Many people (often non-academics) mention “peer-reviewed literature” at the drop of a hat. The main reason they do so is to back up — or give kudos to — their own positions.

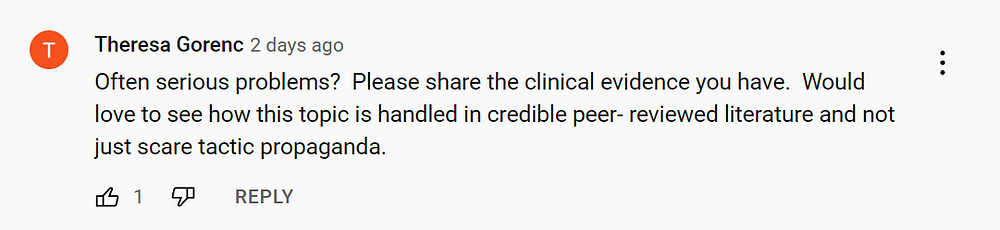

“I Would love to see how this topic is handled in credible peer-reviewed literature and not just scare tactic propaganda.”

— Theresa Gorenc (see screenshot at the end)

On social media (especially on political “discussion forums”) many people (often non-academics) mention “peer-reviewed literature” at the drop of a hat. The main reason they do so is to back up — or give kudos to — their own (non-peer-reviewed) positions. This is graphically shown by the fact that such people never cite any peer-reviewed literature that puts positions they disagree with or which directly contradicts their own carefully chosen peer-reviewed literature…

[See how often the words “peer-reviewed literature” are used here.]

As a result of all this, the adjective “peer-reviewed” has become an easy cliché for many people.

But now it’s worth stating that this isn’t an essay against peer reviews — despite the title. And neither does it state that everything about the peer-reviewing process is bad. Indeed there may well be a need for peer-reviewing processes. What’s more, without peer-reviewing processes it can be argued that all sorts of rubbish would end up being published…

True.

However, all sorts of utter rubbish is published as a result of various peer-reviewing processes too!

So there are three main positions advanced in the following:

(1) Not everything that is “peer-reviewed” offers the truth, is of good quality, is trustworthy, rigorous, etc.

(2) No one should simply assume that everything that’s peer-reviewed is sacrosanct.

(3) Citing peer-reviewed literature can often be a mindless and grandstanding way to back up positions that the citer holds anyway (i.e., what he or she believed long before finding any favourable peer-reviewed academic research).

What’s more, often the people I have in mind don’t usually cite specific papers or literature (peer-reviewed or otherwise) anyway. Such people simply like asking whether the positions (or arguments, evidence, data, etc.) they don’t like (or agree with) have been… peer-reviewed. Thus, in these cases, such people don’t even feel the need to cite any actual peer-reviewed stuff which contradicts positions (or views) they don’t like. To them, what’s important is that they can simply make the point that the positions they don’t like haven’t been…. peer-reviewed. And that’s usually enough for them.

But what does the term “peer-reviewed” actually mean (i.e., beyond its literal translation)?

In non-critical terms, a “scholarly peer review” is used to determine a paper’s suitability for publication.

Yet isn’t it the case that almost all — or even literally all — published academic papers have been… peer-reviewed? That is, isn’t it the case that in order for any paper to have been published in any academic journal, then it must have been peer-reviewed… by at least two or more academics?

Now there’s the problem that peer-reviewing may not amount to much anyway.

Problems With Peer Reviews

Various commentators have noted the fact that academics can easily produce their own journal on their very own specialised subject or area — no matter how arcane or specialised it is. And when such a journal is created, then this automatically generates an entire sequence of peer-reviewed papers. That is, these academics and their journals — and perhaps some academics from related journals — peer review each other in what amounts to an incestuous circle jerk or echo chamber.

One important point that outsiders or non-academics (if any outsiders even care about these things) may not be aware of it is that submitted papers are usually reviewed anonymously by “peers” who’re deemed to be “experts in the relevant field”.

The obvious question here is this: What on earth guarantees the impartiality of such anonymous reviews? For example, what if there simply aren’t enough experts to give a good review? Indeed what if there is only one or two experts in any given field? In this case, won’t the reviews merely reflect the views, tastes and biases of those all-too-human reviewers?

All this means the following two things. (1) That the reviewers don’t need to rationalise their decisions face-to-face. (2) That the academics or postgraduates who submit papers are said not to know who’ll review them. (It can be strongly doubted that this is always the case.)

As a response to all this, alternatives have been suggested and even put into practice. For example, there’s such a thing as an open peer review. In this case, the reviewers’ comments can be seen by the readers of these academic publications. What’s more, often the identities of the reviewers are disclosed.

As stated a moment ago, various academics themselves have written critical papers on the peer-reviewing situation.

Self-Reference

Such academics have noted that it’s (fairly) easy to create a journal. They’ve also noted that peer-reviewing may be problematic even in cases of established and respected (but respected by which people?) journals.

Of course this creates a self-referential problem.

The academics who discuss the problems with the peer-reviewing process may themselves have been peer-reviewed and therefore involved at least some of the same scenarios. Yet this possibility depends on how many of these critical academics also use the term “peer-reviewed literature” as an easy, empty and bombastic means to bolster their own work and/or positions.

In addition, some of these criticisms of the peer-review process are themselves a little incestuous in that they aren’t of much interest to anyone who isn’t focussed on the minutia of forging an academic career.

But let’s just cite one example of self-reference, as found in the paper ‘Arbitrariness in the peer review process’.

You can tell that this is written by academics because of the gratuitous and almost pointless introduction of the word homophily. Indeed this paper itself self-referentially cites peer-reviewed papers which are critical of the peer-reviewing process. So perhaps this can be taken to hint at peer-reviewing being a “self-correcting process”… except for the fact that the vast majority of academics will neither have read these critical papers or even care about their findings.

Anyway, take this typical passage of pure academese:

“Lately, many studies have emphasized the problems inherent to the process of peer review (for a summary, see Squazzoni et al. 2017). Moreover, Ragone et al. (2013) have shown that there is a low correlation between peer review outcome and the future impact measured by citations.Footnote1.”

Now for a few more words on these (as it were) papers on papers.

More Problems with Peer-Reviewing Processes

Many studies (we need to quiz that term too) have noted the many problems with academic peer-review processes.

For example, it’s been shown that just because some paper has been peer-reviewed, that doesn’t automatically mean that this paper will be relevant, important, unbiased, sufficiently rigorous, and/or honest. And, more relevantly to academics, it doesn’t mean that it will bring about more citations than other non-peer-reviewed publications.

This latter fact about citations is, of course, a purely internal affair which probably won’t concern anyone outside the Academy. That’s primarily because it seems to be more about academic careers than about quality, rigour, relevance, importance, bias… or, indeed, anything else.

Another thing to note here is how arbitrary the whole peer-review process is… or, at the least, how arbitrary it can be.

Take the example of a change of a single reviewer employed by an academic journal and the fact this change can have a large impact of the results of the journal’s overall peer-reviews. Thus, in crude terms, a simple change in reviewers (even the arrival of a single new reviewer) can result in a dramatic change to what’s deemed to be publishable by that journal.

On a related point, any heterogeneity among referees may — and often does — lead to the basic arbitrariness of the entire peer-review process.

More importantly, what about the outright fraud, “post-truth” politics (or “lying for Justice”) and/or “misinformation” that’s been discovered in many peer-reviewed papers?

Take just one case, as highlighted in ‘Researcher at the center of an epic fraud remains an enigma to those who exposed him’.

The following passage (from this article) shows how deeply incestuous and self-protecting academia can often be:

“Sato’s fraud was one of the biggest in scientific history. The impact of his fabricated reports — many of them on how to reduce the risk of bone fractures — rippled far and wide. Meta-analyses that included his trials came to the wrong conclusion; professional societies based medical guidelines on his papers.”

What’s more:

“The 12 trials Sato published in high-impact journals have been widely cited. Many were included in meta-analyses, sometimes changing the outcomes, or were translated into treatment guidelines. Other researchers used Sato’s fake data as part of the rationale for launching new clinical studies.”

Yet this is an example from medical science and scientific technology (or applied science) — where standards are usually far more rigorous than in other academic disciplines!

One can imagine that, for example, political, sociological and other journals in the humanities are bound to have involved cases which are far worse — and far more frequent — than the Sato story. The problem is, however, unlike details on bone factures, unhappy patients, etc., it’s hard to uncover academic deceit when it comes to such journals. One main reason for that is that hardly any outsiders (or critics) read this stuff. This means that — at least sometimes — we essentially have various extremely secure academic fiefdoms.

So it’s no surprise that we also have the studies featured in this article: ‘Secretive and Subjective, Peer Review Proves Resistant to Study’. These particular studies showed that that there is no “direct evidence” that peer reviews actually improves the quality of published papers…

Sure!

And no doubt there are other peer-reviewed studies or papers which show the exact opposite… Yet that, in a strong way, demonstrates the point.

Because if all these problems, what’s been called “invalid research” has occurred many times — at least according to the academics who’ve looked into these matters.

In terms of problems that people outside the Academy may be concerned with, academics have also noted that the peer-review process can — and often does — lead to political, philosophical, scientific, etc. stifling conformity and uniformity.

Conformity and Uniformity in Academia

In simple terms and depending on the journal, controversial papers are often rejected not for their lack of quality or rigour, or because of clear bias, etc., but because they don’t meet the journal’s often implicit — though sometimes explicit! — standards of political, philosophical or scientific uniformity and conformity. (Not that reviewers will openly and honestly see political, etc. conformity and uniformity as their goals.)

And one consequence of such academic uniformity and conformity is that many of the postgraduates and academics who submit papers to these journals pander to the political, philosophical or scientific biases and “interests” of their academic editors and reviewers…

Indeed that’s obviously the case!

It’s the case because academics and postgraduates wouldn’t have submitted their papers to these particular journals at all if they weren’t aware of such biases and interests.

All the above, then, involves the issue of just how conformist, uniform and/or even obsequious a submitter wants to be in order to get published and — in the future — gain academic tenure. This also means that those who offer controversial or “radical” views may not — or simply will not — get a fair hearing… Unless, that is, the journal is self-consciously radical and/or controversial in nature! But that may — or will — only mean that such a journal is controversial and radical in only very particular political, philosophical or scientific directions… and not in others. So it also needs to be noted that being (self-styled or supposedly) radical, controversial or iconoclastic can also effectively mean that one is uniform and conformist in a radical way — at least within the these limited domains.

********************************

Note: In relation to the screenshot directly above. It’s worth stating that any “peer-reviewed literature” I could have cited would neither have helped nor hindered the arguments I had previously put. That’s because my points didn’t even involve any factual claims or data. Instead, I was simply offering some arguments and analysing various concepts and assumptions. Thus, asking for peer-reviewed back-up in this instance was like asking a pure mathematician to cite peer-reviewed papers on ontology or even on gardening.