The Unexperienced Soul

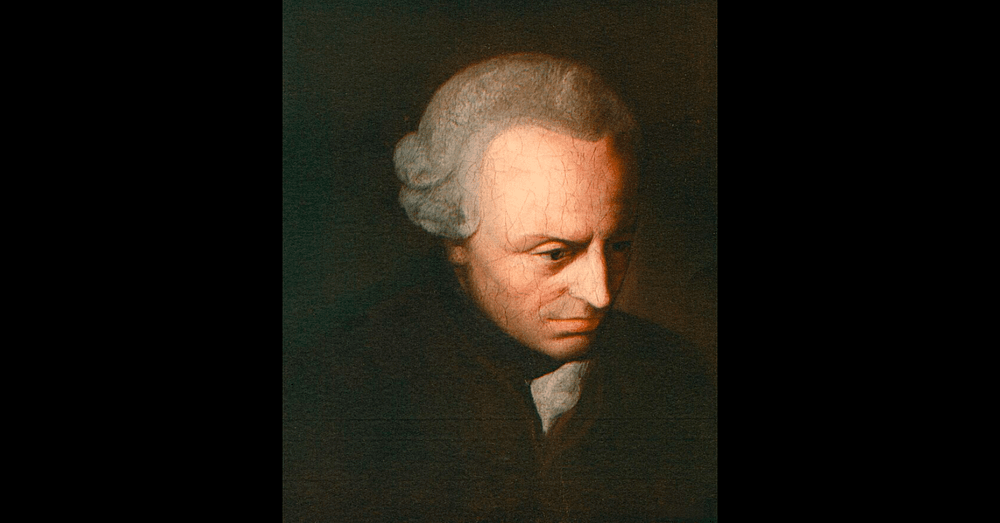

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) was quite at one with David Hume (1711–1776) in that he too believed that we never actually any experience of the self. (In Kant’s own terms, the “soul”, or the “substance of our thinking being”.) This is because the self is the means through which we experience. Thus, it can’t also be an object of experience.

Of course, we can experience the (to use Kant’s own term) “cognitions” of the soul. However, we can’t experience the soul which has (or carries out) the cognitions. Like all other substances, the “substantial itself remains unknown”. We can, however, be aware of “the actuality of the soul” through the “appearances of the internal sense”. This is part of Kant’s defence (though not proof) of the soul.

Again, none of this has anything to do with any actual experience of the soul.

The Unperceived Tree

Immanuel Kant’s following argument is is very much like Bishop (George) Berkeley’s.

According to Kant, when we imagine a unperceived tree, we are, in fact, imagining it as it is perceived — even if supposedly perceived by some kind of disembodied mind. As Kant put it, in such cases we represent “to ourselves that experience actually exists apart from experience or prior to it”. Thus, when we imagine the objects of the senses existing in a ostensibly “self-subsisting” manner, we are, in fact, imagining them as they would be as they are experienced. That isn’t surprising because there’s no other way to imagine the objects of the senses.

Thus, Kant argued that we are not imagining things-in-themselves.

Space and time, on the other hand, are “modes” through which we represent the external objects of the senses. As Bertrand Russell put Kant’s position, we wear spatial and temporal glasses through which we perceive the world. Thus, if we take the glasses off, then, quite simply, space and time would simply disappear. They have no actuality apart from our minds.

Appearances must be given up to us in the containers we call space and time. Space and time are the vehicles of our experiences of the objects of the senses. In a sense, then, it seems like a truism to say that “objects of the senses therefore exist only in experience”. That’s because there are few experiences without the senses, and our senses themselves help determine those experiences.

The Antinomies and Experience

What are the antinomies?

They’re two opposing positions of philosophical dispute which have (to use Kant’s own words) “equally clear, evident, and irresistible proof”. Stated in another way: a proposition and its negation are both equally believable (or acceptable) in terms of rational inquiry.

Kant gives an example of such an argument with two equally weighty sides. One is whether or not the world had a beginning, or whether it has existed for eternity. The other is whether or not “matter is infinitely divisible or consists of simple parts”.

What unites these arguments is that none of them can be solved with the help of experience. In one sense, then, this is an argument about the limits of empiricism. That said, according to the empiricism of, say, the logical positivists, these antimonies were considered to be “meaningless” precisely because they can’t be settled (or solved) by consulting experience.

As Kant himself put it, such “concepts cannot be given in any experience”. To Kant, it followed that such issues (or problems) are transcendent to us.

Kant went into further detail about experience-transcendent (or evidence-transcendent) facts or possibilities.

Through experience, we can’t know whether or not the “world” (i.e., the universe) is infinite or finite in magnitude. Similarly, infinite time can’t “be contained in experience”. Kant also wrote about the intelligibility of talking about space beyond universal space, or time before universal time. If there were a time before time, then it wouldn’t actually be a time before time because time — according to Kant — is continuous. And if there were a space beyond universal space, then it wouldn’t be beyond universal space because there can be no space beyond space itself.

Kant also questioned the validity of the notion of “empty time”. That is, time without space, and time without objects in space. Kant, instead, argued that time, space and objects-in-space are all interconnected.

So perhaps Kant believed (like Leibniz before him) that time wouldn’t pass without objects to (as it were) measure the “movement” (through disintegration and growth) of time. Similarly, on Kant’s cosmology, space without time would be nonsensical.

Freedom and Causal Necessity

“[I]f natural necessity is referred merely to appearances and freedom merely to things in themselves [].”

This position (again) unites Kant with Hume, who also believed that necessity is something that we (as it were) impose on the world.

Necessity only belongs to appearances, not to things-in-themselves. This can also be deemed a forerunner of the logical positivist idea that necessity is a result (or product) of our conventions, not of the world itself. Of course, just as conventions belong to minds, so too do appearances.

In Kant’s view, freedom (i.e., independence from causal necessity) is only found in things-in-themselves. That is, the substance of the mind is also a thing-in-itself. Therefore, the mind too is free from causal necessitation. The only things that are subject to causal necessitation are the objects of experience. Things-in-themselves are free.

Thus, Kant believed that he managed to solve a very difficult problem: the problem of determinism. In Kant’s picture, “nature and freedom” can exist together. Nature is not free. However, things-in-themselves (including the mind’s substance) are free. These different things can “be attributed to the very same thing”. That is, human beings are beings of experience, and also beings-in-themselves. The experiential side of human nature is therefore subject to causal laws, whereas the mind (or “soul”) transcends causal necessitation. We are, therefore, partly free, and partly unfree.

Kant has a particular way of expressing what he calls “the causality of reason”. Because reason is free, its cognitions and acts of will can be seen as examples of “first beginnings”. A single cognition or act of will is a “first cause”. In other words, it’s not one of the links in a causal chain. If it were a link in such a possibly infinite causal chain, then there would be no true freedom.

First beginnings guarantee persons freedom of the will and self-generated (or self-caused) cognitions. (In contemporary literature, such first beginnings are called “originations”.)

What does it mean to say that something just happens ex nihilo?

Would such originations therefore be arbitrary or even chaotic — sudden jolts in the dark of our minds? Wouldn’t they also be like the quantum fluctuations in which particles suddenly appear out of the void?

Why would such things guarantee us freedom, rather than making us the victims of chance or randomness?

Knowledge of Things-in-Themselves

Kant argued that we can’t know anything about things-in-themselves (in the singular German, Ding an sich), yet he also argued that “we are not at liberty to abstain entirely from inquiring into them”.

So can we have knowledge of things-in-themselves or not?

Perhaps Kant meant that although we can indeed inquire into things-in-themselves, nevertheless it will be a fruitless endeavour. Or perhaps Kant’s point was psychological: we have a psychological need to inquire because “experience never satisfies reason fully”. Alternatively, although our inquiries into things-in-themselves won’t give us knowledge, we can still offer conjectures or suppositions about them. That is, we can speculate about the true nature of things-in-themselves, even though we’ll never have knowledge (in the strict sense) of them. [Schopenhauer criticised this stance. See here.]

In Kant’s scheme, then, there are questions that will press upon us despite the fact that answers to them may never be forthcoming. Kant, again, cites his earlier examples of evidence- or experience-transcendent issues such as “the duration and magnitude of the world, of freedom or of natural necessity”. However, experience (alone?) lets us down on these issues. Reason, on the other hand, shows us “the insufficiency of all physical modes of explanation”.

Can reason truly offer us more?

Again, Kant tells us that we can’t be satisfied by the appearances. The

“chain of appearances [] has [] no subsistence by itself [] and consequently must point to that which contains the basis of these appearances”.

Of course, it’s reason itself which will “hope to satisfy its desire for completeness”. However, reason can’t satisfy our yearnings by giving us knowledge of things-in-themselves. So “we can never cognise these beings of understanding”, but “must assume them”. However, it is reason that “connects them” with the sensible world (and vice versa). It must follow, therefore, that although “we can never cognise these beings of understanding”, there must be some alternative way (or ways) of understanding them.

No comments:

Post a Comment