readers believe that Derrida wasn’t a true philosopher (or, worse, if they believe that he was a “charlatan”), then they simply can’t have made a serious attempt to read him.

So, in the light of Baggini’s unceasing positivity toward Derrida, this essay is critical of both Derrida and Baggini himself.

Yet had Baggini expressed at least some qualms about Derrida and his work (he does tackle other people’s qualms), then my own essay will have included at least some positive remarks about the dead French philosopher.

An Event at Cambridge University in 1992

It can be supposed that Julian Baggini simply couldn’t resist mentioning an infamous event which occurred in 1992. He wrote:

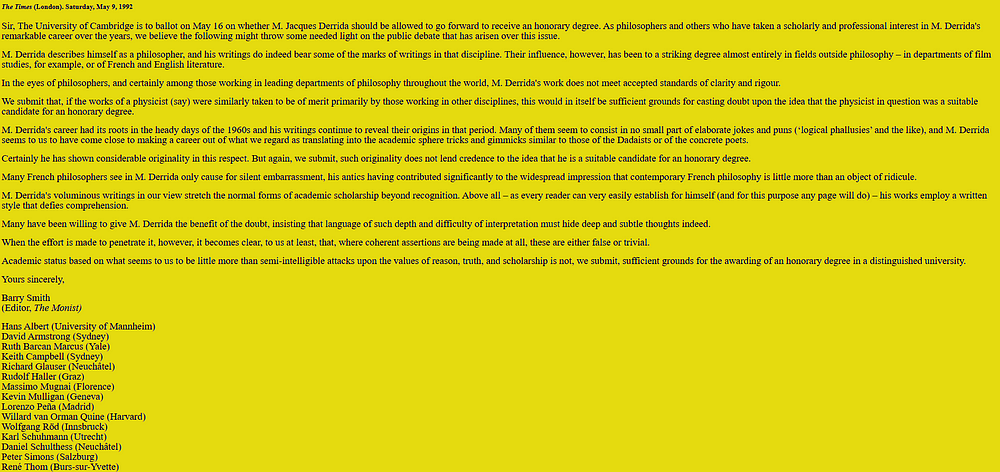

“In May 1992, academics at the University of Cambridge reacted with outrage to a proposed honorary degree from their venerable institution to Jacques Derrida. A letter to the Times from 14 international philosophers followed, protesting that ‘M Derrida’s work does not meet accepted standards of clarity and rigour’.”

Here’s another account (as found in the journal Sophia) from Jeffrey Sims at the University of Toronto:

“Conscientious objection from Professor Barry Smith and 18 others ensured a period of debate in the English press pertaining to issues of academic freedom, and academic responsibility. [] Smith’s letter to The Times is congruent with the efforts of four senior dons who announced a ‘non placet’ vote when the proposed degree was originally announced in March, 1992. The declarations came from David Hugh Mellor [who’ll be discussed later], Ian Jack, Raymond Ian Page, and Henry H. Erskine-Hill.”

Baggini himself continues by telling us that

“[t]o them Derrida was a peddler of ‘tricks and gimmicks,’ a cheap entertainer whose stock in trade was ‘elaborate jokes and puns.’”

Baggini doesn’t seem to have much time for analytic philosophers or what he calls “the Anglo-Saxon academy”. (As opposed to Derrida’s Latin Academy? Or, say, the Teutonic Academy of Martin Heidegger and Paul de Man?) Alternatively and less strongly, is it that Baggini simply doesn’t have much time for those who’re critical of Derrida?

Despite the innuendos, the letter to The Times certainly wasn’t signed by some kind of cabal of snobby and elitist English (or perhaps British) philosophers. (Derrida himself has attracted many elitist and privileged academics.) So Baggini also needs to bear in mind the signatories of the letter against Derrida included Germans, Italians, Spaniards, Austrians, Poles, Dutch, Swiss, etc…

Sure, perhaps they were all “analytic philosophers”, regardless of their nationalities. (I don’t know.)

In any case, that list included the following names:

Hans Albert (University of Mannheim)

Richard Glauser (Neuchâtel)

Rudolf Haller (Graz)

Massimo Mugnai (Florence)

Lorenzo Peña (Madrid)

Wolfgang Röd (Innsbruck)

Karl Schuhmann (Utrecht)

Daniel Schulthess (Neuchâtel)

René Thom (Burs-sur-Yvette)

Jan Wolenski (Cracow)

Added to international nature of these signatories (admittedly, Baggini does use the words “international philosophers” himself) are these words from the letter to The Times:

“Many French philosophers see in M. Derrida only cause for silent embarrassment, his antics having contributed significantly to the widespread impression that contemporary French philosophy is little more than an object of ridicule.”

Indeed, even a fan of Derrida (a Professor E.S. Schliesser) had the following to say about the signatories:

“They are an eclectic mix of anglo-phone analytical philosophers, anglo-phone ‘analytical’ historians of 19th and 20th century philosophy, European and anglophone Husserlians, European ‘Austrian’ philosophers, European analytical philosophers, and a few whom I wouldn’t know how to characterize.”

Have Derrida’s Critics Read Derrida?

More relevantly, Baggini informs us that

“Salmon concludes that ‘none of them had taken the time to read any of Derrida’s work’”.

Baggini himself claims that

“[i]t would have been understandable if some had tried but quickly given up”.

Indeed, almost all the defenders of Derrida have simply assumed that none of the signatories had read Derrida.

For example, there’s a podcast called ‘Judging Philosophers You Haven’t Read’ on the “Cambridge Affair”. Then there’s Terry Eagleton’s article for the Guardian newspaper (called ‘Don’t deride Derrida’), in which he wrote the following:

“English philistinism continues to flourish [] Either they hadn’t read him, or they believed his work was to do with words not meaning what you think they do [].”

[See note.]

The American philosopher John D. Caputo didn’t claim that the signatories hadn’t read Derrida at all. Instead, according to Jeffrey Sims, he was

“ready to celebrate the idea that many of those found on Smith’s list of signatories may not have even read Derrida adequately”.

“Adequately”? What does that mean?

Should they have read Derrida to such an extent that they became positive about the French philosopher?

So how long does that take?

Now take these words from the podcast ‘Judging Philosophers You Haven’t Read’ mentioned earlier:

“How many of his books had they read? [] I’ve read about a dozen of them [] I seriously doubt that most of the signatories to the letter had read more than a smattering of Derrida’s work. Most of them would have likely read one or two of his books (more likely skimmed it), failed to understand what they were reading [] lost patience and probably their temper, and quickly stopped reading.”

In any case, Sims says that it “might be [] reasonable” to ask such questions about the signatories. However,

“it may be difficult for Caputo to know just how much of Derrida these philosophers have actually read”.

Yet the claim that the signatories of the letter (perhaps all of Derrida’s critics) haven’t read Derrida is simply false…

That’s right — false!

Sims continued:

“Clearly, as Barry Smith points out, some have read more of Derrida (J. Claude Evans, John Searle, and Kevin Mulligan) while others admit to having read less.”

Again, how much time should these philosophers have spent on Derrida?

As much time as Julian Baggini?

As much time as a biographer of Derrida, such as Peter Salmon himself?

As for the main signatory of the letter, Professor Barry Smith, he said:

“Certainly some of the many criticisms of Derrida’s work are not based on a scholarly understanding of the relevant literature to which Derrida is reacting. But I have endeavoured to be a serious critic of Derrida. I have taken the trouble to read his work [].”

And, in response to the question “What exactly were you reading [when Smith was in his 20s and 30s] in terms of French thought?”, Barry Smith replied:

“Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, Foucault, Camus []. But I rapidly became more and more interested in Central and Eastern European philosophy, and more specifically in Austrian philosophy. Over the years I became friendly with quite a number of philosophers in Eastern Europe. I collaborated with a number of people in Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic (as it is now called), and I travelled a lot there, as well as in Austria and Germany.”

Now take Eric Schliesser’s words again:

“It is sometimes noted that it is extremely unlikely that most of the signers had read much more of Derrida than I had by the time I left graduate school. What is not noted is that it is extremely unlikely that these signers had read much of each other.”

As for the other critics of Derrida who signed the letter to The Times: had they read Derrida?

Isn’t it obviously the case that those philosophers who’ve sniffed what they believe to be a lot of (to use Hugh Mellor’s word) “bullshit” in Derrida’s work, won’t have wanted to spend too much time on him?

So how much time did Derrida spend on, say, the Anglo-Saxon W.V.O. Quine?

And how much time has Peter Salmon spent on, say, Bas van Fraassen, Jaakko Hintikka, or Hugh Mellor?

I suppose the argument here would be that Derrida didn’t write a letter to The Times stating his (negative) views about another philosopher.

And neither has Peter Salmon.

That’s true… Well, Derrida and Salmon didn’t do so to The Times anyway.

However, I’ve come across a hell of a lot of poststructuralists, postmodern philosophers, “theorists”, etc. who’re fiercely critical of analytic philosophy, yet who’ve hardly read a word of it.

So it works both ways.

Baggini himself provides no evidence that the signatories hadn’t read Derrida. Indeed, all this (as least as far as Baggini’s article is concerned) seems to be a conclusion based on a reference to the term “logical phallusies”, which these supposedly ignorant analytic philosophers claimed Derrida used in a letter.

In the book which Baggini was reviewing in his Prospect article (An Event, Perhaps: A Biography of Jacques Derrida), Peter Salmon says that Derrida never used such a term.

So what about the actual use of that term “logical phallusies” itself?

This is the passage from the original letter to The Times:

“Derrida’s career had its roots in the heady days of the 1960s and his writings continue to reveal their origins in that period. Many of them seem to consist in no small part of elaborate jokes and puns (‘logical phallusies’ and the like) [].”

Is this all that Salmon (as well as Baggini) have to go on?

This reference to “logical phallusies” was hardly the sole basis of the philosophers’ case against Derrida. It was something said in passing — and in parenthesis! — in a single letter. However, because Peter Salmon is a biographer of Derrida and a loyal fan, he picked up on this.

Baggini himself also says that

“[t]he irony is that the protests showed a shocking lack of rigour themselves”.

Sure, perhaps a lack of research when it came to a single term.

However, is this single misattribution really that relevant in this overall debate about Derrida?

Perhaps all Peter Salmon is showing us is that he’s a scholar of Derrida, whereas most of Derrida’s critics… aren’t scholars of Derrida. Thus, like all experts, Salmon probably found it very easy to spot mistakes (or a single mistake in a single letter) when it came to the minutiae of Derrida’s biographical detail.

Hugh Mellor on Jacques Derrida

Now take the case of one philosopher associated with this (as it were) campaign against Derrida — Hugh Mellor (D.H. Mellor).

As already quoted, Mellor was one of the

“four senior dons who announced a ‘non placet’ vote when the proposed degree was originally announced in March, 1992”.

Mellor stated that Derrida

“is a mediocre, unoriginal philosopher — he is not even interestingly bad”.

What’s more, Mellor added that it had been “a bad year for bullshit in Cambridge”.

More relevantly, Mellor had read Derrida!

Take the following words from Mellor:

“Some of Derrida’s early work was interesting and serious. But this isn’t the work he has become famous for, and which led to him being put forward for an honorary degree. That is much later work which seems to me wilfully obscure.”

Of course, Mellor might have got Derrida wrong or simply been uncharitable.

Alternatively, he might simply not have been able to understand him correctly. (Perhaps he should have got Derrida via people like Julian Baggini or Peter Salmon.)

Mellor then gave his reasons for his “‘non placet’ vote”:

“If you spell out these later doctrines plainly, it becomes clear that most of them, if not false, are just trivial.”

Indeed, that sentiment can be found in the original letter (not written by Hugh Mellor) to The Times:

“When the effort is made to penetrate it, however, it becomes clear, to us at least, that, where coherent assertions are being made at all, these are either false or trivial.”

Mellor himself then cited an example:

“Take the fact that the writing down of a signature must have been present at whatever time in the past it was done. Now you can make this truism sound mysterious, as Derrida does. But there’s nothing mysterious about it: it’s just trivially true that if an action leaves a trace, then the trace will always be of something in the past that was once present.”

Now readers can be very sure that Peter Salmon will fault all this. However, it at least shows that Mellor had (tried to?) read Derrida.

In any case, Mellor concluded in the following way:

“So one objection is that Derrida goes in for mystery-mongering about trivial truisms. But he also mixes these truisms up with silly falsehoods, which, if believed and acted on, would cripple intellectual activities of all kinds.”

All the above may well be wrong. (Derrida’s ideas will be discussed in the next essay.)

It may be naïve.

It may itself be (to use Mellor’s own word again) “bullshit”.

What’s more, some of the things Mellor says on this subject I disagree with.

However, Mellor had read Derrida.

Conclusion

On a personal note, I’ve been attempting to understand Derrida since the late 1990s. So perhaps that partially explains one major problem here.

Oddly enough, Julian Baggini acknowledges this when he admits that Derrida was a (well) show-off. Or, at the very least, Baggini quotes Derrida saying (of himself) that he was an “an incorrigible hyperbolite,” and that he would “always exaggerate”. Yet, of course, Baggini immediately (as it were) takes that back when he says that “[y]ou can see why Derrida’s writing could never have been clear and plain”. What’s more:

“Hence Derrida’s difficult style, far from being an affectation, is an inevitable requirement of his philosophy.”

All that said, my own lack of understanding can be explained in three — and probably more - ways:

(1) I’m (philosophically) dumb, I have a “shallow pate”, and/or I’m one of Terry Eagleton's “philistines”.

(2) I’m biased and prejudiced against Derrida.

(3) Derrida designed his prose (or his actual philosophy) to be only partially understand. What’s more, there isn’t that much to understand anyway, and what can be understood is often (to use Hugh Mellor’s word again) “trivial”.

As for the philosophers who signed the letter to The Times.

Perhaps some (even all) of them were merely being tribal in their criticisms of Derrida.

However, they don’t seem to have been nearly so tribal as Julian Baggini, Peter Salmon, Terry Eagleton, etc. have been in their responses to the now infamous “Cambridge Affair”. After all, words such as “English philistinism continues to flourish”, “Anglo-Saxon academy”, “it would have been understandable if some had tried [to read Derrida]”, “a shocking lack of rigour”, “none of them had taken the time to read any of Derrida’s work”, “remarkably sloppy”, “[John Searle] was snide and condescending”, etc. are hardly conducive to fostering dialogue and debate.

As stated earlier, it works both ways.

Note

(1) Terry Eagleton’s words about Derrida’s critics believing that “his work was to do with words not meaning what you think they do” are truly a (to use his own term about Derrida’s critics) “bone-headed” response to the philosophers who signed the letter to The Times. I doubt that a single philosopher has come even close to holding that position on Derrida’s work.

(*) See my ‘Philosopher Julian Baggini on Derrida and the Anglo-Saxon Academy’.

My flickr account and Twitter account.