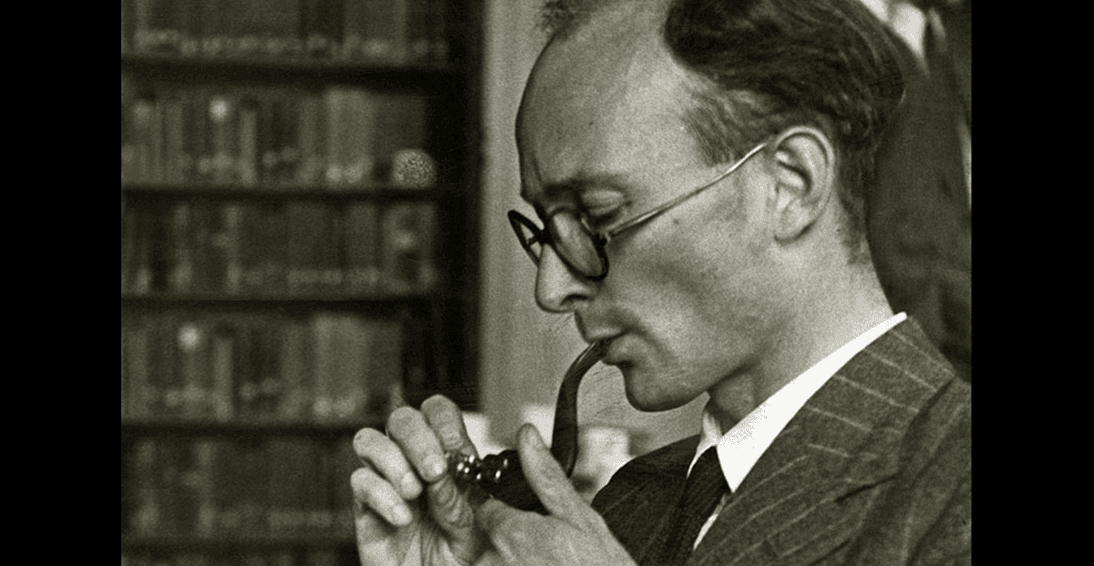

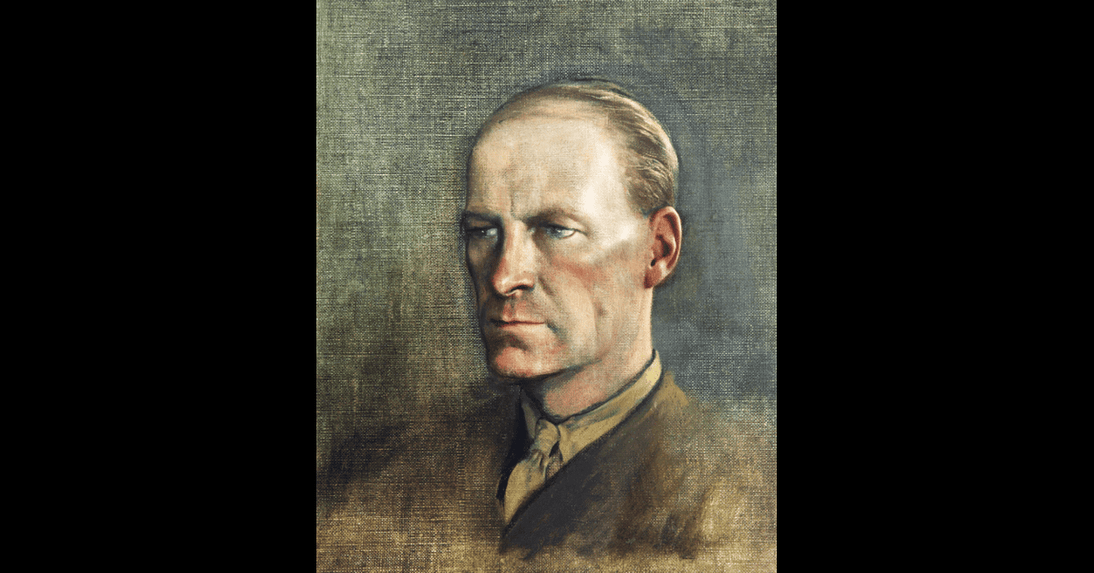

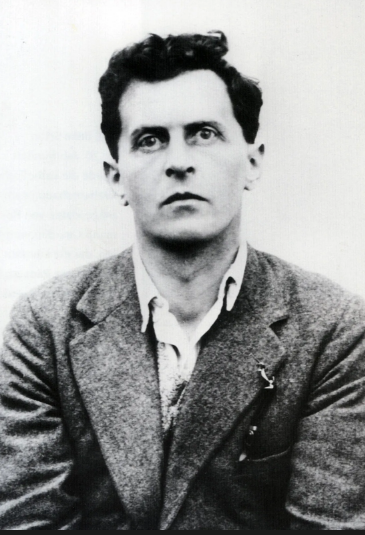

The following essay is on Gilbert Ryle’s account of the life and work of Ludwig Wittgenstein, as found in the article ‘Ludwig Wittgenstein’. This was published in 1951, the year of Wittgenstein’s death.

One gets the feeling that the English philosopher was somewhat annoyed by the (what can only be called) Wittgenstein Worship which existed when he wrote this article, and for some time before too. That said, Ryle did admire the Austrian philosopher, and was even inspired by him. What’s more, Ryle’s work of the early 1930s is said to have anticipated the “late” work of Wittgenstein.

Gilbert Ryle started off with a critical passage in which he mentions the problem with many of Wittgenstein’s followers at the time (i.e., 1951). He wrote:

“Philosophers who never met him — and few of us did meet him — can be heard talking philosophy in his tones of voice; and students who can barely spell his name now wrinkle up their noses at things which has a bad smell for him.”

It seems hardly possible that anyone, let alone more than one philosopher, could be heard talking philosophy in Wittgenstein’s own tones of voice. However, many of Wittgenstein’s early acolytes were young men, so perhaps that makes it rather less surprising. Of course, many other philosophers, over the years, have also elicited similar embarrassing tendencies from their followers.

Wittgenstein Worship was especially peculiar when one bears in mind certain facts about Wittgenstein’s life and works. This too is commented upon by Ryle in the following passage:

“Besides the *Tractatus*, he published only one article. In the last twenty years, so far as I know, he published nothing, attended no philosophical conferences; gave no lectures outside Cambridge; corresponded on philosophical subjects with nobody and discourage the circulation even of notes of his Cambridge lectures and discussions.”

These facts about Wittgenstein’s life do much to explain Wittgenstein Worship. One should note, for example, that Wittgenstein had only one book published in his lifetime, and that book was obscure and mystical to many. It can also be seen that he kept himself philosophically clean by restricting himself to only certain circles. (Wittgenstein once claimed to have never read much philosophy.) Current professors of philosophy and other academics, on the other hand, (to exaggerate a little) publish articles every other month, attend a conference every two weeks, give lectures all over the place, and would like everything they ever wrote to be published. And that’s why such people don’t have the mystical charisma and other-worldly charm that Wittgenstein had.

What about Wittgenstein’s work, specifically the Tractatus? Ryle wrote:

“[T]he *Tractatus* is, in large measure, a closed book to those who lack this technical equipment. Few people can read it without feeling that something important is happening, but few experts, even, can say what is happening.”

It can easily be argued that Wittgenstein became such a fashionable philosopher precisely because his Tractatus is a “closed book”. Indeed, it is to some extent a closed book even to those people who do have the “technical equipment”. (Hence, the often-used phrase: “You have misunderstood Wittgenstein.”) It’s also odd that even those who lack the technical equipment still “feel[] that something important is happening” when they read the Tractatus. So why is this the case? It can be suggested that it’s Wittgenstein portentous and mystical prose style that brings forth the feeling that something important is happening.

It’s worth saying here that Ryle wasn’t the only philosopher to make these kinds of critical remark. For example, take the words of Irving M. Copi:

“What one holds to be of greatest significance in the Tractatus will depend in great measure upon one’s interpretation of that work and one’s assessment of the correctness of its doctrines.”

Now for the words of Rudolf Metz:

“It is for the ordinary reader a book sealed with seven seals, of which the significance is only revealed to the most esoteric devotees, and which, as it seems to us, embodies a very peculiar combination of rigorous mathematical and logical thought and obscure mysticism.”

Ryle on Wittgenstein’s Philosophy

Of course, Ryle also discussed Wittgenstein’s actual philosophy in his article ‘Ludwig Wittgenstein’.

For a start, what’s been called “anti-philosophy” didn’t actually begin with Wittgenstein. According to Ryle: “Late in the nineteenth century Mach had mutinied against this view that metaphysics was a governess-science.”… And then we reach Wittgenstein’s own era. Ryle continued:

“By the early 1920s, this mutiny became a rebellion. The Vienna Circle repudiated the myth that the questions of physics, biology, psychology or mathematics can be decided by metaphysical considerations. Metaphysics is not a governess-science or a sister-science. It is not a science at all. [ ] Philosophy was regarded as a blood-sucking parasite; in England as a medicinal leech.”

Ryle then gave a concrete example of a real problem with metaphysics:

“The classic case was that of Einstein’s Relativity principle. The claims of professors of philosophy to refute this principle were baseless. Scientific questions are soluble only by scientific methods, and these are not the methods of philosophers.”

This “classic case” even inspired Richard Feynman’s well-known harsh and dismissive words about philosophy and philosophers. Feynman claimed, among other things, that “a surprisingly large number of philosophers, not only those found at cocktail parties [believed that] Einstein’s theory says all is relative!”. (Feynman wrote these words some 12 years after Ryle’s own words, and some 55 years after Einstein first published his work on Relativity.) It’s worth saying here that even today a contemporary philosopher, E.J. Lowe, believes that metaphysics trumps physics in that if the metaphysical positions and criticisms stand against scientific theories (or are true), then science must give way. [E. J. Lowe’s position — at least when it came to to certain issues, such as the nature of spacetime - can be seen in his chapter ‘Metaphysics’ in The Bloomsbury Companion to Analytic Philosophy. It’s of course been the cases that other scientists, if few of them, have also offered their criticism of Einstein’s Relativity, perhaps under the inspiration of their own philosophies and other philosophers’ views.]

Ryle then commented on something which characterised the philosophy of Wittgenstein in both his Tractatus period and in his late works. It’s here that Wittgenstein became metaphilosophical again. In this metaphilosophical mode, Wittgenstein, in the words of Ryle, “now avoid[ed] any general statement of the nature of philosophy”. He did so “not because this would be to say the unsayable, but because it would be to say a scholastic and therefore an obscuring thing”. Finally:

“In philosophy, generalizations are unclarifications. The nature of philosophy is to be taught by producing concrete specimens of it.”

Sure, but isn’t the statement “Generalizations are unclarifications” itself a generalisation, and thus an unclarification? (One would guess that there’s a hidden universal quantifier hidden in that statement.) As for “any general statement of the nature of philosophy”, how many times have readers heard or read the statement, “Philosophy is…” (Philosophy is this or that.) Indeed, how many times have readers read the statement, “Consciousness is…” Etc. Some philosophers, and nearly all philosophical amateurs, constantly say x is y without argumentation or evidence. Thus, the philosophies of such people often become a long list of (often prophetic) statements delivered without pausing for breath. Alongside this is the general vice of over-indulging in generalisations which, again, make such philosophies prophetic and rhetorical. Wittgenstein believed that philosophical generalisations were “unclarifications” — and they were unclarifications precisely because they were generalisations. Instead of “general statement[s]” which may well titillate and excite, Wittgenstein suggested that we “produce[] concrete specimens” of what it is we’re trying to argue and say. Indeed, this approach is more accurately found in the Philosophical Investigations than it is in the Tractatus. That said, because Wittgenstein often focussed on concrete specimens (or examples), sometimes it’s hard to catch the general drift of his philosophising. In simple and critical terms, Wittgenstein’s philosophy often tends to jump from subject to subject because he concerned himself with the particular, rather than with the general.

Nonsense!

Most students of philosophy will be aware that Wittgenstein and the logical positivists often used the words “meaningless” and “nonsensical” to refer to certain metaphysical and other kinds of statements. What many people don’t also realise is that these words were used in a technical and stipulative manner, not necessarily as rhetorical devices. Thus, many philosophers and lay people have been offended by having their statements — and corresponding beliefs — categorised as “meaningless” or “nonsense”. Ryle himself is helpful here in that he clarifies these issues in a simple manner. He wrote:

“In Wittgenstein’s *Tractatus* this departmental conclusion is generalized. All logic and all philosophy are enquiries into what makes it significant or nonsensical to say certain things. The sciences aim at saying what is true about the world; philosophy aims at disclosing only the logic of what can be truly or even falsely said about the world. This is why philosophy is not a sister-science or a parent-science; that its business is not to add to the number of scientific statements, but to disclose their logic.”

Of course, the word “significant” is just as much in need of an explanation, as well as a justification, as the words “meaningless” and “nonsense”. However, the explanation for these technical and stipulative terms is made clear by Ryle in his article. In simple terms, only the sciences can say truthful (or false) things “about the world”. Any other seemingly-factual statements, especially metaphysical ones, are deemed to be meaningless or nonsense. They’re deemed to be so because although they have the surface grammar of being fact-stating sentences, they are not so…

But we must bite the bullet here.

If metaphysical and other statements are meaningless or nonsense because they can’t be either true or false, then the kind of philosophical statements (or sentences) which “aim[] at disclosing only the logic of what can be truly or even falsely said about the world” must be meaningless or nonsense too. And that, of course, is one of the well-known conclusions Wittgenstein made in his own Tractatus. (Philosophy doesn’t “add to the number of scientific statements”, it only “disclose[s] their logic”.) This meant that, to Wittgenstein, philosophy can never be a science.

Some readers may now be wondering what is “the logic” of such scientific and non-scientific statements. In very simple terms, that’s already been explained in that the logic of scientific statements is that they are empirical sentences about the world, and, thus, they can be verified by observation. The logic of metaphysical statements, on the other hand, is that they aren’t empirical sentences about the world, and, thus, they can’t be verified by observation.