This is the follow up to my essay ‘Poststructuralism and Deconstruction as Forms of (Linguistic) Idealism’. My last essay was about Catherine Belsey’s poststructuralism, and how it’s strongly reliant (if implicitly) on linguistic idealism. (Belsey was a literary critic and academic.) This essay, on the other hand, attempts to show how Belsey and other poststructuralists/postmodernists use the philosophical position of linguistic idealism (if without using that term) as a means to further various political goals and causes.

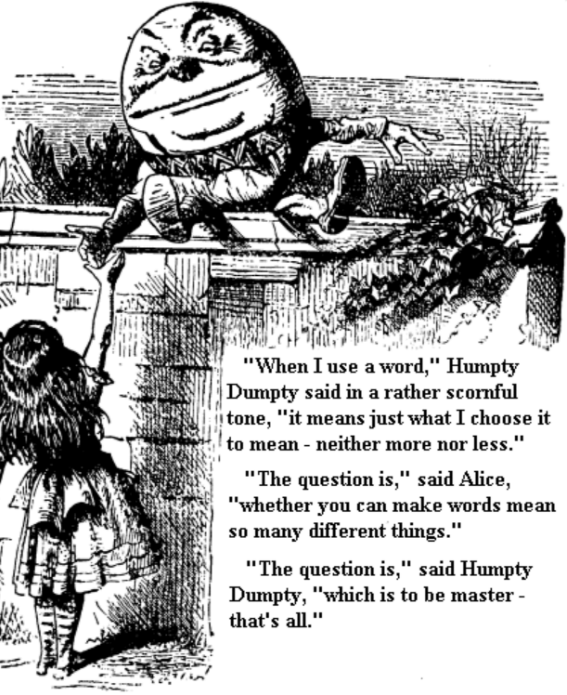

A critical (or biased) commentator may say that poststructuralists and postmodernist philosophers make words mean whatever they want them to mean.

Catherine Belsey herself was aware of this criticism.

Firstly, Belsey quoted a few words from Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass:

“‘When I use a word,’ Humpty Dumpty said in a rather scornful tone, ‘it means just what I choose it to mean — neither more nor less.’”

Alice, along with Belsey herself, recognised the problem here. Belsey continued:

“‘The question is,’ said Alice, ‘whether you can make words means so many different things.’

“‘The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be Master — that’s all.’”

There will be more on poststructuralism’s Humpty Dumpties later.

[It’s worth noting here that poststructuralism and postmodernism are essentially fused together in Catherine Belsey’s book, Poststructuralism: A Very Short Introduction.]

Catherine Belsey’s Politics

Catherine Belsey clearly had a political problem with the idea that in our own society

“we are compelled to conclude [] that some languages misrepresent the way things are”.

Belsey believed that “we” arrogantly assume that “our own language describes the world accurately”. Thus, if Belsey didn’t believe that the notion of accurately representing the way things are has any purchase, then she must either have believed that all ways of representing things do so accurately, or that no ways accurately represent the world.

More tellingly, Belsey (if not in these precise words) asked:

How dare we believe that we are right?

Similarly:

How dare we believe that others are wrong?

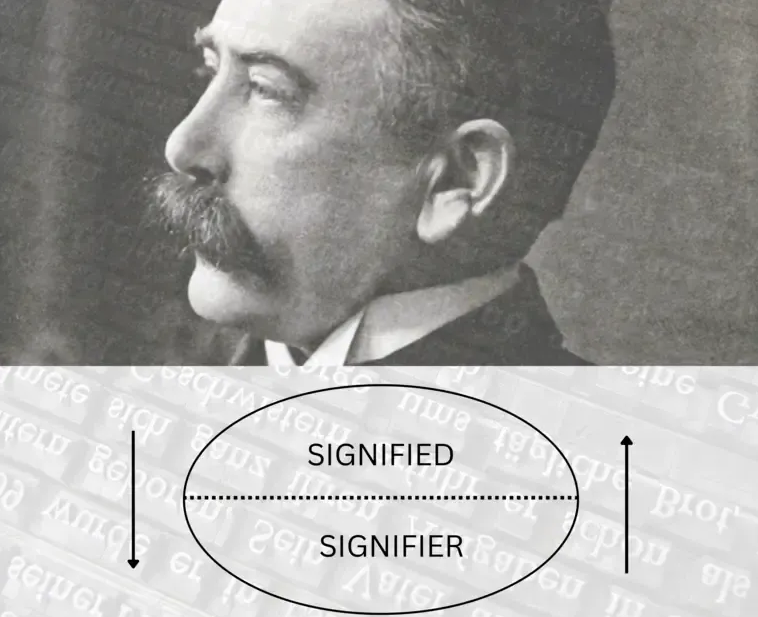

Belsey’s way out of this political outrage was to embrace linguistic idealism. More concretely, she rejected reference. (She actually used this word a couple of times.)

Belsey argued that we believe that “units [] exist unproblematically”. That is, we believe that our “reference to things” is unproblematic. Belsey, on the other hand, believed that things do exist problematically. Indeed, the very reference to things (or the world) is problematic.

Moreover, Belsey believed that things are actually “differentiated from one another by language itself”. In other words, the things we talk about are never (as she put it) “natural”. They are, instead, the artifacts of language. Thus, if things and the world are merely the artifacts of our language, then what right have we to state (or even believe) that “some languages misrepresent the way things are”?

(Belsey really means languages games by her word “languages” — as shall be shown in a moment.)

So what was Belsey’s alternative to this politically problematic acceptance of reference-to-things?

Belsey believed that it’s politically right to accept “other accounts of the world”. What’s more, in order to make philosophical sense of that, she believed (if not always explicitly) that we must abandon the world and reference. In other words, we must adopt linguistic idealism.

Take the following passage (now in full) from Belsey:

“We are compelled to conclude either that some languages misrepresent the way things are, while our own describes the world accurately, or that language, which seems to name units given in nature, does not in practice depend on reference to things, or even to our ideas of things.”

“[T]he units that seem to exist so unproblematically may be differentiated from one another by language itself, so that we think of them as natural [].”

This is a clear defence of the autonomy of language games.

(When you scratch the surface, some — even many — language games are actually excluded from Belsey’s pluralism and her embrace of diversity: such as the languages games of Nazis, fascists, nationalists, certain types of Christian, certain types of religious fundamentalists, patriots, conservatives, right-wingers, “neo-liberals”, “capitalists”, those people who’re against mass immigration, what she calls “reactionaries”, racists, Brexiters, etc.)

More relevantly, that autonomy of language games is a direct result of Belsey accepting linguistic idealism…

But all this is very esoteric.

What concrete political examples did Belsey herself give?

Firstly, Belsey cited a little history:

“A century ago many European nations were ready to impose their own classifications on other cultures, where imperial conquest made this possible.”

As ever, Belsey then offered her own political alternative. She continued:

“But the multicultural societies that have resulted from the decline of empire are willing to be more generous in their recognition of other accounts of the world, which is to say, other networks of differences.”

So in order to politically criticise former “European nations” and the (British) “empire”, Belsey needed to give up on the world and on things (or units). Or, at the very least, she needed to advance the idea that the world and things are exclusively the product of what the many and various language games decide they are.

However, this relativism(?) and linguistic idealism leads to obvious problems for Belsey very own political positions, causes and values.

Firstly, if everything goes, then languages games which include racism, colonialism, fascism, religious fundamentalism, white supremacy, nationalism, etc. must also go.

Yet earlier Belsey (obviously) didn’t apply her linguistic idealism, pluralism and stress on diversity to what Western nations and the British empire believed and did.

In fact, she was very selective.

In other words, in order to advance diversity (i.e., through linguistic idealism), Belsey had to exclude a hell of a lot (as already noted).

Of course, Belsey wouldn’t have accepted this inclusion-through-exclusion interpretation.

Yet it’s a clear consequence of her views.

When the world, units, things, reference (or referents), etc. are erased, then anything goes — and that includes racism, fascism, nationalism, religious fundamentalism, etc. Indeed, this is the very point that many Marxists have made against views like Belsey’s. [See my next essay.]

My own position is (to some degree at least) backed up by the American philosopher Thomas A. McCarthy, who basically argued that if there is no truth, correspondence, facts, things (or units), etc., then poststructuralists have literally nothing to go on — from a political perspective. All there can actually be is a situation of different language games (or phrase regimes — see later) being at (ideological) war with each other.

McCarthy himself offered the (political) requirement that we should accept shared content (determined by a shared world and shared things) between all languages. He also argued that surely only such a language — the language that deconstruction rejected or deconstructed — can liberate what Belsey herself refers to as “the big Other”.

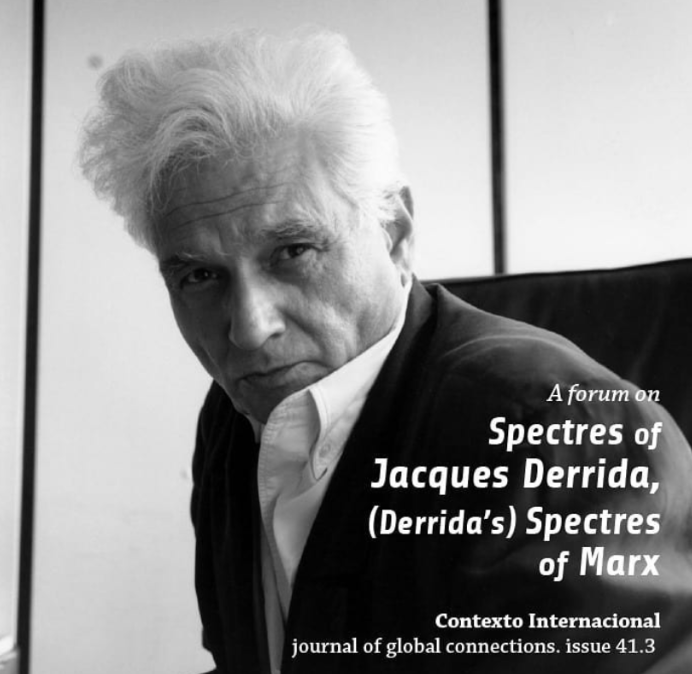

“Deconstruction can hardly give voice to the excluded other. The wholesale character of its critique of logocentrism deprives it of any language in which to do so.”

That’s why deconstruction (as Marxists have indirectly put it) couldn’t even hint at anything directly (rather than tangentially) political in any everyday sense. Hence, the ineffable, obscure and (well) pretentious prose.

This is McCarthy again:

“[Is it] merely by accident that [Derrida’s] writings contain little analysis of political institutions and arrangements, historical circumstances and tendencies, or social groups and social movements, and no constructions of right and good, justice and fairness, legitimacy and legality?”

Isn’t it the case that justice, legality, legitimacy, fairness, etc. are examples of transcendental signifieds in Derrida’s philosophy? Thus, Derrida’s only interest in similar terms (or similar things) was to violently deconstruct them. (Up until his later writings at least.) Indeed, if he hadn’t done that, then his whole enterprise would have… well, deconstructed itself.

If we now return to Belsey’s quotation of the Humpty Dumpty passage from Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass.

Poststructuralists/Postmodernists as Humpty Dumpties

Belsey did acknowledge (i.e., when discussing Humpty Dumpty earlier) that “[m]eaning is not at our disposal, or we could never communicate with others”.

Basically, Belsey was critical of the possibility of a (to use a term she uses — see here) “private language”. (So is just about everyone else!) In other words, she argued against purely subjective creations (or inventions) of what she called “meanings”…

However!

Belsey was very much in favour of language games.

Or, at the very least, Belsey accepted that language games existed, and that they are (or simply could be) at odds with each other.

Yet language games are deemed to be beyond the merely subjective — they are intersubjective.

As Belsey herself put it:

“We learn our native language, and in the process learn to invoke the meanings other people use.”

Belsey moved one step beyond this basic philosophical point about languages and communication, and added a political slant to it. She wrote:

“To reproduce existing meanings exactly is also to reaffirm the knowledge our culture takes for granted, and the values that precede us — the norms, that is, of the previous generation.”

To repeat. According to Belsey, there can be no private language. However, there can be (some? many? numerous?) language games.

So Belsey critically states that communication would be impossible if it relied on private languages, yet her take on language games makes these (Wittgensteinian? Lyotardian?) entities take on the same role as (private) subjects in the argument against private languages.

To be clear.

The possibility of a private language is ruled out by Belsey (again, as it is by just about everyone else), at the very same time as she argues that one language game is (or at least can be) incommensurable with another language game.

Thus, Belsey’s position on language games is similar to the French philosopher and sociologist Jean-François Lyotard’s own position. Unlike Belsey’s term “language games”, Lyotard used the (clearly more political) term “phrase regimes”. (This was most fully enunciated in his book The Differend: Phrases in Dispute. See also Lyotard’s notion of the differend.)

Lyotard argued that the concepts, terms, beliefs, aims, desires, etc. of each phrase regime are incommensurable with those of other phrase regimes.

All this means that Belsey having a problem with the possibility of a private language (i.e., of a single human person) didn’t mean that she also had a problem with a lack of commensurability between different language games. Indeed, that lack of commensurability is both stressed and endorsed by Belsey (as it was by Lyotard).

What’s more, the incommensurability thesis is stressed and endorsed for purely political reasons.

Belsey wrote:

“In this sense, meanings control us, inculcate obedience to the discipline inscribed in them.”

Sure, that sentence is fairly non-political (if somewhat hyperbolic). However, now take the following passage, in which Belsey told us that “Derrida argued” that

“[c]ulture is always ‘colonial’, in that it imposes itself by its power to name the world and to instil rules of conduct”.

The Point is Not to Refer to the World…

Belsey throws down the gauntlet with this statement:

“If meaning is a matter of social convention, it concerns and involves all of us.”

That’s basically a call for her readers (or for academic phrase regimes) to create (or invent) new meanings which serve the political causes and goals that Belsey herself endorsed. Indeed, Belsey more or less stated exactly that in various places.

For example, Belsey told us that “individuals can alter [language], as long as others adopt their changes”. She then relates all this specifically to poststructuralism (by inference, to linguistic idealism too). She wrote:

“Poststructuralism is difficult to the extent that its practitioners use old words in unfamiliar ways, or coin terms to say what cannot be said otherwise.”

Belsey’s acknowledgements above at least partly account for the difficulty in reading poststructuralist texts.

For a start.

Don’t readers need to already know that “old words” are being used “in unfamiliar ways” before they attempt to understand poststructuralist texts?

However, if readers don’t know this, then they’ll be reading old words in old ways.

What’s more, isn’t Belsey’s talk of neologisms and using old words in new ways a hint that readers need to belong to the poststructuralist (as it were) academic tribe before they can understand poststructuralist texts? Or as some Marxists have put: How will that philosophical and academic exclusivity work politically?

Readers will also need to know why old words are being used in unfamiliar ways. In other words, why don’t poststructuralists use new words (i.e., neologisms) to express new ideas?

So is there some kind of (as it were) subversive game going on here? A game in which old words are used in deliberately unfamiliar (or new) ways?

Well, of course there is!

Belsey and other poststructuralists have freely admitted that there is such a subversive game going on.

Added to the problems (i.e., the ones which will be encountered by those people who aren’t members of the poststructuralist academic tribe) is the problem of poststructuralists “coin[ing] [new] terms”…

And they’ve certainly done that!

Yes - there’s a huge lexicon of coined terms in poststructuralism.

It’s also difficult to decipher what Belsey means by the words “to say what cannot be said otherwise”. Some readers may suppose that this is like the terms “quark”, “Internet”, etc., which were used to refer to things which either didn’t previously exist or which weren’t previously known.

However, is there really a parallel between, say, the term “gene” and the poststructuralist term “trace”, or between “quark” and the poststructuralist term “logocentrism”?

In any case, Belsey acknowledges that the many new coinages of poststructuralists haven’t been accepted by everyone. She wrote:

“This new vocabulary still elicits some resistance, but the issue we confront is how far we should let the existing language impose limits on what it is possible to think.”

The way Belsey expressed this situation is to paint all members of the “resistance” as knuckle-dragging luddite reactionaries.

Is that really the case?

Most readers will be very happy with at least some new words or terms (even with some “old words [used] in unfamiliar ways”), but not be happy with all new terms or words.

Belsey knew that.

She even wrote that “we set out to modify the language, annoying conservatives with coinages”.

Again, some (or many) readers may be happy with “dark matter” or “gigabyte”, but not be happy with the poststructuralist term “Other” or “intertextuality”. A reader may even be happy with some new non-scientific coinages such as “social media”, “troll”, “democratic socialism” (or “Alt Right”), and not be happy with other new terms.

So now take some controversial terms in the news at the moment:

“they” (used as a singular pronoun), “woke”, “cisgender”, “snowflake”, “womxn”, “fake news”, “disinformation”, “misinformation”, “Alt Right” (or “Alt Left”), “dog whistle”, “denialists”, “gaslight”, “hate”, “haters”, “culture wars”, “neo-liberal”, “toxic masculinity”, “toxic…”, “diversity”, “inclusion”, “heteronormativity”, etc.

Admittedly, some of these terms are little more than cheap-’n’-easy buzzwords (which are thrown around like confetti on social media). However, the point is that surely Belsey can’t have been arguing that literally all new terms should be accepted without question.

Of course, clearly Belsey didn’t believe that.

After all, would she have been happy with the (fairly) new terms “Alt Left”, “snowflake”, “woke puritanism”, “academese”, “cultural Marxism”, “taking over the institutions”, “Remoaner”, “Mickey mouse degrees” (at universities), etc?

All this means that there may well be a host of reasons for finding the numerous neologisms of poststructuralists — and others — to be philosophically, semantically and/or politically problematic.

So surely it can’t always be a case of reactionaries rejecting literally all semantic change purely and simply because it’s… well, change.

Conclusion

Admittedly, Catherine Belsey is a minor figure. However, she perfectly characterised the legions of academics who were — and who still are — beholden to poststructuralist and postmodernist (as well as their many derivations) thought and ideas.

And like those other academics, Belsey clearly expressed her own politics through these academic isms.

Indeed, she argued that her own politics — as displayed through the prism of poststructuralism — must be (or should be) both embraced and then practiced. (She did practice it, both academically and otherwise.) In Belsey’s own words:

“If meanings are not given or guaranteed, but lived all the same, it follows that they can be challenged and changed.”

Belsey herself did challenge the “meanings” of what she called “conservatives” and of many others. And she did so through the ideas of poststructuralism and postmodernism, which are (or were) themselves, in turn, highly dependent (or reliant) upon the philosophical position of linguistic idealism.

(*) The final essay in this series on Catherine Belsey will be about the many Marxist critiques of poststructuralism and postmodernism. More relevantly, some (even many) of these Marxist critiques have themselves focused on the linguistic idealism of poststructuralism and postmodernist philosophy.

This essay will also include the words of Belsey, along with criticisms from Noam Chomsky, Terry Eagleton, etc.

(**) See my ‘Poststructuralism and Deconstruction as Forms of (Linguistic) Idealism’.

My flickr account and Twitter account.