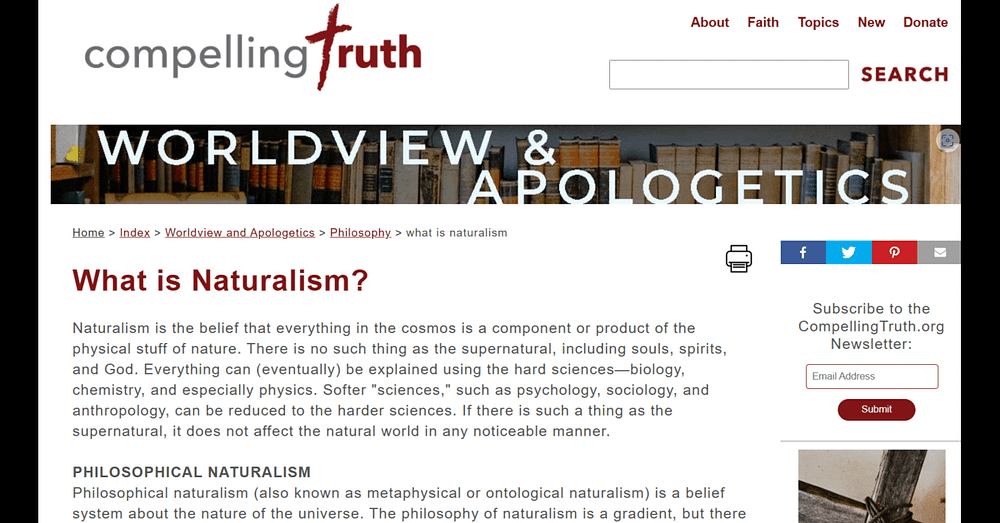

The words “Christian Apologist” are used in the title above because the passages quoted within the following essay come from the website ‘Compelling Truth: Worldview and Apologetics’. So the article I’ll be discussing (‘What is Naturalism?’) is an example of “apologetics” written by someone who states that he’s “presenting the truth of the Christian faith”.

[Part Two will follow shortly. This will be on this Christian apologist’s account of materialism and reductionism, as also seen within the context of naturalism.]

Introduction: What Is Naturalism?

In the introduction to the website ‘Compelling Truth: Worldview and Apologetics’, we’re told the following:

“The purpose statement of CompellingTruth.org is: ‘Presenting the truth of the Christian faith in a compelling, relevant, and practical way.’”

This website’s general introduction continues as follows:

“[] Our mission is to take the questions, issues, struggles, and disagreements that exist within the Christian faith and shine the truth of God’s Word on them. We believe the truth of God’s Word is compelling. []”

So it’s interesting to see how a Christian apologist sees naturalism.

The writer of ‘What is Naturalism?’ states the following:

“Naturalism is the belief that everything in the cosmos is a component or product of the physical stuff of nature. There is no such thing as the supernatural, including souls, spirits, and God.”

I personally do believe that almost “everything in the cosmos is a component or product of the physical stuff of nature”. [See the next essay on ‘What is Naturalism?’, and its section on materialism and reductionism.] I also believe that “[t]here is no such thing as the supernatural, including souls, spirits, and God”.

So I’m fairly happy with this definition from a Christian apologist. However, I’ll still make some points and qualifications.

For example, the words “component or product” (as “is a component or product of the physical stuff of nature”) need to be unpacked. In addition, words like “soul”, “spirit” and even “God” can be defined in ways which square with at least some kinds of naturalism. [See ‘Religious naturalism’.] However, the way that this Christian writer himself defines these words certainly doesn’t square with any kind of naturalism.

Finally, I can’t (as it’s often put) “prove” that souls, spirits, God, etc. don’t exist. That’s because these kind of things can’t be proved (or disproved) in any strict logical or mathematical sense. In fact, it’s a category mistake to ask for proofs or disproofs of these things.

Do Naturalists Believe That There Is No Emotion?

This account has it that, according to naturalism, “there is no emotion”.

Now even the Christian apologist who wrote this must know that naturalists don’t actually believe that.

Clearly, this writer is confusing disagreeing with a supernaturalist account of emotion, with naturalists actually believing that there is no such thing as emotion.

The problem is that this supernaturalist offers his readers a supernaturalist account of emotion (as well as other things), which, obviously, the naturalist doesn’t agree with. Yet that doesn’t mean that the naturalist actually believes that there’s no such thing as emotion.

The writer also includes “free will, purpose, soul, God” in the list of things which naturalists believe don’t exist…

Yet this list is problematic too.

There are certain naturalistic accounts of free will, purpose, the soul, and even God. Indeed, this Christian apologist admits as much when he tells us that

“although [naturalists] do allow for ‘purpose’ in human interaction, purpose that is driven by the survival of our DNA is not truly free will”.

So it depends on definitions. [See ‘Religious naturalism’.]

What’s more, even though this is an acknowledgment that there are indeed different non-religious accounts of emotion, purpose, free will, etc., these are still not very honest descriptions of those non-religious accounts. (For example, what does the clause “purpose that is driven by the survival of our DNA is not truly free will” even mean?)

Now let this Christian apologist himself make his own distinctions when it comes to what he calls “the human soul”.

Here the Christian writer distinguishes the human soul from “consciousness, mental thought, and value (both in preferences and morality)”, and concludes that (even?) naturalists believe that these things “do exist”.

However, to this Christian apologist, the human soul is above and beyond consciousness, mental thought, and value.

So what exactly is above and beyond all these things?

The answer is simple: the supernatural.

The Natural and the Supernatural

The next bit of ‘What is Naturalism?’ is fairly uncontentious. It goes as follows:

“If there is such a thing as the supernatural, it does not affect the natural world in any noticeable manner.”

It can be conceded that it is possible that some naturalists have used the same words as those quoted directly above. In other words, some naturalists might well have said that the supernatural “does not affect the natural world in any noticeable manner” (i.e., even if “there is such a thing” as the supernatural).

Yet how can something which doesn’t affect the natural world even be so much as a “thing”?

How could we know that something supernatural exists — or has any kind of reality — if it doesn’t impact on the natural world?

[The naturalist does face the problem of abstracta, at least in these respects.]

Of course, religious and “spiritual” people believe that what is supernatural does indeed impact on the natural world. This is the case with miracles, people being affected (or “moved”) by God, “religious experiences” generally, ley lines, clairvoyance, precognition, telekinesis, levitation, extrasensory perception, poltergeists, ectoplasm, invisible men, etc…

All these things are believed to impact on the natural world.

Thus, religious people obviously do believe that the supernatural affects the natural. Indeed, without such a relation, there wouldn’t even be such a thing as religion. In other words, all religions strongly and frequently stress the relation between the natural and the supernatural…

And that’s why scientists can’t help but have something to say about the religious accounts of the supernatural (or “the transcendent”).

In other words, there can’t really be two (as Stephen Jay Gould puts it) “independent magisteria” of science and religion. And that’s precisely because religions have it that the supernatural has a frequent and very important impact upon the natural. [See Non-overlapping magisteria.]

Science + Religion (the Natural + the Supernatural)

One common way that some (perhaps even many) religious people (a Christian apologist in this case) attempt to square science with religion is by stating passages similar to the following:

“[T]here is merit in attempting to discover God’s creation through the laws He has put into place.”

But then there’s a “but”…

Indeed, it’s a big but in this case.

This passage continues:

“But, as God has created the cosmos, it also makes sense to take His work and His character into consideration.”

Those two sentences are only the beginning. We then have the following passage:

“The Bible has specific things to say about geology and cosmology. Job 38 clearly shows that we cannot understand our world outside of the influence of God. Although a thorough scientific study will eventually bring us back to God’s written account, it would save time if we’d just believe Him in the first place.”

So here we have the natural (or what is studied by science) + the supernatural.

In other words, both science and religion are taken together as being part of the same package… Except, of course, that it can’t also be naturalism if we have + the supernatural. That would obviously defeat the object of naturalism. Quite simply, anything that includes + the supernatural can’t, by definition, be naturalism…

But can it be scientific?

Well, if we take science + the supernatural as part of the same equation, then obviously the science part is, well, scientific. And it’s equally obvious that the + the supernatural isn’t scientific.

So if the + the supernatural is acceptable, then surely anything deemed to be supernatural is also acceptable. Thus, we’ll have science + anything supernatural. After all, what grounds has, say, a Christian got for rejecting science + ley lines, or science + multiple gods, or science + pink pixies, or science + ectoplasm, or science + reincarnation, etc. other than scientific grounds?…

Well, he actually has religious grounds for rejecting these many denizens of the supernatural realm.

So someone — say, a Christian again — may have his own religious grounds for rejecting ley lines, polytheism, pink pixies, reincarnation, clairvoyance, precognition, telekinesis, levitation, extrasensory perception, poltergeists, ectoplasm, invisible men, monsters, extraterrestrial creatures, legendary creatures, etc…

But why should the Christian’s preferences when it comes to the supernatural realm concern the naturalist?

This would be a dispute between those who, say, on the one hand, believe in the virgin birth and the Trinity, and, on the other hand, those who believe in ley lines, polytheism or pink fairies. Thus, the only way that a naturalist — or anyone else for that matter - can enter this debate is by adopting a particular religion, and then battling it out from that particular religion.

Conclusion

Despite the self-designation ‘apologetics’, the article ‘What is Naturalism?’ is closer to being a political pamphlet (or a political opinion piece) than it is to being a philosophical or scientific article. That said, it was chosen because it’s actually quite faithful to most of the critical (or negative) accounts of naturalism I’ve read over the years — even form those who don’t explicitly defend religion.

So this account of naturalism does indeed often verge into political-pamphlet mode.

For example, it does so when it uses such phrases as “the horrifying consideration that…”, “the Bible refutes…”, (naturalists believe that) “psychology, sociology, and anthropology, can be reduced to the harder sciences”, (naturalism has it that) “the experiences of life such as pain, preference, desire, or emotion, also do not exist”, “scientists go so far as to deny a basic sense of self or even a sense of pain”, etc.

All this is straw-target (or even cartoonish) stuff.

What’s more, Compelling Truth portrays naturalists (as well as “materialists”) as almost literal demons who’re out to destroy everything of value.

It also claims that naturalists believe things which they clearly don’t actually believe.

Indeed, this account of naturalism doesn’t even attempt to argue that these (supposedly) extreme naturalist positions (or ideas) are the logical conclusion of naturalism. Instead, it deems them to actually be an explicit part of naturalism.

However, none of this is a surprise.

This account of naturalism (i.e., ‘What Is Naturalism?’) doesn’t actually quote a single naturalist, or quote a single sentence from a work on naturalism. Yet, and as already stated, not everything this account says about naturalism is false.