This essay is mainly about Eugene Wigner’s position on the wave function and its relation to what he called “sensations” and “impressions”. It also connects all of that to idealism, and the role of consciousness in quantum mechanics.

Writers must be careful when discussing Eugene Wigner’s philosophical views.

For a start, no one could deny that his paper ‘Remarks on the Mind-Body Question’ (which I’ll be concentrating upon) has inspired at least some New Agers, idealists and spiritual commentators. (At least those who feel the need to mention scientists to back up what they already believe.)

Actually, it’s lines and passages from that paper that New Agers and spiritual commentors quote…. Or, even more accurately, the often-used quotes from that paper are what such people quote. In other words, they quote the quotes, rather than the paper itself. (As can be seen in the main image for this essay, requotes often appear in the form of social-media memes.)

Despite all that, ‘Remarks on the Mind-Body Question’ itself is far from being New Age, mystical, spiritual, or idealist.

So it’s now also worth noting here that Wigner actually began to play down the role of consciousness in quantum mechanics. Specifically, he came to believe that the idea that “consciousness causes the collapse of the wave function” leads to solipsism. In his own words, Wigner argued that “[s]olipsism may be logically consistent with present quantum mechanics”.

That said, even a full commitment to consciousness collapsing the wave function isn’t necessarily tied to idealism. Of course, it has been tied to idealism. Yet it still doesn’t need to be an idealist position. In fact, there are ways of reading wave-function collapse which actually work against idealism, and which some theorists have picked up on.

What’s more, Wigner also came to emphasise that what’s true at the quantum scale, isn’t also true of “classical” or macroscopic objects and events. Thus, Wigner’s (later?) positions don’t help idealism (or a consciousness-first position) at all. After all, in idealism, literally every object and event (including trees, human beings, acts of sexual intercourse, etc.) is the product of consciousness. Alternatively put, everything is a manifestation (or instantiation) of “universal consciousness”.

[Thus, many commentators have deemed the ‘Wigner’s friend’ thought experiment to be a reductio ad absurdum. See next essay.]

In any case, it’s much less the case that Wigner was an idealist, and more the case that some people stress that he believed that quantum mechanics “spell[ed] the end for materialism”. Indeed, Wigner did write the following words:

“The principle argument against materialism [] that it is incompatible with quantum theory. The principle argument is that thought processes and consciousness are the primary concepts, that our knowledge of the external world is the content of our consciousness.”

At the beginning of ‘Remarks on the Mind-Body Question’, Wigner also told his readers that

“most physicists in the then-recent past had been thoroughgoing materialists who would insist that ‘mind’ or ‘soul’ are illusory, and that nature is fundamentally deterministic”.

[See note 1 for a quick take on these two “anti-materialist” passages from Wigner.]

All the above said, Wigner himself (at least in one place) did use the word “idealist” about what he called “the concept of the real”. In his own words:

“The concept of the real to be arrived at shows considerable similarity to that of the idealist. As the title indicates, it is formulated as a dualism.”

This isn’t much help to idealists or consciousness-first philosophers either.

For a start, the position Wigner advanced in that paper (‘Two Kinds of Reality’) only shows “considerable similarity to that of the idealist”. Thus, even the strong adjective “considerable” still shows that Wigner didn’t deem his “concept of the real” to be actual idealism. (Of course, it might have been idealist without Wigner himself having fully realised that.) What’s more, Wigner then immediately says that his concept of the real is actually “formulated as a dualism”.

Was Eugene Wigner a Positivist?

It’s fairly hard to decide if Eugene Wigner was an old-style empiricist, a positivist, a phenomenalist, or simply a physicist who endorsed the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics.

One main reason for this is that Wigner wasn’t a philosopher. This means that he didn’t really write enough to go on. That said, Wigner did write more philosophical stuff that most physicists.

In any case, it doesn’t really matter which precise ism Wigner falls under because all the philosophical (as it were) schools mentioned above are basically part of the empiricist tradition. Thus, all the differences between these schools don’t really matter that much within the specific and limited context of this essay.

This issue is complicated even more when it comes to Wigner’s philosophy of mathematics, as perfectly expressed in his well-known article ‘The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences’. It would be difficult to place that work within the domain of either empiricism or positivism. Indeed, it’s been classed as an expression of mathematical realism by many, and even as Pythagoreanism by other commentators…

Such is the anomalous nature of mathematics. And that’s something that positivists, empiricists, and materialists have freely acknowledged.

To return to the central theme.

Wigner did often use the terms “impressions” and “sensations” in his paper ‘Remarks on the Mind-Body Question’. Thus, this usage alone squares fairly well with the following definition of empiricism:

“In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological view which holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience.”

However, perhaps the term “phenomenalism” best suits Wigner’s position.

According to one form of phenomenalism, “a physical object is a kind of construction out of our experiences”. In more detail:

“Phenomenalism is the view that physical objects, properties, events (whatever is physical) are reducible to mental objects, properties, events.”

Now, in Wigner’s case, it can be said that “sensory experience” and “mental objects, properties, events” are what we have to go on in the case of wave functions and scientific experiments. In fact, Wigner will be quoted explicitly stating this later…

Okay, then. Perhaps “positivism” is a better term for Wigner’s positions.

After all, a few decades before Wigner’s paper, various logical positivists strayed into the territory of physics and argued that all scientific (or “synthetic”) statements must be reducible to “perceptions” and “direct observations”.

[Of course, it now need hardly be said that all the various isms just discussed had their own problems.]

Finally, it’s now also worth stating that none of the above directly argues (or even implies) that Wigner was at one with 18th-century British empiricists, the logical positivists, etc. Indeed, the following passage alone highlights one fundamental difference:

“It is at this point that the consciousness enters the theory unavoidably and unalterably. If one speaks in terms of the wave function, its changes are coupled with the entering of impressions into our consciousness. If one formulates the laws of quantum mechanics in terms of probabilities of impressions, these are ipso facto the primary concepts with which one deals.”

Why this passage isn’t purely empiricist — or even positivist — will hopefully become clear in what follows.

Wigner on “Impressions” and “Sensations”

As already stated, there’s little in Eugene Wigner’s words which can be directly (or strongly) tied to either idealism or to mysticism.

That said, what about Wigner’s many uses of the words “sensations” and “impressions” in his ‘Remarks On the Mind-Body Question’?

Whereas New Agers, idealists and spiritual commentators nearly always talk about consciousness in very vague terms, Wigner himself mainly refers to “impressions” and “sensations”.

Relevantly, the word “consciousness” (in this context at least) has grown to have an idealist or even mystical ring to it, whereas Wigner’s “impressions” and “sensations” just seems like an old-style empiricist way of putting things.

Yet Wigner himself did refer to “consciousness” a few times in that paper!

In fact he did so in the same passages in which he referred to “impressions” and “sensations”.

For example, Wigner wrote the following:

“I believe that the present laws of physics are at least incomplete without a translation into terms of mental phenomena.”

Of course, Wigner’s sensations and impressions occur within consciousness — where else could they occur? [See note 2 on this spatial metaphor.] So, in that rudimentary sense, 18th century empiricists might just as easily and justifiably used the word “consciousness” about their own empiricism — had that word been as fashionable way back then as it is today. [John Locke did use the word “consciousness” in the 1690s, but not really in the way that many do so today.]

In any case, Wigner stating that we “rely on sensations” isn’t a commitment to idealism. It’s broadly an empiricist position, and such a position dates back (in various forms) to the 18th century. (Arguably, it dates much further back than that— see here.) Such a position was also adopted — if in a “logical” form — by the logical positivists… We’ve had phenomenalism too!

In terms of detail, Wigner wrote the following passage:

“All that quantum mechanics purports to provide are probability connections between subsequent impressions (also called ‘apperceptions’) of the consciousness, and even though the dividing line between the observer, whose consciousness is being affected, and the observed physical object can be shifted towards the one or the other to a considerable degree, it cannot be eliminated.”

As far as that passage is concerned, it can be argued that Wigner believed that he was taking the Copenhagenist line to its (as it were) logical conclusion. After all, Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, Max Born etc. also stressed (or at least used) the words “impressions” and “sensations”. [See here.] Rudolph Carnap and other logical positivists, on the other hand, used terms such as “cross-sections of experience”. Indeed (as already stated), the emphasis on “sense impressions” goes back to the British empiricists of the 18th century.

Yet none of the examples cited — certainly not Carnap and the logical positivists — could be deemed to be idealists or people with idealist or “mystical” inclinations…

That’s unless empiricism (if of a 20th-century kind) is actually taken to be a kind of idealism. [There has been some debate about this when it came to Bishop Berkley. See note 3.]

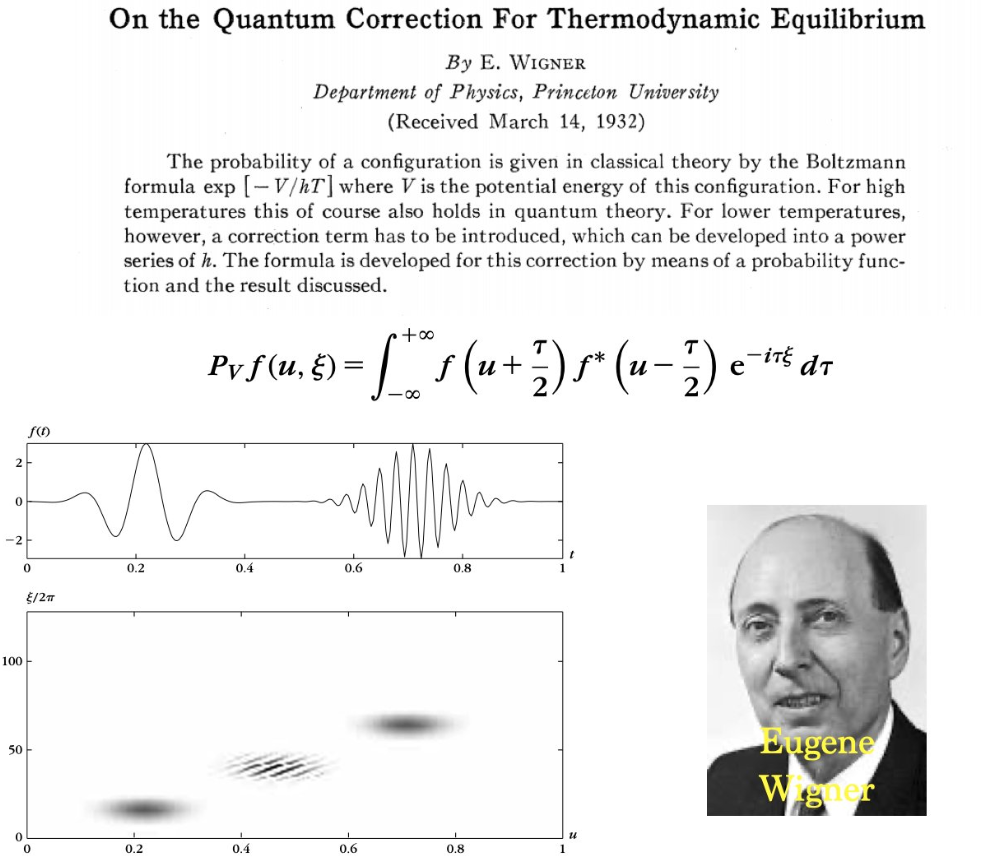

All that said, it’s now important to tie Wigner’s words about impressions and sensations to the wave function. After all, the wave function was central to quantum mechanics after 1926, and Wigner himself had much to say about it.

Wigner on Impressions and the Wave Function

Eugene Wigner himself described the wave function in the following way:

“This is a mathematical concept [] it is composed of a (countable) infinity of numbers. If one knows these numbers, one can foresee the behavior of the object as far as it can be foreseen. More precisely, the wave function permits one to foretell with what probabilities the object will make one or another impression on us if we let it interact with us either directly, or indirectly.”

Going into more detail, Wigner then tied the wave function to observations:

“Given any object, all the possible knowledge concerning that object can be given as its wave function. [] [T]he wave function is only a suitable language for describing the body of knowledge — gained by observations — which is relevant for predicting the future behaviour of the system.”

And elsewhere:

“[K]nowledge of the wave function does not permit one always to foresee with certainty the sensations one may receive by interacting with a system.”

Wigner again stressed “impressions” (or “sensations”) when he wrote the following words:

“The information given by the wave function is communicable. If someone else somehow determines the wave function of a system, he can tell me about it and, according to the theory, the probabilities for the possible different impressions (or ‘sensations’) will be equally large, no matter whether he or I interact with the system in a given fashion.”

Wigner’s words above are really at one with the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics. As already stated, Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, etc. often stressed “sensations” and “impressions” too. However, Bohr himself, for example, didn’t often use the word “consciousness” in these specific respects. That said, Wigner quotes Bohr using precisely that word — but not about the wave function or even about quantum mechanics! (Wigner: “In the words of Niels Bohr, ‘The word consciousness, applied to ourselves as well as to others, is indispensable when dealing with the human situation’.”

More relevantly, it can be supposed (at least at first) that Wigner goes beyond plain-old positivism (or even Copenhagenism) when he added these words:

“[E]ven though the dividing line between the observer, whose consciousness is being affected, and the observed physical object can be shifted towards the one or the other to a considerable degree, it cannot be eliminated.”

Now that is truly something that you’d expect a 20th century quantum physicist to write.

Notes:

(1) There are problems with Eugene Wigner’s account of materialism: (1) Materialism isn’t necessarily incompatible with quantum theory. However, quantum theory certainly was at odds with 19th-century materialism in the 1920s. (2) Empiricists dating back to the 18th century wouldn’t have had any problems with stating that “sense impressions” (if not “thought processes and consciousness”) are “primary”, and that we gain access to the “external world” through our sense impressions (if not through “the content of our consciousness”). Indeed, that last point captured the very essence of empiricism!

Of course, idealists historically picked up on the fact that empiricists claimed to gain access to the external world via their sense impressions, and then they logically and philosophically questioned that position. Basically, idealists argued that empiricism led to (subjective) idealism. (It certainly did so with Bishop Berkeley.)

As for the second passage. It’s worth remembering that Wigner wrote the following words in 1961:

“[M]ost physicists in the then-recent past had been thoroughgoing materialists who would insist that ‘mind’ or ‘soul’ are illusory, and that nature is fundamentally deterministic.”

In 1961, “most physicists” didn’t “insist” upon such things. Apart from the fact that most physicists didn’t have much to say about the mind or soul (at least not qua physicists), they certainly — as a whole — weren’t against all mentions of the “mind”. On the other hand, perhaps many physicists would have had a problem with the soul. Better, with the word “soul”. That’s unless the word “soul” was simply deemed to be a synonym of the word “mind” in those days.

So perhaps Wigner really meant philosophical physicists or simply philosophers.

Well, even many materialist philosophers didn’t have a serious problem with discussing the mind before 1961. They might sometimes have had a radical take on the mind. (Such as with Gilbert Ryle’s book The Concept of Mind from 1949.) However, they wouldn’t have said that the “mind is illusory”. And that was for the simple reason that it had been given materialist, behavioural, functionalist, etc. explanations before Wigner wrote his words in 1961…

Now what about consciousness?

Well, that’s another matter…

(2) Of course, the nature — and even existence — of consciousness itself is also contested.

For example, I used the words “sensations and impressions occur within consciousness” in the essay above. Note the two words “in consciousness”. Surely that’s a spatial metaphor. In other words, why can’t sensations, impressions and other mental things actually constitute consciousness, rather than be in it?

(3) Some writers have argued that Bishop Berkeley’s empiricism morphed into what they called subjective idealism. Other writers have argued that it was such a thing from the very beginning.

Berkely’s philosophy also ties in with 21st century idealism in that God fulfils much the same role as “universal consciousness” (or “cosmic consciousness”) does. That’s in the sense that whatever is not directly perceived by a single subject (or even by a collective of subjects), is perceived by God himself (“God in that gap”) in Berkeley’s philosophy. In the case of “cosmic idealism”, on the other hand, all objects and events are, not perceived by “monotheistic God”: they’re actually instantiations of Universal Consciousness. (To the idealist Bernardo Kastrup, the brain, trees, acts of sexual intercourse, etc. are “images” or “representations” of consciousness.)

No comments:

Post a Comment