Stephen Jay Gould’s neat, tidy and sharp separation of values from facts, as well as religion from science, can itself be seen as an expression of his own political values. Rhetorically, Gould’s idea of what religion is seems to have been a product of his own imagination. And, in that imagination, religion completely abided by Gould’s own political sensitivities. Perhaps, then, it was only Gould’s view that religion should “keep[] itself away from science’s turf”, not that it has actually done so.

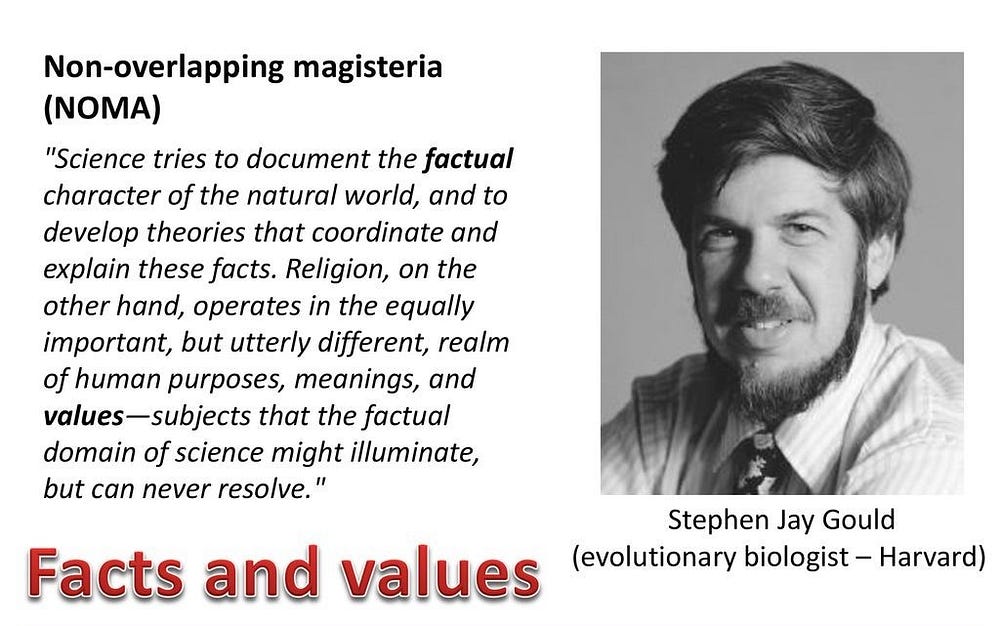

In his book Rocks of Ages: Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life, the American palaeontologist, evolutionary biologist and historian of science Stephen Jay Gould (1941–2002) argued that science and religion are what he called “nets”. Science is a net which captures certain phenomena. And religion is a different net which captures very different phenomena.

Moreover, these nets have

“a legitimate magisterium, or domain of teaching authority, and the two domains do not overlap”.

It will be argued that Gould is telling us what should be, not what is. Rhetorically, then, Gould’s idea of what religion is seems to have been a product of his own imagination. And, in that imagination, religion completely abided by his own political and diplomatic sensitivities.

Fact and Value: Science and Religion

In the following passage, Stephen Jay Gould went into some detail about the fact-value distinction as it applies to science and religion:

“Science tries to document the factual character of the natural world, and to develop theories that coordinate and explain these facts. Religion, on the other hand, operates in the equally important, but utterly different, realm of human purposes, meanings, and values — subjects that the factual domain of science might illuminate, but can never resolve.”

It almost seems like a statement of the obvious to say that it is outright false to claim that religion restricts itself to “human purposes, meanings, and values”. Religion has also had tons to say (as well as do) about “the factual character of the natural world”. (Do I really need to give examples here?)

Gould’s claim that religion and science are “two magisteria [which] do not overlap” clearly ignores the fact that religion (or religions in the plural) has had very much to say on facts and physical reality. His claims also ignore (or simply play down) the fact that the many and various miracles of religion are supposed to have impacted on physical reality in very specific ways. In addition, prayers are also believed to have concrete effects on the physical world.

The British evolutionary biologist and author Richard Dawkins (see note at the end of this essay) expressed his more abstract position on Gould’s fact (science)-value (religion) distinction in the following:

“[I]t is completely unrealistic to claim, as Gould and many others do, that religion keeps itself away from science’s turf, restricting itself to morals and values.”

Dawkins added:

“A universe with a supernatural presence would be a fundamentally and qualitatively different kind of universe from one without. The difference is, inescapably, a scientific difference. Religions make existence claims, and this means scientific claims.”

It is simply false to claim that religion has kept itself to itself, not only “unrealistic”.

So surely what Gould claimed is actually normative, rather than factual.

Perhaps, then, it was Gould’s view that religion should “keep[] itself away from science’s turf”, not that it actually has done so, and will continue to do so in the future. It certainly hasn’t done so in the past. And, clearly, that’s still the case today…

Indeed, isn’t all this obviously the case?

Gould also stated the following:

“‘Do we violate any moral codes when we use genetic technology to place a gene from one creature into the genome of another species?’ represent questions in the domain of values.”

This passage just seems so categorical and dichotomous. A student wouldn’t get away with writing it.

Perhaps Gould did get away with this philosophical ineptitude because his prose style is so literary, and therefore hard to pin down. (Many commentators have praised Gould’s writing style. See ‘Analysis of Stephen Jay Gould’s Writing Style’.) Perhaps it’s also because Gould was so highly regarded as a scientist.

However, the statements above (from Gould) are not themselves scientific. His comments on the neat, tidy and sharp separation of facts from values (or vice versa), and science from religion, can themselves be seen as an expression of Gould’s political values.

Gould’s NOMA (“non-overlapping magisteria”) idea is also extremely artificial. Indeed, it’s a position driven by a desire for political diplomacy.

[Gould once wrote: “Religion is too important to too many people for any dismissal or denigration of the comfort still sought by many folks from theology.”]

In detail. Even if there is no role for scientific (or sociological, psychological, evolutionary, etc.) scrutiny and data on the nature of values, then why should we accept (or trust) anything any religion has to say on it? This isn’t to reject religion’s input out of hand. However, Gould either/or religion/science binary is so crude that it must surely have the consequence that science is automatically excluded from any input on the nature of values — as least values as expressed by religion (or by religions).

And what about philosophy and other forms of critical thinking which are neither scientific nor religious? After all, Gould’s NOMA idea is itself neither scientific nor religious — it’s primarily political.

Moreover, what if the sciences do have something to say on the values we’ve adopted about gene transferal (Gould’s own example) or about any other subject? And what about the evolutionary origins of our values and ethics?

Sure, scientists may well make incorrect claims on these issues. Yet scientists make correct claims too. However, Gould’s neat, tidy and political division leaves no role for any science when it comes to religious values.

[I suspect that Gould might have denied this last claim when expressed in that simple and categorical way. He might have argued — or implied — that there is a role for science when it comes to values… as long as that role doesn’t involve the strong criticism of religion.]

And what about the “moral codes” which Gould said that scientists and others “violate”? What if they are pernicious moral codes? What if they are historically contingent or tribal moral codes?

In these cases, then, the sciences can help with the moral codes themselves, not just with the “facts”.

So what can evolutionary theory and the sciences generally tell us about values and morals?

As British science writer and journalist Matt Ridley puts it (see here), morals involve human behavior, which is observable. And what is observable is open to scientific scrutiny.

Some religious people may now respond by arguing that many claims in evolutionary theory aren’t (always?) based on anything that’s literally (or obviously) observable. They will also stress the theoretical nature of many claims about evolution itself.

In addition, a distinction can be made, and will be made, between the human expressions of values and moral positions, and their abstract or religious (as it were) reality. That is, according to religious people (or monotheists), values and moral truths exist timelessly in the mind of God. And according to some philosophers (such as moral realists), values and moral truths exist timelessly in some abstract space (or domain), and even in the concrete world itself, without having any necessary connection to either God or religion.

To sum up. The core of Gould’s NOMA idea is a consequence of his somewhat naive belief in a chasm (or at least large gap) between fact and value.

Now E.O. Wilson provides an interesting counterpoint to Gould on the fact-value distinction, if not also on the science-religion distinction.

E.O. Wilson on Deriving an Ought From an Is

Some readers may agree with the following passage from Daniel Dennett:

“If ‘ought’ cannot be derived from ‘is,’ just what can ‘ought’ be derived from? Is ethics an entirely ‘autonomous’ field of inquiry? Does it float, untethered to facts from any other discipline or tradition? Do our moral intuitions arise from some inexplicable ethics module implanted in our brains (or our ‘hearts,’ to speak with tradition)?”

In tune with the Dennett passage above, one can say that if the ought (or values) can’t be derived from “facts” (or from the scientific is), then religious values (at least) must indeed be completely autonomous. Indeed, perhaps we can’t derive values from any other domain. (Except, perhaps, philosophy or personal whim.)

The passage from Dennett also squares fairly well with E.O. Wilson’s position.

Edward Osborne Wilson (1929–2021) was an American biologist and naturalist. Wilson has been called “the father of sociobiology”. (He has also been called “the father of biodiversity” for his environmental advocacy.)

E.O. Wilson attempted to provide a scientific account of what he called “ethics”, if not what Gould called “values”. In addition, Wilson seemed to believe that an ought can be derived from an is, which Gould clearly didn’t believe.

[Various philosophers have offered us very intricate examples and analyses of how an ought can be derived from an is — see here. However, none of them seem to bear much of a relation to Gould’s position on religion and values.]

If religion is truly an autonomous “magisterium”, then its values can’t be derived from scientific facts or, indeed, from what is (i.e., not anything outside the religious what is).

That said, whereas Gould’s NOMA (i.e., “non-overlapping magisteria”) fails because it is primarily political in nature, Wilson’s position fails because his overall position on the is-ought distinction is (I believe) philosophically flawed.

[Wilson, in turn, believed that philosophy is a waste of time primarily because he — like many physicists and other scientists — believed that all philosophers ignore all science. See here.]

More relevantly, E.O. Wilson took almost the exact opposite position to Gould.

Whereas Gould demanded that science must keep out of the magisterium of religion, and that religion must keep out of the magisterium of science, Wilson believed that values and ethics (if not religion itself) are the sole domain of science.

It’s not surprising, then, that someone who believed in (universal) scientific consilience should have believed that ethics (if not religion) is a suitable subject for scientific scrutiny. (Consilience: “the principle that evidence from independent, unrelated sources can ‘converge’ on strong conclusions”.)

[It’s interesting, and not coincidental, that there were both scientific and political conflicts between Gould and Wilson. In fact, it can be argued — and many people have — that the scientific conflicts were largely political in nature, at least on Gould’s part. See here and here.]

Where Do Values Come From?

So how did E.O. Wilson explain science’s relatively new interest in ethics? Wilson argued:

“The objective meaning of ethical precepts comprises the mental processes that assemble them and the genetic and cultural histories by which they evolved. Those who think that an is/ought gap exists have not reasoned through the way the gap is filled by mental process and history.”

So what do the words “the objective meaning of ethical precepts” mean?… Actually, it’s fairly clear what Wilson was getting at. Still, it’s an odd use of the words “the objective meaning of”.

Clearly, Wilson was offering what he took to be a purely descriptive position on “ethical precepts”, not a normative one. Perhaps it follows from this (at least to some people) that it’s not ethics at all. Instead, it’s simply the scientific study of human ethics…

Wilson might well have dismissed that just-stated distinction.

In more detail, Wilson’s position can be seen as being purely scientific. That’s primarily because of statements such as the following:

“[E]thical precepts comprises the mental processes that assemble them and the genetic and cultural histories by which they evolved.”

These passages are about what we (whoever “we” are) have taken ethical precepts to be — not what ethical precepts are or what they should be. In that sense, then, it can be argued that Wilson’s position isn’t ethics at all. It’s the scientific (i.e., biological, neuroscientific, psychological, sociological, historical, etc.) study of human ethics.

Again, Wilson might well have taken these distinctions to be entirely bogus.

Yet isn’t ethics about how we should live, not how we have lived and how we do live?

More concretely, if Wilson believed that ethics is the study of the “genetic and cultural histories by which [ethical precepts] evolved”, then perhaps we can’t do much (or even anything) about such causal aetiologies of our ethical standards and principles. That’s the case because such things have already happened.

So is this is simply a causal account of what we believe and do in the ethical sphere?

As already stated, perhaps the study of the “mental process that assemble [our ethical precepts]” isn’t itself in the domain of ethics.

The Is-Ought Gap

Is the is/ought gap (or is-ought problem) bridged simply by reasoning about this “mental process and history”?

And is all this still in the magisterium of the is and was, not in the magisterium of the ought?

In detail. Even if we can fill in the gap (as Wilson put it) between the original causes of our beliefs and principles and the beliefs and principles themselves which followed, then does that bridging alone take us into the normative (or from the is to the ought) ? By filling in the causal gaps between causes and their effects (ethical precepts in Wilson’s book), then perhaps we still don’t move from the is to the ought (or from the descriptive to the normative).

So it’s still unclear why Wilson believed that the is/ought gap has been (or can be) bridged or “filled’ in the way he outlined.

To repeat. How will acquiring knowledge of the causes of our ethical precepts tell us whether or not our precepts are the right or the wrong ones? The causal or scientific facts of genetics (or whatever scientific data we can find or use) may indeed help us understand why we hold our ethical precepts. However, surely such facts alone can’t tell us why we should still hold them.

The English philosopher, writer and journalist Julian Baggini (1968 — ) sees some of these problems too. He writes:

“The idea here seems to be that ethical precepts — for example, the incest taboo — have their roots in particular genetic and cultural histories. It is clear that understanding such histories will be a useful tool in making ethical judgements. What is less clear is that this is a way out of the is/ought problem.”

We will indeed learn much from the aetiology of the incest taboo. However, we won’t learn whether or not that taboo is right or wrong from studying its “roots in particular genetic and cultural histories”. This knowledge, of course, may (again) help us in other ways. It will tell us, for example, that the taboo wasn’t passed down from heaven or that it’s not a non-natural precept which we somehow “intuit”. What’s more, all that scientific knowledge may — or will — indeed have an effect on our “ethical judgements”. However, that knowledge will not, at least not on its own, determine the conclusions of our ethical judgements…

So what will?

Wilson seems to have argued that we can indeed derive what we ought to do from what is (or what was) the case. That is, if something is genetically and/or culturally inscribed, then it must be a correct ethical precept…

Yet that clearly doesn’t follow.

What’s more, Wilson himself probably wouldn’t have accepted that this was his position when expressed in that categorical and simple way.

Our natural instincts, for example, may be bad instincts. As Baggini (again) puts it when he argues that

“we will do well to struggle to behave in ways that might seem contrary to our natural instincts, as, for example, with respect to ethical precepts rooted in a mistrust of strangers or in aggression responses”.

Of course certain natural instincts may also be good instincts. So it all just depends…

*********************

(*) See my essay ‘Stephen Jay Gould on Science and Religion: The Politics of Non-Overlapping Magisteria’.

Notes:

(1) Many people have a (to use the Reverend Ian Paisley’s words about his attitude toward Catholics) “perfect hate” of Richard Dawkins. This is hardly surprising when one considers the fact that religion had a “hegemonic” political, moral and social position for millennia — as Stephen Jay Gould himself noted. And Dawkins strongly criticises that hegemonic entity which Gould says people feel strongly about. (Gould: “Religion is too important to too many people for any dismissal or denigration [].”) Thus, people feel strongly about Dawkins largely because he criticises the religion they feel strongly about.

(2) Stephen Jay Gould wrote:

“[] I also know that souls represent a subject outside the magisterium of science. My world cannot prove or disprove such a notion, and the concept of souls cannot threaten or impact my domain. Moreover, while I cannot personally accept the Catholic view of souls, I surely honor the metaphorical value of such a concept both for grounding moral discussion and for expressing what we most value about human potentiality: our decency, care, and all the ethical and intellectual struggles that the evolution of consciousness imposed upon us.”

There’s a problem here. Religious people (Catholics in this case) do not see souls as having “metaphorical value”. They believe that souls are real or that they (well) exist. They also believe the the nature of souls is truthfully expressed in religious texts — and what is expressed in them bears no resemblance to what Gould says about them. In that sense, then, Gould’s view of souls can be deemed to be both insulting and condescending to religious people. Indeed, his view is also like “the God of the philosophers” in that it bears little resemblance to (as it were) the God of the people.

Of course, Gould might have replied to these accusations by saying that only to him are souls (as it were) metaphorical entities. In that case, then, when Gould discussed souls with religious people (if he ever did), then wouldn’t both parties have been talking about two different things or even talking passed each other?

My flickr account and Twitter account.