The late and great Richard Feynman once famously declared: “Snow is white.” Feynman also quipped that “drinking Earl Grey tea is like making love to a beautiful woman”. Now all that is precisely why The Dick was both a great and a late man.

Why do so many of Richard Feynman’s fans believe that every sentence he ever uttered was profound and deep and worth quoting at every opportunity? In addition, why do so many of Feynman’s words end up in memes and images, which are then spread around Facebook and Twitter like confetti?

(On the goodreads website, there are 24 pages of quotes from Feynman. Each page has at least 23 different quotes on it.)

It’s worth noting immediately that previously (in response to an earlier essay) I discovered that Feynman’s fans often get very angry when someone points out that his fans get very angry when Feynman is criticised. I also noted that many of the writers who actually got around to mentioning the fact that the hero-worship of Feynman really does exists, then go straight ahead and indulge in a bit (or even a lot) of it themselves. (Perhaps to prove that they aren’t philistines or luddites — see here and here. Note that this isn’t a reference to those negative articles which have been written about Feynman’s private life, behaviour and personality.)

In any case, the hero worship of Feynman is very deep and widespread. Of course very few people would deny that he was a great physicist. (Although non-physicists can only believe that Feynman’s physics is great via what philosophers call testimony.) Yet, ironically, most of the Feynman memes and quotes just mentioned are posted by non-physicists. What’s more, nearly all of them are not actually about physics (or even science as a whole) at all.

(I had a problem finding a single meme or image about Feynman’s work on quantum electrodynamics (specifically, Feynman diagrams) and the path integral formulation, which are, after all, what made Feynman famous within physics. Of course this isn’t to deny that he did much other important work too. And perhaps it’s difficult to create a sexy meme about QED, etc.)

It can be argued that Feynman’s fame (at least as it manifests itself outside of physics and physicists) often simply boils down to the fact that he was, well, cool and/or hip. Or, more correctly, it boils down to the fact that Feynman is deemed by many of his fans (often self-described nerds and geeks) to be cool and/or hip. So why was Feynman cool and hip? It seems that Feynman was cool and hip because he played the bongos, “liked a laugh”, was a womaniser, and even had a somewhat quirky face and way of dressing (see here and here).

Thus, Feynman’s image alone (as with many of the fans of James Dean, Che Gevara, Malcolm X, Marlon Brando, Sid Vicious, Kurt Kobain, etc.) is a strong part of the appeal.

Specifically on the endless mentions of Feynman’s bongo-playing. (There are over 7 pages of Google links about Feynman and his penchant for bongos.) The television series The Big Bang Theory accurately summed this up when one of its main characters, Sheldon Cooper (one of the nerds I just mentioned), often emulated Feynman (i.e., in more than one episode) by playing the bongos.

So what about other famous physicists?

The Wise Words of Other Famous Physicists

Why do far too many people (at least those who admire physicists) simply assume that famous physicists (i.e., not any unknown ones) will have insightful things to say on almost (or literally) all other subjects? (I have in mind Michio Kaku, Brian Cox, etc., but especially the highly self-conscious performer Neil deGrasse Tyson.)

I first noted this with Albert Einstein.

Einstein’s non-scientific words are quoted left, right and centre. Yet much of what he said on politics, religion and God is fairly standard stuff. And even when true or fairly insightful, his words would probably have been ignored if said by a layperson or even by an unknown physicist.

Thus, we give the superstars of physics (if not physicists generally) leeway to comment on all sorts of stuff that’s a million miles away from physics. (This is a little like asking pop stars or actors to offer their profound insights on politics.) It’s also a case of a positive ad hominem in that the aforementioned bigged-up men or women are automatically deemed to be saying insightful things simply because they are famous actors, pop stars… or physicists.

In terms of theoretical physicists, I believe that this is primarily because they’re seen as being the “brainiest” of all people — perhaps just behind brain surgeons. (Are brain surgeons “brainy” simply because they carry out surgery on the brain?) Sure, many of them are indeed brainy and even highly imaginative. Yet, again, why does that give them a special insight into Donald Trump, Jeremy Corbyn or “the meaning of life”?

So do economists, psychologists, social scientists, etc. also have some insightful and deep angles on quantum mechanics, string theory or wormholes? It can be accepted that such people could do. However, there’s no reason to simply assume that they do.

The English physicist Stephen Hawking (1942–2018) was a good example of all this.

Hawking talked about politics (see here), religion and, of course, God (see here).

More specifically, Hawking commented on, and was extensively quoted commenting upon, the Iraq War, euthanasia, women in science, Brexit, nuclear weapons, animal testing, Donald Trump, the NHS, the Labour Party, etc. However, as far as I know, none of these comments appeared in his actual books or publications. Thus, if Hawking was asked a question on any given x, then of course he had the right to answer it and offer his view.

So all this is very different from a physicist superstar (such as Michio Kaku, Neil DeGrasse Tyson and, well, Richard Feynman) discussing Black Lives Matter or tax policy in his actual books or articles. In other words, Hawking and others can’t help but answer the questions they’re asked by journalists and others. And there’s no reason that they shouldn’t answer them. After all, physicists are voters, members of society, human beings, etc.

So shouldn’t we expect a little more modesty from such superstar physicists?

That said, since literally millions of people are buying their books, and these books tend to stray way beyond physics, astrophysics and cosmology, then why should such physics superstars stop doing what they do? That is, these theoretical physicists firstly created a niche in (obviously) theoretical physics, etc., and then they branched out… And the more they wrote and got published, the farther and farther out they branched.

Now it must be said that this branching out isn’t always unsuccessful. Indeed sometimes it may even be insightful. However, why do so many of the fans of these physics superstars simply assume that all the examples of this branching out will be interesting, let alone insightful or profound?

Part Two: The Quotes

It can happily be conceded that Feynman might have had extremely insightful things to say about sexual intercourse or Richard Nixon (see later section). However, why should his fans (or anyone else for that matter) simply assume that he did so? What is it about famous theoretical physicists that gives them an insight into tax policy or “the meaning of life”?

It must also be said here that I too can appreciate at least some of Feynman’s words on subjects which have nothing (directly or even indirectly) to do with physics.

Take this (possibly) unanswerable (if ironic) question asked by Feynman. He recalled:

“You know, the most amazing thing happened to me tonight. I saw a car with the license plate ARW 357. Can you imagine? Of all the millions of license plates in the state, what was the chance that I would see that particular one tonight? Amazing!”

This passage can be reformulated as a simple question:

Of all the millions of license plates in the state, why did I see that particular one tonight?

Yet it’s not at all weird that Feynman should have seen that particular number plate. He had to see one number plate when he glanced at that particular time. So whichever numberplate he saw, the same astonished question could have been asked about it.

So, to admittedly stretch things a little, perhaps Feynman’s ironic question is similar to the following non-ironic question:

Why are the laws of physics and the constants of nature the way they are and why do they have the particular values that they have?

Yet perhaps there’s no deep answer — other than mundane facts about probabilities, etc. — to Feynman’s own question as to why he should have seen that particular number plate.

Basically, then, what if these deep questions don’t have answers (or solutions)? Moreover, what if these supposedly profound questions are suspect or bogus in some way? Despite stating that, even if a question may not have an answer, reasons or explanations will still need to be given as to why that’s the case.

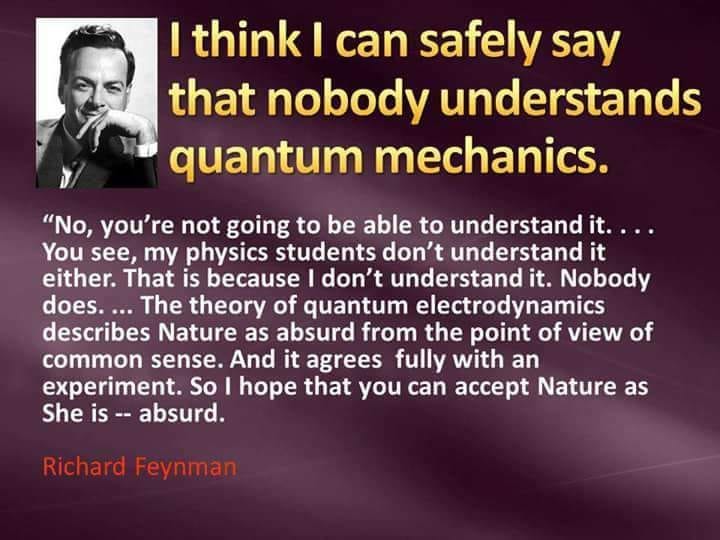

No One Understands Quantum Mechanics

There’s only a single well-known quote from Richard Feynman which I’ll spend a little time on. However, I have no idea where this quote comes from. That’s because, like so many other people, I’m simply quoting the quote. So here goes:

“I think I can safely say that no one understands quantum mechanics.”

To be honest, I find Feynman’s remark to be almost purely rhetorical. After all, it’s fairly well-known that Feynman didn’t have too much time for the interpretations of quantum mechanics, let alone for the philosophy of quantum mechanics. In other words, Feynman knew all of the relevant maths. “The trouble was”, as science writer Philip Ball put it, “that’s all he could do”.

The physicist Christopher Fuchs (also quoted by Philip Ball) expressed the problem with quantum mechanics in terms of “all the posturing and grimacing over [its] paradoxes and mysteries”. Indeed, for many laypersons especially, that posturing and grimacing seems to have become the very essence of quantum mechanics. And perhaps this is even the case for some physicists too…

And from that quantum weirdness there follows the no-one-understands-quantum-mechanics refrain.

So Ball picks up on the bizarre nature of Feynman’s statement when he says that “[a]t that point, no one alive knew more than Richard Feynman about quantum mechanics”. He concluded: “What hope is there, then, for the rest of us?”

On the other hand, it’s easy to agree with Feynman. So it’s not a surprise that Ball says that “[s]ome scientists feel the same way today”. Many scientists, in the words (quoted by Ball) of the physicist David Mermin, also say “shut up and calculate”.

Now for some more Feynman quotes which aren’t technical or even about physics.

Ten More of Feynman’s Oft-Quoted Words

(1)

“Nobody ever figures out what life is all about, and it doesn’t matter. Explore the world. Nearly everything is really interesting if you go into it deeply enough.”

That’s okay advice. However, it’s still pretty banal. Indeed it could have been said by very many science teachers and physicists — and probably has been. (Perhaps some of Feynman’s fans wouldn’t deny that.) And it also assumes that “life” (whatever that is) is “about” something, even if we can’t discover what it is about. That said, Feynman did concede that it “doesn’t matter”. In addition, I don’t believe that many (or even any) people are psychologically constituted to find “nearly everything” interesting.

(2)

“Religion is a culture of faith; science is a culture of doubt.”

That has been said (if in different ways) by countless scientists (countless times) over the centuries (though especially since the 19th century).

(3)

“I would rather have questions that can’t be answered than answers that can’t be questioned.”

Ditto.

(4)

“If you thought that science was certain — well, that is just an error on your part.”

Ditto.

(5)

“It doesn’t make a difference how beautiful your guess is. It doesn’t make a difference how smart you are, who made the guess, or what his name is. If it disagrees with experiment, it’s wrong.”

Ditto.

(6)

“I’m smart enough to know that I’m dumb.”

That’s fairly witty. However, it could well be a witty variation on Socrates’ well-known words — “I believe that I know nothing”. It also includes an obvious bit of vanity, which is, nonetheless, hidden underneath the false modesty. That is, Feynman seemed to really be saying this:

I’m so damn clever that I’ve also realised that I’m not omniscient.

So now read these words from Peter Woit:

“I avidly read the Feynman anecdote books when they came out and was suitably entertained, but I also found them a bit disturbing. Too many of the anecdotes seemed to revolve around Feynman showing how much smarter he was than someone else.”

(7)

“Physics is to math what sex is to masturbation.”

It’s probably quotes like this which appeal to many of the non-physicist fans of Feynman. It’s witty and sexy, sure. However, if taken literally, then its meaning — or even truth — would quickly evaporate.

(8)

“Philosophy of science is about as useful to scientists as ornithology is to birds.”

Physicists love quoting this. And those who dislike philosophy can’t resist quoting it either.

There are so many problems with that — yes, witty — statement that it would take an entire article to tackle it. (Indeed I have done so.) But, then again, I’m probably as biased on this subject as Feynman was.

(9)

“The highest forms of understanding we can achieve are laughter and human compassion.”

I have absolutely no idea what that means. Even in purely grammatical terms, it’s almost meaningless. So perhaps it’s poetry. Perhaps only someone as wise as Feynman (or one of his fans) could know what it means.

(10)

“Physics isn’t the most important thing. Love is.”

Pass the sick bag.

And so on… ad infinitum.

*************************

Note:

It’s worth saying that some physicists and commentators have said that Richard Feynman’s contribution to physics has been overexaggerated. (Indeed some have gone even further than that.) Personally, I’m not one of these people. However, that may simply be because I’m not a physicist myself. Thus, I’m not really qualified to say either way. That said, my not being qualified to comment on Feynman’s actual physics (at least not with any original or insightful words) puts me in exactly the same position as many — or even most — of his fans.

*) See my ‘Why Richard Feynman (the Superstar Physicist) Hated Philosophy and Philosophers’.