Philosopher Donald Davidson once wrote that conceptual schemes are deemed to be “ways of organizing experience”; as well as “systems of categories that give form to the data of sensation”. What’s more, “they are points of view from which individuals, cultures, or periods survey the passing scene”. From this line of reasoning (which Davidson himself rejected), we pass on to such things as “linguistic relativity” (or the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis) and, perhaps (!), Kuhnian paradigms and Wittgensteinian language games.

Let’s start off with Donald Davidson’s take on what conceptual schemes are supposed to be. Davidson wrote the following:

“Conceptual schemes, we are told, are ways of organizing experience; they are systems of categories that give form to the data of sensation; they are points of view from which individuals, cultures, or periods survey the passing scene.”

This passage can be found in Davidson’s paper ‘On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme’. That paper at least partly inspired the following essay.

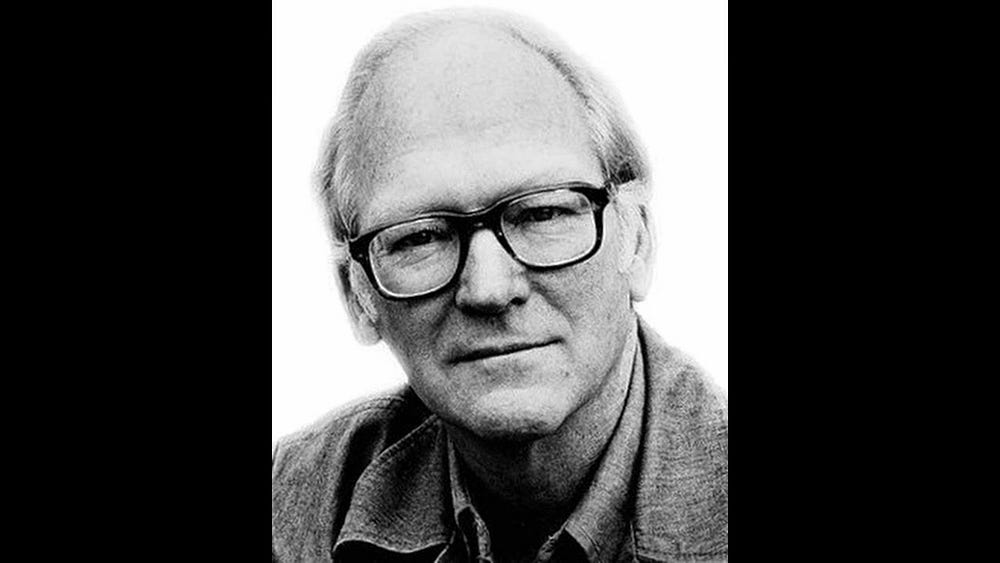

Davidson (who died in 2003) was primarily responding to the thesis that different “individuals, cultures, or periods” have different conceptual schemes. What’s more, these schemes are said to be at odds — or even in conflict — with each other.

The position that Davidson was at least partially arguing against is what’s called the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. (It’s worth stressing here that Davidson certainly wasn’t doing anthropology, history or political commentary.) The following is one definition of that hypothesis:

“The simplest Sapir-Whorf hypothesis definition is a theory of language that suggests that the language a person speaks determines or influences how they think. According to Sapir-Whorf, a person’s native language has a major impact on how they see the world.”

This means that Davidson’s clause “we are told” (in the opening passage) gave his game away…

That game being his rejection of the very idea of a conceptual scheme.

Davidson’s position was that there is only one conceptual scheme.

This basically means that, in a strong sense, there are no conceptual schemes at all… Or at least there are no conceptual schemes as such things came to seen by certain philosophers — and, indeed, by various social scientists.

Crudely speaking, this particular take on conceptual schemes (i.e., the one which Davidson had a problem with) partially mirrors Thomas Kuhn’s notion of a scientific paradigm and Ludwig Wittgenstein’s notion of a language game. However, if anything, a conceptual scheme has been deemed to be much deeper and far broader than a (scientific or otherwise) paradigm or a language game. Indeed it can even be argued that paradigms and language games must themselves belong to (or be embedded within) broader conceptual schemes.

All that said, I won’t be commenting on Davidson’s paper or even on anything specific within it. The main reason for that is that Davidson had a particularly epistemological take on this issue. (See the note at the end of this essay.)

We can start here with the American philosopher Thomas Nagel.

Nagel advanced the view that we can divorce ourselves from our conceptual schemes and even from our concepts. (It must be stressed here that the position which Nagel advanced is quite unlike Davidson’s.)

Thomas Nagel, Thomson Clarke and Steven Stitch

In his book The Last Word (1997), Thomas Nagel argued that the “obsession with language” and conceptual schemes has “contributed to the devastation of reason”. He went on to argue that if philosophers and laypersons stress the importance of language and conceptual schemes generally (which are, after all, contingent), then they’re in effect stressing the contingencies of psychology and culture too. And it’s this approach, Nagel concluded, which “leads to relativism”.

All this raises the following two questions:

(1) How many (broadly speaking) differences are required to create a separate conceptual scheme?

(2) How many differences are required to make two different conceptual schemes mutually incompatible or even incommensurable?

If a distinction were to be made between two different conceptual schemes, then the boundary between them may well be vague. So how deep must conceptual variance go before something is christened a conceptual scheme? Would it necessarily mean that a new conceptual scheme would — or could — never (metaphorically) look out at other (possibly rival or competing) conceptual schemes in order to judge (or simply evaluate) them?

Clearly, simple differences in beliefs can’t themselves constitute different conceptual schemes. If that were the case, then we’d all belong to different conceptual schemes. In fact each individual would have his or her own conceptual scheme.

So perhaps it’s when concepts and/or beliefs begin to link up together and have mutual implications and entailments that the question of different conceptual schemes arises.

Take the following technical distinction which was made by the American philosopher Steven Stitch (1943-) in his paper ‘The Problem of Cognitive Diversity’. He wrote:

“[T]he Yoruba do not have a distinction corresponding to our distinction between knowledge and (mere) true belief.”

In this essay’s context, this raises the question as to whether or not having (or accepting) the distinction between knowledge and true belief itself entails, implies or generates other concepts which, in turn, partly help form a distinctive conceptual scheme. (Of course we can also ask if this is just a philosophical distinction that not even all members of “our own” culture — whatever we take that to be — share.)

Firstly, a belief in true belief or knowledge isn’t itself really a single belief. It’s a belief made up of other beliefs.

Again, the main question is whether or not we can stand outside our conceptual scheme (or conceptual schemes) and evaluate other conceptual schemes (or other cultures and historical periods).

Perhaps the American philosopher Thompson Clarke (1928–2012), for one, believed that we can. In his paper ‘The Legacy of Scepticism’, he wrote:

“Each concept or the conceptual scheme must be divorceable intact from our practices, from whatever constituted the essential nature of the plain. […] [O]bservers who usually by means of our senses, ascertain, when possible, whether items fulfil the conditions legislated by concepts.”

So did Thompson Clarke himself step outside his own conceptual scheme into other conceptual schemes in order to evaluate them? Alternatively, did he adopt a God’s-eye view (or “view from nowhere”) of what he called “the plain”?

There is a hint in the above passage that Clarke believed that he could become free of both concepts and conceptual schemes when he asked “whether [sensory] items fulfil the conditions legislated by concepts”. Thus, these sensory items (contrary to the note on Davidson at the end of this essay) seem to come first — at least in this instance. In any case, Clarke was certainly committed to the world’s “essential” nature when he wrote about “the essential nature of the plain”.

Some readers may now ask what “truth in all discourses” (if not in all conceptual schemes) actually is. It may also be asked if truth can be external to all conceptual schemes.

Truth in All Conceptual Schemes

What if a member of each conceptual scheme has his/her own version (or versions) of the nature of truth? And what if each member of such conceptual schemes also has his/her own truths?

Wouldn’t this create difficulties in communication… or worse?

That said, if different conceptual schemes can accept or believe (discounting different languages) the same claims (for example, that 2 + 2 = 4 or that Napoleon was an Emperor of France), then why can’t they agree on other more esoteric, recondite or controversial things too? Indeed it could be the case that from the fact that different conceptual schemes accept the non-contentious, then they may then (mutually) accept the contentious too.

Think here of how easy it is to agree on the weather, “established facts”, etc., and yet how hard it sometimes is to agree on politics, morality, art, music, etc.

More particularly, if different conceptual schemes can discuss and even agree on the weather, when Hitler died or what is the largest body in the Solar System, then perhaps they can also discuss and agree upon more contentious issues…

Or are there language games about the weather, historical facts and astronomy too?

Let’s get back to truths (or indeed facts) which are external to conceptual schemes.

If a conceptual scheme is chosen (rather than, say, born into) by an adult individual, then it must be so for reasons which are external to that conceptual scheme. Similarly, an individual may reject his — or a — conceptual scheme for reasons external to that conceptual scheme.

Now let’s (perhaps) be a little naïve here. Take these three simple logical examples and statements:

(1) A = A (in all conceptual schemes)

(2) A = B = C ⊃ A = C (in all conceptual schemes)

(3) P ⊃ Q

P

∴ Q

(in all conceptual schemes)

Similarly, does the schema (if not the actual content)

The sentence “Snow is white” is true if and only if snow is white.

hold in only one conceptual scheme?

More factually and empirically.

If everyone — or almost everyone — believes that Napoleon was an Emperor of France, then they must also believe many other things which can be — or are — derived from (or dependent upon) such a belief. For example, that France exists. That France did indeed have an Emperor. That there was a time when France didn’t have an Emperor. (This last belief isn’t logically derived from the initial belief.) And if we all believe that Napoleon was an Emperor of France, then surely we may then also mutually believe that there were specific reasons as to why he became such a leader. So perhaps there can be agreement on those reasons too.

Those simple bits of logic above were intended to show that the contentious can be derived from the uncontentious. This itself may shows that if conceptual schemes share the uncontentious, then there’s nothing to stop them — in principle — from sharing the contentious too.

All this, in turn, casts doubt on the incommensurability (see also Kuhnian incommensurability) and untranslatability theses when applied — specifically — to conceptual schemes. And, if that’s the case, then perhaps the idea of different — or even rival — conceptual schemes is flawed.

That said, none of the above need imply that there’s a possibility of escaping from all conceptual schemes into Thomas Nagel’s or Thomson Clarke’s wilderness of Nowhere — the view from where we can see the world As It Truly Is

*********************

Note: Donald Davidson’s Own Take

It’s worth stressing here that Donald Davidson’s own position (which is quite unlike anything advanced in the essay above) was grounded on purely epistemological and philosophy-of-mind considerations, not on denying (or, for that matter, stressing) anthropological, historical and/or cultural differences.

That grounding can be found in the following passage (from the paper ‘A Coherence Theory of Truth and Knowledge’), in which Davidson wrote:

“The relation between a sensation and a belief cannot be logical. Since sensations are not beliefs or other propositional attitudes. What then is the relation? The answer is, I think, obvious: the relation is causal. Sensations cause some beliefs and in this sense are the basis or ground of those beliefs. But a causal explanation of belief does not show how or why the belief is justified.”

Another passage (from the same paper) is even more apposite in this context. Davidson continued:

“Accordingly, I suggest that we give up the idea that meaning or knowledge is grounded on something that counts as an ultimate source of evidence. No doubt meaning and knowledge depend on experience, and experience ultimately on sensation. But this is the ‘depend’ of causality, not of evidence or justification.”

Basically, then, if this distinction between (as it were) pure and given “experiences” (or “sensations”) and later beliefs is rejected (as Davidson did), then the idea of conceptual schemes being free to (metaphorically) make sense (in multiple different ways) of those pure and given sensations is much harder to defend.

No comments:

Post a Comment