In this instance, the philosopher J.R. Lucas relied heavily on Kurt Gödel's first incompleteness theorem to advance his position against “mechanism” and “machine minds".

“Does Godel’s incompleteness theorem prove God? The Incompleteness of the universe isn’t proof that God exists. But it is proof that in order to construct a rational, scientific model of the universe, belief in God is not just 100% logical… it’s necessary.”

— Perry Marshal [See source here.]

“Gödel’s work is not overrated in terms of its creativity. It is overrated as to its relevance.”

— Justin Rising [See source here.]

“[Gödel’s theorems have] survived over eighty years of fairly active scrutiny from the mathematical community. That’s as close to a guarantee as you’re going to get.”

— Eugene Bucamp [See source here.]

Is John Lucas’s well-known paper ‘Minds, Machines and Gödel’ a perfect example of Gödel’s incompleteness theorems being overstretched, overused, and overplayed? It’s hard to say. However, Lucas himself said (in another paper) that we can “adapt and apply [the first theorem] in innumerable different circumstances”.

So Lucas’s “Godelian argument” is part of a long and popular tradition.

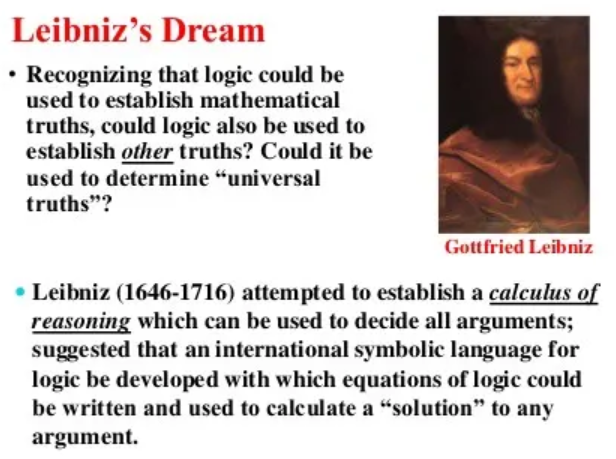

Take the case of the mathematician and educator Morris Kline.

Kline made a grand claim about Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems when (in his Mathematics: The Loss of Certainty) he said that it was a

“response to Leibniz’s 250-year-old dream of finding a system of logic powerful enough to calculate questions of law, politics, and ethics”.

Were Gödel’s theorems really a response to Leibniz’s dream?

Perhaps they were just Gödel’s way of showing mathematicians that… well, axiomatic systems (which are of sufficient complexity to express the basic arithmetic of the natural numbers) can’t be both fully consistent and complete —and that’s it!

Yes, this is a version of Gödel’s theorems without any knobs on them.

So, again, can Gödel’s theorems be applied outside mathematics?

The science writer John Horgan certainly applied them to the theories of physics. Or, more accurately, he told us that Gödel’s

“incompleteness theorem denies us the possibility of constructing a complete, consistent mathematical description of reality”.

Clearly there’s a jump here from Gödel’s incompleteness theorems to physical reality… Or at least there’s a jump from Gödel’s theorems to a “consistent mathematical description of reality”.

Is that jump justified?

Well, there’s certainly no consensus on this issue.

Indeed, Gödel himself wasn’t too keen on applying his theorems to physics — especially to quantum physics. According to the mathematician and theoretical physicist John D. Barrow:

“Godel was not minded to draw any strong conclusions for physics from his incompleteness theorems.”

In addition, the German computer scientist Jürgen Schmidhuber has argued against this fixation on Gödel’s theorems. More clearly, Schmidhuber believes that Gödel incompleteness is irrelevant when it comes to computable physics.

With more relevance to J.R. Lucas’s own Gödelian argument.

Another common supposed result of Gödel’s theorems is the argument that that they demonstrate a limit to artificial intelligence.

Perhaps this is a more feasible idea because it’s about the (meta)mathematical limitations of artificial intelligence — and thus Gödel’s theorems are relevant.

Would an indefinite advance in AI be halted by the results of Gödel’s theorems? After all, they show us (or at least they show some mathematicians and philosophers) that if a mathematical system can’t be both complete and fully consistent, then any project that relies on mathematics (i.e., AI) will never be both complete and fully consistent. Thus, there will be a limit to AI when it comes to artificial minds and/or artificial consciousness.

Returning to the general theme of the wide popularity and use of Gödel’s theorems.

When Gödel is recruited to fight various philosophical and religious causes, what often matters to the fighters is the fact that (in this case at least) the first theorem

“can also be taken as giving us a certain type or style of argument, which we can understand, and, once having got the hang of it, adapt and apply in innumerable different circumstances”.

[See source of quote here.]

Again, all this has meant that highly-technical metamathematical theorems have been extensively used to advance all sorts of philosophical, religious and moral positions.

What’s more, J.R. Lucas himself happily admitted that it’s not literally all about Gödel’s first theorem being taken in its raw form, and then being algorithmically applied to the problem of “minds and machines”.

So let’s tackle John Lucas’s philosophical positions here.

Gödel’s Theorem + Philosophy

In his paper ‘Satan Stultified’ (1968), Lucas wrote the following words:

“The application of Gödel’s theorem to the problem of minds and machines is difficult. Paul Benacerraf makes the entirely valid ‘Duhemian’ point that the argument is not, and cannot be, a purely mathematical one, but needs some philosophical premises to be able to yield any philosophical conclusions. Moreover, the philosophical premises are of very different kinds.”

What were Lucas’s own “philosophical premises”? Or, more accurately, which of his philosophical premises were over and above Gödel’s first theorem, and its strictly metamathematical context?

When it comes to Lucas’s non-metamathematical work, there seems to have been assumptions about the “mechanical” and what it is to be “alive”. (We also need to know what philosophical work Lucas’s hyperbolic word “ossified” is doing.) More importantly, what “philosophical conclusions” do these philosophical premises lead to, and how far do they run free of Gödel’s first theorem?

So here’s Lucas himself on his own philosophical conclusions and assumptions:

“I am concerned with the reductionist thesis that we could in principle give a mechanist deterministic account of human behavior which was complete and left no room for free will, moral responsibility or individual creativity. It is that thesis that the Godelian argument is intended to refute.”

To sum up with a final question.

Did J.R. Lucas use Godel’s first theorem simply as a tool (or even a weapon) to safeguard “free will, moral responsibility [and] individual creativity” from “mechanistic attack”?

Note:

Let’s return to Morris Kline.

As already shown, much has been made of Gödel’s theorems by non-mathematicians and by many non-philosophers. Morris Kline expressed this general idea. He said that we

“might think that Gödel’s proof implies that the rational mind is limited in its ability to understand the universe”.

Again, how could a result in metamathematics do that — even in principle?

The mind must surely be limited in some way. Perhaps that means that it could never understand everything there is to know about an infinite universe. Indeed, this is bound to be the case because only an omniscient mind could know everything there is to know about the universe.

Kline also made the point that

“though the mind may have its limitations, Gödel’s result doesn’t prove that these limitations exist”.

What is limited isn’t the mind as such: it’s that “axiomatic systems are limited in how well they can be used to model other types of phenomena”. This has nothing to do with the mind of man taken generically. It’s to do with axiomatic systems and how they model other types of phenomena.