Schrödinger’s cat is a reductio ad absurdum. So too is Wigner’s friend. Both are related examples of thought experiments which were (as it were) designed to show how and why a particular position (or theory) is absurd.

Schrödinger on the Collapse of the Wavefunction

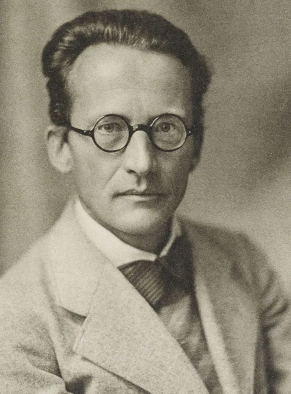

The Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger (1887–1961) pointed out something which has now become commonplace: that there’s nothing in the (or a) wavefunction itself about (its own) collapse.

Way back in 1927, it was Werner Heisenberg who first used this idea to explain why physicists only find a single (to use Schrödinger’s own word) “alternative” at the end of an experiment. In other words, experimenters never observe a quantum superposition of alternatives states.

Yet Schrödinger himself reacted against Heisenberg’s notion of the collapse of the wave function by what the former called “the observer”.

In a paper published in 1952 (‘Are There Quantum Jumps?’), Schrödinger went further when he stated that it’s “patently absurd” that the wave function should

“be controlled in two entirely different ways, at times by the wave equation, but occasionally by direct interference of the observer, not controlled by the wave equation”.

From this passage alone, it can be seen that there’s a strong hint at the issue which the Wigner’s Friend thought experiment itself tackles. (This is particularly true of the clause, “the observer [is] not controlled by the wave equation”.)

To explain.

The physicist has the option of collapsing the wave function. And only then is the possibility (or reality) of so many mutually-contradictory alternatives existing together no longer a problem. In other words, the collapse (as it were) brings to an end all those alternatives existing together…

Except that this issue isn’t really solved at all — at least not philosophically.

That’s simply because we’ve moved away from one problematic situation (i.e., the wavefunction’s many alternatives existing together before its collapse), to another problematic situation (i.e., the actual collapse of the wavefunction into a single state).

To state the obvious: there wouldn’t even be any “collapse of the wavefunction” if there wasn’t a previous wave function which (as it were) needed to be collapsed.

Yet on Schrödinger’s (possibly?) “lunatic” multiple-alternatives version, the wavefunction isn’t collapsed at all. Instead, one single (in this case at least) cat must be both dead and alive.

Schrödinger’s Many Worlds?

It must be stressed here that Schrödinger certainly didn’t put any of the above in the way I’ve just done. Instead, he simply raised the possibility that all the wavefunction’s alternatives happen simultaneously (i.e., if seen only in accordance with the mathematics of the wavefunction itself). And this, then, must also be true of all the quantum objects which are part of (or described by) each wavefunction. [See my ‘Erwin Schrödinger on the Many Worlds of the Wave Function’.]

Schrödinger gets (to use the cliche) weirder.

He actually said that all the probabilities in the wavefunction

“may not be alternatives [ ] but all really happen simultaneously”.

Well, according to the wavefunction, they actually do all happen simultaneously…

Or do they?

It depends.

In any case, the issue here can be summed up technically and philosophically by saying that the mathematical probabilities (or ‘probability amplitudes’) of the wavefunction are effectively concretised (or reified) by quantum interpreters when they assign physical phenomena to “what the maths says”.

Alternatively, perhaps it can be said that the wavefunction itself concretises all (as it were) its probabilities (or Schrödinger’s “alternatives”).

To repeat.

It can basically — as well as accurately — be said that with the wavefunction, there are actually many alternatives happening simultaneously. Thus, such (supposed) “weirdness” is entirely a product of the wavefunction itself.

In broader terms, then, the quantum theorist (or interpreter) has no right to say that these many alternatives do not all occur together. In other words, if a theorist shouldn't really say anything about an unobserved realm (or a realm beyond the wavefunction), then what right has he to say that such alternatives don’t all occur together? After all, the wave function is (as it’s put) telling him that they do all occur together.

Thus, in order to demonstrate that these alternatives aren’t really happening simultaneously, a quantum theorist would need to move beyond the maths, and enter the weird and mysterious world of… interpretation.

In other words, the quantum theorist would need to offer an interpretation of all the mathematics.

To change tack a little.

The title of this essay is ‘Does ‘Wigner’s Friend’ Support Consciousness-First Physics?’. So there’s a reference to consciousness in that title.

Schrödinger’s Scientific Realism

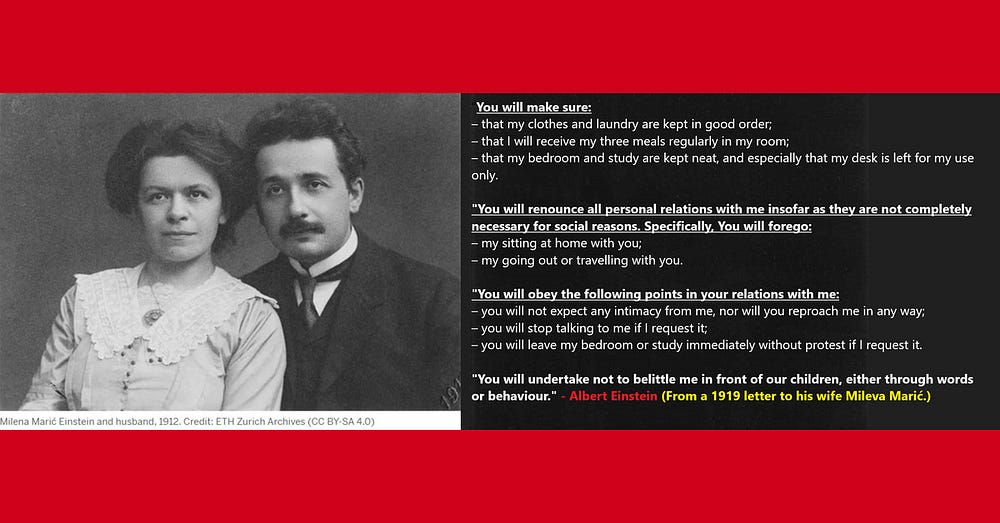

Despite the fact that many idealists, New Agers and spiritual commentators recruit Schrödinger into their various causes (see here, and their stress on Schrödinger’s “anti-materialism”), it’s clear that, as far as quantum mechanics itself is concerned, he wasn’t an idealist. Indeed, it’s also tempting to say that Schrödinger was the exact opposite of an idealist. (If that way of putting things even makes sense.)…

But, sure, in Schrödinger’s private and non-scientific life, perhaps he was an idealist, as well as a “spiritual person”.

In any case, let’s go into more detail on this.

In basic terms, Schrödinger had a problem with the stress on consciousness (or simply on observation) in the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics. That was because he argued that the collapse of the wave function (as already stated) is as weird (or even weirder) than the content of the wavefunction itself…

Was Schrödinger right?

Think about this story.

The wavefunction — as well as what it “describes”?- is a certain way, and then a (mere) observation stops it from being that certain way.

So can we now conclude that if this is truly the case, then such an observation literally changes reality. (This is the case without the observation or experimenter having any physical impact on the experimental setup.)

All this means that Schrödinger certainly played down the role of consciousness in quantum mechanics. (That’s despite what Schrödinger’s idealist and spiritual quoters and fans claim or merely hint at. See note 1.)

So it can — easily? — be argued that Schrödinger was a realist. [See ‘Scientific realism’.]

Alternatively, and in purely philosophical terms, Schrödinger appears to have been a metaphysical realist — at least on this precise subject. [See ‘Metaphysical realism’ and ‘Philosophical realism’.]

To explain Schrödinger’s scientific realism some more.

Schrödinger claimed that nature (or the world) was a certain determinate way before any act of observation.

Granted that in this account it’s essentially the wavefunction (or, to use Schrödinger’s own words, “what [the wave function] says”) which is real. Yet the wavefunction is, after all, supposedly telling is something about the world. Thus, in this instance at least, there are (or were) multiple (mutually contradictory) alternatives happening simultaneously!

So can all this be solved by arguing that there’s a dead cat in our universe, and an alive cat (its counterpart) in another universe?

Let’s now move on from Erwin Schrödinger to Hugh Everett and his “many worlds theory”.

Hugh Everett’s Many Worlds, and Wigner’s Friend

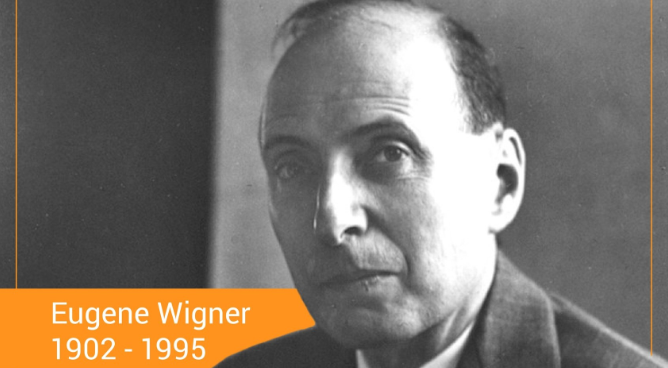

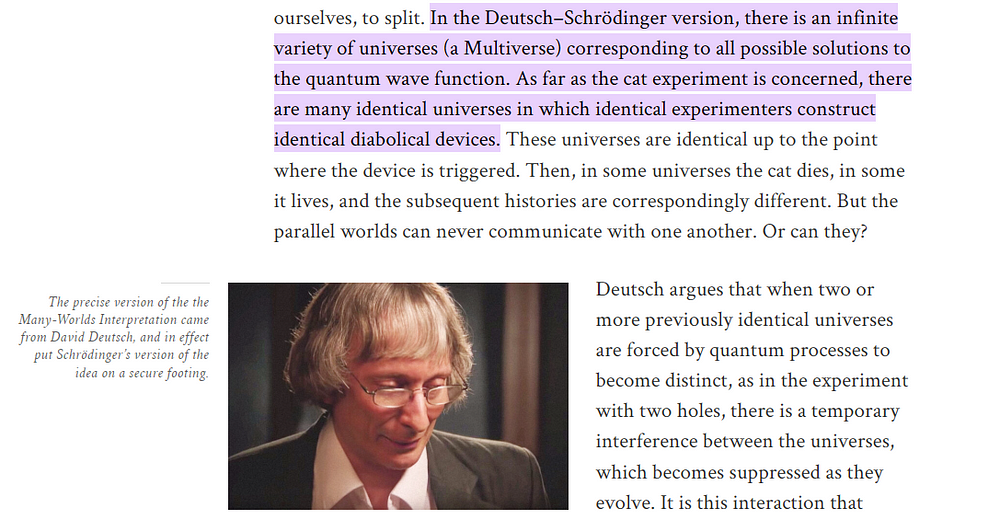

In the foundational many-worlds text ‘“Relative state” formulation of quantum mechanics’ (1957), Hugh Everett III actually mentioned what he called the “amusing, but extremely hypothetical drama” that is Wigner’s Friend thought experiment.

Oddly enough, researchers later found that in an early draft (i.e., earlier than 1957) of this doctoral thesis, Everett discussed the Wigner’s Friend thought experiment — without mentioning either Wigner or the words “Wigner’s friend”! In other words, this idea was in Everett’s mind years before Wigner’s 1961/67 paper, ‘Remarks on the mind-body question’.

In any case, Everett was a student of Wigner. So this means that they must have discussed the Wigner’s Friend scenario together at some point.

Anyway, that’s the history, what about the many-worlds theory itself?

In the many-worlds theory (as hinted at earlier), we can make sense of everything Schrödinger said earlier by bringing in other “worlds”. That is, if we bring in another world, then one cat is alive in that world, and another cat (its counterpart) is dead in our own world (or vice versa).

In other words, when the box is opened, we find only a dead cat. And that box-opening is equivalent to an observation (or the collapse) of the wavefunction.

So did Hugh Everett and Eugene Wigner actually differ on this issue?

Wigner believed that the consciousness of an observer is responsible for the collapse of the wavefunction (i.e., regardless of any refences to anyone’s “friend”, etc.). Everett, on the other hand, stressed the objectivity and non-perspectival aspects of his many-worlds theory.

What’s more, Everett claimed to have solved the Wigner’s friend “paradox” by bringing in different worlds.

It must now be said that Wigner himself didn’t believe that a conscious observer can also be in a state of superposition. However, he did acknowledge that this is the end result (i.e., a reductio ad absurdum) of his own thought experiment. Indeed, that was his thought experiment’s central point.

Wigner’s actual position, however, was that the wavefunction had already been collapsed when his “friend” observed the cat (or when he observed any given quantum system).

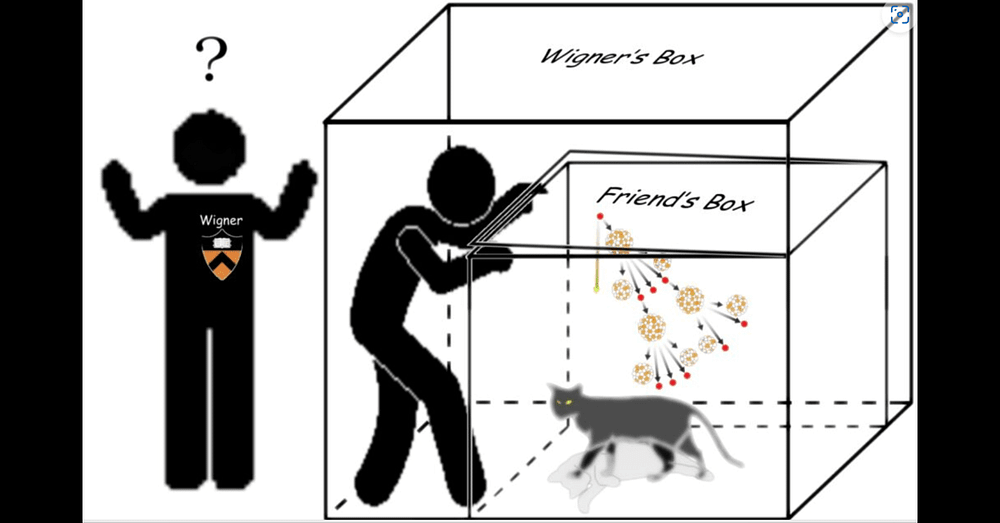

Now if we relate all this specifically to the Wigner’s Friend scenario.

Some Technical Details

Wigner’s friend measures, say, the spin of an electron (or the life-status of a cat). This results in a branching of the (or our) world into two parallel worlds. In one world, Wigner’s friend has measured the spin to be 1 (or the cat to be alive). At another world, the very same friend (i.e., Wigner’s friend) obtains the measurement outcome 0 (or the cat being dead).

So what about Wigner and his friend when taken together as a joint (quantum) system?

When Wigner himself measures the combined system of his friend (qua system) and the electron-spin-system (or cat-system), then that system splits again into two parallel worlds.

Now let’s sum up Wigner’s Friend again.

If I collapse the wave function of, say, an electron (or a cat), then my friend has to observe me collapsing (or offering him information about) the electron’s (or cat’s) wave function. More relevantly, my friend needs to collapse the wavefunction that is myself collapsing the electron’s (or cat’s) wavefunction…

This is where it gets bizarre.

If this is the case, then, a friend of my friend will need to observe my own friend in order to collapse his wavefunction, which is actually now my friend+myself+an electron (or a cat). In other words, my friend’s friend is collapsing the wavefunction which is my friend collapsing the electron’s (or cat’s) wavefunction, and that wavefunction includes myself collapsing the electron’s (or cat’s) wavefunction. And so on…

The theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli puts all the above in both a technical and a philosophical way.

Carlo Rovelli on Wigner’s Friend

In Carlo Rovelli’s philosophical system, we have what he calls an “observer system” O (which he sees as an epistemic system), which interacts with a quantum system S (which he sees as an ontological system). [See Rovelli’s ‘Relational quantum mechanics’.]

We therefore need to take into account the fact that there are (or at least there can be) different accounts of the very same quantum system. (This is a variation on the notion of the “underdetermination of theory by evidence”.)

In more technical detail on the wavefunction and its alternatives.

System S is in a superposition of two or more states.

A theorist or experimenter can “collapse” this system to achieve an “eigenstate”, which is both determinate and circumscribed.

All this means that if we have two or more interpretations of system S, then what scientists call “observers” must have been brought into the story. And that also means that there must be additional relations (or what Rovelli calls “interactions”) to consider between system S itself, and things outside S.

In terms specifically of Wigner’s Friend.

This also means (or at least it can mean) that we need a second observer (O’) to observe the observer-system (O), who (or which), in turn, has observed (or is observing) quantum system S.

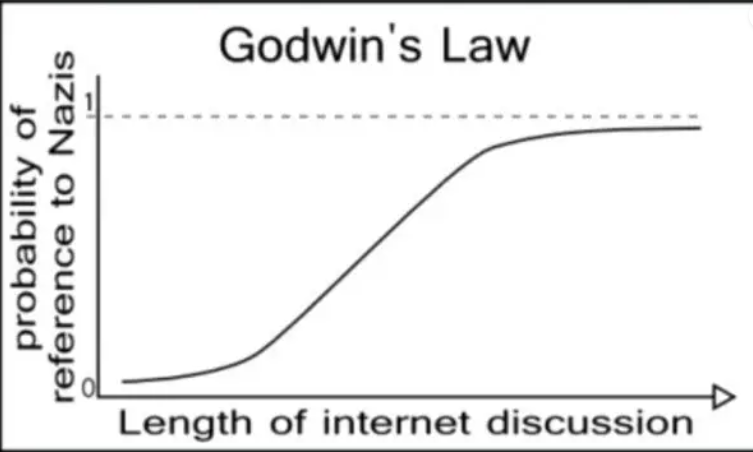

All this multiplies relations (or interactions) indefinitely.

Indeed, perhaps we even have some kind of infinite regress on our hands here.

Now another important part of this story needs to be told.

In simple terms, consciousness-first theorists dispute the idea that an instrument can, on its own, collapse the wavefunction.

Michio Kaku picks up on this debate.

Michio Kaku on Observers vs Cameras

The physicist Michio Kaku tackles this issue in terms of the specific case of human observers vs cameras.

“Some people, who dislike introducing consciousness into physics, claim that a camera can make an observation of an electron, hence wave functions can collapse without resorting to conscious beings.”

Prima facie, even the phrase “a camera can make an observation of an electron” seems odd. Indeed, it seems anthropomorphic to claim that a camera— alone! — can observe anything.

Isn’t it the case that human beings use cameras in order to observe things?

However, perhaps this is just a semantic issue. [See note 2.]

In any case, Kaku then raises the following problem:

“But then who is to say if the camera exists? Another camera is necessary to ‘observe’ the first camera and collapse its wave function. Then a second camera is necessary to observe the first camera, and a third camera to observe the second camera, ad infinitum.”

This is a (as it were) concrete example of the problem of Wigner’s Friend.

Firstly, Kaku’s words are about a camera which is supposed to observe a cat (or a quantum system) all on its own. Kaku also seems to be bringing up the issue of this camera’s very existence as it was before it too was observed. Or, at the very least, Kaku brings up the issue of the camera’s wavefunction itself being required in order for the cameras to (as it were) exist!

Is this an anti-realist (if not idealist) point about the very nature and role of so-far unobserved (as it were) noumena?

All that said, isn’t it the case that Kaku’s camera still registered something regardless of any minds that later made sense of (or interpreted) that registration? (Schrödinger, again, talked in terms of minds “giv[ing] it meaning”.)

Some readers may question about the word “registered”. (I quibbled earlier about the word “observed” when it came to Kaku’s camera observing all on its own.)

In this case at least, all “registered” means is the following:

Prior to observation, something left some kind of physical imprint on the camera.

Yet it’s still the case that what the camera supposedly registered (or “observed”) may not have any role to play until what it registered (or observed) is also registered (or observed) by another camera. More relevantly, what the camera registered (or observed) may not have any role to play until it too is interpreted by an actual human mind.

Notes:

(1) Idealists, New Agers, and spiritual commentators conflate Schrödinger’s (mitigated) anti-materialism with an equal stress on the prime importance of consciousness. Schrödinger may well have been an anti-materialist in some ways. However, he certainly didn’t place consciousness at the forefront of his physics.

(2) Scientists can use old terms in completely new ways. True. Yet it also depends on others knowing that, as well as on whether or not scientists actually are using old terms in new ways.