The main character in The Matrix (Neo) experienced a reality which was entirely an illusion. Yet, on David Chalmers’ take, his reality+ idea is mainly about what does — and what will — happen when individuals, groups and entire societies consciously (or willingly) create virtual realities. Thus, in that strong sense, Chalmers isn’t offering us his own 2023 (or 2022) version of The Matrix and other sceptical scenarios. Instead, his reality+ idea is largely about “extending our sense of the real”.

Philosopher David Chalmers’ own take on virtual reality isn’t like The Matrix scenario or René Descartes’ evil demon thought experiment. Indeed, his own term “reality+” actually captures that difference.

Basically, in his book Reality+: Virtual Worlds and the Problems of Philosophy, Chalmers discusses the many implications of our living with (as well as living in) nonvirtual worlds… + virtual worlds.

The Matrix

As many commentators have already pointed out, The Matrix can be viewed as a new-fangled take on Descartes’ evil demon story (or thought experiment). Of course, this isn’t to say that The Matrix is identical to Descartes’ evil demon — just with added contemporary knobs on.

It’s also worth saying that The Matrix owes just as much to the many and various brain-in-a-vat scenarios which have been offered to the public over the last five decades.

For example, way back in 1968 (some 31 years before The Matrix), the philosophers James Cornman and Keith Lehrer suggested that what they called the “braino machine” could do the following things:

“[It could] operate by influencing the brain of a subject who wears a special cap, called a ‘braino cap.’ When the braino cap is placed on a subject’s head, the operator of the braino can affect his brain so as to produce any hallucination in the subject that the operator wishes. The braino is a hallucination-producing machine. The hallucinations produced by it may be as complete, systematic, and coherent as the operator of the braino desires to make them.”

The scenario above is now very familiar to many people.

Ironically, the philosopher Hilary Putnam argued — over many years — that

“the supposition that we are actually brains in a vat, although it violates no physical law, and is perfectly consistent with everything we have experienced, cannot possibly be true”.

Why is that?

Well, “[i]t cannot possibly be true, because it is, in a certain way, self-refuting”.

Of course, there’s a vast literature on this brain-in-a-vat story which can’t be tackled in this essay! (See here.)

So if we return to Descartes’ evil demon.

David Chalmers himself writes:

“I first argue that we can’t know we’re not in a simulation like the Matrix. This is a modern-day version of Rene Descartes’s idea that we might be in the grip of an evil demon producing sensations of an external world.”

More relevantly:

“We can never prove we’re not in a computer simulation because any evidence of ordinary reality could be simulated.”

So The Matrix is — at least partly — about what philosophers call global scepticism…

However. The Matrix story may not actually be an artistic take on global scepticism at all.

That’s because global scepticism has it that we can’t know anything at all. The Matrix, on the other hand, is only about our perceptions of the world and the possibility that we can’t know if they’re all illusions. This may mean that Matrix-scepticism is only global when it comes to our perceptions. Indeed, this may actually make it a case of local scepticism…

Yet surely scepticism about all our perceptions (if broadly construed) will pass over to scepticism about… everything.

After all, it may not only be that what we see, hear, smell and touch is illusionary: what we think and believe may be illusionary too. Indeed, what we perceive has often been closely tied — by many philosophers and scientists — to what we both believe and think. Thus, on this picture, perceptions are parts of a package deal which also includes thoughts, beliefs and memories. [See note 1.)

Of course, not all viewers of The Matrix need to be aware of all this philosophical stuff. (I suspect that most viewers haven’t been.) That is, they may not have even thought about scepticism in this explicitly philosophical sense. That said, perhaps this simply means that most viewers have never used the words “scepticism”, “global scepticism”, “evil demon”, etc. when thinking (or talking) about The Matrix…

But who cares about that (almost) irrelevant fact about word usage?

So The Matrix can be used for one’s own ends, as indeed David Chalmers and many others have done over the last 24 years. (The Matrix was released in 1999.)

Now - what is real?

Simulations are Real Fakes

David Chalmers writes:

“Simulations are not illusions. Virtual worlds are real. Virtual objects are real.”

In fact, the rebel leader Morpheus (played by Laurence Fishburne) makes these points in The Matrix:

“How do you define ‘real’? If you’re talking about what you can feel, what you can smell, what you can taste and see, then ‘real’ is simply electrical signals interpreted by your brain.”

In a strong and very simple sense, a visual simulation, and even an entire package of simulations occurring together to create a virtual reality, can’t be an illusion in and of itself. After all, what you see, hear, touch, etc. is still real.

This means that it must be what people make of a simulation which may (or which will) involve illusion.

For example, if you believe that the unicorn in front of you is real and not a simulation (or an hallucination), then you’ve swallowed that particular illusion. On the other hand, since most people know when they’re witnessing a virtual reality, then the word “illusion” simply isn’t appropriate.

What’s more, such supposed illusions even have (or simply may have) a physical basis in that the software for the images is instantiated in physical hardware. In addition, whatever is going on in the human sensory system and brain when such things are stimulated (i.e., not simulated) must also be physical.

In any case, David Chalmers extrapolates from these points about (as it were) real fakes by stating the following:

“The central thesis of the book is virtual reality is genuine reality. This applies both to full-scale simulated universes, such as the Matrix, and to the more realistic virtual worlds of the coming metaverse.”

Chalmers adds:

“But I argue that even if we’re in a simulation like the Matrix, the world around us is perfectly real. There are still tables and chairs, planets and people.”

Indeed, on a more psychological, sociological and even political level, the following passage expresses how Chalmers sees things when they’re placed in a much broader context:

“These worlds needn’t be illusions, hallucinations, or fictions. Our time in them needn’t be escapism. People already lead complex and meaningful lives in virtual worlds such as Second Life, and VR will make this commonplace.”

That quoted, these wider psychological, sociological and political contexts won’t be tackled here. (Chalmers himself does tackle them in his book Reality+: Virtual Worlds and the Problems of Philosophy.)

Proof?

Let me reuse a passage from David Chalmers which was quoted at the beginning of this essay:

“We can never prove we’re not in a computer simulation because any evidence of ordinary reality could be simulated.”

Some readers may wonder how we should take the word “prove” here.

As ever, most times the word “prove” (or “proof”) is used in its loose — or everyday — sense. And, at other times, it’s used in its strict mathematical and logical senses. (Perhaps most uses of the word “prove” fall somewhere in between these demarcations.)

In any case, it can be doubted that there could ever be a strict proof that a Matrix-like simulation… is a simulation. (In accordance with the last section, this is better than saying that the simulation is “unreal”.)

For example and crudely, if I were to discover a hidden Wi-Fi connection which connected a computer to my brain, then that still wouldn’t be a proof that my perceptions are simulations. This would simply be (empirical) evidence (i.e., not proof) that my perceptions may be (or even are) simulations.

[The Matrix scenario is, of course, much more complicated than my own simply story.]

So finding evidence of computer-to-brain Wi-Fi connection still wouldn’t be a philosophical or logical proof of my living in a simulation. That’s mainly because my (seemingly) evidential and empirical discoveries could also be simulations. Thus, I could be experiencing a simulation which seems to show me that all my experiences are simulations.

Put simply, then, whatever evidence (at least sensory or observational evidence) I find could also be a simulation. Indeed, we can ratchet this sceptical scenario up and say that sentient machines (or evil demons) are making me believe and think that I’m finding evidence that I’m being stimulated to believe certain things about both myself and my environment. What’s more, my discovering that that my very thought (i.e., that all my perceptions are simulations) could itself be the result of a simulation or a manipulation of my brain. And so on and so on.

Illusions All the Way Down?

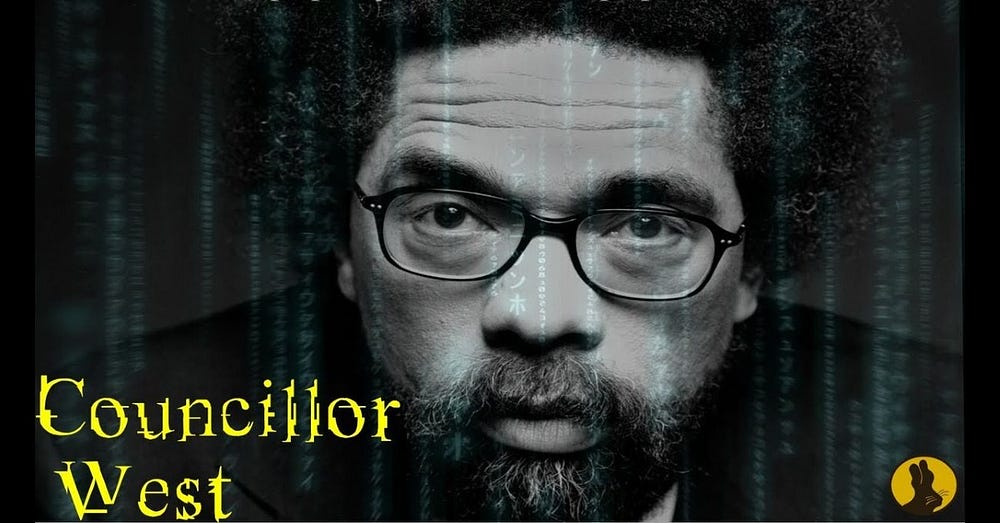

Professor Cornel West (who played Councillor West of Zion in The Matrix Reloaded) expressed the overall gist of The Matrix — and perhaps life generally! — in this way:

“It’s illusions all the way down.”

There’s a problem with West’s claim that it’s illusions all the way down.

This claim is like saying that everyone in a class, or even in the entire world, is brave. Thus, if everyone is brave, then no one is brave. Similarly, if everything is an illusion, then there’s nothing to compare any single illusion to — except other illusions. That is, in The Matrix — and in other (globally) sceptical scenarios — there are no non-illusions to compare each and every illusion to. So if literally everything (we’d need to state what’s meant by “everything”) is an illusion, then nothing is an illusion. [See note 2.]

All this is a similar to Ludwig Wittgenstein’s doubts about doubt. Or, more accurately, it can be compared to Wittgenstein’s doubts about global doubt.

In simple terms, Wittgenstein argued that if literally everything is doubted, then nothing can be doubted. He wrote:

“The questions that we raise and our doubts depend on the fact that some propositions are exempt from doubt, are as it were like hinges on which those [doubts] turn. []

“My life consists in my being content to accept many things.”

To paraphrase Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein argued that the very act of doubting anything requires us to leave at least some things free from doubt. Indeed, if this suspension-of-doubt isn’t carried out, then the language game of doubting can’t even begin. (See Wittgenstein’s On Certainty.)

In any case, the it’s-illusions-all-the-way-down hypothesis (or possibility) is actually written into this example of global scepticism. That’s primarily because there’s no way of finding out if it is actually illusions all the way down. Again, the possibility (or reality) of never being able to find out that it’s illusions all the way down is deliberately — and obviously — written into this sceptical story…

To repeat. If everything is an illusion, then we have no purchase on that very fact (or possibility). That’s because up until realising that everything is an illusion (that’s if this realisation doesn’t itself contain a contradiction), everything we’d previously experienced (or even believed we knew) had been an illusion too.

Of course, if a globally-sceptical scenario is deliberately designed to preclude all possibilities of discovering that “reality is an illusion”, then that doesn’t also mean that it can’t be discovered that the sceptical scenario itself is (as it were) an illusion. It simply means that the sceptical philosopher (or film director/writer) wanted to create a scenario that was without any holes. However, that needn't also mean that his scenario is without holes.

Despite all that, and in the case of The Matrix at least, the main protagonist (Neo, who was played by Keanu Reeves) was offered a red pill — which was, indeed, a way out of the prison of illusions!

However, even in this singular case of escape from the prison of illusions, the red pill had to be offered to Neo by someone else — by the rebel leader Morpheus. Yet when it came to Neo himself, and had he been left entirely to his own (epistemic) devices, then he would (or could) never have discovered that it’s illusions all the way down.

*************************

Notes

(1) It’s worth noting here that all this doesn’t really have anything to do with what’s usually called external world scepticism. This idea is primarily generated by the fact — or claim — that material knowledge can only be attained through our perception of the world. What’s more, our (to use the British Empiricists’ term) sense impressions do not — Bishop Berkeley argued that they cannot — correspond with any physical state of affairs.

(2) “Everything”? “Nothing?” Some philosophers have emphasised the importance of limited — or contextual — quantification. That is, quantification over specific domains. The philosopher and logician Graham Priest, on the other hand, believes that “it’s okay to use a quantifier with the widest possible scope”. That is, it’s fine to quantify over literally everything.

My flickr account and Twitter account.