Philosopher Craig Callender believes that “many debates in analytic metaphysics are sterile or even empty”. Is he right about this?

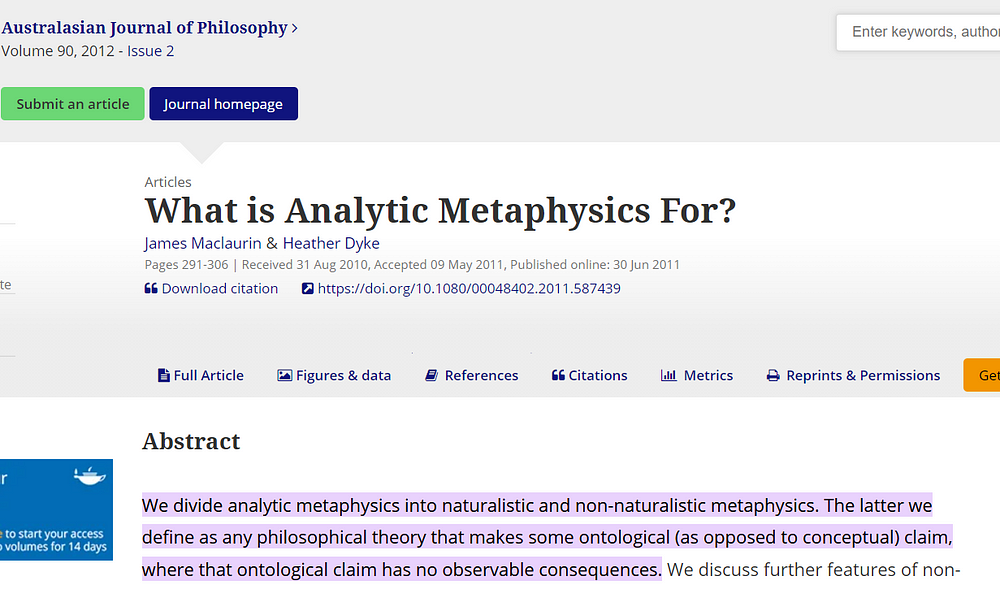

“We divide analytic metaphysics into naturalistic and non-naturalistic metaphysics. The latter we define as any philosophical theory that makes some ontological (as opposed to conceptual) claim, where that ontological claim has no observable consequences. We discuss further features of non-naturalistic metaphysics, including its methodology of appealing to intuition, and we explain the way in which we take it to be discontinuous with science.” -

— — From ‘What is Analytic Metaphysics For?’

According to the philosopher Craig Callender (in his paper ‘Philosophy of Science and Metaphysics’), it’s the case that

“mainstream analytic metaphysics has moved further away from scientific concerns at the same time that philosophy of science has moved closer to science”.

Prima facie, Callender’s position is similar — though obviously not identical — to that expressed by the logical positivists (in the 1930s and 1940s) when it it came to various (or even all!) metaphysical issues and disputes.

Callender continues:

“The reason is that it’s hard to imagine what feature of reality determines whether a fist is a new object or not. How would the world be different if hands arranged fist-like didn’t constitute new objects?”

The begged answer is: No difference whatsoever.

Take also the case of the English philosopher A.J. Ayer (1910–1989) when he was writing about the rival claims of metaphysical pluralism and monism. In his book Language, Truth and Logic, he wrote:

“[T]he assertion that Reality is One, which is characteristic of a monist to make and a pluralist to controvert, is nonsensical, since no empirical situation could have any bearing on its truth.”

Since logical positivists have just been mentioned, it seems clear that Callender is also asking for a kind of positivist answer to his questions. That is, he’s asking if these questions can — at least in part! — be answered by experience. The analytic metaphysician, of course, would say that such “positivist” questions are themselves… well, meaningless. Of course experience (or the empirical) is irrelevant to these questions. Or, at the very least, experience alone can’t answer them. Indeed experience alone couldn’t even answer any of the logical positivists’ questions. And that’s because experience alone can’t answer any question.

Not that all those who have a problem with analytic metaphysics also have a problem with metaphysics when it’s seen more generally.

Not All Metaphysics is Bad

Callender puts the case that one can be against much (or even all) of what’s called analytic metaphysics and yet still not be against metaphysics itself. He states:

“I come at the question simultaneously convinced that many debates in analytic metaphysics are sterile or even empty while also believing that metaphysics is deeply infused within and important to science.”

Moreover, it’s not only that one must accept metaphysics even when one also places science in an — or the — important position. It’s simply that one simply can’t avoid metaphysics — not even in science itself.

Callender continues:

“[W]e have these concepts, ‘metaphysics’ and ‘sciences’. There is no sharp difference between the two. To a rough approximation, we can think of metaphysical claims as more abstract and distantly related to experiment than scientific claims.”

And finally:

“I think that what we conventionally call science in ordinary affairs is inextricably infused with metaphysics from top (theory) to bottom (experiment). If this is right, metaphysics is deeply important to science. Laying bare the metaphysical assumptions of our best theories of the world is a crucial and important part of understanding the world.”

Yet, seemingly, not all analytic metaphysicians ignore science.

Analytic Metaphysics and Science

Take the American philosopher Ted (Theodore) Sider.

Sider claims not to ignore or disparage science. He also sees (much?) analytic metaphysics as being “quasi-scientific”.

In his paper ‘Ontological Realism’, Sider writes:

“[Analytic metaphysicians’] methodology is rather quasi-scientific. They treat competing positions as tentative hypotheses about the world, and assess them with a loose battery of criteria for theory choice. Match with ordinary usage and belief sometimes plays a role in this assessment, but typically not a dominant one. Theoretical insight, considerations of simplicity, integration with other domains (for instance science, logic, and philosophy of language), and so on, play important roles.”

It may also be interesting to mention panpsychism and idealism here.

Panpsychists and idealists (or at least some of them) have the same position as Sider on this aspect of the debate. That is, they see their own isms as being quasi-scientific. For example, analytic metaphysicians stress

“competing positions as tentative hypotheses about the world, and assess them with a loose battery of criteria for theory choice”.

And panpsychists and idealists too emphasise “simplicity”, “integration” and (to use a word often used by panpsychists) “parsimony” (see here).

This isn’t a surprise.

All sorts of unlikely candidates have been seen as being quasi-scientific — or indeed, just plain scientific. To take two obvious examples (i.e., other than idealism and panpsychism): Marxism and Freudianism were — and sometimes still are — seen as being scientific. Indeed the Austrian-American philosopher Paul Feyerabend (1924–1994) even stressed the scientific nature of astrology and voodoo (see here).

For example, in his book, The Trouble With Physics, the theoretical physicist Lee Smolin (when he was discussing what makes something a science with Feyerabend himself) wrote:

“Was it because science has a method? So do witch doctors. Perhaps the difference, I ventured, is that science uses math. And so does astrology, he responded, and he would have explained the various computational systems used by astrologers, if we had let him… Newton had spent more time on alchemy than on physics. Did we think we were better scientists than Kepler or Newton?”

All this means that we need to be careful when philosophers and theorists drop scientific technical terms into their writings. Or, alternatively, we need to be careful when theorists or philosophers include only certain aspects of science; though who, at the very same time, ignore (or reject) what could very well be far more scientifically important or relevant when it comes to the legitimacy of their non-scientific (or strictly philosophical) claims.

So now let’s take a few seemingly extreme positions in analytic metaphysics (or plain metaphysics, for that matter).

Take Peter van Inwagen.

Bizarre Analytic Metaphysics: Craig Callender’s Clenched Fist

The American philosopher Peter van Inwagen (1942-) believes that only elementary particles and living organisms exist. That is, he believes that cups, tables, planets, etc. don’t exist…

In his book Material Beings (1995), Van Inwagen argues that all material objects are either elementary particles or living organisms. (It’s the case that every “composite object” — by definition! — is made up of elementary particles.) Van Inwagen concludes by arguing that tables, chairs, bikes, etc. don’t exist.

We can immediately ask three questions here:

1) Does Peter van Inwagen believe that such …s don’t exist?

2) Does he believe that …s don’t exist qua objects?

3) Is it simply that van Inwagen believes that we have the wrong philosophical conceptions of …s?

Mereological nihilists also believe that only elementary particles (if not also living organisms) exist; or that they’re the only genuine objects.

Mereological universalists, on the other hand, believe that any arbitrary combination of otherwise separate objects can — or do — constitute a further object. (That means that your own left butt cheek and the sun above it can — or do — constitute a single object.)

It’s the nature of these metaphysical beliefs which are often deemed to be “bizarre” and “trivial”. (Can the trivial and bizarre exist side by side?)

And, as already mentioned, Craig Callender (quoting Eli Hirsch) asks the following question:

“[W]hen I bend my fingers into a fist, have I thereby brought a new object into the world, a fist?”

Well, it’s certainly true that something must have changed when Callender bent his fingers into a fist. For a start, his hand changed its shape. So did that change — in and of itself —help constitute or bring about a different (or new) object?…

Does anyone know?

Does it matter?

Does this fist-clenching involve something (as Callender himself puts it) “deep [and] interesting about the structure of mind-independent reality”?

It’s hard to say because it’s difficult to understand the question. And even if the question can be understood, how would we know how to find a determinate (or even any) answer to that question?

We can excuse analytic metaphysicians by saying that this example — or other less bizarre ones — may provide us with the means to establish what an object is; as well as how we can decide that issue.

To repeat. We have a hand… surely that’s an object. Or is it?…

Then that hand has formed a clenched fist.

Is that clenched fist a different object?

If it is a different object, then why is it so?

If it’s the same object with a different shape, then why is it still the same object?

In any case, if we christen a clenched fist as a “new object”, “the same object”, or even “not an object at all”, then what ontological (or plain philosophical) difference would that make? That is, it certainly makes no practical or scientific difference; though is it still metaphysically “deep” or “interesting”? If it is, then exactly why is it deep or interesting?

We may agree with the Australian philosopher David Chalmers (1966-) here and say that this is merely a “verbal” dispute (see here); or a dispute primarily about definitions. That is, we are free to define a clenched fist as a separate object to a hand if we want to. On the other hand, we may decide not to do so.

So how could we decide which definition (or position) is the correct one?

Can we decide that issue — even in principle?

More relevantly, does this issue take us beyond the verbal and tell us something about the “structure of mind-independent reality”?

Indeed forget mind-independent reality:

What does this clenched-fist issue or position tell us about reality — full stop?

A mereological nihilist will (or may) argue that neither the hand nor the clenched fist are objects.

So does this position take us beyond the verbal or definitional? And if it does, then how and why does it do so?

The four-dimensionalist will (or may) argue that the clenched fist is a “temporal part” of the hand.

Again, does this position take us beyond the verbal or definitional?

A mereological universalist will (or may) argue that the clenched fist and the iron glove it comes in together make an object; which also includes the moon above the clenched fist in its iron glove.

So is this position taking us beyond the verbal or definitional?

Indeed if all these positions are essentially about definitions and verbal descriptions; then, arguably, we can conclude that they aren’t genuinely metaphysical positions at all!

Straw Targets?

If Craig Callender hadn’t chosen what can be seen as bizarre and absurd examples, then perhaps we can take such metaphysical positions more seriously.

The question is: Are they simply bizarre and absurd?

Take Callender’s next example.

This example seems even more bizarre and absurd than the one just cited. Callender writes:

“[W]hether a piece of paper with writing on one side by one author and another side by a different author constitutes two letters or one [].”

One’s first reaction to this may be:

I simply can’t be bothered with it! Does it matter? Are there really metaphysical implications to this question? Is it, again, all verbal or definitional?

Nonetheless, one of Callender’s other examples does appear to be a reference to a more (as it were) concrete case. It was originally cited by W.V.O. Quine in his paper ‘Ontological Relativity’ (1968). Callender writes:

“[W]hether rabbit-like distributions of fur and organs (etc.) at a time are rabbits or merely temporal parts of a rabbit.”

Quine — when talking about ontological relativity and the inscrutability of reference — used the example of rabbits in a specific field of vision. Yet this odd scenario was primarily motivated by the issue of interpreting the utterances of aliens — and even people here on earth — who spoke a language the researchers didn’t understand. Thus, in one respect, this isn’t (strictly speaking) a metaphysical issue at all. It’s either an issue in semantics or one in epistemology (perhaps both).