Contents:

i) Do Rocks Have Minds?

ii) Rudy Rucker’s Scepticism?

iii) A Rock’s Experiences and Sensations

iv) Does Everything Embody Computations?

v) Hive (Group) Minds

vi) Everything is x

vii) The Politics and Spirituality of Panpsychism

viii) Rucker’s Nine-Step Argument

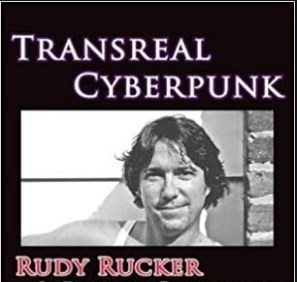

The word “extreme” is used in the title above. As far as I can remember, I’ve never used that word (i.e., in my articles) about any philosophical position before. However, in Ruder Rucker’s case, I believe that the word extreme is perfectly apt. Having said that, I may well be barking up the wrong tree here anyway. Perhaps many of Rucker’s claims aren’t meant to be taken literally. Perhaps they’re meant to be taken poetically, metaphorically or even spiritually. (See the later section: ‘The Politics and Spirituality of Panpsychism’.) Indeed there’s also the oft-used phrase “there are many ways of knowing” — so perhaps Rucker’s way of knowing is different to my own way of knowing. In addition to all that, it’s of course the case that some people will be keen to point out (if not in these precise words) that one person’s absurd position is another person’s commonsensical position.

In any case, it can be argued that Rudy Rucker doesn’t do his fellow panpsychists (see panpsychism) any favours. Or, at the very least, he doesn’t do the more philosophically rigorous and less flamboyant panpsychists any favours.

Rucker has been a professor of mathematics and written non-fiction books on scientific subjects. In terms of detail, Rucker taught mathematics at the State University of New York at Geneseo from 1972 to 1978. He then taught maths at the Ruprecht Karl University of Heidelberg from 1978 to 1980. After that, in 1986, Rucker became a computer science professor at San José State University. (He retired from that job in 2004.) Having given all these academic details, it’s not as if mathematicians can’t say stupid things simply because they’re mathematicians. And the simple fact is that Rucker’s philosophical theories go way beyond maths and science.

Rucker’s non-fiction books on mathematics and physics include his Geometry, Relativity and the Fourth Dimension and Infinity and the Mind. More relevantly to this piece, he wrote The Lifebox, the Seashell, and the Soul. Rucker is also a novelist who’s written over 20 science fiction (or “cyberpunk”) novels and many other works of fiction.

So even though Rucker’s views will unhelpfully muddy the waters for at least some panpsychists, it may still be helpful to tackle what it is he says.

Do Rocks Have Minds?

|

| Add caption |

In his short essay, ‘Mind is a universally distributed quality’ (which can be found in the book What is Your Dangerous Idea?), Rudy Rucker says that “[e]ach object has a mind”. That is, “[s]tars, hills, chairs, rocks, scraps of paper, flakes of skin, molecules” all have minds.

Rucker isn’t only saying that all these objects have “experiences” or embody what some philosophers call “phenomenal properties”. And he certainly isn’t saying that they only embody “proto-experience” (as David Chalmers and other philosophers have it). No; Rucker uses the word “mind”; as well as the words “experiences” and “sensations”.

So it must now be said that when (some) philosophers talk about “experience” (or “phenomenal properties”), they aren’t necessarily also talking about minds. However, it can of course be argued that experiences and phenomenal properties must surely come (as it were) attached to minds.

So what is a mind?

If Rudy Rucker defines the word “mind” so that it only includes what he calls “inner experiences” and “sensations”, then his use of that word would be — by his own definition — correct.

Perhaps experience does come along with mind in the sense that it’s hard to think of a mind-less experience. However, that may not quite be the case when it comes to phenomenal properties because, prima facie, one can conceive (a word often used when philosophers speculate about these issues) of them as belonging to non-minds; or to, yes, Rucker’s scraps of paper or flakes of skin.

Rudy Rucker’s Scepticism?

Rudy Rucker himself seems to offer us a tiny bit of scepticism towards his own positions on panpsychism when he writes the following:

“Might panpsychism be a distinction without a difference?… What is added by claiming that these aspects of reality are like minds?”

However, Rucker doesn’t mention panpsychism itself in the passage above (i.e., after the first sentence). Instead he mentions “quantum collapse”, “chaotic dynamics” and “universal computation” instead.

It’s also worth saying that elsewhere Rucker doesn’t say that particles, rocks, etc. “are like minds” — as he does at the end of the passage above. He says that “each object has a mind”. So we can still repeat his question:

What’s added by claiming that “these aspects of reality are like minds”?

When Rucker says that particles “are like minds”, what’s added to our notion of a particle by saying that? Indeed when Rucker says that a particle “has a mind”, what’s he actually saying? Well, he’s saying — among other things — that a rock, flake of skin and molecule

1) has “singular inner experiences and sensations”,2) “embodies universal computations”,3) and is “glowing with inner light”.

So isn’t all this simply passing the buck to other words? What do the words “inner experiences” and “sensations” mean in the context of a particle? Indeed what does “universal computation” mean in the context of a flake of skin or a molecule?

A Rock’s Experiences and Sensations

As quoted earlier, Rudy Rucker mentions various attributes of mind. He says that stars, hills, chairs, rocks, scraps of paper, flakes of skin, etc. have “singular inner experiences and sensations”. So what are “inner experiences” and “sensations”? (Are there outer experiences?) Wouldn’t objects need sensory receptors, brains, central nervous systems, etc. in order to have sensations? (Wikipedia defines a sensation as “the body’s detection of external or internal stimulation”.)

One can say that all this depends on what sensations are. Alternatively, perhaps it depends on Rucker’s own definition of the word “sensation”. Indeed has Rucker ever defined the word “sensation” within these contexts? Has he even an implicit (or tacit) definition of that word lodged somewhere deep within his mind? Alternatively, is his use of the word simply poetical, metaphorical or spiritual?

As hinted at a moment ago, can some thing have a sensation of pain without it also being a biological body? We can of course conceive (à la David Chalmers and Philip Goff) of pains occurring in things which aren’t human beings or other animals. So what about in the case of Rucker’s rock or his flakes of skin? In evolutionary terms, why would a flake of skin or even a rock need to feel pain? (Perhaps some objects — or even animals — experience pain for non-evolutionary reasons.)

So what about other sensations? Take sexual pleasure and solving a mathematical puzzle.

The sensation of sexual pleasure is related to biological bodies in both human beings and other animals. Indeed even the sensation of solving a mathematical puzzle will have physical and biological expressions and physical and biological substrates. So I’m having a problem here conceiving of sensations belonging to non-biological entities. Indeed I’m also having a slightly lesser problem conceiving of experiences belonging to non-biological entities.

Does Everything Embody Computations?

Just as Rudy Rucker stretches the words ‘mind’, ‘sensation’ and ‘experience’ to great lengths, so he does the same with the word ‘computation’. For example, Rucker says that “every physical system can be thought of as embodying a computation”.

It can be supposed that if a thing is a “physical system”, then perhaps Rucker’s semantic stretch isn’t as extreme as it may at first seem. That is, a physical system must include some kind of complexity…. Well, yes and no. A particle is certainly complex and can be seen as a physical system. The same is true of Rucker’s flake of skin. Indeed it’s hard to see what isn’t both a system and complex.

In any case, if Rucker has already stretched the meanings of both ‘computation’ and ‘mind’, then what’s to stop him doing the same with the word ‘system’ too? Actually, I have more sympathy with Rucker’s use of the word ‘system’ than with his use of either ‘mind’ or ‘computation’. There’s far more baggage attached to the word ‘mind’ than there is to the word ‘system’.

Rucker even goes on to say that “nonsimple” systems “embody computations”. Thus:

i) Whatever a system/thing (whether complex or simple) is, it will embody computations.ii) And whatever a system/thing is, it will also have a mind; (partly?) because it will also embody computations.

As ever, Rucker is explicit about all this. Just as flakes of skin have minds, so “a single electron may be capable of universal computation”. (At least here he uses the word ‘may’.)

What makes an electron capable of computations is (partly?) due to the fact that it may be “afforded a steady stream of structured input”. What does that mean? An electron is certainly causally affected and influenced by its environment. (Such as by fields, forces, other particles and its anti-particle: the positron.) However, can these causal forces be classed as “input”? Is Rucker committing his easy sin again by stretching words beyond their usual meanings?

The notion of input can be read in two or more ways.

In one loose sense, input can be seen as causal affect on a system or on an entity/thing. Alternatively, we can take the word ‘input’ in the way that Rucker hints/says that we should take it. That is, input is essentially information which is worked upon by a thing (or system) according to its own algorithms. However, usually algorithms are carried out by human beings or written into computer programmes by human beings. Alternatively, information can be registered and then worked upon by human mind-brains.

Hive (Group) Minds

Rudy Rucker says that that the

“world’s physical structures break the undivided cosmic mind into myriad of small minds, one in each object”.

The brain is made up of hundreds of billions of molecules. And, according to Rucker, each molecule within each brain has a mind. Thus Rucker is claiming the following:

i) The Cosmic Mind includes individual human minds.ii) Each individual human mind is dependent on a single brain.iii) Each individual human brain is itself made of hundreds of billions of molecules.iv) Each individual molecule of each individual human brain has its own mind.

Rucker himself says that the human mind is a “hive mind” (or group mind), one which is

“based on the minds of the body’s cells and the minds of the body’s elementary particles”.

Here Rucker is entertaining a problem which Philip Goff, David Chalmers and other philosophers tackle: the problem which he himself calls hive minds. This, in turn, creates the problem of the “summing”, “constitution” or “combination” of (as it were) tiny minds into big minds.

What are the physical-to-mind and mind-to-mind connections between the individual minds (i.e., of neurons, molecules, particles, etc.) which make up the human mind-brain, and the human mind-brain itself? If each thing has its own “inner experiences” and “sensations” (according to Rucker), then how do they sum or combine together to create the inner experiences and sensations of a single human person? More particularly, what are the precise connections between each thing’s (e.g., each molecule, neuron, etc.) sensations and inner experiences and the collective inner experiences and sensations of an individual human person?

Everything is x

As stated, Rudy Rucker says that every thing has a mind, sensations, inner experiences, embodies computations, etc. Thus we may have this often-stated formula:

If every thing is x, then no thing is x.

Actually, this formulation doesn’t always work. For example,

If every thing is made of particles, then no thing is made of particles.

[However, it can be said that quarks, leptons, antiquarks, antileptons, gauge bosons and the Higgs boson aren’t themselves made of particles.]

Despite that, in some cases the formula does seem to work. As with:

i) If every thing has a mind, sensations, embodies computations, etc.,ii) then no thing has a mind, sensations, embodies computations, etc.

The most unproblematic term in the above is computations. Every thing embodying computations is far easier to accept than every thing having a mind or having sensations. Then again, there may still be an argument of this type:

i) If every thing embodies computations (and if we can then move step by step from that conditional axiom/premise — see the end section on Rudy Rucker’s “nine-step argument”),ii) then we will eventually arrive at this proposition: Every thing must also have a mind and therefore sensations.

Nonetheless, isn’t this is little like saying that every thing is an athlete or a piece of chocolate? If you stretch words so widely, then they simply loose their point or linguistic force. And that’s precisely what Rucker does.

If Rucker can say that particles have minds, then can I also say that they have a sense of humour? And if I can’t say that particles have a sense of humour, then why can’t I say that? Tell me an important and substantial difference between saying “particles have senses of humour” and saying “particles have minds”. Of course it can now be said that you need a mind in order to have a sense of humour. (Though most/all of the animals which have minds may not have a sense of humour.) Therefore isn’t it possible or even likely that particles also have a sense of humour?

The Politics and Spirituality of Panpsychism

It seems that environmentalism or ecopolitics may be driving Rudy Rucker’s panpsychist position. That is, perhaps he believes that upholding panpsychism will help the environment or one’s relationship with nature. Rucker himself is explicit about this when he writes:

“If the rocks on my property have minds, I feel more respect for them in their natural state. If I feel myself among friends in the universe.”

This is an ethical conditional. Thus:

i) If rocks have minds,ii) then…

The problem about this is that someone else may say to Rucker:

i) If I could fly,ii) then I’d be able to jump out of this window.

Less rhetorically and more feasibly:

i) If animals felt as much pain as humans, and also had similar emotions,

ii) then we/I would be “among friends”.

The problem is that the last conditional about animals isn’t entirely speculative. Rucker’s claims about rocks, scraps of paper, etc., on the other hand, are entirely speculative. There’s a lot of evidence that animals feel pain and have emotions. There’s no evidence at all that rocks, particles, etc. have minds or experience pain/emotions. So helpful (or constructive) philosophical or ethical conditionals must have at least one foot on the ground otherwise surely they’re a waste of time.

The Afterlife

Rudy Rucker also offers us a “spiritual” conditional when he says:

“If my body will have a mind even after I’m dead, then death matters less to me.”

In a sense, if Rucker’s previous speculations were true, then his position on his mind after his own death would also be true; or at least it could possibly be true. Thus all this depends on the Rucker’s conjectures on panpsychism being true.

As as I said about Rucker’s panpsychist environmentalism, this may not matter to him. Thus this is a reactive conditional to Rucker’s stance:

i) If Rudy Rucker’s panpsychism is all about his own emotional well-being (as well as about having a “positive attitude” — as it’s often put — to one’s environment),

ii) then it may not matter if panpsychism is actually true.

What may matter to Rucker are the personal and even collective results of believing — or even claiming — that panpsychism is true. So here’s another conditional:

i) If the consequences of believing in panpsychism are deemed to be positive,ii) then perhaps the truth of panpsychism doesn’t matter.

After all, this ethical and epistemological stance has often been noted when philosophers (such as the American philosopher William James) have talked about the “efficacy of religion”. (As Sam Harris now talks about the efficacy of spirituality.) This has also been seen to be the stance of the “late Wittgenstein”; at least on certain readings. (Yet the man himself hardly wrote a word on the issue.)

However, this fast and loose attitude to truth would surely create a philosophical, scientific and ethical free-for-all if everyone adopted it. (Who knows, perhaps there are — relativistic? — arguments which state that this would be a good thing too.) After all, I could believe that Rudy Rucker is a rock in order to bring it about that no one will take his views seriously. I could also believe that the Welsh are lizards in order to bring forward all sorts of political policies against them.

So why give Rudy Rucker free rein and not other people with similar absurd views? Some people may do so simply because they like — or empathise with — Rucker’s panpsychist philosophy. Is that a good enough reason? Some other people may also like my view that Rucker is a rock or that “the alien lizards rule the world”.

*********************************

Rudy Rucker’s Nine-step Argument

1) Universal Automatism. Every physical entity is a computation.2) Moreover, every physical entity is a gnarly computation.3) Wolfram’s Principle of Computational Equivalence. Every naturally occurring gnarly computation is a universal computation.4) Consciousness = Universal Computation + Self-Reflection.5) Any complex system can be regarded as having self-reflection.6) Panpsychism. Therefore every physical entity is conscious.7) Walker’s Thesis. Life = Universal Computation + Memory.8) Every physical entity has memory via its interactions with the universe.9) Hylozoism. Therefore every physical object is alive.Q.E.D.

Rudy Rucker offers us what he calls a “nine-step argument” (as stated in his ‘A Formal Proof of Panpsychism and Hylozoism’) not only for panpsychism, but also for what’s called hylozoism — the idea that “everything is alive”.

Like many bad arguments, Rucker’s nine-step argument works at a prima facie level. But only at that level. It fails for the same reason that other similar arguments fail. It fails because the (technical) terms included in each step of the argument are either never defined; or, if they are, they’re philosophically speculative or just absurd. Thus if we accept the terms as they stand, then Rucker’s argument has the appearance of being an argument; and even, to some extent, a convincing one. Yet it’s philosophically and logically problematic from the start.

More specifically, if we take each premise as being true, then what follows may well follow. In addition, the whole nine-step argument appears to work at this superficial level too — and for the same reason.

Yet the problems start with premise 1), which is treated as an axiom. Namely,

1) Universal Automatism. Every physical entity is a computation.

Now if we accept 1), all sorts of things will indeed follow from it. And, as with mathematical or geometric systems which have non-proven/non-demonstrated or sometimes even arbitrary axioms (axioms, by definition, have this non-argued-for status), all sorts of things will “logically follow” from those axioms. So let’s take each premise at a time. Firstly 1) again:

1) Universal Automatism. Every physical entity is a computation.

Elsewhere Rucker says that entities “embody computations”. Here he says that “every physical entity is a computation”. That statement hardly makes sense. No physical entity can be a computation (though an abstract entity can). Although the word ‘computation’ is a noun; to compute is something that people, systems or things do. It isn’t what they are.

2) Moreover, every physical entity is a gnarly computation.

The addition of the adjective “gnarly” doesn’t solve our problems or even add anything to Rucker’s argument. It may be an important factor in Rucker’s philosophy of panpsychism; though in the argument it adds very little.

3) Every naturally occurring gnarly computation is a universal computation.

This simply begs many questions which are tackled elsewhere.

4) Consciousness = Universal Computation + Self-Reflection.

Consciousness needn’t come along with “self-reflection” or even with a self. This acceptance of self-reflection is a very big addition. Yet within the nine-step argument itself it’s taken as a given. So what’s behind this addition of self-reflection? Since Rucker has switched from talk of “minds” to talk of “consciousness”, can we now say that if he believes that rocks, particles, scraps of paper, etc. have minds, then he must also believe that they also have consciousness and indeed indulge in self-reflection?

5) Any complex system can be regarded as having self-reflection.

Can it? Why? Rucker’s argument only works on the massive assumption that this claim — among many others — is true.

6) Panpsychism. Therefore every physical entity is conscious.

The other thing about Rucker’s nine-step argument (other than its lack of definitions and its philosophical absurdities) is that there are very weak logical links between each premise. For example, Rucker claims that

6) Every physical entity is conscious.

follows from

5) Any complex system can be regarded as having self-reflection.

The above is a conditional embedded within Rucker’s overall nine-step argument. It works like this:

i) If every complex physical system can be regarded as having self-reflection,ii) then every complex physical system must also be conscious. [Elsewhere Rucker also includes “nonsimple systems”.]

Put is this bare form, the above seems to work. That is, self-reflection seems to imply (or even entail) consciousness. That is, surely you can’t have self-reflection without consciousness.

7) Life = Universal Computation + Memory.

Here we have another addition: memory. As I said about self-reflection, memory needn’t come along with consciousness; though perhaps it must come along with mind. Actually, self-reflection usually comes along with human or animal minds. Thus, as ever, Rucker is applying things which should only be applied to human minds (or human consciousness) to all entities or “systems”.

Indeed that’s Rucker’s whole point.

Not only is Rucker attempting to show that all things have minds (or consciousness), he’s also attempting to show us that all things have human-like minds (or human-like consciousness). Or, at the least, he’s attempting to show us that the minds of rocks, particles, scraps of paper, etc. have self-reflection, memory, inner experiences and sensations — just like us! Thus he’s going way beyond more subtle and more modest forms of panpsychism here. He’s essentially heading towards pantheism or even animism. Thus it’s not a surprise that Rucker ends with this:

9) Therefore every physical object is alive.

Here again there’s a certain kind of logicality of consistency. Again, if entities have minds or consciousness, then they must also be alive; just as most human minds also have self-reflection and memory.

8) Every physical entity has memory via its interactions with the universe.

Again, if all the premises were true (as well as if we don’t question the concepts and words contained in the premises), then 8) seems to follow from the proceeding premises. But that’s no better than saying that the conclusion “Mountains can fly” is true and logically legitimate simply because we’ve constructed a set of bogus premises which artificially lead up to that conclusion. That is, if we take such premises as true, then “Mountains can fly” would indeed follow.

9) Therefore every physical object is alive.

Ditto.