i) Introduction

ii) Value Judgements and Background Assumptions

iii) The Epistemic Evaluation of Scientific Theories

iv) The Political Applications of Scientific Theories

v) Conclusion

Introduction

Elizabeth Secor Anderson is Arthur F. Thurnau Professor and John Dewey Distinguished University Professor of Philosophy and Women’s Studies at the University of Michigan. She has been published by — and featured in — The New Yorker, Jacobin, Chris Hedges’ Truthdig, 3:AM Magazine, Democracy, etc.

This is a commentary on Elizabeth S. Anderson’s paper, ‘Feminist Epistemology: An Interpretation and a defence’. I focus on a single — though important — part of that paper: her account of how (what she calls) “value judgments” and “background assumptions” impinge on (all) scientific theories. More specifically, I focus on Anderson’s account of how political and ideological value judgements and background assumptions do so. That supposition is at the heart of her paper.

Value Judgements and Background Assumptions

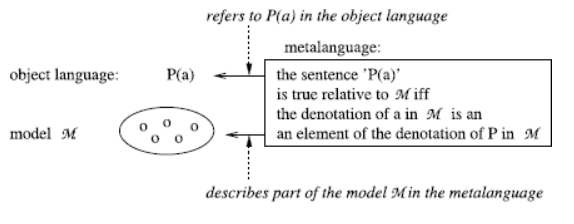

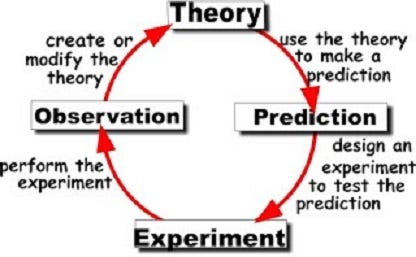

There is indeed a “logical gap” between observation/data/evidence and scientific theory. (In the philosophy of science, this is called the underdetermination of theory by data/evidence.) However, it doesn’t automatically follow that we need necessarily plug that gap with what Elizabeth Anderson calls “value judgements”. Of course this depends on what exactly Anderson means by those two words. Considering the rest of her paper, she doesn’t only mean those judgements as to what makes a scientific theory “simple”, “elegant”, “explanatorily powerful”, or “empirically adequate” (or a mixture of all these, as well as other criteria); which most scientists and philosophers of science accept as determinants of scientific theory. Instead, Anderson is talking about ideological and political value judgements.

We all also need to know what Anderson means by “background assumptions”. These background assumptions would be — or would go alongside — the various value judgments; and those value judgments — or at least some of them — are seen to be be (at least in part) ideological and political in nature. Thus there are various background assumptions which will be “used to argue that a given observation constitutes evidence for a given hypothesis”. Again, need these (or any) background assumptions be political or ideological in nature?

Of course there’ll be a problem with that question, at least according to certain political theorists. And that problem arises from the view that all background assumptions (or value judgments) can’t help but be ideological or political in some — or even in many — ways. Here the political theorist’s argument will be about the necessity of the scientific theorist’s ideological or political background assumptions. However, wouldn’t the political theorist’s belief (about scientific theorists or theories) be a case of arguing in a circle if he/she already accepts the necessity of political or ideological background assumptions impinging on scientific theory-construction? If she/he already believes in that necessity, then she/he is bound to find such ideological or political background assumptions (or value-judgments).

So what if some scientific theorists are anti-political, apolitical or just plain ignorant of politics (many are)? Here again the political theorist will back herself/himself up with the statement that “everyone is political” — even if that person (or scientific theorist) is non-political, apolitical or politically ignorant. The argument will be that such apolitical scientific theorists must accept the given ideologies and political realities of her/his milieu (i.e., simply because she/he doesn’t question them). Likewise, even the politically ignorant must be political or ideological in some kind of way — even if in a rudimentary kind of a way.

The other thing is that we’ll need to know what kind of scientific observations Anderson is talking about. Is she talking about observing the effects of particle interactions in a bubble chamber or the effects of having a low income on a family? You can argue that political or ideological value judgements (or background assumptions) may affect the latter; though what about the former? Indeed in principle — even if only in principle — ideological or political background assumptions needn’t necessarily impinge on one’s scientific observations of a poor family either.

For example, what if we programmed a computer to do that “observing”? What if we used someone from a completely different culture or one who wasn’t poor, rich, powerful or particularly political? (Although, I said earlier, the political theorist will reject that final possibility and probably the former ones too.)

I may not be being entirely fair to Anderson by my pitting bubble-chamber observations with the observations of the effects of a low income on the lifestyle of a family. That’s because Anderson provides her own (more likely) example of how politics or ideology can impinge on scientific research and indeed on scientific observation. She cites the examples of evolutionary theory and work in genetics. Here she finds many examples of politics or ideology intruding on scientific theory. Yet this is evolutionary theory and genetics we’re talking about: both of which clearly and obviously impinge on both the human and the social. Despite that (again): what about observing the effects of particle collisions in cloud chamber or studying the behaviour of ants? (One can indeed “politicise” ant behaviour — in many directions.)

So the problem noted earlier will arise here too: which kind of observations is Anderson talking about? Is she talking about all scientific observations and all scientific theories? Specifically, she says that

“it is not unreasonable to use any of one’s firm beliefs, including beliefs about values, to reason from an observation to a theory”.

Again, what kind of observations is Anderson talking about there? Is she talking about all scientific observations? Indeed which kind of “firm beliefs” and “values” is she talking about? Does she also include and allow beliefs and values which strongly clash with her own? (Parts of Anderson’s paper highlight the problems she has with certain beliefs and values.)

Because the phrase “value judgment” is so vague, it’s initially unobjectionable for Anderson to state that theories which “incorporate value judgements can be scientifically sound as long as they are empirically adequate”. But there’s a problem here too. Is it also a question of value judgements when it comes to deciding what actually makes a theory “empirically adequate” (or elegant, parsimonious, explanatorily powerful, highly predictive, etc.) in the first place? (Now does that work for or against Anderson’s stress on value judgments in science and epistemology?) If data, evidence or observations underdetermine theory (as the philosophical theory has it), then the fact that a theory is empirically adequate, etc. may not amount to much if hiding in the bushes behind that empirical adequacy, etc. are not only value judgments (or background assumptions), but also political or ideological value judgments (or background assumptions). If that’s the case, then surely empirical adequacy, etc. may not amount to much.

In any case, many philosophers of science have argued that empirical adequacy is easy (i.e., because data, evidence or observations always underdetermine theory). If that’s true, then perhaps background assumptions (or value judgments) really do take on an importance which we otherwise didn’t expect. Perhaps empirical adequacy, etc. weigh less on the scales than the prior value (political/ideological) judgments (or background assumptions) which are made and which then impinge on that empirical adequacy, etc. (or on what we believe is empirically adequate, etc.).

The Epistemic Evaluation of Scientific Theories

Anderson says that the logical gap between

“the epistemic evaluation of theories cannot be sharply separated from the interests their applications serve”.

Yes they can… surely? So the argument is that, normatively, it is wrong to ignore such applications. (That too would depend on one’s normative stance on these issues.) Again, this would — or could — be more the case of a normative judgement (or epistemic evaluation) being applied — by the feminist epistemologist — to the otherwise neutral or apolitical epistemic evaluations of scientific theories. What’s being said by Anderson is normative in itself. It’s not a case of saying that scientific theorists indulge in epistemic evaluations which are sometimes (or always?) political or ideological. It’s more a case that Anderson believes that they should indulge in such political evaluations. That is, a scientific theorist can (and often does) separate his theory — and even his epistemic evaluations — form “the interests their applications serve”. Anderson is arguing that she/he shouldn’t do so.

This, then, ends up being less of a project in discovering the value judgements or background assumptions (specifically political and ideological ones) involved in scientific theory-construction, and more a case of a feminist epistemologist saying that the scientific theorist should have a political and ideological attitude towards the political applications of his theories. Not only that. The scientific theorist should have politically/ideologically acceptable (not the true, correct or empirically adequate) attitudes towards the applications of her/his scientific theories. Similarly, this also means that this is also all about scientific theorists having the wrong kind of political and ideological background assumptions and making the wrong kinds of value judgment. That is, it’s not just a case of scientific theorists simply having background assumptions and making value-judgements.

We’ve just crossed over another and wider logical gap: the gap between scientific theory and the outright political and ideological assessments of — or normative judgements upon — those scientific theories.

This account of Anderson’s views is correct because Anderson herself says that it is (i.e., at least indirectly). Anderson argues that feminist naturalised epistemology

“rejects the positivist view that the epistemic merits of theories can be assessed independently of their ideological applications”.

Here again it’s not a case of Anderson — or any other feminist epistemologist — discovering the scientific theorist’s political and ideological positions which impinge on her/his accounts of the “the epistemic merits” of his theories. It’s more a case of Anderson arguing that ideological and political considerations should impinge on her/his accounts of the epistemic merits of his theories. Not only that. It should be ideologically and politically correct considerations which do so.

We’ve moved from discovering — or simply acknowledging — the role and importance of ideology and politics (in the construction of scientific theories) to the view that scientific theorists should be fully ideologically and politically aware all the way through the process of scientific theory-construction. To be more specific, the scientific theorist should always keep his eye firmly fixed on all possible future “political applications” (Anderson’s words) of her/his theories.

The Political Applications of Scientific Theories

We can characterise Anderson’s position by making these three points:

i) Anderson stressed the “logical gap” between observations/data/evidence and the theories which arise from them.

ii) She then noted the logical gap between the “epistemic evaluation of theories” and “the interests their applications serve”.

iii) Finally, Anderson also noted the logical gap between scientific theories and their political applications (which is obviously related to ii) above).

Just as Anderson discerns the possible ideological and political content of scientific theories which aren’t (to many others or the scientific theorists themselves) apparently ideological or political at all; so now she also tackles the political and ideological use of scientific theories.

Specifically, Anderson says that “a theory is [can be] used to support unpopular political programmes”. We’ll of course need to be clear what it means to use a theory; let alone what the words “unpopular political programmes” mean. Nonetheless, Anderson does say that such a use wouldn’t necessarily show us that “the theory is false”. That’s certainly true. Isn’t it the case that, for example, the theories and findings of quantum mechanics were used — directly or indirectly — to build atomic weapons? (In turn, they were then used for blatantly “political programmes” — from the bombing of Hiroshima to sustaining - some may argue - the Cold War.) However, just as my ballpoint pen can be used to stab someone’s eye out (but which can’t be blamed on either the inventor or manufacturers of ballpoint pens), so theories in quantum mechanics — or at least those who thought up the theories — can’t be blamed for Hiroshima or for the Cold War. (The earlier work in quantum mechanics began in the early 1920s: that was some twenty years before there was any research into nuclear weapons —i.e., roughly, in 1940.)

To tackle an example which Anderson herself (see later) cites.

In principle, even if a scientific theory or scientific research states that women are intellectually inferior to men (in whatever way you like — this is a what-if story), that too doesn’t automatically mean that it will be used to support political programmes of female oppression or even be used as a theoretical excuse to force women to stay at home. That possible theory of — or research into - the mental inferiority of women could be true and still not be used for forcing women to stay at home (or for any other discriminatory political or social practice). However, in this case at least, the reality is that any complete separation of theory and political application will be unlikely. That is, such scientific findings, research or theories will indeed be “politicised”. Yet much of that politicisation will be down to those who want to make sure that such findings, research or theories are never politically instantiated. Many political theorists and activists will even argue that such research be discontinued (i.e., because it’s politically or ideologically objectionable).

Thus we firstly have the scientific findings, research or theories, and then we have the politicisation of such things. Nonetheless, Anderson’s argument is that politics and ideology are there from the very beginning — i.e., in the actual findings, research or theories. And if we accept that, then any politicisation which later occurs is only additional to the inherently political nature of science itself.

Anderson cites her own example of a bad political application of a (possibly true?) theory: the case of Professor Steven Goldberg. According to Anderson, he

“uses his theory of sex differences in aggression to justify a gendered division of labour that deliberately confines women to low-prestige occupations”.

As stated earlier, Anderson says that although there may be bad political applications of a scientific theory, that doesn’t necessarily make the theory false. And here too she talks about this further “logical gap”:

“The proponents of the programme [should respect] the logical gap between fact and value.”

However, even if the “facts” are applied (for example) to building nuclear weapons or sexist social policy, that is still — on the surface at least — only an application of the facts. It can still be argued that the value bit of the equation only comes in later on — when it’s directed at the appliers of the theory. (Such as the technologists or the political decision-makers.) It will of course still be argued (by Anderson and others) that scientific theorists should be fully conversant with the political applications of their theories… But should they? This doesn’t seem to be a question of the scientific theorist being burdened down with hidden or unacknowledged values (specifically political and/or ideological values). Rather, it’s really a question of values (specifically political and ideological values) being foisted or imposed upon them by feminist epistemologists, feminist philosophers of science, or even by people directly involved in politics.

This would suggest that all this is actually about the normative and political claim that scientific theorists should be politically and ideologically biased; rather than them actually being politically or ideologically biased (if often in the wrong direction). In other words, at this level (at least) all the ideology and politics is coming from one direction: from the feminist epistemologist (or from the feminist philosopher of science). Thus if scientific theorists don’t know — or care — about the political applications of their theories, then it’s hard to accuse them of using ideological or political value judgments or of having ideological or political background assumptions. All the politicising (or the making of political value judgments) seems to come later: from the feminist epistemologist and from the political appliers of scientific theories. Although (as stated earlier) Anderson (as well as other feminist epistemologists) may argue — and many political theorists do argue this way — that the scientific theorist not caring (or even not knowing) about the political applications of his theories is itself a deeply political and ideological stance.

Conclusion

To sum up.

Professor Elizabeth S. Anderson isn’t simply arguing that political and ideological value judgements and background assumption exist in all scientific theorising. Anderson is also making the political point that there are many politically-incorrect value judgements and background assumptions which underpin scientific theorising. In addition, scientific theories are often applied in ways that (to her at least) are politically objectionable.

This means that Anderson’s paper is just as much a work of politics as it is a work of epistemology (or of philosophy of science). Having said that, if Anderson deems the scientific theory/politics “binary opposition” to be false in the first place (i.e., it’s naive to separate science from politics), then my interpretation is hardly surprising. Indeed, by Anderson’s own lights, she must surely agree (at least in part) with my broad conclusion about her own position.

Finally, if Anderson is correct to argue (if often indirectly) that politics and ideology pervade all scientific theories, and that she additionally argues (again, often indirectly) that such politics and ideology should be politically acceptable (but to whom?), then scientific theory (alongside epistemology and philosophy of science) effectively becomes a political battleground. Despite all that, it’s probably the case that Anderson believes that this possible scientific theory/politics battle has always been the case anyway.

So my broad conclusion is that Anderson advances the position (if somewhat indirectly) that all science is inherently political. (Historically, this was also the position of both the Nazi and Soviet states — see ‘Ideologically Correct Science’.) Thus it follows (to her at least) that epistemologists, philosophers of science and political activists/politicians (or at least those who share her own politics) must make sure that all science is both politically acceptable and politically correct.