The American philosopher Ted Sider believes that “the realist picture requires the ‘ready-made-world’” and that “there must be a structure that is mandatory for inquirers to discover”. Is he right about all this?

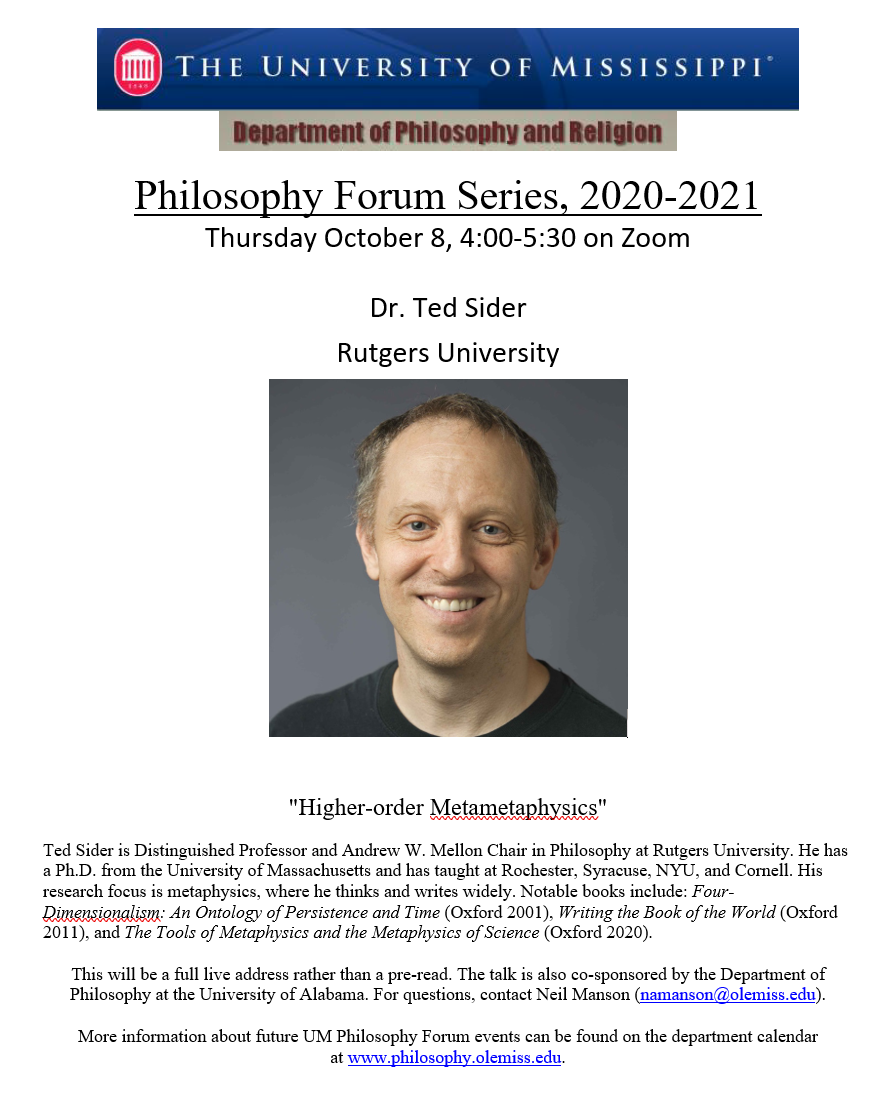

Theodore “Ted” Sider is an American philosopher who concentrates on metaphysics. He is Distinguished Professor of Philosophy at Rutgers University.

Sider has also taught at the University of Rochester, Syracuse University, New York University and Cornell University. He has had three books published and written many papers.

Introduction

Ted Sider (sometimes deemed to be an “analytic metaphysician”) tells us what he takes metaphysics to be.

Alternatively put: Sider tells us what he believes metaphysics should be.

In his paper and chapter, ‘Ontological Realism’, Sider writes:

“The point of metaphysics is to discern the fundamental structure of the world.”

What’s more, “[t]hat requires choosing fundamental notions with which to describe the world”. Indeed Sider continues by saying that “no one other than a positivist can make all the hard questions evaporate”. Finally:

“There’s no detour around the entirety of fundamental metaphysics.”

Sider also makes it plain that metaphysics asks fundamental and important questions by asking his readers this question:

“Was Reichenbach wrong? — is there a genuine question of whether spacetime is flat or curved?”

The obvious response to that question is say it’s a scientific (i.e., not a metaphysical) question… That’s unless it’s the case that metaphysicians (such as Sider himself) can offer insights on this issue which physicists (at least qua physicists) are simply incapable of.

More technically, Sider cites W.V.O Quine’s work (as well as the quantification of metaphysical structure) as the means to answer the question above (as well as other similar questions).

Ted Sider on Objective Structure

What is realist in Sider’s “ontological realism” is what he calls “objective structure”. This does the work formerly done (i.e., in the history of metaphysics) by such things as objects, events, laws, essences, kinds, etc.

The main force behind all of Sider’s positions is his metaphysical realism. That classification isn’t such a big problem because that’s how Sider (if sometimes implicitly) classes himself. For example, he writes:

“A certain core realism is, as much as anything, the shared dogma of analytic philosophers, and rightly so.”

It’s certainly not the case that “core realism” has been a “shared dogma of analytic philosophers”. That’s simply a generalisation. There have been anti-realists, idealists, positivists, pragmatists, instrumentalists and all sorts of other philosophers (even a small number of panpsychists) within analytic philosophy.

Thus Sider may (or must) mean something more subtle by his claim above.

Perhaps he means this:

Deep down and when push comes to shove, “realism is a shared dogma of analytic philosophers”, as it is for almost everyone.

Does Sider really believe that almost everyone (including all/most analytic philosophers) believes that the “world is out there, waiting to be discovered”? That may well be the case. However, it may only be the case in a very vague way — a way which often doesn’t amount to much. Indeed even most anti-realists and idealists, for example, believe that something is out there (see note).

In other words, there’s a world (or an x) that exists regardless of minds…

So?

And it’s what Sider says next that problematises his position.

Sider argues that this world that’s “out there, waiting to be discovered” and also that it’s “not constituted by us”.

Those two claims depend on so much.

Minds, conceptual schemes, language, sensory systems, brains, etc. don’t literally make the world in the sense of creating its spacetime, matter, forces, etc. (That said, some idealists — such as Professor Donald Hoffman with his “conscious realism” — do believe that.) However, minds may well — even if in some subtle or limited sense — structure/shape/determine/colour (or whichever word is appropriate) the world. That is, anti-realists — and almost the majority of philosophers — believe that we never get the world “as it is” in its pristine condition. More importantly and as Karl Popper and, later, Richard Rorty once put it: “the world doesn’t tell us what to say about it”.

In that sense, then, Sider is simply wrong when he argues that

“[e]veryone agrees that this realist picture prohibits truth from being generally mind-dependent”.

The problematic word above is, of course, “truth” — and that usage may explain Sider’s ostensibly extreme philosophical position.

Ted Sider on Truth

Again, it’s simply not the case that “everyone agrees” that the world (or nature) is “generally mind-independent”. Sure, it may depend, for one, on how that phrase is taken. That is, people may well believe that truth is in some (or many) ways mind-independent. However, metaphysics itself is about the world and its “fundamental nature”.

Thus the truths Sider is talking about are about the world.

So do we ever have guaranteed truth in metaphysics?

We don’t in physics, cosmology and in all the other sciences. So perhaps we don’t in metaphysics either.

Yet, in once sense — a sense given by some metaphysicians and philosophers — truth is by definition mind-independent. However, Sider seems to be fusing that position with our metaphysical statements about the world.

So is it that we can argue that if such statements are true, then what makes them true is “mind-independent”? That doesn’t follow. At least it doesn’t automatically follow.

On the other hand, perhaps we simply don’t have metaphysical truths in the first place. Perhaps we only have metaphysical positions. And, as already stated, metaphysical positions involve mind, language, concepts, brains, psychologies, conceptual schemes, contingent sensory-systems, human intellectual and social history, etc. And all these things can be said to (rhetorically) pollute our metaphysical purity.

Thus perhaps we never have the Realist Truth Sider speaks of in metaphysics — analytic or otherwise.

Ted Sider on the Ready-Made World

Sider also states the following:

“The realist picture requires the ‘ready-made-world’ that Goodman (1978) ridiculed; there must be structure that is mandatory for inquirers to discover.”

There may well be a (to use a phrase also used by Hilary Putnam) “ready-made-world”. However, perhaps Nelson Goodman’s point was that we don’t have access to it except through our contingent minds, languages, conceptual schemes, brains, sensory-systems, etc. All those things make it the case that we must colour (or interpret) that ready-made-world. Thus, to us embodied human beings, it’s no longer a ready-made world: we make it (at least in a loose or vague sense).

What’s more, if all the above is the case, then grand claims about the independent nature of the world amount to very little.

The other point is that even if there is a mind-independent-ready-made-world, that doesn’t automatically mean that everyone — not even every realist philosopher — will says the same things about it. (The English philosopher Crispin Wright — in his book Truth and Objectivity — believes that we would say the same things if we all had what he calls “Cognitive Command”.) It doesn’t even guarantee that contradictory things won’t be said about this ready-made-world. Indeed contradictory things have been said about it — even by metaphysical realists!

So the world’s mind-independence doesn’t guarantee discovering Sider’s “mandatory structure” (just as it didn’t guarantee C.S. Pierce’s “future convergence”).

Yet Sider doesn’t accept any of this.

Instead, Sider believes that there are “predicates that carve nature at the joints, by virtue of referring to genuine ‘natural’ properties”. He continues:

“The world has a distinguished structure, a privileged description. [] There is an objectively correct way to ‘write the book of the world’.”

Well:

How does Sider know all that?

Does Sider know all that through metaphysical analysis and then referring to the “best science”?

Neither of these things can guarantee that we (not Sider’s words) “carve nature at the joints” or obtain metaphysical truths about the world. Again:

(1) How would we know when we have a “privileged description”?

(2) How do we know what that privileged description is?

What’s more, is there only one “objectively correct way to ‘write the book of the world”? Even if there is, then how does Sider know that?

Sider also gets to the heart of the matter (at least in the debate between metaphysical realism and what he calls “deflationism”) when he states the following:

“Everyone faces the question of what is ‘real’ and what is the mere projection of our conceptual apparatus, of which issues are substantive and which are ‘mere bookkeeping’.”

That’s certainly not true of “everyone”. It’s just true of many — not even all — philosophers. Sure, it’s true that many laypersons are concerned with what is real. However, they don’t also think in terms of the possibility that it’s our “conceptual apparatus” that hides — or may hide — the Real. Many laypersons believe that other things hide “what is real”: lies, propaganda, “the media”, politicians, religions, mind-altering drugs (or a lack of such drugs) and even science and philosophy.

Nonetheless, the philosophical issue of realism does indeed spread beyond philosophy. Take Sider’s comments on science.

Ted Sider on Science

Sider writes:

“This is true within science as well as philosophy: one must decide when competing scientific theories are mere notational variants. Does a metric-system physics genuinely disagree with a system phrased in terms of ontological realism feet and pounds? We all think not.”

Now take Donald Davidson’s less theoretical example of centigrade and Fahrenheit. According to Davidson, these are simply two modes of presentation of the same thing (see here).

However, Sider asks if the same can be said of “a metric-system physics” and a “ontological realism feet and pounds”.

Does Sider’s position have something to do with what’s called “empirical or observational equivalence” and theoretical underdetermination? If it does, then theories which are empirically equivalent needn’t also be theoretically (or philosophically) identical. Sider continues:

“Unless one is prepared to take the verificationist’s easy way out, and say that ‘theories are the same when empirically equivalent’, one must face difficult questions about where to draw the line between objective structure and conceptual projection.”

Sider also asks what he calls “deflationists” a couple of good questions.

Ted Sider on Metaphysical Deflationists

Firstly, Sider asks this question:

“Is your rejection of ontological realism based on the desire to make unanswerable questions go away, to avoid questions that resist direct empirical methods but are nevertheless not answerable by conceptual analysis?”

It’s hardly surprising — if we take the positions above (alongside the earlier reactions) — that Sider himself has heard “[w]hispers that something was wrong with the debate itself”. Despite that, according to Sider:

“Today’s ontologists are not conceptual analysts; few attend to ordinary usage of sentences like ‘chairs exist’.”

It’s tempting to say that ontologists should indulge in a bit of conceptual analysis!

That said, it’s not the case that conceptual analysis should be the beginning and the end of metaphysics; only that it may help things (just as a basic knowledge of science does).

Indirectly, Sider does comment on conceptual analysis; or at least on what he calls “ontological deflationism”. He writes:

“These critics — ‘ontological deflationists’, I’ll call them — have said instead something more like what the positivists said about nearly all of philosophy: that there is something wrong with ontological questions themselves. Other than questions of conceptual analysis, there are no sensible questions of (philosophical) ontology. Certainly there are no questions that are fit to debate in the manner of the ontologists.”

In terms of conceptual analysis and ontological deflationism being relevant to the composition and constitution of objects, Sider writes:

“[W]hen some particles are arranged tablewise, there is no ‘substantive’ question of whether there also exists a table composed of those particles, they say. There are simply different — and equally good — ways to talk.”

Sider also attacks what he calls “conventionalism”.

Ted Sider on Conventionalism

Sider argues that if we accept conventionalism, then we “demystify philosophy itself”.

In his book, Riddles of Existence: A Guided Tour of Metaphysics (co-written by Earl Conee), Sider puts his case more fully:

“If conventionalism is true, philosophy turns into nothing more than an inquiry into the definitions we humans give to words. By mystifying necessity, the conventionalist demystifies philosophy itself. Conventionalists are typically up front about this: they want to reduce the significance of philosophy.”

That is strong stuff!

Is conventionalism really that extreme?

Is Sider’s account of conventionalism even correct?

At first blast, Sider’s passage above sounds more like a description of 1930s and 1940s logical positivism!

In any case, do conventionalists (if they exist at all) really argue that philosophy is “nothing more than any inquiry into the definitions we humans give to words”? Or do conventionalists simply stress the importance of our words and our conventions when it comes to philosophy?

Moreover, surely the conventionalist doesn’t believe that it’s only a question of word-definitions: he also stresses our concepts. That is, how do our concepts determine how we see, conceive of, or interpret the world? Indeed if it were all just a question of word-definitions, then conventionalists would be little more than linguists or even lexicographers.

Perhaps conventionalists, on the other hand, don’t give up on the world at all. Perhaps they simply argue that our words, concepts, conventions, sciences and indeed our definitions are important when it comes to our classifications, descriptions, analyses, etc. of the world.

Is Ted Sider a Platonist?

When Sider argues that “[b]y demystifying necessity, the conventionalist demystifies philosophy itself”, he implies that philosophy is nothing more than the study of necessity! In that case, it’s no wonder that the conventionalist (real or otherwise) “wants to reduce the significance of philosophy” if that’s really the case.

Sider’s position seems to be a thoroughly Platonic (as well as perhaps partly Aristotelian) account of philosophy (i.e., with its obsession with necessity and essence).

Is that really all that philosophy is concerned with — essence and necessity? Indeed, if the conventionalists’ supposed exclusive focus on word-definitions is wrong, then perhaps obsessing about necessity and essence is too.

Arguably, this was largely true of Plato and indeed Aristotle. But what about 20th- and 21st-century philosophers? Indeed what about Hume and many other pre-20th century philosophers?

Now we can see more evidence of Sider’s Platonist notion of philosophy’s role when he answers the question, “What is philosophy?”

Sider answers that question five times, thus:

(1) Philosophy “investigates the essences of concepts”.

(2) Philosophy “seek[s] the essence of right and wrong”.

(3) Philosophy “seek[s] the essence of beauty”.

(4) Philosophy “seek[s] the essence of knowledge”.

(5) Philosophy “seek[s] the essences of personal identity, free will, time, and so on”.

According to Sider, conventionalists believe that “these investigations ultimately concern definitions”. Not only that, according to the conventionalist, “[i]t seems to follow that one could settle any philosophical dispute just by consulting a dictionary!”.

It would be nice to know if there is such a conventionalist animal who really believes all this. As stated earlier, Sider’s account of conventionalism really seems like an account of 1920s and 30s logical positivism — or perhaps an account of the later ordinary language philosophy of the 1950s. And surely no contemporary philosopher is such an old-fashioned animal.

Again, Sider’s take on conventionalism seems thoroughly old-fashioned in nature. What’s more, his Platonist account of philosophy (or its role) seems even more old-fashioned. This, of course, isn’t automatically to argue that Sider’s positions are false or incorrect simply because they’re old-fashioned. It’s only to say, again, that they’re old-fashioned. So perhaps all Sider’s philosophical positions are still correct or true.

***************************

Notes:

(1) It’s interesting that Ted Sider stresses the importance of structure in both science and metaphysics considering the fact that analytic metaphysicians (ones just like Sider himself) are against, for example, ontic structural realists; whom also stress structure.

(2) An Objective Idealist (at least of a kind) can believe that, say, Universal Consciousness and “entangled conscious agents” are out there. And an anti-realist can believe that what’s responsible for “what we say” is out there; even though, when we say what we say, then that something we say is no longer about something that’s “mind-independent” — even if it is out there.