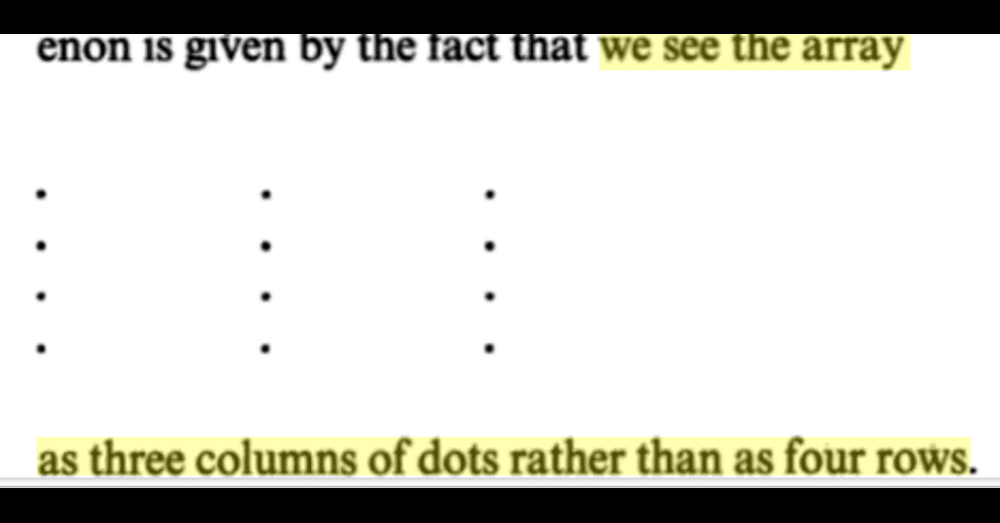

The conceptual nature of experience (as derived from sensations) is supposedly shown by an example from the philosopher Christopher Peacocke, as seen in the main image above.

This suggest that concepts (of columns, in this instance) are determining our experiences.

Readers may immediately suspect that there must be at least some people who do indeed see four rows, rather than three columns. In other words, there’s no obvious reason why we shouldn’t see four rows.

This may also have something to do with the spacing of the dots, and the wideness of the gaps between the columns. Thus, the gap between the columns is wider than the gap between the individual dots. This may lead most viewers to see three columns, rather than four rows.

Christopher Peacocke’s point, however, is that the sensations alone don’t determine the experience. Indeed, on this picture, if it were just a question of sensations alone, then it wouldn’t actually be an experience. (Experience is often said to be “under an aspect”.)

The same applies to another example from Peacocke.

One person may see the object which we call a “sphere”, though not (as it were?) apply the concept [sphere] to it. Another person will indeed apply the concept [sphere] to that very same object.

On the other hand, and more likely, most people won’t actually apply the concept at all. That is, the concept will belong to the object from the beginning. In other words, many subjects non-cognitively experience a sphere as a sphere. A person without the concept [sphere], on the other hand, will still either apply a concept to the sphere, or a concept will belong to the sphere.

In the technical details of contemporary analytic philosophy.

Peacocke himself says that “sensational properties do not determine representational content”. On this picture, then, concepts must be part of the story too.

Peacocke does go on to say that “grouping properties [i.e., the arrays into columns not rows] are sensational rather than representational”. Peacocke admits that the array example

“seems to suggest that we are concerned with representational, not a sensational, property: the concept of a column enters the content”.

The problem is (in Peacocke’s argument) that “grouping [is a] sensational property”. Surely grouping (in this example) will rely on sensations, although sensations alone won’t entirely determine the grouping. Thus, Peacocke is making a distinction here between grouping and sensations. Indeed, he’s saying that grouping isn’t conceptual (or “representational”).

On this particular aspect, Peacocke doesn’t go into detail. He does say, however, that in “switches of aspect the sensational properties [remain] constant”.

Martin Davies and Colin McGinn

The British philosopher Martin Davies spots a dualism in Christopher Peacocke’s position.

Davies says that (in Peacocke’s story) there’s

“a sensational (non-representational) substrate upon which the representational superstructure [] is erected” .

Or

>) Representational superstructure

>) Sensational (non-representational) substrate

As with Ned Block’s notions of “access-consciousness” and “phenomenal-consciousness”, Davies quite happily accepts “non-representational properties of experience”, but “without embracing the idea of a sensational substrate”.

The British philosopher Colin McGinn also characterises the position represented by philosophers like Peacocke. He states that they accept

“prerepresentational yet intrinsic level of description of experiences: that is, a level of description that is phenomenal yet noncontentful”.

Perhaps the problem is that Peacocke thinks in terms of “protopropositional content” — i.e., nonconceptual content. This is almost — or indeed literally — an acceptance that content prior to “propositional judgement” can’t be conceptual. In that case, then, propositions (almost literally?) must make (or determine) concepts. That is why protopropositional content is nonconceptual content. However, if we don’t accept an entirely linguistic basis for concepts, then we needn’t believe in Peacocke’s non-conceptual content.

Davies points out that Peacocke is happy to accept the conceptualisations of “sensational properties”. He says that Peacocke shows us examples of

“pairs of experience with the same sensational properties but different representational properties”.

Yet Peacocke also shows us

“pairs of experiences with the same representational properties but different sensational properties”.

Does all this show us that these “different sensational properties” are nonconceptual?

It seems to hint at the fact (or possibility) that sensational properties aren’t representing anything.

[The other cases cited by Peacocke are based on technical empirical psychological research on subjective experience, which is difficult to comment upon.]

Peacocke, however, appears to make a mistake. He says that a person

“waking up in an unfamiliar position or place [will have] minimal representational content”.

Mental or cognitive unfamiliarity doesn’t entail a lack of conceptual content. That’s because the person waking up will still conceptualise his unfamiliar position or place.

So perhaps this example only displays Peacocke’s linguistic (or propositional) bias.

Of course, the person waking up may not be able to describe the position or place very well, or form “propositional judgements” about it. However, that may be irrelevant to conceptual and/or representational content.

According to the British philosopher Michael Tye, when the place or position becomes “rich” with “representational content”, then this may simply be a case of applying “descriptive labels [] to the array”. Propositions and propositional judgements are simply additions to the conceptual content which already exists.

Tye also says that

“computational routines [propositional judgements] process this activity and assign an appropriate descriptive term”.

Some readers may believe that Peacocke’s propositional (or linguistic) bias causes problems for various of his positions. However, it can be doubted that Peacocke would actually deny his linguistic (or propositional) bias. To Peacocke, the bias itself wouldn’t cause problems in his eyes. It’s simply part of the reality of conceptual experience.

[The British philosopher Peter Geach was explicit about his propositional — or linguistic — bias vis-à-vis concepts and mental content. See his Mental Acts and Their objects, which was published in 1957.]

According to Michael Tye again, “phenomenal content” is by definition nonconceptual . And he too offers us us his own dualism between “phenomenal content” and belief. We have (a)

“A content is classified as phenomenal only if it is nonconceptual and poised [for use by the cognitive centres].”

against (b):

“Beliefs [] lie within the conceptual arena, rather than providing inputs to it.”

This is almost foundationalist in that “phenomenal content” is seen as input to be worked upon later (if only a split second later).

Beliefs, on the other hand, are outputs.

Indeed, if this is truly foundationalist, then a) above would be the Given.

It certainly seems foundationalist when Tye makes the epistemic point that phenomenal content is “poised for use by the cognitive centres”. That is, phenomenal content comes (epistemically) before such use.

Yet Tye makes the point that phenomenal content is still “representational”.

How can this be?

How can something represent “that there are such and such co-instantiated locational and nonlocational features” without concepts?

Note:

At least some of what has been said in the above will be relevant to the Rabbit–duck illusion, which was made popular by Ludwig Wittgenstein.