In the book The Grand Design (2010), Stephen Hawking wrote a passage which has been quoted and memed many times. In it, there’s this line: “Because there is a law such as gravity, the universe can and will create itself from nothing.” The following essay focuses on the word “nothing”, as well as on gravity. Indeed, gravity is given a starring role in Hawking’s own “creation story”.

(i) Introduction

(ii) Spontaneous Creation?

(iii) What Is Gravity?

(iv) Something From Nothing?

(v) Nothing Is Something

(vi) Lawrence Krauss on Nothing

(vii) Philip Goff’s Questions

(viii) David Albert’s Questions

Firstly, let me quote the full controversial passage which this essay will be discussing:

“Because there is a law such as gravity, the universe can and will create itself from nothing. Spontaneous creation is the reason there is something rather than nothing, why the universe exists, why we exist. It is not necessary to invoke God to light the blue touch paper and set the universe going.”

The passage above can be found in the book The Grand Design. This book was written by Stephen Hawking, and co-authored by the American physicist Leonard Mlodinow.

To be fair to Stephen Hawking, the words above aren’t part of a technical physics paper. So Hawking might well have been summing things up in an easily digestible — and even sexy — form…

That said, surely Hawking must still have realised that the idea of the universe “creat[ing] itself from nothing” is philosophically — and even scientifically! — illiterate. Indeed, even a cartoon atheist should have problems with the way Hawking put things.

So I find myself (perhaps reluctantly) agreeing with a creationist by the name of Brian Thomas, who writes for the Institute for Creation Research. Thomas wrote the following words:

“What would compel a person to ascribe the power of creation to just gravity?”

That question just quoted, I certainly don’t agree with everything else Thomas writes in his critical article on Stephen Hawking, especially not his inevitable references to God and Christian theology.

Anyway.

Let’s break the opening passage down as it stands.

(Note: I’ve just written the words “as it stands”. I did so because it will be shown that Stephen Hawking meant something when he used the word “nothing”!… But more on that later.)

Spontaneous Creation?

“Spontaneous creation is the reason there is something rather than nothing, why the universe exists, why we exist.”

The words “spontaneous creation” are just a poeticism. Hawking just stated this. There is no argument here. There is little science. Indeed, in my view, there’s not even much philosophy.

Hawking ended his comments with the following words:

“It is not necessary to invoke God to light the blue touch paper and set the universe going.”

True, “[i]t is not necessary to invoke God” here. Indeed, using God to get out of these problems simply creates innumerable other problems.

(This is the classic fallacy of believing that y must be true, simply because x is false or questionable. [See note 1.])

However, any alternative must at least have its own logic. It must also be scientifically, as well as philosophically, literate.

Have I personally got the answer?

No!

However, there are answers out there…

Sure, whether they work or not is another matter.

What Is Gravity?

“Because there is a law such as gravity, the universe can and will create itself from nothing.

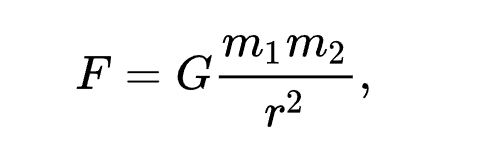

What is gravity anyway?

Commentators, and even scientists, don’t often really say what gravity is. Instead, they tell us what it does.

Gravity isn’t really a thing.

Indeed, on Albert Einstein’s general relativity picture of 1915, gravity isn’t even a force.

Instead, gravity is deemed to be the curvature of spacetime. And this curvature is “caused by the uneven distribution of mass, which causes masses to move along geodesic lines”.

So, in that sense, it’s understandable that we aren’t told what gravity is if (in very simple terms)

gravity = the curvature of spacetime

In that case, take that question again, “What is gravity?”. This contains an assumption which is almost equivalent to assuming that the shape of a banana is a concrete (i.e., not an abstract) thing.

In any case, “What is gravity?” prompts the question, “What is spacetime?”…

So what is spacetime?

Indeed, what is mass?…

Aren’t we going around in circles here?

(As we’ll see later, the philosopher Philip Goff certainly believes that some kind of “classic catch-22” is involved.)

Now let’s take this passage, which actually backs up Hawking’s own position:

“Can gravity create a universe?

“Yes [ ] gravity — a force so constant and ubiquitous that we rarely notice it. Yet without gravity, the universe as we know it could not exist.”

Laypeople can happily accept that “without gravity, the universe as we know it could not exist”. However, they don’t also need to accept Hawking’s statement that “a law of gravity” — on its own! - created the universe.

I’m reluctant to agree with the aforementioned creationist again…

However, I do.

Brian Thomas writes:

“What would compel a person to ascribe the power of creation to just gravity? Perhaps it stems from the idea that gravity has an equal amount of ‘negative’ energy to perfectly balance all other ‘positive’ energies.”

We now need to know what both negative energy and zero energy are.

Let me quote one slightly-more technical take on zero energy:

“In the zero-energy universe model (‘flat’ or ‘Euclidean’), the total amount of energy in the universe is exactly zero: its amount of positive energy in the form of matter is exactly cancelled out by its negative energy in the form of gravity. It is unclear which, if any, of these models accurately describes the real universe.”

So does (or can) negative energy help create nothing when it “perfectly balance[s] all [the] other ‘positive’ energies”?

Let’s return to our creationist again. Thomas continues:

“But even if ‘gravity’ did provide such balance, it could hardly suffice as an adequate cause for the whole universe. Pointing out qualities of already-existing energies is no more an explanation for their origin than pointing out how the energy-of-motion in a rolling ball will be exactly matched by the energy-of-resistance from friction. Neither quantity answers where the ball came from and who or what pushed it.”

The upshot here seems to be that even if negative and positive energies are balanced out, then we still need to contend with the prior existence of “already-existing energies”…

Or do we?

Does it follow that simply because both positive and negative energies previously existed, that their balancing out can’t create (or bring about) nothing?

More simply put in the form of a question:

Is overall energy equalling zero the same thing as it equalling… nothing?

Something From Nothing?

“Because there is a law such as gravity, the universe can and will create itself from nothing.”

A law in (modern) physics is a mathematical abstraction. [See here.] That’s the case even if it’s derived from observations, experiments, tests, etc. (Those observations, experiments, tests, etc. will also have relied on abstract mathematical laws.)

All this means that “a law such as gravity” must be a mathematical abstraction too.

How can a law — on its own — create anything?

To be fair to Hawking, he did seem to recognise — at least at one point — this problem. In A Brief History of Time, Hawking wrote:

“What is it that breathes fire into the equations and makes a universe for them to describe?”

To spell that out, and make it relevant to this essay:

What is it that breathes fire into the laws of physics and makes a universe for them to describe?

Hawking’s words “a law such a gravity” also seem odd from both a grammatical (i.e., they’re not “a law of gravity”) and a scientific point of view. Gravity may be “governed” by a law (or by laws), but surely it isn’t itself a law….

Well, perhaps gravity is a law if one takes a Pythagorean position on this issue. [See here.]

Nothing Is Something

Many readers will already know (or have guessed) that there are slightly-more technical — but still not mathematical — translations of Hawking’s… well, “popular science”. Take this example:

“[Stephen Hawking] means that gravitational potential energy is negative. It balances all the positive energy of mass, motion, heat. [ ] that makes the total energy of the universe zero. So the universe can form from nothing without violating conservation of energy.”

The assumption in that passage seems to be this:

At one point, the “total energy of the universe” equalled “nothing”.

Yet even here gravity is deemed to exist. And gravity isn’t nothing.

We also have “the positive energy of mass, motion, heat”.

Sure, it’s also stated that this positive energy is then “balance[d]” by gravity’s “negative” energy.

Thus, again, is zero universal energy literally nothing?

It turns out, however, that nothing is not… nothing. Or at least that’s what the theoretical physicist Lawrence Krauss believes.

Lawrence Krauss on Nothing

In his book A Universe from Nothing: Why There Is Something Rather than Nothing, Lawrence Krauss wrote the following words:

“Some philosophers and many theologians define and redefine ‘nothing’ as not being any of the versions of nothing that scientists currently describe. But therein, in my opinion, lies the intellectual bankruptcy of much of theology and some of modern philosophy, for surely ‘nothing” is every bit as physical as ‘something,’ especially if it is to be defined as the ‘absence of something.’ It then behooves us to understand precisely the physical nature of both these quantities.”

The upshot here is that (all?) physicists mean something different by the word “nothing” than “some philosophers and many theologians”. (Not that all philosophers and theologians define the word “nothing” in the same way!)

In Krauss’s eyes, nothing has a “physical nature”.

So do Krauss’s words “absence of something” mean the absence of everything?

Well, no, not if nothing is “every bit as physical as ‘something’”. In that case, then, Krauss’s nothing can’t be the absence of everything.

Sure, Krauss’s nothing may well be the absence of people, stars, planets, and even atoms. (What about particles?) However, is it also the absence of gravity, energy, spacetime and the vacuum?

In the long passage above, Krauss also criticises “some philosophers”. (At least, in this instance, Krauss uses the prefix “some”!) This is odd because he indulges in some arcane philosophy himself. Again, Krauss states that

“‘nothing” is every bit as physical as ‘something,’ especially if it is to be defined as the ‘absence of something’”.

Perhaps it’s not really arcane philosophy at all…

But only if, like Krauss, we also believe that nothing is actually something. That is, if only we believe that nothing is something (to use Krauss’s own word) “physical”.

Is nothing… something?

Well, Krauss certainly used the word “nothing” to mean… something.

The philosopher David Z. Albert picked up on this in his review of Krauss’s book. In his article ‘On the Origin of Everything’, Albert wrote:

“And the fact that particles can pop in and out of existence, over time, as those fields rearrange themselves, is not a whit more mysterious than the fact that fists can pop in and out of existence, over time, as my fingers rearrange themselves. And none of these poppings — if you look at them aright — amount to anything even remotely in the neighbourhood of a creation from nothing.”

So although this concern with words and definitions will probably seem boringly philosophical to Krauss, getting these things clear will still take away Stephen Hawking’s earlier sexy punch. (As it was expressed in the opening phrase, “the universe can and will create itself from nothing”.)

It should be said here that it’s not even that we should be against scientists using old words in new ways. Doing that is fine… but only as long as everyone in the discussion knows that this is what’s happening…

But clearly — in this case especially — that isn’t the case!

All that said, Krauss himself acknowledges the difficulties with both his scientific position on nothing, and with his use of the word “nothing”. He wrote:

“Even if you accept this argument that nothing is not nothing, you have to acknowledge that nothing is being used in a philosophical sense. But I don’t really give a damn about what ‘nothing’ means to philosophers; I care about the ‘nothing’ of reality. And if the ‘nothing’ of reality is full of stuff, then I’ll go with that.”

The words “the ‘nothing’ of reality” are about as scientific as the words “the One is the basis of all minds”. So perhaps Krauss used the word “nothing” mainly (or even solely) because it’s sexy. Indeed, he admits “that hook [i.e., A Universe from Nothing] gets you into the book [and] that’s great”. What’s more, Krauss then says that “in all seriousness, I never make that claim”.

Yes, A Universe from Nothing is just a sexy title!…

Now how scientific is that?

So what on earth is going on here?

Or is that a boring philosophical question too, Mr Krauss?

The wider situation here is that both Hawking and Krauss needed philosophy in order to clarify these issues. Thus, because they weren’t philosophically and scientifically clear in their sexy expressions, some (perhaps even many) laypeople will have believed that they’re talking nonsense…

On the other hand, there will be some (perhaps even many) non-specialist defenders of such “popular physicists” who’ll happily swallow all this stuff . That is, the groupies of such physicists will take Hawking’s and Krauss’s words to be gospel!

Philip Goff and David Albert have been mentioned in passing, so it’s worth finishing off with their boringly-philosophical takes on this issue. Indeed, their philosophical questions clearly annoy Krauss, and that’s why he classified Albert as “moronic” (see later).

Philip Goff’s Questions

As stated, most accounts of gravity don’t actually tell you what it is. And, because of that, some readers may be somewhat sympathetic to Philip Goff’s take on this issue.

So let’s quote Goff here…

However, in the following passage, Goff actually discusses mass, not gravity. Yet all the same arguments and statements still seem to apply.

Goff writes:

“What is [gravity]? For a causal structuralist, we know what [gravity] is when we know what it does [ ]. But to really understand what this really amounts to, as opposed to merely being able to make accurate predictions [ ].”

To make it clear what exactly Goff means in the above, he continues with the following words:

“For a causal structuralist, we understand what spacetime curvature is only when we know what it does, which involves understanding how it affects objects with mass. But we understand this only when we know what mass is. We find ourselves in a classic catch-22: we can understand the nature of mass only when we know what spacetime curvature is, but we can understand the nature of spacetime curvature only when we know what mass is.”

David Albert’s Questions

David Albert was mentioned earlier, and he too kinda puts similar positions to Goff — as well as to the creationist mentioned earlier! What’s more, the following passage is from Albert’s review of Krauss’s book A Universe from Nothing. Albert wrote:

“The particular, eternally persisting, elementary physical stuff of the world, according to the standard presentations of relativistic quantum field theories, consists (unsurprisingly) of relativistic quantum fields… they have nothing whatsoever to say on the subject of where those fields came from, or of why the world should have consisted of the particular kinds of fields it does, or of why it should have consisted of fields at all, or of why there should have been a world in the first place. Period. Case closed. End of story.”

As already stated, some of these points and questions are — admittedly — in roughly the same ballpark as the creationist’s earlier. So, sure, these questions are philosophical. Yet they’re philosophical questions which at least some physicists themselves have speculated about. [See here.]

Not so Lawrence Krauss…

Or has he?

Krauss stated the following words, which may — or may not — explain things:

“Well, I read a moronic philosopher [David Albert] who did a review of my book in the New York Times who somehow said that having particles and no particles is the same thing, and it’s not.”

[See note 2 on the “moronic philosopher” David Albert.]

I have no idea what the second half of that passage above means. However, Krauss continued:

“The quantum state of the universe can change and it’s dynamical. [The philosopher David Albert] didn’t understand that when you apply quantum field theory to a dynamic universe, things change and you can go from one kind of vacuum to another. When you go from no particles to particles, it means something.”

I doubt that David Albert would deny that the “quantum state of the universe can change and it’s dynamical”. (That statement is a bit broad and vague as it stands.) I also doubt that Albert would have a problem with the words “when you apply quantum field theory to a dynamic universe, things change and you can go from one kind of vacuum to another”. Perhaps, then, the last sentence is the relevant clincher:

“When you go from no particles to particles, it means something.”

So is going from “no particles to particles” going from nothing to particles?

No.

Why is that?

Because Krauss himself has told us that he means something by the word “nothing”. Not only that: he also told us that “nothing is every bit as physical as ‘something’”!

Apparently, these Koan-like positions are fine because, as Krauss has already told us, he doesn’t

“really give a damn about what ‘nothing’ means to philosophers”.

Krauss’s nothing, on the other hand, is the “‘nothing’ of reality”. Indeed, that ““nothing’ of reality is full of stuff”!

So hopefully this discussion will — at least partially — explain Hawking’s enigmatic and sexy words at the opening of this essay.

Notes:

(1) As another example of this, take the case for idealism and the case against physicalism. Idealists spot what they see as the serious problems with (what they call) “physicalism”. Many of them then simply assume that this is a good enough reason for them to embrace, say, “universal consciousness” or “the One”.

Of course, there are serious problems with idealism too.

This prompts the idea that metaphysical beliefs are at least partly a matter of aesthetic preference. Perhaps they’re under the tutelage and power of prior motivations and beliefs too.

(2) On David Albert:

“[David Albert] received his bachelor’s degree in physics from Columbia College (1976) and his PhD in theoretical physics from The Rockefeller University (1981) under Professor Nicola Khuri. Afterwards he worked with Yakir Aharonov of Tel Aviv University.”