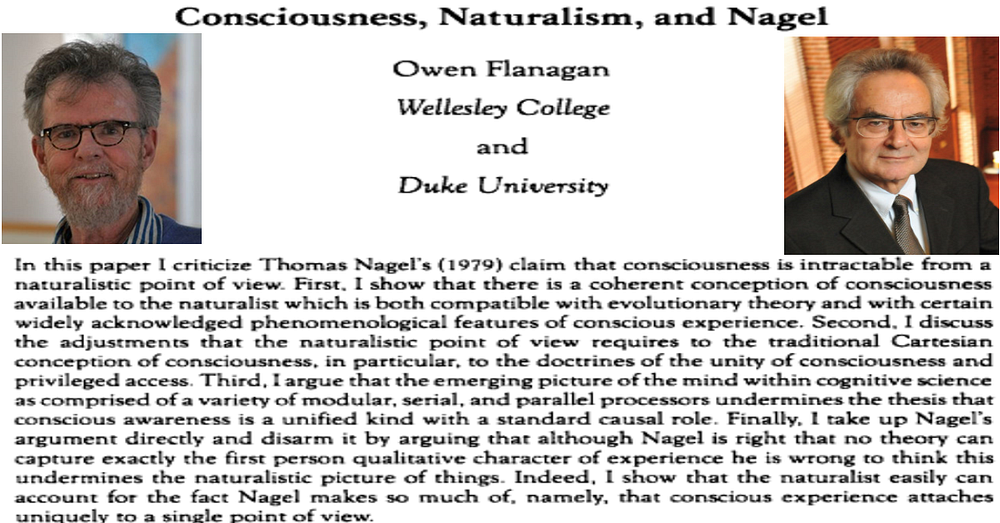

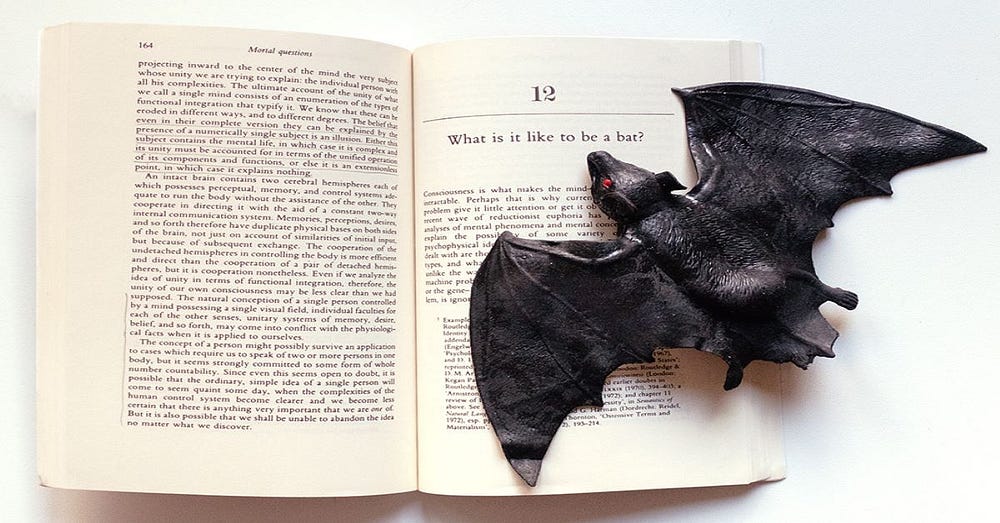

Owen Flanagan argued that Thomas Nagel was essentially asking, “What is it like for individual x to be individual y?”

“Insofar as I can imagine this (which is not very far) it tells me only what it would be like for me to behave as a bat behaves. But that is not the question. I want to know what it is like for a bat to be a bat.”

— — Thomas Nagel (From his ‘What is it like to be a bat’. The passage is here.)

“If the problem is that every attempt to understand the mental life of another must be from a particular point of view, this is a problem every subject of experience has in understanding every other subject of experience. Bats play no essential role in the argument whatsoever.”

— — Owen Flanagan (From his book, Consciousness Reconsidered. The passage is here.)

Introduction

Firstly, the following is a statement of the broad — and perhaps obvious - position advanced in this essay:

No individual person can experience or instantiate another individual’s (to use Thomas Nagel’s words) “point of view”.

More simply, no individual can be another individual. Therefore no individual can instantiate or experience another individual’s point of view.

… But so what?

All the words above are in reference to Thomas Nagel’s position. (Thomas Nagel is an American philosopher.)

So let’s get to the heart of Nagel’s philosophical stance; at least as it was noted by the American philosopher Owen Flanagan (1949 — ).

Firstly, Flanagan told us that Nagel has a problem with the situation that

“such a theory fails to capture what exactly conscious mental life is like for each individual person”.

Flanagan continued:

“Nagel’s continual mention of the way consciousness attaches essentially to a ‘single point of view’ indicates that this bothers him.”

More broadly, this is how Flanagan put things:

“Theorizing of the sort I have been recommending is intended not to capture what it is like to be each individual person but only to capture, in the sense of providing an analysis for, the type (or types) conscious mind and, what is different, consciousness person.”

So was Nagel making the blindingly-obvious logical point that x can’t be y? Sure, he might not have ever put it that simply… but that doesn’t matter.

Moreover, Nagel’s impeccable (if implicit) logical point (i.e., that x can’t be y) has little effect on either naturalism or physicalism. And that’s because both (if in basic terms) accept the law of identity.

Only an “individual person” can know “what it is like to be” that individual person. And Flanagan’s own take on this is that each individual has his, her or its own individual (causal) “hook-ups” to both himself/herself/itself and to the world. In detail:

“Naturalism can explain why only you can capture what it is like to be you. Only your sensory receptors and brain are properly hooked up to each other and to the rest of you so that what is received at those receptors accrues to you as your experiences.”

Flanagan continued:

“In the final analysis, your experiences are yours alone; only you are in the right causal position to know what they seem like. Nothing could be more important with respect to how your life seems and how things go for you overall [].”

And in more detail:

“It is because persons are uniquely causally well connected to their own experiences. They, after all, are the ones who have them. Furthermore, there is no deep mystery as to why this special causal relation obtains. The organic integrity of individuals and the structure and function of individual nervous systems grounds each individual’s special relation to how things seem for him [].”

Again, it is literally impossible for naturalism, physicalism or any other ism to get around this logical truth.

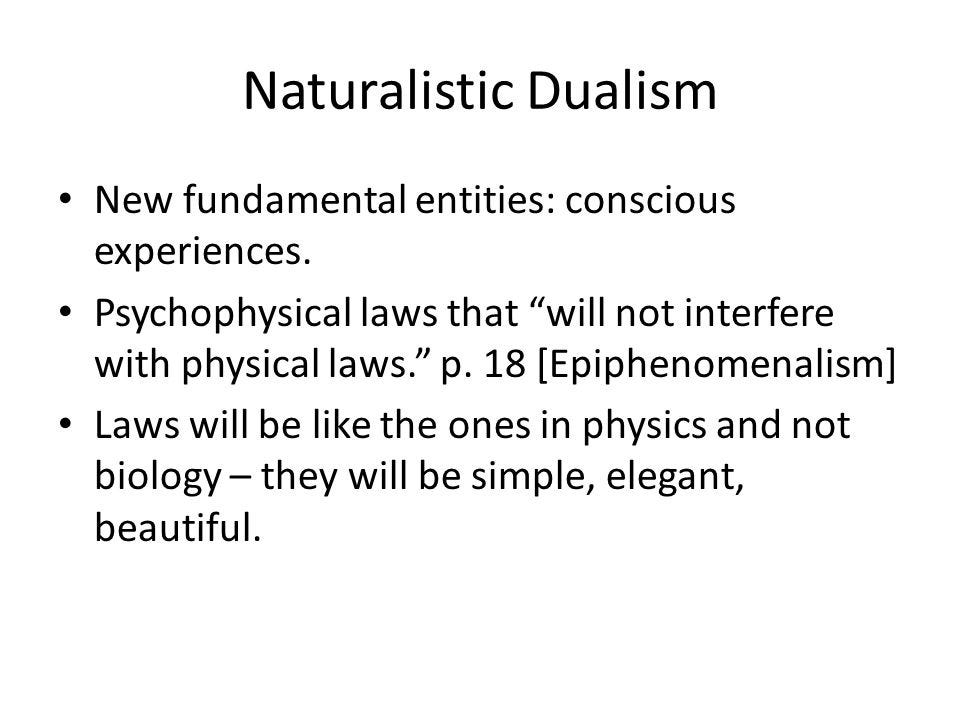

Of course even if it is the case that Nagel’s position is primarily motivated by the individual’s “point of view”, anti-physicalists may still argue that this isn’t the only (or even the main) argument against physicalism. That is, regardless of the logical uniqueness of the individual’s point of view, it’s still impossible to move from the physical (or from the brain) to consciousness or to experience. That is, no matter how strong and many the “correlations” are, there’s still something left out when it comes to the neuroscientific accounts of experiences, consciousness or “qualia”.

Another way to put this is that even if an individual human being or animal instantiated consciousness or experience but had no point of view (such as is the case with the lower animals), then a move from the physical to its experiences would still be problematic. After all, philosophers have long recognised the independence of consciousness from, particularly, self-consciousness and from all other higher-levels of mentality - and therefore from points of view too. Thus, in these cases, such animals don’t have a point of view. And that means that another individual can’t know what’s it’s like to have another’s point of view if that point of view isn’t instantiated in the first place.

X is Not Y

Thomas Nagel put his position clearly (if implicitly and tangentially) in the following way:

“This bears directly on the mind-body problem. For if the facts of experience — facts about what it is like for the experiencing organism are accessible only from one point of view, then it is a mystery how the true character of experiences could be revealed in the physical operation of that organism.”

And elsewhere (as quoted by Flanagan) Nagel also wrote:

“‘But when we examine their subjective character it seems that such a result is impossible. The reason is that every subjective phenomena is essentially connected with a single point of view, and it seems inevitable than an objective, physical theory will abandon that point of view.’”

In response to all that and more, Flanagan stated the obvious:

“If I am not you, I cannot grasp what it is like to be you.”

And Flanagan also put it almost as plainly in the following:

“Naturalism can explain why only you can capture what it is like to be you. Only your sensory receptors and brain are properly hooked up to each other and to the rest of you so that what is received at those receptors accrues to you as your experiences.”

Thus Flanagan pus the what-is-it-like-to-be show (with its hundreds — perhaps thousands — of articles, papers and books) largely down to the fact that an individual person can never be another individual (whether another human person or a different kind of non-human animal). Thus any given individual can never know what it is like to be that other individual.

Of course Flanagan put some technical neuroscientific meat on that basic claim by mentioning such things as “sensory receptors and [the] brain”. Still, it’s still an individual person’s sensory receptors and brain not being another individual's sensory receptors and brain that’s at the heart of this what-is-it-like-to-be story. That is, mentioning the extra detail that

“your sensory receptors and brain are properly hooked up to each other and to the rest of you so that what is received at those receptors accrues to you as your experiences”

is basically another way of saying that you can’t be someone (or some thing) else.

But why on earth is that (as it were) brute fact alone a threat to either naturalism or to physicalism?

In any case, Nagel often used the word “character” (as in “subjective character of experience”) to get his point across.

The Character of Another Individual’s Experiences

The following is Flanagan's take on Nagel’s word “character”:

“The equivocation is the source of the illusion that an understanding of some set of experiences necessarily involves grasping the character of these experiences.”

Here again we have the gross truth that one individual can’t be another individual. That is, this isn’t simply the case of not knowing what it is like to experience what another individual experiences…

It’s much more basic than that.

The point is that in order to experience what another individual experiences, we would need to be that other individual.

The following is the basic argument:

(i) If you or I were another individual, then you or I would know what is it like to experience what that other individual experiences.

(ii) It is logically impossible for an individual to be another individual.

(iii) Therefore it is logically impossible for you or I to know what it is like to experience what another individual experiences.

Flanagan provided a concrete example of this when he wrote the following:

“There is no incoherence in comprehending some theory that explains bat experiences without grasping exactly what bat experiences are like for bats. Indeed, the theory itself will explain why only bats grasp² their experiences.”

More generally:

“A theory of experience should not be expected to provide us with some sort of direct acquaintance with what the experiences it accounts are like for their owners.”

Here we have a distinction between a theory about a given experience (or type of experience) and actually being able to (as it were) experience that experience. Flanagan believes that naturalism provides such a theory. However, Flanagan also concedes that no individual can experience what another individual (whether a bat or another human person) experiences.

What’s more, Nagel’s position is both extreme and obvious.

It is so because Nagel advances the position (if only implicitly and tangentially) that if a given individual can’t literally become another individual, then any theory of that other individual's experiences (or, indeed, of any experiences) will always fail. Or as Flanagan put this point:

“The horn is easily avoided by seeing that its source lies in the unreasonable expectation that grasping a theory (grasp¹) should ‘open’ the experiences to us (grasp²). If we don’t grasp² bat experiences once we grasp¹ the theory that explains bat experiences, then we don’t really understand (grasp¹) the theory.”

Owen Flanagan’s Naturalism

It’s ironic that naturalism “can explain why only you can capture what it is like to be you”. That is, naturalism can explain why only you can know what it’s like to be you. However, naturalism can’t also enable the naturalist to experience what it is like to be you. And that’s because, again, “your sensory receptors and brain are properly hooked up to each other” and not properly hooked up to the naturalist or scientist studying you.

So Flanagan freely and happily admitted that “your experiences are yours alone”. And then he offered more detail when he argued that “you are in the right causal position to know what they seem like”. Flanagan even acknowledged that

“nothing could be be more important with respect to how your life seems and to how things go for you overall”.

And yet! -

“[N]othing could be less consequential with respect to the overall fate of the naturalistic picture of things.”

So, again, apart from stating the obvious point that you (or anyone else) can’t be another individual, Flanagan also noted that this fact has almost zero consequence or relevance for either science or for naturalism.

But what about physicalism?

Physicalism?

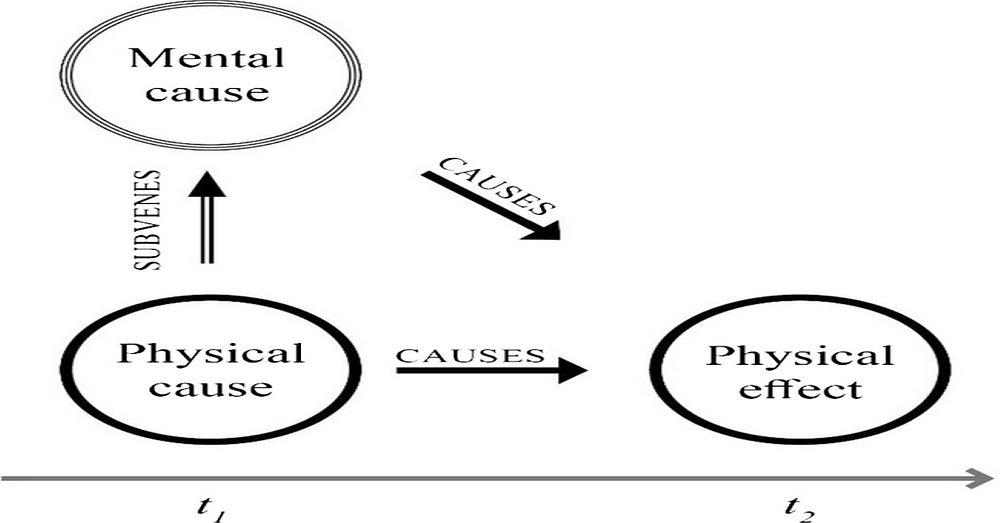

Basically, Flanagan argued that the language of physics (or indeed any scientific language) can’t be used to describe experiences from a first-person perspective. That’s mainly because physics doesn’t even attempt to describe perspectives and experiences from a first-person point of view. Instead, physics (along with the other sciences) attempts to describe and/or explain first-person perspectives and experiences form a third-person point of view. (Daniel Dennett has had much to say on this in that he completely accepts what he calls heterophenomenology.)

In fact Flanagan widens this general point out by arguing that “everything physical” cannot be “expressed or captured in the languages of the basic sciences” (i.e., in the languages of “completed physics, chemistry, and neurophysiology”). In basic terms, then, that’s because even though first-person experiences and perspectives are indeed physically “realised” in the brain, they still can’t by “captured”, expressed or described in the languages of the basic sciences.

The position just expressed above is pitted against what Flanagan calls “linguistic physicalism”.

All this means that we have two positions which may, at least at first, seem to contradict one another:

(1) Flanagan wrote: “All there is, is physical stuff and its relations.”

(2) Flanagan believes that not all physical stuff can be “captured in the languages of the basic sciences”.

Again, statement (1) is accepted primarily because even an individual’s experiences and perspectives are “realised” in physical stuff (in this case, the brain). Yet statement (2) tells us (if implicitly) that aspects of the brain are experienced from first-person “modes of presentation”.

In more concrete and specific terms, Flanagan continued:

“‘An experience of red’ is not in the language of physics. But an experience of red is a physical event in a suitably hooked-up system. Therefore, the experience is not a problem for metaphysical physicalism.”

Yet Flanagan happily acknowledges that

“no linguistic description will completely capture what a first-person experience of red is like”.

And that’s largely because physics — or the sciences generally — can’t get around the logical truth that x can never be y.

***************************

Notes on Qualia

(1) Even Daniel Dennett accepts that qualia are “real”… Or at least Flanagan believed that Dennett does when he wrote the following:

“Qualia are for real. Dennett himself says what they are before he starts quining. Sanely, he writes, ‘‘Qualia’ is an unfamiliar terms for something that could not be more familiar to each of us: the ways thing seem to us’ [].”

… But so what?

Sure — there are ways things seem to us. Okay. But where do we go from there?

Dennett may well accept qualia. However, he certainly doesn’t accept what he takes to be the one and only philosophical account of them — see here. (Incidentally, Owen Flanagan doesn’t believe that we need accept that one-and-only account.) That is, such qualia (at least on Dennett’s philosophical position) are mere “quicksilver” with very little scientific (or even philosophical) point.

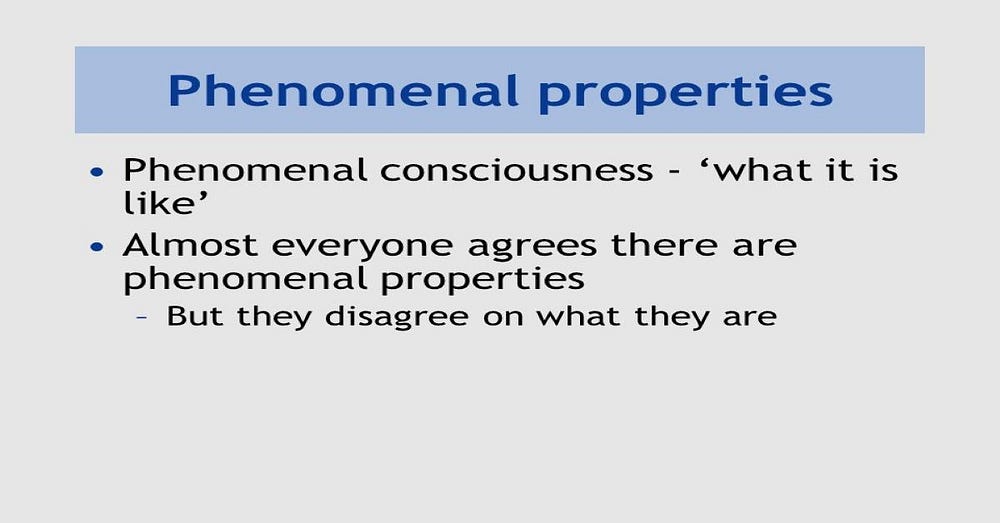

(2) One definition of the technical term “qualia” is that it captures (to use Dennett’s words as used directly above) “the ways things seem to us”. But that definition can’t be right. Qualia are supposed to capture the ways things seem to each individual. So there is no collective quale and therefore no “us” when it comes to an individual quale. Thus the definition of qualia should be: The way things seem for each individual. In that sense, a quale of, say, red, at time t for subject S will be different to a quale of red at time t² for that very same subject S. Thus there isn’t even a single static seeming to any single quale for any given individual subject.

In that sense, then, the particularities of the (possibly) infinite numbers of qualia may even work against the strong anti-physicalist positions of qualiaophiles.