This essay is on the importance and relevance of definitions when it comes to debates about consciousness and intelligence. (As mainly found in Anil Seth’s book Being You.) More specifically, it focuses on definitions when it comes to the relation of intelligence to consciousness, and vice versa.

Philosophers and laypeople can use the same terms in very different ways. What’s more, not all people define or explain their terms in the first place. Nor do they always explain how and why such terms almost entirely flow from their very particular philosophies.

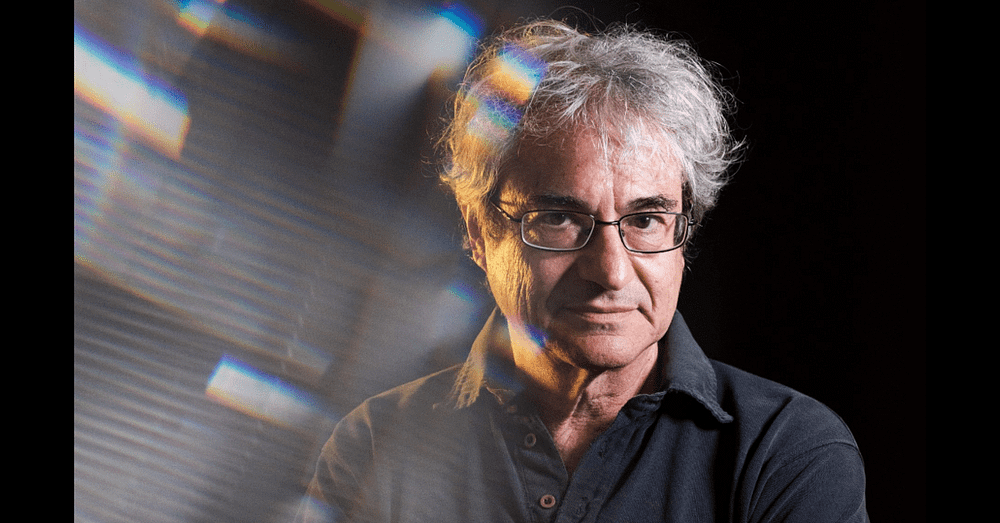

The British neuroscientist Anil Seth (implicitly) recognises the importance of definitions when he tells us that “[f]or me, there are no knock-down arguments”. That is, they’re no knock-down arguments when it comes to some of the issues around consciousness which he discusses (i.e., in his book Being You: A New Science of Consciousness).

Is that primarily because it partly — or even mainly — depends on definitions?

Moreover, just as definitions are important in this debate, so too is the (to quote Seth again) “theory of consciousness you subscribe to”.

Thus, according to a certain theory of consciousness, certain things will account for what would makes an entity conscious and/or intelligent. With another theory, (completely?) different things will account for what makes an entity conscious and/or intelligent.

It’s (Nearly) All About Definitions

Anil Seth lays his own cards on the table when he states the following:

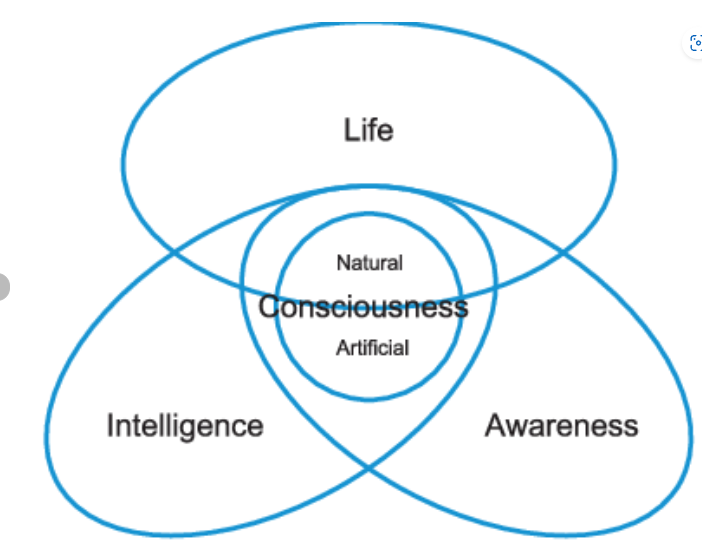

“[C]onsciousness is not determined by intelligence, and intelligence can exist without consciousness.”

Of course, some theorists and philosophers believe that (high levels of?) intelligence must always come along with a degree of consciousness. Others simply invert this binary relation and argue that consciousness is intrinsically linked to intelligence…

Anil Seth rejects both these positions.

Put simply, Seth argues that computers and robots can be (very) intelligent without ever instantiating consciousness. And ants, viruses, etc. may be conscious without also being intelligent…

But hang on a minute!

All this depends on how we define the words “intelligence” and “consciousness” in the first place!

After all, on many definitions, intelligence does indeed come along with consciousness. And, on other definitions, consciousness doesn’t (necessarily?) come along with intelligence.

This means that in this debate at least, many people may well be talking passed each other.

More concretely, the importance of definitions is — again, implicitly — recognised by Seth when he tells us that

“it could be that all conscious entities are at least a little bit intelligent, if intelligence is defined sufficiently broadly” .

Yet this isn’t just a problem created by the broad definitions of the words “intelligence” and “consciousness” (or “conscious”). It’s also about the different definitions of these two words. That said, some differences between these words may themselves be a result of their very-broad definitions.

In addition, if an entity displays “at least a little bit [of] intelligence”, then some may well argue that it must also be displaying at least a little bit of consciousness.

So, here again, it not only depends on definitions: it also depends on how different words (in this case, “intelligence” and “consciousness”) depend on each other for their meaning. [See note 1 on Ferdinand Saussure.]

David Chalmers on Stipulation

The Australian philosopher David Chalmers often stresses the importance of what he calls “stipulation” when it comes to philosophically-loaded terms. His basic point is that if we stipulate what we mean by a particular word, then the answers to any questions we have about facts, data, what x is, etc. must — at least partly — follow from such prior stipulations.

Of course, there is a problem with over-stressing the importance of stipulation. Indeed, Chalmers himself sums up this problem with a joke. He wrote:

“One might as well define ‘world peace’ as ‘a ham sandwich.’ Achieving world peace becomes much easier, but it is a hollow achievement.”

Clearly, even when someone argues that stipulation is important, he or she won’t also accept that we can define the words “world peace” as “a ham sandwich”. In turn, some philosophers and laypersons will feel just as strongly about claiming that, say, a computer virus is alive (see here) or that bacteria learn (see here).

As it is, Chalmers only applies his joke to a single case: consciousness.

So perhaps it can be applied to other cases too.

The History of the Word “Consciousness”

As a result of all the problems highlighted above, perhaps it would be wise to adopt a deflationary — as well as a stipulational (as with Chalmers)— view of the word “consciousness’”. That’s what the philosopher Kathleen Wilkes did when she wrote that

“perhaps ‘consciousness’ is best seen as a sort of dummy-term like ‘thing’, useful for the flexibility that is assured by its lack of specific content”.

Yet writing at the end of the 19th century, the psychologists James Ward and Alexander Bain took a strong line against the ostensible liberalism (or pluralism) toward the word “consciousness”. They argued that it’s precisely because that word is a dummy-term (as Wilkes put it) that it traps us in the mud. They wrote:

“‘Consciousness’ is the vaguest, most protean, and most treacherous of psychological terms.”

With strong words like that, one can see how it didn’t take long for behaviourism to take up its hegemonic position in psychology and philosophy in the 1920s and beyond.

Conclusion

The problem is that if people engaged in an exchange are using the same term in very different ways, then we can hardly say that there’s any debate occurring in the first place. What’s more, this situation is confounded by the fact that the debaters assume — or simply believe — that his/her opponent is using the same word (or term) in the same way. That’s the case even when it’s clear to some on the outside that this isn’t happening. Thus, again, how can we even say that there is a debate (or dialogue) going on here if the debaters are talking about different things — even when they’re using exactly the same words (or terms)?

More relevantly to this essay, when people use, mention and share the words “consciousness”, “intelligence”, etc., and mean very different things by them, then that situation is far worse than one in which a debater simply makes a statement which is followed by a largely unrelated counter-statement (though not a counter-argument) from his fellow debater. In this former case, there’s the seeming situation that the debaters are talking about the same thing. Yet if they’re using their primary terms in very different ways, and those terms are born of very different philosophies, then that’s even worse than a simple shouting match between two rival debaters. At least in this latter case the debaters are talking about the same thing — even if they strongly disagree with each other.

Finally, it’s of course the case that any given philosopher or layperson might well have defined his terms elsewhere — even in great detail. Moreover, you can’t expect a philosopher or layperson to define his (disputed) terms every time he uses them. All that said, even if he has defined his terms elsewhere, the chances that the reader (or fellow debater) has read those definitions may well be — and usually are — very slim indeed.

Note

(1) Take Ferdinand de Saussure’s stress on the (rather obvious?) relation of words to other words, the nature of linguistic “systems”, and the “[system of] differences” set up between words within such systems.

More relevantly, the words “intelligence” and “consciousness” not only need to be defined: they can also be seen to be involved in various negative and positive “binary oppositions”.