“Another benefit of listening to music while reading is that music can help you retain information. This is because listening to music can activate the left part of your brain and the right part of your brain simultaneously. This allows for increased levels of retention and understanding, which can help you read.”

— See source here.

“Yes! I can’t read without music! Honestly, I can’t do anything without music.”

— See source here.

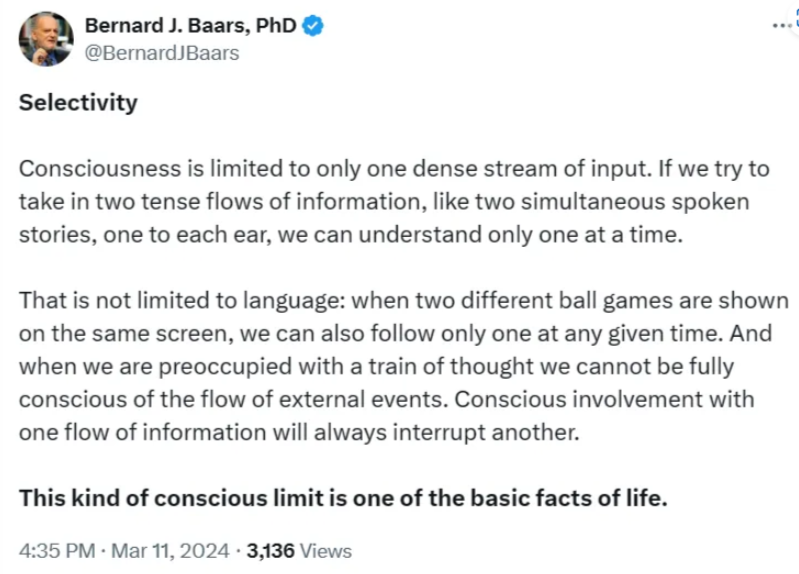

Some readers may wonder how reading (or writing) and simultaneously listening to music fits into Bernard J Baars’s* post above.

Sure, you can’t concentrate as much on the music as you could do if you listened to it exclusively. However, surely these two things do occur together. Indeed, listening to music and reading (or writing) at the same time is a common phenomenon.

Of course, it may be the case that we switch from one to the other. (Baars talks in terms of “once flow of information will always interrupt another”.)

So readers should try a phenomenological experiment here.

Personally, it’s hard to tell if switching is actually going on.

For example, while writing these very words, I’m aware of the music in the background. I must be! I can note the tunes, the harmonies, and even the moods and emotions the music brings about. What’s more, if something very surprising occurred in the music (or a particularly “catchy” bit came up), then I’d immediately notice that. This strongly suggests that I’m (nearly?) always aware of the music while writing…

Actually, surely I am listening to the music while writing!

So, on the surface at least, there’s no total (or complete) switching between writing and listening to the music. (Again, Baars writes: “Conscious involvement with one flow of information will always interrupt another.”) However, there may well be a lesser degree of switching occurring. In other words, the music is less focussed upon than it would be if I were not writing. However, and as already stated, the music is still being listened to.

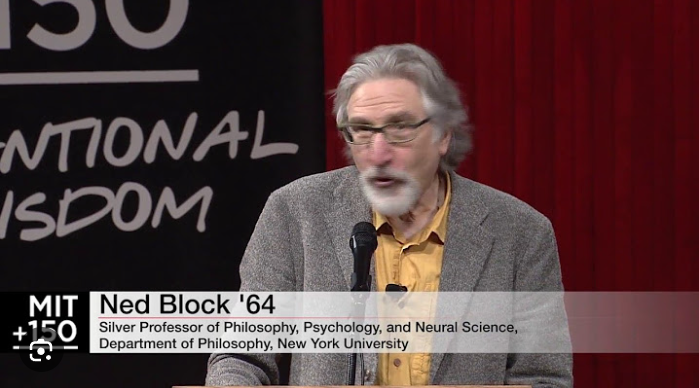

Ned Block on Phenomenal Consciousness and Access Consciousness

All this reminds me of an example from the American philosopher Ned Block. This is of someone writing (or reading), and all along there’s the sound of church bells coming from outside his home. The reader (or writer) hears the church bells at all times. However, only at a certain time does he actually note (a loose word, admittedly) that it’s church bells that he can hear.

As Block puts it: this person is phenomenally conscious of the church bells all along. However, he becomes access conscious of the bells only at a certain point.

The terms of the trade have it that the hearing of the church bells (though not as church bells) is an example of (according to Block again) “phenomenal consciousness without access-consciousness”. (“Access-consciousness” includes the application of concepts — among other things - to “phenomenal consciousness”.)

To clarify. A person can hear church bells, and not hear them as church bells. In other words, concepts may not be applied to all the sounds a person hears. (This way of putting it doesn’t seem to be as easily applicable to my own writing-while-listening-to-music example.)

Are these examples of experiences in the strict sense?

It could be the case that while these sounds are entering consciousness, the mind is applying concepts to other things instead. So the sensory input from the the church bells (or from the “background music”) are in (as it were) outer consciousness. The sounds aren’t experiences in that the mind doesn’t infer anything from them. They’re not, as Block himself puts it, “poised for reasoning”. And they’re certainly not an epistemological “given” because there’s no cognitive awareness of — or relation to — the sounds.

Thus, these sounds can’t be the ground for inferences, knowledge or anything else.

To sum up. Nothing is derived from the sound of the church bells when they’re not heard as church bells.

The philosopher John Searle clarified things a little here.

Searle argued that we can call the sound of church bells (or the music listened to while writing) an example of what happens in “peripheral consciousness”.

The American philosopher Jennifer Church also cited an example of supposed phenomenal consciousness when she wrote the following words:

“Consider the example of a noise that I suddenly realise I have been hearing for the last hour. [Ned] Block uses it to show that, prior to my realization, there is phenomenal-consciousness without access-consciousness.”

This would be an example of Searle’s peripheral consciousness. However, Jennifer Church even denied (or doubted) the possibility of true phenomenal consciousness without access consciousness. She continued:

“[I]t seems that I would have accessed it [the noise] sooner had it been a matter of greater importance — and thus it was accessible all along. Finally, it is not even clear that it was not actually accessed all along insofar as it rationally guided my behaviour in causing me to speak louder.”

This is roughly equivalent to my own example of suddenly paying more attention to the music when, say, some catchy tune pops up. (Or perhaps when the internet connection cuts off the music entirely.)

Ned Block himself comes up with an alternative way of describing this putative before-noon pure example of phenomenal consciousness: “P-consciousness without attention.” I would say, perhaps only as a paraphrase, PC with inattentive AC (access consciousness). To use John Searle’s term again, the noise of church bells before noon (or the music in the background) was mainly peripherally conscious, although never an example of pure phenomenal consciousness.

Strangely enough, while writing some of the words above there was a noise outside my own flat. I didn’t pay attention to it. I was inattentive. (The noise was in peripheral consciousness.) However, I knew all along that it was at least a noise. Indeed, perhaps all along I knew that it was a car alarm. After all, if the car alarm had seamlessly turned into a scream (if you can imagine such a thing), then I would have become more attentive to the noise.

Concluding Note: What About the Brain?

Some readers may wonder how the (as it were) facts of the matter would be established in the cases discussed above. After all, the whole thing is dependent upon my own “verbal reports” (or subjective reports) on what’s going on inside my head. My own personal reports could, of course, be correlated with other people’s verbal and subjective reports on the same issue. And much could be concluded from that. However, we’d still only have various verbal reports about subjective experiences.

So some readers may also wonder (i.e., as non-specialists) what’s going on in the brain to make all this possible. Perhaps neuroscience could provide an answer to the limited scope of all the verbal reports about what subjectively occurs when reading (or writing) and listening to music at the same time.

(*) Bernard J. Baars (born 1946) is a neuroscientist who’s best known as the originator of the global workspace theory. He has worked as a professor of psychology at the State University of New York, Stony Brook.