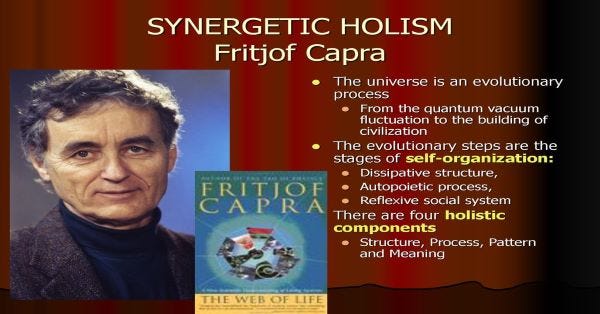

Physicist, best-selling author and “deep ecologist” Fritjof Capra believes that Western ways of thinking and behaving have “brought political disorder; an ever-rising wave of violence and an ugly, polluted environment”. He offers his solution to all that. That solution is a fusion of quantum mechanics (actually, specific interpretations of QM) and Capra’s own political and religious (“Eastern”) views.

“In our Western culture [] many have turned to Eastern ways of liberation.”

— From Fritjof Capra’s The Tao of Physics (see passage here).

The fact that some (or even many) self-described “spiritual” people embrace quantum mechanics (actually, specific interpretations of QM) for exclusively spiritual reasons is (almost) true by definition.

However, their drawing political conclusions from quantum mechanics isn’t really obvious at all.

So why stress this physics-politics link?

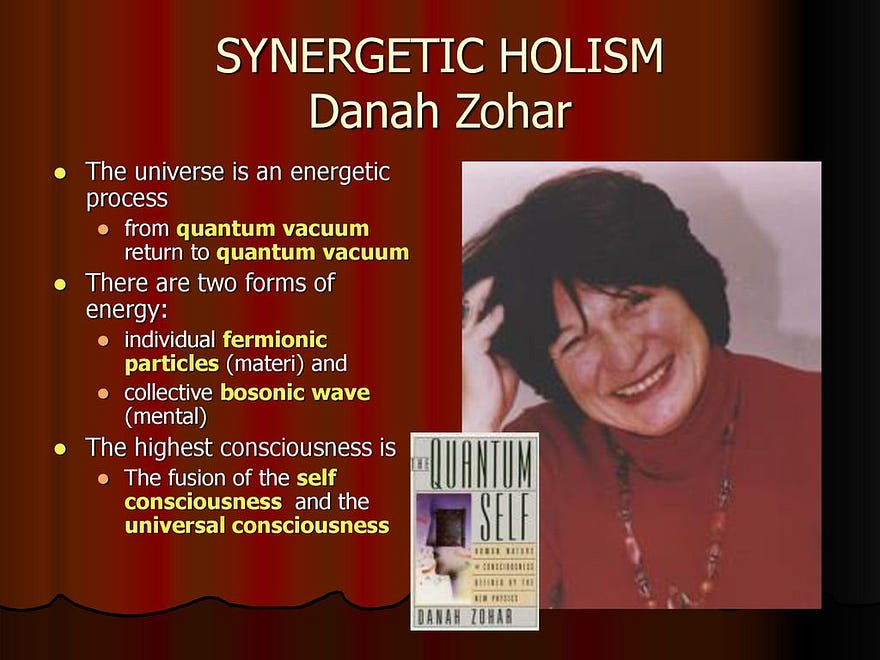

It’s stressed primarily because physicist Fritjof Capra himself stresses it. That is, Capra is open (as is Danah Zohar and others) about this link— as the quotes in this essay will clearly show.

Oddly enough (or perhaps not), Capra admits that most — perhaps even all (i.e., by definition!) — New Agers, spiritualists, etc. are anti-science.

That said, some (i.e., a small number) of those otherwise anti-science New Agers are nonetheless happy with quantum science. More accurately, such people are happy with those particular interpretations of quantum mechanics which can be used to back up their prior spiritual views.

Anti-Science and The Tao of Physics

One of Fritjof Capra’s main themes is that he isn’t himself anti-science at all.

Indeed (as the subtext often goes), how can he be? After all, Capra is a scientist himself.

Capra tells us that spiritualists and other New Agers, on the other hand,

“tend to see science, and physics in particular, as an unimaginative, narrow-minded discipline which is responsible for all the evils of modern technology”.

Thus, Capra wants to save science from itself at the same time as bringing “spiritual people” on board his “spiritual science” boat (see here)…

But first of all, such people must fully embrace Capra’s very own scientific-political-religious worldview.

So the following often-quoted passage (from Capra) may make things much clearer:

“Science does not need mysticism and mysticism does not need science, but man needs both.”

It was just said that Capra is not anti-science.

However, Capra (as with Danah Zohar) is certainly against “Newtonian science”. He spends much time telling us so. Indeed Capra may not even be a (as it were) unqualified fan of quantum physics. That is, he has little to say about quantum physics (at least in his best-selling books) as it can be presented completely divorced from all the political, spiritual, ecological, sociological, psychological, historical, etc. interpretations which he indulges in. Indeed, even the technical sections of Capra’s The Tao of Physics, for example, read like mere preludes to what he clearly sees as his own far more important political and spiritual interpretations. (Those interpretations which inevitably follow all that prior data on actual quantum mechanics.)

So (again, just like Danah Zohar), quantum physics became a tool which Capra used to advance his spiritual-political worldview.

In actual fact, Capra was very clear about his prime motivation for writing his best-selling book, The Tao of Physics. For example, he wrote:

“My starting point for this exploration — the threat of nuclear war, the devastation of our natural environment, our inability to deal with poverty and starvation around the world…”

The “worldview” Capra is fighting against is “inadequate for dealing with the problems of our overpopulated, globally interconnected world”.

His own worldview (or political religion) is, of course, the answer or solution.

But there’s one thing that needs to be got straight out of the way:

What about Capra’s actual physics?

Fritjof Capra’s Physics

The best way to tackle the relation of actual quantum physics to Fritjof Capra’s politics is to quote Capra himself thus:

“[] I am very pleased that in all the criticism I have had from fellow physicists, not one of them has found any fault in my presentation of the concepts of modern physics. [] to the best of my knowledge nobody has found any factual errors in The Tao of Physics.”

This is odd.

I don’t believe that many — or even any — of the physicists (as well as many others) who’ve criticised Capra ever claimed that he got the quantum physics wrong. (At least not in a way that is relevant.) That’s because their criticisms usually had — and still have — nothing to do with Capra’s (to use his own words) “factual errors” or his “presentation of the concepts of modern physics”. (This may depend on how he presents each particular concept and theory of quantum physics and physics generally.) The criticisms were primarily to do with how Capra extrapolated from physics to a whole host of political, sociological, spiritual, historical, psychological, ecological, etc. conclusions and interpretations.

Thus, even if Capra’s physics is perfect in every single detail (or at least his presentations of other people’s physics is perfect), then that would still be irrelevant to the issue at hand here: Capra’s political interpretations and uses of the actual physics.

All this is also the case when it comes to Danah Zohar.

Her actual physics — and, in her case, also her neuroscience and biology — may well be faultless too. However, that simply doesn’t matter here.

[Danah Zohar’s neuroscience and her interpretations of it are almost entirely down to (as she more or less admits) four papers her husband — Dr I.N. Marshall — wrote, all of which strongly emphasise the role of Bose-Einstein condensates when it comes to consciousness.]

This situation, then, is a little like quantum mechanics and its many and varied interpretations. That is, most interpreters agree on the quantum theory, mathematical formalism/s, the mathematics generally, the experiments, the predictive results, etc. However, they interpret what metaphysically underlies all that in different — sometimes very different — ways.

In fact, Capra knows full well what the problem is.

Capra does so because he too makes a (to use his own words) “distinction between the mathematical framework of a theory and its verbal interpretation”. And then he continued:

“The mathematical framework of quantum theory has passed countless successful tests and is now universally accepted as a consistent and accurate description of all atomic phenomena. The verbal interpretation, on the other hand — i.e., the metaphysics of quantum theory — is on far less solid ground.”

All that said, other important and well-known interpretations of quantum mechanics never include references to politics, spirituality, sociology, history, ecology, “Eastern thought”, etc. So, in that sense, Capra is going much further than any other accepted interpretation of quantum mechanics. (This is even true of David Bohm, who, arguably, never went as far as Capra.)

Fritjof Capra’s Politics

Fritjof Capra’s political, spiritual and Eastern-centric (Capra himself often uses the word “Eastern”) account of the West’s many faults are captured in his following words:

“The natural environment is treated as if it consisted of separate parts to be exploited by different interest groups. The fragmented view is further extended to society which is split into different nations, races, religious and political groups.”

This Western way of thinking and behaving leads to Capra’s End Times and hyperbolic conclusion:

“The belief that all these fragments — in ourselves, in our environment and in our society — are really separate can be seen as the essential reason for the present series of social, ecological and cultural crises. It has alienated us from nature and from our fellow human beings. In has brought a grossly unjust distribution of natural resources creating economic and political disorder; an ever rising wave of violence, both spontaneous and institutionalized, and an ugly, polluted environment in which life has often become physically and mentally unhealthy.”

These words from Capra’s own pulpit (which are very Biblical in both content and tone) would be deemed racist if they were said by a white person about any non-white (or non-Western) culture or group.

For example, many would pick up on what they’d call its stereotypes, crude simplifications, vagueness, rhetoric, exaggerations, loaded philosophical interpretations, etc. Indeed, Capra’s words are an example of classic Occidentalism.

So perhaps the cultural critic Edward Said (who died in 2003) would have classed Capra’s views as a perfect example of positive — i.e., not negative — Orientalism. (Or at least Said should have done so had he been made aware of Capra’s work.) In other words, Occidentalism and Orientalism have often occurred together. And Capra’s own words are a good example of that fusion.

[China has roughly 254,700,000 Buddhists - so is China a deeply ecological and non-patriarchal society? What about Japan, Thailand, North Korea, Nepal and South Korea? Are they New Age, Green and spiritual utopias?]

As already stated, Capra is open about his politics-spirituality fusion. For example, he wrote:

“[S]pirituality corresponding to the new vision of reality I have been outlining here is likely to be an ecological, earth-centred, post-patriarchal spirituality.”

Here, spirituality is clearly fused with politics. Of course Capra could say that “the spiritual is the political”. After all, political activists, feminists, etc. in the 1960s and beyond said that “the personal is the political”. So that would be fair enough. And at least that would place Capra’s position out in politically open fields.

Capra is even clearer about his spirituality-politics fusion when he says that the “rising concern with ecology” has paralleled the “strong interest in mysticism”.

Yet all interest in mysticism — and even in ecology — won’t necessarily lead in the same political direction. Moreover, it definitely won’t lead (i.e., of necessity) in the very precise political directions which Capra himself strongly desires — as the Nazi movement of the 1920s and 1930s graphically shows.

So let’s take a short detour here.

Many National Socialists (i.e., Nazis) in the 1920s and 1930s were keen ecologists, believers in “animal rights”, and deeply influenced by certain mystical and spiritual traditions. So it’s ironic that much has been made of the Christianity-Nazi link by various people. The Nazi-mysticism/spirituality link, on the other hand, is rather understressed or even completely ignored.

[See ‘Examining Nazi Environmentalism During Earth Week’, ‘Animal welfare in Nazi Germany’, ‘How Mysticism and Pseudoscience Became Central to Nazism’, and the chapter ‘Lucifer’s Court: Ario-Germanic Paganism, Indo-Aryan Spirituality, and the Nazi Search for Alternative Religions’.])

To return to Capra’s own politics.

Capra became even more open when he cited the following silly binary option of moving “to the Buddha or to the Bomb”. (The former is “the path of the heart”.)

So If we choose the Buddha, then we’ll essentially choose Capra’s very own political-spiritual/religious worldview. But if we choose the (Platonic) Bomb, then we’re all, well, typical “Westerners”.

Thomas Kuhn and Capra’s Political Activities

Capra is clear that he wants to create a new (to use his word) “worldview” (i.e., a spiritual-political religion). However, he sometimes uses the word “paradigm” instead. Capra uses the word “paradigm” primarily because he’s been influenced by the philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn.

In his book Belonging to the Universe, Capra refers to Kuhn’s own well-known book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Thus, Capra uses Kuhn’s ideas as a basis for his own Kuhn-like “revolution”, as well as for the creation of his own paradigm. That paradigm is a fusion of science, politics and religion. Or, more accurately, it’s a fusion of Capra’s very own religious and political views and only certain interpretations of quantum mechanics.

So Capra’s demands are far from modest.

In the books Belonging to the Universe and The Tao of Physics, Capra demands that Western culture reject what he calls “linear thought” (see here) and the “mechanistic views” (see here) of Newton and Descartes. Predictably, he’s against reductionism too. (See ‘Hang the Reductionists’, which is the New Scientist’s account of Capra’s position on reductionism.)

Indeed, apart from his best-selling books, lecture tours, seminars, educational courses (one of which is dedicated entirely to his own worldview — see Capra Course), etc., Capra has a few other means to bring forth his political-spiritual vision.

For example, Capra is a founding director of the Center for Ecoliteracy in California. This organisation “promotes ecology” and is involved with educating American schoolkids and students. Another political string to Capra’s bow is being a member of the Earth Charter International Council. The idea of the Earth Charter began with Maurice Strong and is strongly connected to both The Club of Rome and the United Nations.

So, as already stated, Fritjof Capra’s political demands are far from modest.

******************************

Notes:

(1) On a psychological reading, perhaps Fritjof Capra is rebelling against the West as a teenager fiercely rebels against his father. Indeed Capra’s Occidentalism has a long tradition among largely upper-middle-class Western men, dating back to the explorer and writer Richard Burton in the 19th century and even before that. Today we also have the very-privileged examples of George Monbiot, Jonathon Porritt and many more of this ilk. There’s probably also a very strong element of upper-middle-class “guilt” — or even “white guilt” — here too.

(2) The quantum physicist Pascual Jordan (1902–1980) at one point interpreted biology through a Nazi lens. Take this passage:

“We know that there are in a bacterium, among the enormous number of molecules constituting this … creature … a very small number of special molecules endowed with dictatorial authority over the total organism; they form a Steuerungszentrum [steering centre] of the living cell. Absorption of a light quantum anywhere outside of this Steuerungszentrum can kill the cell just as little as a great nation can be annihilated by the killing of a single soldier. But absorption of a light quantum in the Steuerungszentrum of the cell can bring the entire organism to death and dissolution — similar to the way a successfully executed assault against a leading [führenden] statesman can set an entire nature into a profound process of dissolution.”

That’s the thing about the interpretations of quantum mechanics — they can be innumerable and infinitely variable.

My flickr account: