[I also used the following short biographical introduction for my essay ‘Murray Gell-Mann on Complexity’.]

The physicist Murray Gell-Mann was born in 1929 and died in 2019.

In 1964 Gell-Mann postulated the existence of quarks. (The name was coined by Gell-Mann himself and it’s a reference to the novel Finnegans Wake, by James Joyce.) Quarks, antiquarks and gluons were seen to be the underlying elementary elements of neutrons and protons (as well as other hadrons). Gell-Mann was then awarded a Nobel Prize in Physics in 1969 for his contributions and discoveries in the classification of elementary particles at the level of the nucleus.

More relevantly to this piece. In 1984 Gell-Mann was one of several co-founders of the Santa Fe Institute — a research institute in New Mexico. Its job is to study complex systems and advance the cause of interdisciplinary studies of complexity theory.

Gell-Mann wrote a popular science book about physics and complexity science, The Quark and the Jaguar: Adventures in the Simple and the Complex, in 1994. Many of the quotes in this essay come from that book.

Reductionism

Reduction in science has been vitally important. It has sustained and advanced science since the 19th century — if not long before that.

The question is whether or not science is all about reduction. In simple terms. If reductionists (let’s not take that as a scare-word) say that science is “all about reduction”, then there’s a problem. If reductionists don’t say that, then there isn’t problem.

Many individual scientific reductions may be largely correct. Still (as we’ll see Murray Gell-Mann argue later), reduction itself could never be the whole story. (Even that can be deemed a generalisation!) First of all:

1) It depends on what exactly is being reduced.

2) It depends on what is being said about what’s being reduced.

3) It also depends on what a given phenomenon is being reduced to.

In the end, the reductionist’s claim may not be as monumental and all-encompassing as one first imagines. Indeed it’s often people’s gut reactions to some kinds of reductionism (rather than the claims of reductionists themselves) which overstretch things

That said, most people are happy with some — or even many — reductions in science. This is primarily the case because such reductions don’t seem to have any direct impact on people or society; either philosophically, morally/religiously or politically.

Murray Gell-Mann himself focuses in on this debate (in this case) not by talking about reductionism; but by stressing the interplay between “simplicity” and “complexity”. He wrote:

“It is important, in my opinion, for the name to connect with both simplicity and complexity. What is most exciting about our work is that it illuminates the chain of connections between, on the one hand, the simple underlying laws that govern the behavior of all matter in the universe and, on the other hand, the complex fabric that we see around us, exhibiting diversity, individuality, and evolution. The interplay between simplicity and complexity is the heart of our subject.”

Yet it’s hard to say if Gell-Mann endorses or castigates reductionism in the words above because — again — it entirely depends on how people define that word.

For a start, have many — or any — reductionists ever actually claimed that literally everything can be said and explained at the reduced level?

No; usually reductionists have simply said that most things can be reduced to another level. And that’s not the same thing.

In any case, reductions have been vitally important in many sciences (as already stated) and they’ve come up with many important results. Nonetheless, it doesn’t follow from this that all forms of reduction have no room for what’s often called “higher-level descriptions”. The philosopher Patricia Churchland (1943-), for example, says that

“research techniques reveal structural organisation at many strata: the biochemical level; then the level of the membrane, the single cell, and the circuit; and perhaps yet other levels, such as brain subsystems, brain systems, brain maps, and the whole central nervous system”.

Gell-Mann on Reduction & Reductionism

Where there’s reduction, there’s also that which is classed as “fundamental”. In other words, any given phenomenon (whatever it may be) can be reduced to its fundamental components (whatever they may be). Nonetheless, the word “fundamental” seems to be much more philosophical in timbre than merely saying that the physics explains (or even entails) some higher-level phenomena. It’s almost as if the word “fundamental” is normative, rather than descriptive.

Murray Gell-Mann himself gives an explicit characterisation of the word “fundamental” as it’s used in physics. He writes:

“I suggest that science A is more fundamental than science B when

1. The laws of science A encompass in principle the phenomena and the laws of science B.

2. The laws of science A are more general than those of science B (that is, those of science B are valid under more special conditions than are those of science A).”

The problem with the quote above are the two words “in principle”. They make all the difference. (They’re also used a few times in this piece; as well as by Gell-Mann himself.) In basic terms:

What we can know “in principle” = what we can know if we had complete (or total) access to all the information/data/evidence/etc.

That is:

i) B can fully accounted for (or explained) by A if A contains all the information/data/ evidence/etc. about B.

ii) If not, then there can be no complete or total account.

We can tackle the notion of such fundamentality in relation to what Gell-Mann said about quantum electrodynamics (QED).

Gell-Mann tell us that “QED meets the two criteria for being considered more fundamental than chemistry”. What’s more, the “laws of chemistry can in principle be derived from QED”. Thus:

i) If QED is “more fundamental than chemistry”,

ii) then it may follow that chemistry can be reduced to QED.

Gell-Mann goes further and says that

“of course the basic laws of physics are fundamental in the sense that all the other laws are built on them”.

However, he then qualifies this by saying

“that doesn’t mean you can derive all the other laws from the laws of physics, because you have to add in all the special features of the world that come from history and that underlie the other sciences”.

So, in a strong sense, reduction could be possible in the same sense that Laplace’s demon could predict the future state of the world from what he knows about the world today… at least in principle.

Then Gell-Mann qualifies the status of physics and chemistry (or at least parts thereof). Thus:

“Physics and chemistry stem from the fundamental laws, although even there, in the complicated branches of physics and chemistry, the formulation of the appropriate questions involves a great deal of special additional information about particular conditions that don’t obtain everywhere in the universe.”

Here again:

B stemming from the fundamental laws of A doesn’t mean that B is identical to A or vice versa.

Nor does it mean:

A tells us everything we need to know about B.

It simply means:

A underpins (or physically entails) B.

But the reality of A, and even its entailment of B, doesn’t mean that we only need A and can therefore reduce B entirely to A.

Additionally, even if A underpins — or entails — B, that doesn’t mean that B can’t have features, qualities or even laws which are (somewhat) independent of A. Or, as Gell-Mann put it, we need to factor in

“a great deal of special additional information about particular conditions that don’t obtain everywhere in the universe”.

All that gives B an important and relevant independence from A.

(We’ll see later than Gell-Mann’s words above can be applied to condensed matter physics.)

Good Reductionism

Gell-Mann himself explains what reductionism is. He writes:

“The process of explaining the higher level in terms of the lower is often called ‘reduction’.”

Of course if those words are taken literally, then there’s no explicit commitment to reduction — let alone to reductionism. (This is a little unfair because one can’t use the word to be defined in the definition itself.) After all,

i) If we’re “explaining the higher level in terms of the lower level”,

ii) then that doesn’t itself mean that the higher level is being reduced to the lower level.

And it certainly doesn’t imply a commitment to (hard) reductionism. That is, what’s being stated isn’t that the higher level can be reduced to lower level without remainder. Indeed, because of the word “explaining”, we can say that this is a partly epistemic enterprise, rather than a purely scientific or ontological one.

To put this as simply as possible:

Does scientific explanation necessary entail reduction?

Gell-Mann then goes on to tell us why reduction is a thoroughly scientific phenomenon:

“I know of no serious scientist who believes that there are special chemical forces that do not arise from underlying physical forces. Although some chemists might not like to put it this way, the upshot is that chemistry is in principle derivable from elementary particle physics.”

In fact we can go so far as to say that if some “special chemical forces” occurred which weren’t dependent on “underlying physical forces”, then we wouldn’t really be justified in calling them chemical forces at all. The fact that chemistry is derived from, dependent upon, or entailed by physics is built into the discipline of chemistry itself. Thus if anything chemical (as it were) runs free of the physics, then we can question its status as chemistry in the first place.

Now here comes a confession that most (or even all) physicists and chemists must admit to:

“In that sense, we are all reductionists, at least as far as chemistry and physics are concerned.”

Indeed it would be hard to see how things would work in science (or at least in physics) if reductions weren’t employed. Speaking Platonically, reduction seems to be the very essence of physics (if not also of some other sciences).

Elsewhere Gell-Mann again admits to being a reductionist. (In this case, in relation to the status of the “mental”.) He wrote:

“Here again, it must be a rare contemporary scientist who believes that there exist special ‘mental forces’ that are not biological, and ultimately physicochemical, in nature. Again, virtually all of us are, in this sense, reductionists.”

Gell-Mann was also well aware that he’d used the scare-word “reductionist”. So he continued:

“Yet in connection with such subjects as psychology (and sometimes biology), one hears the word ‘reductionist’ hurled as an epithet, even among scientists. (For example, the California Institute of Technology, where I have been a professor for almost forty years, is often derided as reductionist; in fact I may have used the term myself in deploring what l regard as certain shortcomings of our Institute.)”

Thus a scientist can fully accept the autonomy of all (or most) scientific disciplines and yet still be a reductionist. (There’s certainly no contradiction here.) Gell-Mann (sort of) puts this position when he says that

“human psychology — while no doubt derivable in principle from neurophysiology, the endocrinology of neurotransmitters, and so forth) — is also worth studying at its own level”.

In that simple case, reduction simply doesn’t serve much of a purpose. It could be done (at least “in principle”). However, that wouldn’t necessarily get us very far.

Bad Reductionism

Gell-Mann explicitly put the bad-reductionist position of his own faculty (i.e., the California Institute of Technology) at that time. He wrote:

“If a subject is considered too descriptive and phenomenological, not yet having reached the stage where mechanisms can be studied, our faculty regards it as insufficiently ‘scientific’.”

Gell-Mann’s way of distinguishing the non-scientific is very interesting and very particular. Firstly, he sees Real Science as being primarily about “mechanisms”. (That isn’t giving us much to go on.) As for non-science, it is “phenomenological”. Now that can be a reference to the “what it is like” aspects of the mind or brain (e.g., consciousness or subjectivity) or it could refer to the phenomenological accounts of literally any scientific study. (Such as an account of scientists’ “subjective” interactions with particle accelerators!)

Then Gell-Mann himself cites a specific case of bad reductionism:

“At Caltech, it is mostly the brain that is studied. The mind is neglected, and in some circles even the word is suspect (a friend of mine calls it the M-word). Yet very important psychological research was carried our some years ago at Caltech, particularly the celebrated work of the psychobiologist Roger Sperry and his associates on the mental correlates of the left and right hemispheres of die human brain.”

And elsewhere, Gell-Mann writes:

“In that sense, the founding of the Santa Fe Institute is part of a rebellion against the excesses of reductionism.”

Gell-Mann even hints at the possibility that some contemporary reductionists might have excluded Charles Darwin from their faculties! He wrote that

“[i]f Caltech had existed with those same proclivities in Darwin’s time, would it have invited him to join the faculty?”.

Gell-Mann then went on to explain his reasons for his original question:

“After all, [Darwin] formulated his theory of evolution without many clues to the underlying processes. His writings indicate that if pressed to explain the mechanism of variation, he would probably have opted for something like the incorrect Lamarckian idea.”

So, with reference to the earlier quote from Gell-Mann (in which he said that certain disciplines have “not yet reached the stage where mechanisms can be studied”), can we say that Darwin himself wasn’t concerned with mechanisms? Does that also mean that Darwin’s approach was (as Gell-Mann put it) “phenomenological” and purely “descriptive”? Yet Darwin’s approach was indeed very theoretical. In addition, even though Darwin hadn’t the science to explain the underlying mechanisms, that didn’t mean that he was entirely unconcerned with mechanisms.

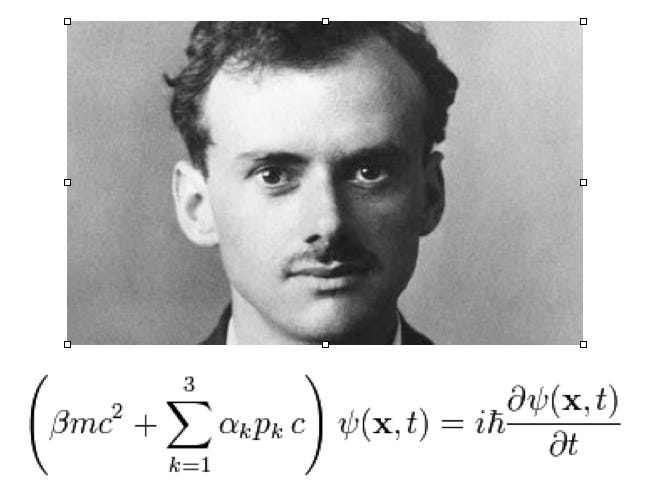

Paul Dirac’s Classic Example of Reduction

In one respect Paul Dirac (1902–1984) put the quintessential (scientific) reductionist position when he stated that his relativistic quantum-mechanical equation for the electron (of 1928) “explained most of physics and the whole of chemistry”. So here we have a kind of meta-reduction in that the whole of physics is being reduced to a yet more fundamental physics.

Of course the interpretation of what Dirac said is entirely dependent on what the word “explained” means. In one sense, what Dirac said was simply a statement of the facts. (Or, at the least, the facts as he saw them.) That is, he presciently realised that

“[a] great many of the phenomena of chemistry are governed largely by the behavior of the electrons as they interact with the nuclei and with one another through electromagnetic effects”.

In that limited sense, then, Dirac was right. However, if we take Dirac to have meant that literally everything about chemistry could by “explained” by his equation (or by physics generally), then he certainly would have been wrong. So it all depends on both what Dirac claimed and what can be deduced from what he claimed. (What’s true of Dirac is also true of other “reductionists”.)

Gell-Mann agreed with Dirac’s grand claim. He wrote:

“QED [quantum electrodynamics] does explain, in principle, a huge amount of chemistry. It is rigorously applicable to those problems in which the heavy nuclei can be approximated as fixed point particles carrying an electric charge.”

Indeed Gell-Mann went further than this. He continued:

“In principle, a theoretical physicist using QED can calculate the behavior of any chemical system in which the detailed internal structure of atomic nuclei is not important.”

Gell-Mann was justifying and explaining some of the (as it were) science of reduction(ism) above. He cited why it is, precisely, that physics can explain “the behaviour of any chemical system”. So this isn’t normative or methodological reductionism: it’s descriptive.

Nonetheless, and surprising as it may seem (to the layperson at least), even condensed matter physics is problematic from the standpoint of reductionism and reduction (as well as emergence). Indeed one definition of the words “condensed matter physics” gives the game away. It states that this field of physics “deals with the macroscopic and microscopic physical properties of matter”. Thus the very fact that macroscopic physical properties are part of the story shows us that condensed matter physics can’t all be about the reduction of macroscopic properties (or “higher levels”) to microscopic properties (or “lower levels”).

As for Gell-Mann, he told us that condensed matter physics “is concerned with systems such as crystals, glasses, and liquids, or superconductors and semiconductors”. More relevantly, condensed matter physics is a

“very special subject, applicable only under the conditions (such as low enough temperature) that permit the existence of the structures that it studies”.

In addition:

“Only when those conditions are specified is condensed matter physics derivable, even in principle, from elementary particle physics.”

Thus, if I’m reading Gell-Mann correctly, condensed matter physics is simply not reducible to “elementary particle physics”.

And since we’re on the subject of condensed matter physics, we must also raise the controversial issue of emergence.

In the case of condensed matter physics again, it can be said that “complex assemblies of particles behave in ways dramatically different from their individual constituents”. One specific example of this is that a range of phenomena related to high-temperature superconductivity are poorly understood; yet the physics of electrons, etc. is understood very well.

Gell-Mann then seemed to strike a middle-way between strong and weak emergence in the following quote. Here’s the hint at strong emergence:

“[I]t’s essential to study biology at its own level, and likewise psychology, the social sciences, history, and so forth, because at each level you identify appropriate laws that apply at that level.”

Then Gell-Mann also hinted at weak emergence:

“Even though in principle those laws can be derived from the level below plus a lot of additional information, the reasonable strategy is to build staircases between levels both from the bottom up (with explanation in terms of mechanisms) and from the top down (with the discovery of important empirical laws). All of these ideas belong to what I call the doctrine of ‘emergence’.”

In conclusion, Gell-Mann wrote:

“Here, much more than in the case of nuclear physics, condensed matter physics, or chemistry, one can see a huge difference between the kind of reduction to the fundamental laws of physics that is possible in principle and the trivial kind that the word ‘reduction’ might call up in the mind of a naive reader. The science of biology is very much more complex than fundamental physics because so many of the regularities of terrestrial biology arise from chance events as well as from the fundamental laws.”

This leads onto Gell-Mann’s interest in complexity; which is the subject of my essay ‘Murray Gell-Mann on Complexity’.