The following essay is a commentary on — and reaction to — Margaret Boden’s book AI: Its Nature and Future. In this book Boden discusses various technological, scientific and philosophical issues raised by artificial intelligence. Specifically, she tackles the issue of whether programs could ever be “genuinely intelligent, creative or even conscious”.

This essay isn’t a book review.

Part One:

Part Two:

As for my essay, I’ll be focussing specifically on what Boden has to say on consciousness. However, I’ll be placing this subject within the context of artificial intelligence (AI), which forms the basis of Boden’s own book.

Margaret A. Boden was born in 1936. She’s a Research Professor of Cognitive Science who’s worked in the fields of artificial intelligence, psychology, cognitive science, computer science, and philosophy.

She was awarded a PhD in social psychology (her specialism was cognitive studies) by Harvard in 1968. Boden became a Fellow of the British Academy in 1983, and served as its vice-president from 1989 to 1991. In 2001, Boden was appointed an OBE for her services in the field of cognitive science.

Part One

Margaret Boden on Consciousness… and Zombies

Given that Margaret Boden moves on to discuss consciousness in her book AI: Its Nature and Future (i.e., pages 120 to 146), it was almost inevitable that she’d also discuss zombies. (In the literature, philosophical zombies.)

Boden tells us that for the American philosopher Daniel Dennett and the philosopher and researcher (i.e., on artificial intelligence) Aaron Sloman (whom Boden mentions a fair few times in her book), “the concept of zombie is incoherent”.

[See note 1 on the words “incoherent” and “meaningless”.]

Why is that?

Boden continued:

“Given the appropriate behaviour and/or virtual machine, consciousness — for Sloman, even including qualia — is guaranteed. The Turing Test is therefore saved from the objection that it might be ‘passed’ by a zombie.”

Many would deem this to be an account of a very-crude type of behaviourism. That’s even if, in this instance, it’s being applied to a zombie, and also includes a reference to a “virtual machine”.

In detail.

To argue that

“[g]iven the appropriate behaviour and/or virtual machine, consciousness [] is guaranteed”

is surely a behaviourist position. [See note 2.]

Is such “appropriate behaviour” or the relevant “virtual machine” what consciousness is?

Alternatively, does such appropriate behaviour or the relevant virtual machine bring about consciousness?

It will be seen later that the virtual machines must be implemented in physical media — despite their (as it were) virtuality. As for behaviour (including verbal behaviour) being what consciousness is, that seems almost impossible to accept.

Is it, then, that a virtual machine can manifest (or instantiate) consciousness — regardless of behaviour and physical implementation? In other words, is consciousness simply something that some virtual machines could (as it were) have? And if some virtual machines could have consciousness, then they could also display certain types of behaviour (including speech).

Boden’s argument is that virtual machines are (not can be) physically implemented in brains, as well as in much else.

In the context of consciousness and behaviour, Boden also mentions the Turing Test.

The position she present can be summed up in the following way:

If a machine behaves (or acts) as if it is intelligent, then it is intelligent.

Or more in tune with the Turing Test itself:

If a machine answers the requisite amount of questions correctly, in the requisite amount of time, then it is intelligent.

… But what has all this to do with consciousness?

Sure, this questioning-and-answering may well show us that a machine (or zombie?) is intelligent, but Boden also uses the words

“[g]iven the appropriate behaviour and/or virtual machine, consciousness [] is guaranteed”.

in her book.

That’s because if this kind of behaviour is manifested, then consciousness must also be manifested. Therefore, this stance on consciousness becomes true by definition. That is:

(i) Behaviour x is always a manifestation (or instantiation) of consciousness.

(ii) Machine A (or zombie B) behave in way x.

(iii) Therefore, machine A (or zombie B) must manifest (or instantiate) consciousness.

Non-Physicalism, Brains, and Virtual Machines

Margaret Boden mentions Aaron Sloman again. This time in reference to consciousness and qualia.

Aaron Sloman’s position (at least as presented by Boden) may be appealing to some anti-physicalists and anti-reductionists in that he argues that you can’t “identif[y] qualia with brain processes”. What’s more, consciousness and qualia “can’t be defined in the language of physical descriptions”. Yet, despite all that, qualia still “have causal effects”.

This position is still a kind of reductionism in that qualia are reduced to “computational states”. It just so happens that these computational states must also be “implemented in some underlying physical mechanism”.

A hint of this necessary requirement for physical implementation (to be discussed later) can be seen in the following passage from Boden:

“For computational states are aspects of virtual machines: they can’t be defined in the language of physical descriptions. But they can exist, and have causal effects, only when implemented in some underlying physical mechanism.”

Admittedly, to some readers it may seem obvious that physical implementation is required. However, to those AI theorists with a more Pythagorean or even dualist disposition (see later section), it may not be obvious. Alternatively, it may simply need stating to them.

So is this token physicalism (or even token reductionism) in that a virtual “computational state” always requires implementation in a physical mechanism? Again, it just so happens that there’s no single physical medium (so such AI theorists believe) that’s required to bring about consciousness.

Yet consciousness is still brought about via physical implementation.

So it doesn’t really seem to matter that virtual machines have a physically neutral and abstract “computational description” which (as it were) allows them to also be implemented in, say, a set of coke cans or in silicon.

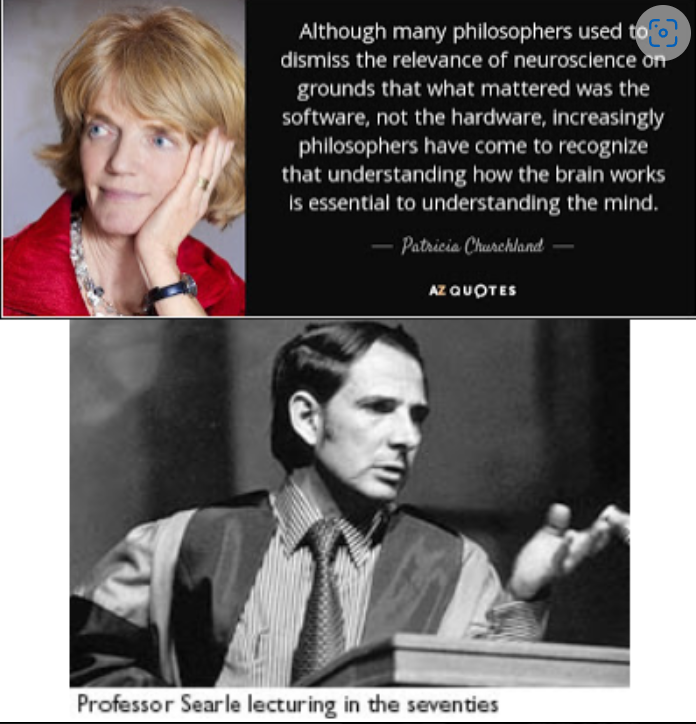

Now this is a good place to introduce Patricia Churchland and John Searle into this philosophical fray.

Part Two

Patricia Churchland on Why Brains Matter

The Canadian-American philosopher Patricia Churchland believes that biology (or physical implementation) matters when it comes to consciousness.

Churchland's position is similar to Gerald Edelman’s, who also said that the mind (if not consciousness)

“can only be understood from a biological standpoint, not through physics or computer science or other approaches that ignore the structure of the brain”.

[Gerald Edelman was a biologist and Nobel laureate.]

Churchland herself takes Edelman's position to its logical conclusion when she (more or less) argues that in order to build an artificial brain, one would not only need to replicate the biological brain’s functions: one would also need to replicate everything physical about it.

Indeed, Boden herself mentions the complete replication of the human brain a couple of times in her book.

For example, she writes:

“If so, then no computer (possibly excepting a whole-brain emulation) could have phenomenal consciousness.”

Churchland has the backup of the American philosopher John Searle here. Searle writes:

“Perhaps when we understand how brains do that, we can build conscious artifacts using some non-biological materials that duplicate, and not merely simulate, the causal powers that brains have. But first we need to understand how brains do it.”

Of course, it can now be said that we may be able to have an example of artificial consciousness without also having an artificial brain. Nonetheless, isn’t it precisely this position which many dispute?

In any case, Churchland says that

“it may be that if we had a complete cognitive neurobiology we would find that to build a computer with the same capacities as the human brain, we had to use as structural elements things that behaved very like neurons”.

She continues:

“[T]he artificial units would have to have both action potentials and graded potentials, and a full repertoire of synaptic modifiability, dendritic growth, and so forth.”

It gets even less promising when Churchland says that

“for all we know now, to mimic nervous plasticity efficiently, we might have to mimic very closely even certain subcellular structures”.

Put that way, Churchland makes it seem as if artificial consciousness (if not artificial intelligence) is still a pipe dream.

Churchland then sums up this big problem by saying that

“we simply do not know at what level of organisation one can assume that the physical implementation can vary but the capacities will remain the same”.

That’s an argument which says that it’s wrong to accept the implementation-function (to use a phrase from Jacques Derrida) “binary opposition” in the first place. However, that’s not to say — and Churchland doesn’t say — that it’s wrong to concentrate on virtual machines, functions or cognition generally. It’s just wrong to completely ignore the “physical implementation” in brains. Or, as Churchland herself puts it at the beginning of another paper, it’s wrong to “ignore neuroscience” and focus entirely on function.

It’s worth bringing in John Searle again here.

John Searle on Why Brains Matter

John Searle once wrote the following words:

“For decades, research has been impeded by two mistaken views: first, that consciousness is just a special sort of computer program, a special software in the hardware of the brain; and second that consciousness was just a matter of information processing. The right sort of information processing — or on some views any sort of information processing — would be sufficient to guarantee consciousness.”

Searle continued:

“[I]t is important to remind ourselves how profoundly anti-biological these views are. On these views brains do not really matter. We just happen to be implemented in brains, but any hardware that could carry the program or process the information would do just as well.”

He then concluded with these words:

“I believe, on the contrary, that understanding the nature of consciousness crucially requires understanding how brain processes cause and realize consciousness.”

Oddly, Searle accuses many of those who accuse him of being a “dualist” of being…well, dualists.

Searle’s basic position on this is the following:

i) If AI theorists ignore (or simply play down) the physical biology of brains (or, in this essay’s case, the precise types of implementation of virtual machines),

ii) then that will surely lead to some kind of dualism in which non-physical abstractions (or virtual machines and “their” computations) basically play the role of Descartes’ non-physical and “non-extended” mind.

The position Searle is arguing against is expressed by Margaret Boden herself in the following way:

“As an analogy, think of an orchestra. The instruments have to work. Wood, metal, leather, and cat-gut all have to follow the laws of physics if the music is to happen as it should. But the concert-goers aren’t focussed on that. Rather, they’re interested in the music.”

In this passage from Boden, it can be seen that concert-goers (at the least) aren’t denying that “instruments have to work”, or that they’re made out of “metal, leather, and “cat-gut”. It’s just that they only care about “the music”.

Is this the same kind of thing with Aaron Sloman and other AI theorists who only care about virtual machines and their computational states?

So can there be music and consciousness without physical instruments and physical machines?

On a different tact.

Searle himself is simply noting the radical disjunction created between the actual physical reality of biological brains (or hardware implementations in Boden’s case), and how many AI theorists explain and account for mind and consciousness.

However, it must be stressed here that Searle doesn’t believe that only biological brains can give rise to minds, consciousness and understanding. Searle’s position is that, at present, only biological brains do give rise to minds, consciousness and understanding.

Searle is therefore simply emphasising an empirical fact. In other words, he’s not denying the logical and metaphysical possibility that other things could bring forth mind, consciousness and understanding.

Of course, the people just referred to (who’re involved in artificial intelligence, cognitive science generally and the philosophy of mind) aren’t committed to what used to be called the “Cartesian ego”. (They don’t even mention it.) This means that the charge of “dualism” seems to be a little unwarranted. However, someone can be a dualist without being a Cartesian dualist. Or, more accurately, someone can be a dualist without that person positing some kind of non-material substance (formerly known as the Cartesian ego).

That said, just as the Cartesian ego is non-material and non-extended (or non-spatial), so too are the (as Searle puts it) “computational operations on formal symbols” which are much loved by those involved in AI, cognitive science and whatnot.

Now let’s return to Aaron Sloman.

Roger Penrose on Why Brains Matter

The least that can be said about Aaron Sloman’s position (as discussed earlier) is that it isn’t dualist… in the traditional sense of that word. That said, Sloman’s stress on computational (therefore mathematical) states may, instead, come across as Pythagorean in nature.

Yet again, these (as it were) Pythagorean states still need to be physically implemented. That is, they may well exist in a pure abstract (platonic?) space. However, when they (as it were) come along with consciousness, then they must be physically implemented.

So the English mathematician and mathematical physicist Roger Penrose may seem like an odd person to bring in here. However, he particularly picked up on (what he deemed to be) some of the (hidden) Platonist assumptions of most AI theorists and some philosophers.

Roger Penrose, specifically, raises the issue of the physical (what he calls) “enaction” of a (in his case) algorithm. He wrote:

“The issue of what physical actions should count as actually enacting an algorithm is profoundly unclear.”

Then this problem is seen to lead — logically — to a kind of Platonism.

Penrose continues:

“Perhaps such actions are not necessary at all, and [] the mere Platonic mathematical existence of the algorithm would be sufficient for its ‘awareness’ to be present.”

Of course, no AI theorist would ever claim that even his Marvellous Algorithm doesn’t need to be enacted at the end of the day. In addition, he’d probably scoff at Penrose’s idea that

“the mere Platonic mathematical existence of the algorithm would be sufficient for its ‘awareness’ to be present”.

Yet surely Penrose does have a point.

If it’s literally all about algorithms or (in this essay’s case) virtual machines (which can be “multiply realised”), then why can’t the relevant algorithms or virtual machines do the required job entirely on their own? That is, why don’t these abstract algorithms or virtual machines automatically instantiate consciousness (to be metaphorical for a moment) while floating around in their own abstract spaces?

To repeat. Penrose’s position can be expressed in simple terms.

If the strong AI position is all about algorithms or virtual machines, then literally any implementation of a Marvellous Algorithm or Marvellous Virtual Machine would bring about consciousness and (in Penrose’s own case) understanding.

More specifically, Penrose focuses on a single qualium (i.e., the singular of ‘qualia’). He writes:

“Such an implementation would, according to the proponents of such a suggestion, have to evoke the actual experience of the intended qualium.”

If the precise hardware doesn’t matter at all, then only the Marvellous Algorithm (or Marvellous Virtual Machine) matters. Of course, the Marvellous Algorithm (or Marvellous Virtual Machine) would need to be implemented… in something. Yet this may not be the case if we follow the strong AI position to its logical conclusion…

Or at least this conclusion can be drawn out of Roger Penrose’s own words.

Notes:

(1) What should we make of the logical-positive-type phrase “the concept zombie is incoherent”? (That’s if Margaret Boden is correctly expressing the positions of Daniel Dennett and Aaron Sloman.)

Well, there may well be very-strong arguments against the concept zombie. (Actually, arguments against what is said about philosophical zombies.) However, that concept doesn’t thereby become “incoherent”. (Or, as the logical positivists once put it about statements, it doesn’t thereby become “meaningless”.)

(2) It can’t be a solely functionalist or even verificationist position either, even if these two isms can easily run alongside behaviourism.

(*) The subject of qualia was mentioned a couple of times in the essay above. See my essay ‘Margaret Boden on Qualia and Artificial Intelligence (AI)’.