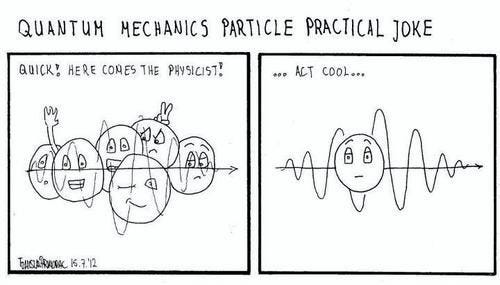

Two simple things pose a problem for anyone wanting to embrace ontic structural realism: 1) The various two-slit experiments. 2) Problems with terminology.

A photon (for example) is a single quantum of light. In fact it's referred to as a "light quantum" or as a “light particle”. It's also the case that single particles have been fired (in double-slit experiments) at relatively long intervals between each firing!

In terms of detail, let's forget here when particles-in-the-plural have been fired (e.g., by J.J. Thomson, Ernest Rutherford, Ernest Walton, etc.) and concentrate on the firing of single particles.

Take Pier Giorgio Merli, Giulio Pozzi and Gianfranco Missiroli who did so in the 1970s in order to demonstrate what's called “interference”. And, in 1989, Akira Tonomura and his colleagues also fired electrons one at a time at the Hitachi research laboratories. Then Herman Batelaan and his team did the same thing and the results were published in 2013.

However, were single particles really fired in these experiments?

Of course something must be fired.

Though is it the case that some individual thing is fired each time? Perhaps, instead, only spatiotemporal chunks (or spatiotemporal slices) of fields are fired. What can't be fired, however, are what philosophers call “individuals”, as we shall now see.

The word “thing” is an everyday word. It can applied to anything (or to any thing). The word “individual” (as used by James Ladyman and other philosophers) is a philosophical technical term. And, finally, the word “particle” is mainly used within a scientific context. (It's true that Isaac Newton's use of of the word “particle” is at odds with many 20th-century uses; though all such uses are still fundamentally scientific.)

Particles (such as electrons) can't be individuals (as most philosophers see individuals) simply because all the particles of a specific kind share all their properties (i.e., spin, mass, charge, etc.). So, semantically, these properties can't be seen as intrinsic or essential because particles don't actually have contingent properties. However, that's unless we bring in the relations which particles have with other things/particles or with fields! And this is where ontic structural realism comes in.

Thus, on a philosophical reading, particles - by definition - can't be individuals. Every particle of a given kind has the same properties – that's if, again, we rule out relational or spatial properties. A single particle, then, isn't like a single human person, who can easily be distinguished from other human persons. Indeed a single human person may well have both essential and contingent properties. (That will depend on one's metaphysical position.)

So if a particle can't be an individual, can't it still be a thing?

Finally, the words “particle” and “electron” are scientific terms. That must surely mean that if physicists say that “electrons are particles”, then electrons are particles. Full stop. Thus since the word “particle” is seen by both laypersons and scientists as a technical scientific term, then naturalist philosophers shouldn't encroach on the territory of physicists by questioning their usage.

Ladyman and Ross stress the fact that modern logic (from Leibniz onward) has been fixated on “individual objects”. However, it may turn out that it's Ladyman and Ross who're fixated on individual objects.

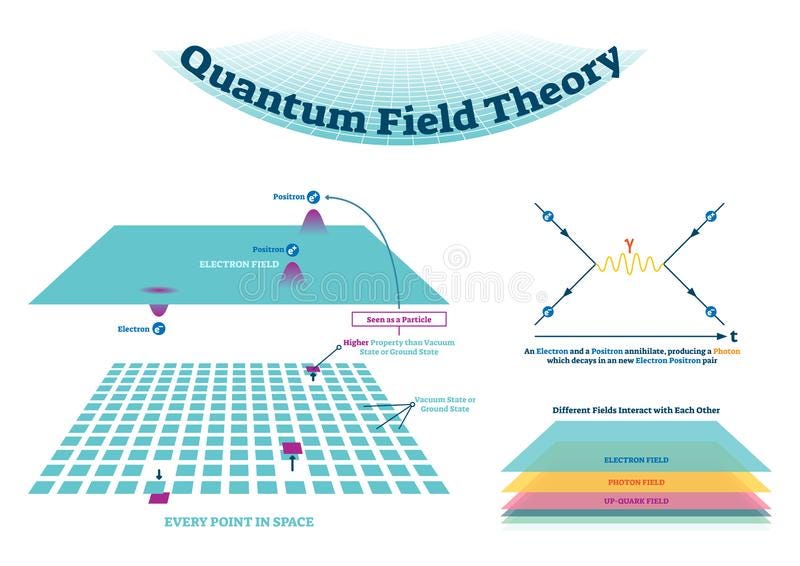

That's a classic question of western metaphysics and it's been asked for over two thousand years. In both quantum mechanics and ontic structural realism, we're told that fields are fundamental, not particles. More precisely, particles in Quantum Field Theory (QFT) are seen as “excitations” of fields. Thus, to state the obvious, it's particles which are the excitations of fields, not fields which are the excitations of particles.

This makes fields fundamental. Or does it? Perhaps it's a difference which doesn't really make a difference – at least it doesn't to most hands-on physicists. (As the physicist John Polkinghorne once put it: “The average quantum mechanic is no more philosophical than the average motor mechanic.”)

“The ‘world-structure’ just is and exists independently of us and we represent it mathematico-physically via our theories.... the fact that we only know the entities of physics in mathematical terms need not mean that they are actually mathematical entities.”

Here we need to know what's meant (philosophically meant) by the word “represent”. That is, what is the ontological (i.e., not representational) relation between structures and the “entities of physics”?

So it's helpful (if only in a limited sense) that Ladyman and Ross explicitly state that they aren't eliminativists about physical entities when they say that

“the fact that we only know the entities of physics in mathematical terms need not mean that they are actually mathematical entities”.

So how does that admission (if it is an admission) help us? Nothing is said about physical entities. Indeed Ladyman and Ross more or less say (in a Kantian manner) that nothing can be said about physical entities (i.e., other than what's said via the medium of mathematical structures). Perhaps, then, we should bite the bullet and accept this limitation if there's no way around it.

“What makes the structure physical and not mathematical? That is a question that we refuse to answer. In our view, there is nothing more to be said about this that doesn't amount to empty words and venture beyond what the PNC allows. The 'world-structure' just is and exists independently of us and we represent it mathematico-physically via our theories.”

So whereas Platonists would be explicit and say it's all mathematics, Ladyman and Ross say that questions about their mathematical structuralism are “question[s] [they] refuse to answer”. Indeed they don't want to indulge in “empty words” in doing so. Ladyman and Ross are quite happy to express their Platonic and (structural) realist position by saying that the

“'world-structure' just is and [it] exists independently of us and we represent it mathematico-physically via our theories”.

Despite all that, the abstract and mathematical scheme of Ladyman and Ross does eventually give way to the physical (on concrete) when they say that the mathematical structures they endorse are “physically realized” and that the predicates they use are (as it were) attached to entities.

Thus this raises the question as to whether or not Ladyman and Ross are only realists about mathematical structures; or whether they're also realists about things - if via the route of mathematical structures. After all,

i) If Ladyman and Ross say that mathematical structures represent “real patterns”,

ii) then surely they can't also be saying saying that mathematical structures represent mathematical structures.

What's more:

i) If mathematical structure x represents a real pattern y,

ii) and this real pattern y represents a physical (or concrete) z,

iii) then mathematical structure x must also represent a physical (or concrete) z.

Structures: Syntax and Semantics

We can say that it's the mathematical syntax of scientific theories which is passed on - not their semantics. That is, we have a possible (or actual) structural continuity; though that only takes the form of mathematical equations.

What's more, in physics the same equations can be mapped onto (or they can model) what are taken to be different physical phenomena. This is the inverse of the “underdetermination of theory by evidence”; in which the same evidence/observations (or the same physical phenomena) can give rise to different theories.