Integrated information theorists postulate a literal identity between consciousness and integrated information. The British neuroscientist Anil Seth rejects this identity.

The British neuroscientist Anil Seth puts the integrated information theory (IIT) position at its most simple when he tells us that

“on IIT information — *integrated* information, Φ — actually *is* consciousness”.

According to the neuroscientist Giulio Tononi, the mathematical measure of that integrated information (in a system) is symbolised by φ (phi).

It can be presumed that many people (at least the ones who think about this issue) would claim that consciousness (to use a metaphor) contains information. That is, a conscious state has (or it instantiates) informational content. However, is consciousness itself information?…

An integrated information theorist may now simply ask:

What is this consciousness which contains information?

Alternatively:

If you take the informational content of consciousness away, then what are you left with?

As just stated, IIT is an identity theory that postulates a literal identity between consciousness and integrated information…

But not so quick!

Giulio Tononi actually believes that consciousness doesn’t equal just any kind of information. However, any kind of information (embodied in a system) may be conscious — at least to some degree.

Of course, we need to know what information actually is…

But, for now, we still can’t simply say that

consciousness = information

Instead, we must say:

consciousness = integrated information

Anil Seth himself makes it clear that integrated information theorists are identity theorists when it comes to consciousness and integrated information.

For example, Seth claims that such theorists treat consciousness “like temperature”, which is “mean molecular kinetic energy”. Thus:

temperature = mean molecular kinetic energy

is syntactically similar to

consciousness = integrated information

Seth doesn’t accept the second identity above. However, he does see the theoretical and experimental importance of information and integration in consciousness studies. He simply doesn’t see their joint instantiation as being equal to, or identical with, consciousness.

Anil Seth as an (Old-Style) Identity Theorist?

Anil Seth also refers to the (old?) identity theory in the philosophy of mind. Or at least he does so tangentially and in passing.

Seth does so when discussing his “preferred philosophical position”, which is “physicalism”. Seth writes:

“This is the idea that the universe is made of physical stuff, and that conscious states are either identical to, or somehow emerge from, particular arrangements of this physical stuff.”

So, according to Seth, physicalists can be identity theorists, or they can embrace emergence (i.e., and still be physicalists).

In detail.

In a video debate with Donald Hoffman (see here), Seth also stresses his newfound interest in emergence and top-down causation. This hints at the fact that he actually opts for the “emerge from” (i.e., rather than the “identical to”) option when it comes to the relation between consciousness and physical stuff. (Can emergent features themselves be identical with physical stuff?)

So Seth not only discusses the literal identity of consciousness and integrated information (which he doesn’t accept), he also hints at his own identity between “conscious experiences” and “neural mechanisms”. He writes:

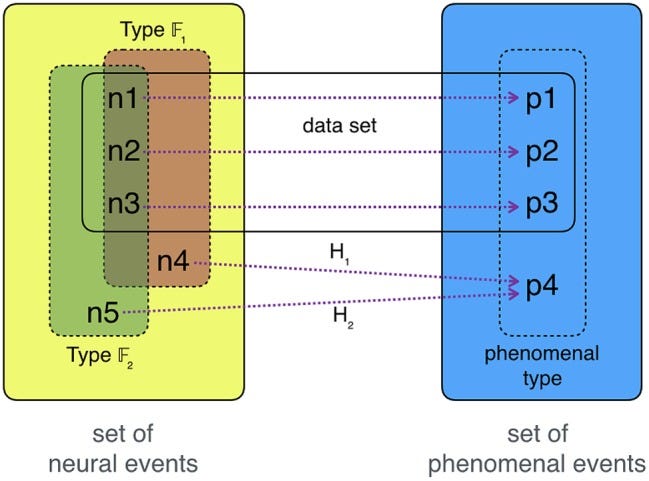

“They key move made by Tononi and Edelman was to propose that if every conscious experience is both informative and unified at the level of phenomenology, *then the neural mechanisms underlying conscious experience should also exhibit both these properties*.”

“That it is in virtue of expressing both of these properties that neural mechanisms do not merely correlate with, but actually account for, core phenomenological features of every conscious experience.”

What are readers to make of Seth’s claim that “neural mechanisms do not merely correlate with, but actually account for, core phenomenological features of every conscious experience”?

Arguably, this isn’t an explicit expression of an identity relation between conscious experiences and neural mechanisms. After all, Seth does use the words “account for”. Thus, those who stress the neural mechanisms which “correlate” with the “phenomenological features of every conscious experience” also say that the former account for the latter.

So is Seth also arguing that these neural mechanisms actually are the phenomenological features of every conscious experience? In other words, are the latter identical to the former?

That said, there are various grammatical phrases which Seth uses which point to the fact that he believes that his own position is not an identity theory… of any kind.

For example, take Seth’s words “neural basis” (i.e., as found in the clause “they made claims about the neural basis of every conscious experience”). Thus, if x is the basis of y, then x and y can’t be one and the same thing. (Seth’s words “underlying mechanisms” may also rule out an explicit identity.)

Giulio Tononi on Integrated Information

We can cite Giulio Tononi again as an example of someone who believes that consciousness (or experience) simply is integrated information. Or, perhaps more accurately, he believes that consciousness is information as it’s processed and integrated by brains and, perhaps, non-biological systems.

Thus, if that’s a statement of identity, then can we invert it and say this? -

information = consciousness

As stated earlier, Tononi actually believes that consciousness doesn’t equal just any kind of information. However, any kind of information (embodied in a system) may be conscious — at least to some degree.

Technically, not only are systems more than their combined parts: those systems have varying degrees of “informational integration”. Thus, the higher the informational integration, the more likely that system will be conscious.

Mere Correlations!

Anil Seth is certainly unsatisfied by (as the popular phrase has it) “mere correlations”. Or, at the very least, he wants to offer his readers more than that. He writes:

“The deeper problem is that *correlations* are not *explanations*. We all know that mere correlation does not establish causation, but it is also true that correlation falls short of explanation.”

Instead, Seth wants something that will close the “explanatory gap between the physical and the phenomenal”.

But does all that mean that Seth is — again — offering us identities?

Seth continues:

“But if we instead move beyond establishing correlations to discover explanations that connect properties of neural mechanisms to properties of subjective experience…, then this gap will narrow and might even disappear entirely.”

The philosopher David Chalmers tackled this issue many years ago (i.e., in 1995). Indeed, he even christened it with a new technical name: “structural coherence”. Chalmers himself wrote:

“This is a principle of coherence between the *structure of consciousness* and the *structure of awareness*.”

Yet, later, Chalmers also notes the problems here:

“This principle reflects the central fact even though cognitive processes do not conceptually entail facts about conscious experience [and] not all properties of experience are structural properties.”

It also needs to be stressed that Chalmers was noting structural coherences between conscious states and what he calls the “structure of awareness”, not between Seth’s “subjective experience” and “neural mechanisms”.

Despite those differences, we can say that if x is coherent with y, then x and y still can’t be one and the same thing. Thus, again, we don’t have any literal identities here.